Fact Sheet on After

advertisement

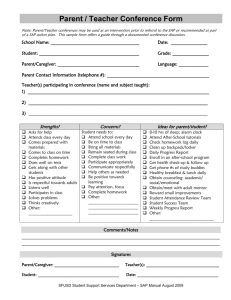

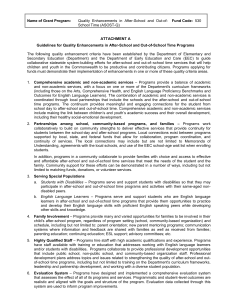

FACT SHEET ON AFTER-SCHOOL PROGRAMS Fact One: Non-school hours represent the single largest block of time in the lives of American youth. American youth only spend about 32% of their waking hours in school. By contrast, about 40% of young people’s waking hours are discretionary – not committed to other activities such as school, homework, meals, chores or working for pay.i The Afterschool Alliance reports that 25% of youth, K-12, are responsible for taking care of themselves in the afterschool hours, while only 11% of youth, K-12, participate in an after-school program. Twenty-two million children want after-school and only 6.5 million children are currently participating in after-school. The need is particularly high for youth in middle school – just 6% are enrolled in after-school programs.ii Fact Two: Young people’s participation in constructive learning activities during non-school hours contributes to their success in school. In a time of increased accountability – when improving young people’s school success is on everyone’s minds – it has been found that elementary-age students who participate in high quality after-school programs demonstrate higher school attendance and higher language redesignation rates. Parents and teachers report that students who participate in afterschool programs are more excited about school and more confident, especially in their academic ability.iii Further, there is evidence that participating in after-school programs has a positive impact on homework completion and school grades.iv Fact Three: In addition to improved academic achievement, youth experience multiple benefits from participation in high quality after-school programs. More than half of middle-grade youth report that their after-school program is giving them the leadership opportunities and life skills they need to become productive members of society; even more report a high level of self-esteem.v Studies spanning more than two decades show that a host of positive benefits result from children’s participation in high quality after-school programs, including: better grades and work habits, improved behavior in school, better emotional adjustment and peer relations, and a greater sense of belonging to the community.vi Fact Four: Children’s regular participation over an extended period of time produces maximum benefits. Children’s gains are more profound if they participate regularly (an average of 3 days per week) and over time – dosage makes a difference.vii The After-School Corporation (TASC) found that youth, PreK-8, who were highly active for two years in after-school programs made the greatest gains on math standardized test scores and had the highest increases in school attendance, especially in the middle grades.viii Another study cites higher participation and long-term involvement (at least four years) as being significantly related to positive achievement on mathematics, reading, and language arts standardized tests.ix Fact Five: Low-income and low-performing youth benefit greatly from after-school programs. A synthesis of research conducted over a 20-year period indicates that out-of-school time activities can have positive effects on the achievement of low-performing or at-risk students in reading and mathematics.x This is particularly true if youth participate in after-school programs consistently, over time and are highly engaged.xi TASC reports that youth from families living at or below the poverty line prior to enrolling in an after-school program gained more points than expected in math scores after both one and two years of after-school participation. Further, Black and Hispanic youth showed the greatest academic gains over similar non-participants.xii Fact Six: Teenagers also benefit from participation in high quality after-school programs. Stanford University professor Milbrey McLaughlin found that adolescents who participate regularly in community-based youth development programs (including arts, sports and community service) have better academic and social outcomes and higher education and career aspirations than other similar teens.xiii Low-income teenagers who participated in the an after-school program in several large American cities were more likely to be high school graduates (63%) compared to non-participants (42%) and more likely to go to post-secondary schools (42%) compared to non-participants (16%).xiv Revised 11/23/05 Fact Seven: After-school programs help to reduce youth crime and other at-risk behavior. Violent juvenile crime triples between 3:00 and 6:00 PM. During these same hours, children face the most serious danger of becoming victims of crime. Children unsupervised during after-school hours are at a greater risk of pregnancy, truancy, receiving poor grades, dropping out of high school, mental depression, and substance abuse. Unsupervised eighth graders in after-school hours are twice as likely to smoke, drink, or abuse drugs.xv Several recent studies have confirmed the relationship between availability of after-school programs and reduced juvenile crime. In one city, boys participating in an after-school program were only one-sixth as likely to be convicted of a crime during their high school years as nonparticipating boys.xvi Fact Eight: Parents and children want quality after-school programs. However, programs are not equitably distributed – low-income youth are much less likely than