A Report on the Status of Academic Work Life - CSU-AAUP

advertisement

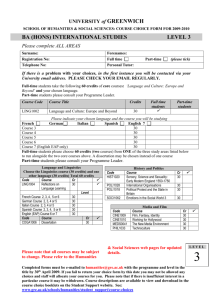

A Report on the Status of Academic Work Life Connecticut State University System Study commissioned by CSU-AAUP Study conducted by the New England Resource Center for Higher Education (NERCHE), University of Massachusetts, Boston. Principal Investigator: Dr. Jay R. Dee EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Prepared by Debra S. Emmelman, Sociology, SCSU On behalf of CSU-AAUP Workload Study Committee: Virginia Metaxas, History, SCSU, Chair, Jason B. Jones, English, CCSU Elena Tapia, English, ECSU Kathryn Wiss, Communications, WCSU March 29, 2011 CSU-AAUP commissioned The New England Resource Center for Higher Education (NERCHE) to conduct a study of academic workload issues to determine the effects of current academic workloads on the ability to provide a high quality of education. Data were collected through surveys and interviews with full-time and part-time faculty members, academic department chairs, search committee chairs, administrators, librarians, coaches/trainers, and counselors. Data were analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively. Faculty survey findings were compared to data from the National Survey of Postsecondary Faculty (NSOPF), collected by the National Center for Education Statistics (U.S. Department of Education). The following are highlights of the findings for all four CSU campuses. Average Faculty Work Weeks were higher than the national average for full-time faculty at all four CSU campuses, especially when faculty members were provided on the survey with a broader range of activities from which to choose rather than forced to choose between the rather ambiguous categories of paid/unpaid. Regarding the latter, the faculty workweek ranged from 53.4 hours per week average at one campus to 55.8 at another campus. The national average is 53.2. Regarding the former, the faculty workweek ranged from 61.01 hours per week average at one campus to 58.15 at another. The national average is 53.2. Although faculty members are considered ten-month employees, their Summer Workload (excluding summer teaching) ranged from six forty-hour workweeks at one campus to four forty-hour workweeks at another. Summer activities included (in order of most time spent) research and other scholarly activity, preparing for classes for the next academic year, administrative responsibilities, unpaid work to academic professional associations and journals in field of discipline, unpaid professional service and outreach activities, advising students within their department or program, supervising students in internships or field placements, and thesis direction. Distribution of annual Faculty Load Credits varied among the campuses, with one campus receiving the highest average instructional load credit of 12.78 and another campus receiving the highest average non-instructional load credit of 3.18. Instructional load credit included courses, labs, supervision of student-teachers, independent studies, thesis supervision, and supplemental credits for labs. Non-instructional load credit included special assignments, administrative duties, reassigned time for curriculum development, reassigned time for research, on-line course development, reassigned time for external grants, and other non-instructional assignments. The following observations were made: Reassigned time for research ranged from 4.2% to 1.4% of all load credits awarded to each of the campuses. At all campuses, the minimum obligations for awarding research reassigned time were exceeded each semester for all campuses. Reassigned time for curriculum development ranged from 10.3% to 4.4% of total load credits awarded at each of the four campuses. The minimum obligations for awarding time were exceeded for every semester studied at all the CSU campuses. Reassigned time for administrative duties ranged from 7.9% to 5.7% of total load credits awarded at each of the four campuses, and reassigned time for special assignments ranged from 4.9% to 0.0% of total load credits awarded at each of the four campuses. Average sabbatical load credits per full-time faculty member per year ranged from .49 to .836 at each of the four campuses. The percentage of part-time faculty instructional load credits exceeded the 2007-11 collective bargaining agreement at all four campuses, ranging from 32.3% to 42.2% at each of the campuses. Based on calculations reported by the four institutions, each campus would be able to award one load credit for every laboratory/studio taught if they were to allocate the following additional increments of load credit: 50.5 additional load credits per year at CCSU 10 additional load credits per year at ECSU 180.5 additional load credits per year at SCSU 20.4 additional load credits per year at WCSU The larger amounts of additional load credits needed at Central and Southern are attributable, in part, to the fact that neither institution fulfilled contractual requirements for providing supplemental lab credit (article 10.6.4). Regarding Pedagogy and Teaching Practices, full-time CSU faculty were more likely than the national average at similar institutions to use a range of pedagogical practices as well as innovate in their courses to improve teaching and learning. However, there was some concern regarding the ability of faculty to continue this trend due to high workload