Peer Review - University of Leeds

advertisement

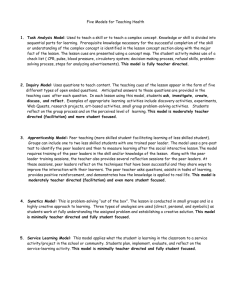

BERA 2005. Evolving diversity within a model of peer observation at a UK university. Ian M. Kinchin. King’s College London. E-MAIL: ian.kinchin@kcl.ac.uk Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, University of Glamorgan, 14-17 September 2005 ABSTRACT A formal programme for the peer observation of teaching was introduced across a UK university during the academic year 2003-4. This process has been evaluated across the 10 schools that constitute the university. The teaching and learning coordinators within each school were consulted about modifications to the basic model presented. Academics (below the level of Head of Department) were then interviewed about their perceptions of the process. From these interviews, seven themes emerged, representing choices made by departments when implementing the programme: efficiency vs. effectiveness; anonymity vs. focus; formative vs. summative; formality vs. informality; frequency of observation; equal vs. unequal partners and teaching vs. research. These themes were then described and given back to the 10 learning and teaching coordinators and the 10 Heads of Schools for their responses. The themes are described with reference to Gosling's (2002) models of peer observation, and Fullan's (1991) 'insights to change'. Patterns of choices made by departments may help them to negotiate the fear generated among academics by peer observation. A model is presented to summarise the central role of observation in university teaching, which considers the role of peer observation at varying levels: the students, the department, the institution and the profession. The implication from this work is that evolving diversity within the model can be viewed as a strength of peer observation, allowing departments to take ownership of the process and develop their own agenda for professional development. It is suggested that for the further development of this model, interdisciplinary peer observation may help to escape the restrictions created by the common focus on the content of teaching. 1. BERA 2005. ___________________ Introduction This paper examines the introduction of a formal system of peer observation of teaching within a research-led university in the UK. The decision was taken to implement this programme within the academic year 2003-4. This was due, in part, to meeting external pressure of the quality enhancement agenda as well as meeting the university’s commitment to maintaining high quality teaching. The implementation of a peer observation of teaching scheme within the institution was a collective decision, which was ratified at the highest levels within the institution. Its aims were to engage as many staff in raising awareness to the processes, as well as, the content of teaching. This was considered to be a positive move to understanding the variety and complexity of teaching strategies and process engaged within the institution. Initially it was envisaged that the outcomes of the process would help the institution identify areas of good or excellent practice so that they could be disseminated across the institution. Equally important was that it could produce a mechanism by which developmental needs could be identified in a secure and supportive environment. The peer observation of teaching (sometimes referred to by colleagues as ‘peer review’) as described in this paper, is defined as an intentional process of observation in which a university teacher (lecturer) sits in on a teaching session of a colleague with the express intention of offering feedback as a ‘critical friend’. In the context described herein, this is not linked to staff appraisal, does not contribute to a postgraduate teaching certificate, is not ‘graded’, and is not restricted to ‘new’ lecturers. In preparation for the introduction of peer observation, a series of seminars was offered to staff. Over 500 members of staff attended these seminars, where discussion focused on possible models that could be adopted. The models put forward by Gosling (2002), (Table 1), were used as a focus for discussion and analysis. 2. BERA 2005. Table 1 Models of Peer Observation of Teaching (after Gosling, 2002). Characteristic evaluation model development model peer review model Who does it & to whom? Senior staff observe other staff teachers observe each other Purpose Identify underperformance, confirm probation, appraisal, promotion, quality assurance, assessment Report/judgement Educational developers observe practitioners; or expert teachers observe others in department Demonstrate competency/improve teaching competencies; assessment report/action plan; pass/fail PGCert Analysis, discussion, wider experience of teaching methods peer shared perception equality/mutuality Outcome Status of evidence Relationship of observer to observed Confidentiality Inclusion Judgement What is observed? Who benefits? Conditions for success Risks authority power expert diagnosis expertise Between manager, observer and staff observed Selected staff Pass/fail, score, quality assessment, worthy/unworthy Teaching performance Between observer and the observed, examiner Institution Embedded management processes Alienation, lack of cooperation, opposition Selected/ sample How to improve; pass/fail Teaching performance, class, learning materials, The observed Effective central unit No shared ownership, lack of impact engagement in discussion about teaching; self and mutual reflection Between observer and the observed - shared within learning set all