their affluent peers to have access to them. In a national survey, both parents and students (spanning grades K-12) expressed the desire for after-school activities. In fact, the vast majority of children themselves explicitly recognized the value of quality, supervised out-of-school time activities. But low-income and minority families are far more likely to be dissatisfied with the quality, affordability and availability of options in their communities.xvii Substantial inequalities exist in youth's after-school participation rates by socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity.xviii Fact Nine: After-school programs promote greater parental involvement. Parents of children participating in after-school programs are more likely to attend parent-teacher meetings, after-school events, open houses and volunteer activities. One study reported that parents were more likely to help their children with homework if they were attending an after-school program.xix Fact Ten: There is widespread public support for the expansion of after-school programs. An overwhelming majority of voters (94%) say that there should be some type of organized activity or place for children and teens to go after school every day, and 75% of voters (a near 10% increase since 2000) believe that Federal or state tax dollars should be used to expand daily after-school programs.xx This support is based in part on the public’s recognition that the three-hour difference between children’s school days and their parents’ work days presents significant problems for young people, families and communities. Timmer, S.G., Eccles, J. and O’Brien, I., How Children Use Time, in Time, Goods and Well-Being, Juster, F.T. and Stafford, F.B. (editors), Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research, 1985. ii Afterschool Alliance, America After 3pm Executive Summary, http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/press_archives/america_3pm/Executive_Summary.pdf, May 2004. iii Policy Studies Associates, Inc., Building Quality and Supporting Expansion of After-school Projects: Evaluation Results from the TASC After-School Program’s Second Year, February 2001. iv Kane, T.J., The Impact of After-School Programs: Interpreting the Results of Four Recent Evaluations. A working paper of the William T. Grant Foundation, January 2004. v The After-School Corporation (TASC), Quality, Scale and Effectiveness in After-School Programs, May 2005. vi Vandell, D.L. and Shumow, L., After-School Child Care Programs, The Future of Children: When School is Out, Vol. 9, Num. 2, Fall 1999, David and Lucile Packard Foundation. See also: Miller, B.M., Critical Hours: After-School Programs and Educational Success. Quincy, Massachusetts: Nellie Mae Education Foundation, 2003. vii Simpkins Chaput, Sandra, Priscilla M.D. Little and Heather Weiss. Understanding and Measuring Attendance in Out-of-School Time. Harvard Family Research Project, Issues and Opportunities Out-of-School Time Evaluation Briefs, Number 7, August 2004. viii The After-School Corporation (TASC), May 2005. ix UCLA Center for the Study of Evaluation, A Decade of Results: The Impact of the LA’s BEST After School Enrichment Program on Subsequent Student Achievement, June 2000. x Lauer, P.A., Akiba, M., Wilkerson, S.B., Apthorp, H.S., Snow, D., & Martin-Glenn, M., The Effectiveness of Out-of-School-Time Strategies in Assisting Low Achieving Students in Reading and Mathematics: A Research Synthesis (Updated ed.). Aurora, CO: Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning. www.mcrel.org/PDF/SchoolImprovementReform/5032RR_RSOSTeffectiveness.pdf, 2004. xiWeiss, H. B., Little, P. M. D., & Bouffard, S. M., More Than Just Being There: Balancing the Participation Equation. In H. B. Weiss, P. M. D. Little, & S. M. Bouffard (Issue Eds.) & G. G. Noam (Editor-in-Chief), New Directions in Youth Development: Vol. 105. Participation in Youth Programs: Enrollment, Attendance, and Engagement (pp. 15-31). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Spring 2005. xii Reisner, E.R., White, R.N., Russell, C.A., and Birmingham, J., Building Quality, Scale, and Effectiveness in After-School Programs: Summary Report of the TASC Evaluation. Washington, DC: Policy Studies Associates, 2004. xiii McLaughlin, M.W., Community Counts: How Community Organizations Matter for Youth Development, Washington, DC: Public Education Network, 2000. xiv National Institute on Out-of-School Time, Center for Research on Women, Wellesley College, Making the Case: A Fact Sheet on Children and Youth in Out-of-School Time, January 2003. xv Fight Crime: Invest in Kids. America's After-School Choice: The Prime Time for Juvenile Crime Or Youth Enrichment and Achievement, October 2000. xvi The After-School Corporation, 3:00 P.M.: Time for After School, New York, NY: Author, 1998. xvii Duffett, A. & Johnson, J., All Work and No Play? Listening to What Kids and Parents Really Want from Out-of-School Time. New York: The Wallace Foundation, 2004. xviii Harvard Family Research Project, Analysis of Predictors of Participation in Out-of-School Time Activities. http://www.gse.harvard.edu/hfrp/projects/ost_findings.html, September 2005. xix Kane, 2004. xx Afterschool Alliance, Afterschool Alert Poll Report: A Report on Findings of a Nationwide Poll of Registered Voters on Afterschool Programs, July/August 2003. i PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE WITH APPROPRIATE CREDIT TO THE CHILDREN'S AID SOCIETY www.childrensaidsociety.org/TA Revised 11/23/05