issues. Some of the findings regarding Job Satisfaction suggest concern for faculty morale. In particular, all the campuses reported a higher level of dissatisfaction or disagreement than the national average regarding workload, rewards for good teaching, and institutional support for teaching with technology. In addition, three out of four campuses reported a higher level of dissatisfaction or disagreement than the national average regarding treatment of women faculty; half of the campuses reported a higher level of dissatisfaction or disagreement than the national average regarding treatment of faculty who are members of racial or ethnic minority groups and institutional support for teaching improvement; and one campus reported a higher level of dissatisfaction or disagreement than the national average regarding salary, their job in general at the institution, and the quality of equipment and facilities available for classroom instruction. Some findings regarding the Academic Work Environment indicate that the majority of faculty members express dissatisfaction or disagreement in the following areas: Three out of four campuses show dissatisfaction regarding institutional support for research, creative, and other scholarly activities, availability of childcare, consistency of the institution’s evaluation and reward system with the faculty member’s own scholarly research and teaching interests, the balance of work and personal life that the institution encourages, and rewards for serving the public/community. Two out of four campuses are dissatisfied with the lack of clear criteria for promotion and tenure, and the lack of support for faculty development. One campus out of four is dissatisfied with institutional support for community/public outreach, secretarial and/or professional staff support, incorporation of faculty concerns when making policy, involvement of faculty in campus decision-making. In interviews, faculty members’ primary concerns regarding Teaching Loads and Teaching Effectiveness were that Current teaching loads limit pedagogical innovation and interfere with faculty efforts to promote student learning, Current teaching loads may not allow faculty to remain current within their respective disciplines, and therefore, they may not be able to deliver a state-of-theart curriculum to students, and The faculty load credit system does not appropriately account for faculty workloads associated with teaching labs or studios. Study participants indicated that Research Expectations were increasing, and that consequently, there is some degree of confusion and uncertainty regarding Promotion and Tenure standards. Specifically, participants were uncertain about the forms and types of research deemed acceptable by various evaluators, the extent to which evaluators understood workload challenges, and the level of research expected by review committees. Moreover, faculty members stated that although some reassigned time for research is available, it is too inconsistent, unreliable, and increasingly competitive to enable ample and reliable time to complete research projects. The same was said regarding sabbatical leaves. Study participants also expressed concern regarding new Administrative Initiatives. Although these initiatives seek to strengthen student learning and enhance academic program quality, faculty expressed concerns regarding the workload implications as well as the low level of faculty input related to these endeavors. Study participants stated that new initiatives were often established by university administration without identifying sufficient resources to carry out such projects. Assessment emerged as a prominent point of contention between faculty and administration. In the area of Professional Development, “study participants noted that these workshops were not always well attended or relevant to the pedagogical interests of faculty. Furthermore, junior faculty reported minimal levels of engagement in professional workshops, largely due to competing pressures and priorities for their time” (:29). Junior faculty also complained that course load reductions for new faculty are not always available. Several obstacles and impediments were also identified in Faculty Hiring Practices. These included the lack of timely search procedures and the lack of competitive salaries in some fields. Additionally, faculty in some departments noted that the recent hiring freeze has created a faculty shortage, which limits their ability to meet the needs of students and accommodate plans for enrollment growth. In the surveys, more than one-third of Part-Time Faculty members were teaching at multiple institutions, approximately two-thirds held non-faculty jobs, and more than half preferred to teach full-time at a CSU institution. However, only 30.5% held doctoral or first professional degrees. Part-time faculty worked fewer average hours per week than part-time faculty at comparable institutions, perhaps due to teaching load limits in the CSU system. CSU parttime faculty were more likely than the national average to employ essay exams, shortanswer exams, research papers and writing assignment, as well as assess multiple drafts of students’ written work. They were less likely to employ laboratory, shop or studio assignments as well as provide service-learning or co-op experiences. They used multiplechoice exams, required students to deliver presentations, and required students