Non-judgemental, constructive feedback Teaching performance, class, learning materials, Mutual between peers Teaching is valued, discussed Complacency, conservatism, unfocused The pros and cons of each model were discussed within the seminars and it was agreed that the model described by Gosling as the ‘peer review model’ would be most appropriate. Staff were also given guidelines about how to review colleagues and a standard format for the supporting paperwork was provided and described. A three stage format was supported. A preobservation meeting in which the reviewer and reviewee could discuss the session to be observed and issued that might be anticipated. This was followed by the observation itself and then a post-observation meeting in which the merits of the teaching session would be discussed. These discussions would be confidential between the pair and the paperwork would be the property of the lecturer being observed. An additional sheet of paper would record that the staff member had been reviewed and would be passed to the peer observation coordinator within each department. Organizing the mechanics of implementation was devolved to the departments across the university. 3. BERA 2005. It was anticipated that staff would offer some resistance to the idea of peer review at the outset as it would be seen by many as a change to their normal practice. Comments were made about the time the process would take and the unclear nature of the benefits that participation would bring. Though it was never articulated explicitly by the staff at the seminars, there may well have been anxiety about embarking upon a process in which colleagues’ teaching (traditionally a private activity) is suddenly made more public. Such anxiety has been described by Atwood et al. (2000) as a major hurdle to overcome when implementing peer review: … it appears that fear is one of the most compelling reasons to forestall the implementation of peer review. How ironic that disciplines that pride themselves on the peer review of their research … can let peer review of teaching be so immobilizing! (Atwood et al., 2000) This fear combined with the strong traditions of teaching as a private activity, have provided considerable resistance to the universal acceptance by university staff of peer observation as a means of developing teaching skills. The use of peer observation of teaching is well documented, especially in Australia and the USA. Leading in the discussions of peer review have been such authors as Schulman (1987; 1998) and Hutchings (1994) from the Carnegie Foundation, and Angel Brew’s work on professional development (eg. Brew and Boud, 1996). Hutchings (1994) recognised four arguments for engaging in peer observation of teaching: Student evaluations of teaching, though essential, are not enough; there are substantive aspects of teaching with which only faculty can judge and assist each other. Teaching entails learning from experience, a process that is difficult to pursue alone. Collaboration among faculty is essential to educational improvement. The regard of one's peers is highly valued in academia; teaching will be considered a worthy scholarly endeavour--one to which large numbers of faculty will devote time and energy--only when it is reviewed by peers. Peer review puts faculty in charge of the quality of their work as teachers; as such, it is an urgently needed (and professionally responsible) alternative to more bureaucratic forms of accountability that otherwise will be imposed from outside academia. 4. BERA 2005. These ideas were promoted during the staff seminars described above. Some members of staff were clearly aware of the potential offered by peer observation. As one member of staff put it: From the individual lecturer’s point of view, peer observation is by far the most informative form of feedback, particularly as nuances can be discussed and the exact manner of teaching delivery and its anticipated outcomes can be decided beforehand in a bespoke manner for each individual observation.’ _______________ Methods This research takes the approach of hypothesis-generating rather than hypothesis testing (Brause and Mayher, 1991). Initial discussions were undertaken with Teaching and Learning Coordinators (members of academic staff with a responsibility for coordinating teaching and learning activities within the Schools). This helped to focus on key issues and allowed the tentative identification of emerging themes. The next step was to conduct interviews with colleagues across the college. Descriptions given in the research literature of attempts to achieve blanket coverage of staff within an institution have been met with very low response rates (eg. Closser, 1998), making efforts to achieve generalisability nonviable. It was therefore felt to be more important to focus on the quality of data gathered rather than the quantity of data. Data gathered for this study has been sufficient to confirm and saturate categories (ie. issues of concern regarding the process of peer review across the college), generating an increasingly stable agenda to guide subsequent data collection (Guba and Lincoln, 1989). Further sampling confirmed the findings. Therefore, in deciding upon the size of the sample of staff consulted, there is simply a trade-off between generalisability and practicality. Interview data were collected from 20 colleagues (academic staff with a range of experience across the Schools – all below Head of Department level). Quotes from these are used below to illustrate points throughout the text. Themes were then described and presented to