to evaluate and provide feedback on each other’s work at rates comparable to the national average of part-time faculty at similar institutions. A large majority of part-time faculty also made changes to their courses over the previous two years to enhance student learning. CSU part-time faculty reported lower satisfaction levels than the national average regarding institutional support for instructional technology, teaching improvement, and workload. They were also less likely to agree that faculty at this institution are rewarded for good teaching, that women and part-time faculty are treated fairly. The majority was also dissatisfied with job security and office space/equipment but satisfied with the level of support to experiment with new teaching approaches and with secretarial support services. In interviews, part-time faculty reported that they were generally disconnected from matters within their departments. In particular, they stated that insufficient evaluation of their teaching limits communication between full and part-time faculty regarding the goals and priorities of the academic programs in which they teach. Professional development opportunities were also not offered at times and in formats conducive to adjunct participation. And finally, part-time faculty were unhappy about their course load limits, which not only force them to teach at multiple institutions to receive a living wage but also scatters the time and energy they can devote to teaching. In the surveys, full-time Librarians reported working an average week of 37.2 hours, while part-time librarians reported an average workweek of 22.4 hours. They reported the highest levels of dissatisfaction regarding (in rank order) time available for research, creative, and other scholarly activities, institutional support for the same activities, and time available for keeping current in their professional fields. High levels of satisfaction were reported for benefits, salary, and overall job satisfaction. The highest levels of disagreement were expressed with the statements that “administrators at this institution consider the concerns of librarians when making policy”, “people at this institution have a clear understanding of what librarians do”, and “librarians are respected by administrators at this institution”. They generally agreed that the criteria for promotion and tenure were clear and that the work environment fosters a balance between work and personal life. In interviews, librarians sought greater recognition for their work as academic professionals. Specifically, they asked for more flexibility in work schedules, more recognition by promotion and tenure committees of their unique contributions, and more cooperation from information technology units, whose functions are integral to the work of librarians. In the surveys, full-time Coaches and Trainers reported an average workweek of 57.3 hours. Part-time coaches and trainers reported an average workweek of 38 hours. They expressed the highest level of dissatisfaction with (in rank order) the quality of athletic fields, facilities, and the venues for practice and competition, institutional support for professional development, and support services, secretarial and/or professional staff. They also reported high levels of disagreement regarding (in rank order) whether people at this institution have a clear understanding of what coaches and trainers do, review processes for promotion appropriately account for the unique context of what coaches and trainers do, the criteria for promotion are a good fit with their professional interests, coaches and trainers are sufficiently involved in campus decision making, and part-time coaches are fairly treated. In the interviews, coaches and trainers described a very demanding workload that involves long hours and a taxing schedule. They believe their workload is not understood well by other constituencies and their needs are not adequately represented in the collective bargaining agreement. Like the Librarians, they also desired greater flexibility in their schedules on order to meet the unique challenges of their job. In the surveys, full-time Counselors reported an average workweek of 43 hours, while part-time counselors reported an average workweek of 28.5 hours. Large numbers of counselors were dissatisfied with the time available for research, creative, and other scholarly activities and institutional support for those activities. They also reported high levels of disagreement regarding whether administrators consider the concerns of counselor when making policy, counselors are sufficiently involved in campus decision making, people have a clear understanding of what they do, the criteria for tenure and promotion are a good fit for their professional interests, and the review processes for tenure and promotion appropriately account for their unique work context. In the interviews, counselors expressed concern regarding low staffing levels especially in light of students’ increased needs. They also desired greater opportunity to teach and more flexibility in their work schedules enabling them to do so. They also felt that the larger university community did not appreciate the nature of their creative activities and that their evaluation for promotion and tenure was especially problematic given this along with the fact that their DEC consists of one supervisor who does not understand the faculty perspective.