Heads of Schools (and back to Teaching and Learning Coordinators) for their consideration, making the total number of academic staff consulted 40. This research is designed to raise awareness of issues to be resolved, rather than to suggest a universal solution that will fit across the university or could be applied to other institutions. However much a researcher is aware of regularities and themes across the schools (when viewed from the outside), those within the schools focus on perceptions of uniqueness that make one school’s needs feel different to those of the next (ie. the view from within a discipline is unavoidably distorted). Disciplinary styles influence the way scholars approach learning and teaching just as it does their research methodology and perspectives of learning, (Marcus, 1998). A disciplinary style comprises, at its core, what Schwab so elegantly 5. BERA 2005. distinguished as ‘substantive and syntactic structures: the “conceptions that guide inquiry” and the “pathways of enquiry” (scholars) use, what they mean by verified knowledge and how they go about verification’ (1964: 25, 21). What Schwab is intimating is that disciplinary style influences the problems academics choose to engage in, the methods used to explore the problems and the nature of the arguments that develop from those explorations The aim of this research is not to compare departments or conclude that one department runs a better observation programme than the next. Rather the point is to identify and illustrate the evolving diversity within the college that has arisen as a consequence of choices made. Whether these choices were made consciously or subconsciously, by raising the profile of these choices, it is hoped that departments will reflect upon them and use these reflections to justify the direction of future developments, enabling peer observation of teaching to make its contribution to ‘enhancing the student experience’. All interviewees were guaranteed total anonymity and so individuals (their status and departments) are not identified. ____________________ Themes. Efficiency vs. effectiveness In applying the model of peer review, departments have each made a choice between having a small team of reviewers within the department (‘development model’), or having everyone act as reviewer and reviewee (‘peer review model’). The use of a group of ‘specialist reviewers’ has been adopted in some departments and has allowed them to ‘complete’ the process quickly. This view of completion seems to overlook the developmental intention of the process. The research literature suggests that such an approach can be improved by rotating the group of staff who are trained as observers so that more of the staff within a department are involved in the process (Hammersley-Fletcher and Orsmond, 2004). This specialist reviewer adaptation (allied to Gosling’s ‘development model’), may help to achieve consistency within the process, particularly if an appropriate discourse of peer review develops among the reviewers within (and possibly between) departments. However, time for such dialogue does not seem to have been given a high priority, and the absence of such a discourse may have an isolating effect upon the reviewers. I can’t comment on what happened in any of the others, because I haven’t spoken to any of the other reviewers. It might be sensible for us to have a little session between us. Such an approach also loses one perceived benefit to most members of the department – that of observing others teach as part of a mutual learning experience. This is seen to be of particular importance (and interest) to new and inexperienced lecturers who would like to see how others do it: 6. BERA 2005. we will often take one of the younger, newer people in the department and send them in to review someone like X, for example. He is a star man … magician. He’s an excellent lecturer. Therefore the idea is that people can go in and learn from good lecturers. Application of this model also implies that the process can be completed and set aside, as an adjunct to normal teaching rather than as a part of it: that way we did it efficiently. We had two people that discussed everything and it all got done. If you involve lots of people you don’t get all the feedback returned and youcan never have closure. The effectiveness of the process can be hampered by a lack of clarity regarding the aims of peer review and a failure to contextualise the process explicitly for those involved: What are the explicit aims of what peer review is supposed to achieve? In spite of all the excellent guidelines, I am not really sure what the aims are. Such comments suggest a lack of effective dialogue within the department before implementation and reflects a view of peer observation as an ‘imposition’ rather than an ‘opportunity for development’: we all did it, because we were just told to do it. I don’t remember who told us to do it. This may also be related to the timing of the introduction of the process, just before a quality assurance audit – an extrinsic motivator. The level of engagement (emotional and intellectual) with peer review crucially defines the rewards an individual will perceive from involvement with the process. Smyth (2003) has emphasised that transformations in practice rely on the emotional engagement of teachers as well as the intellectual engagement. This is linked with feeling ‘safe’ during the process – for many helped by anonymity; equal status within the pair and independence from appraisal. Within a ‘safe’ environment, colleagues may see beyond peer review as a tick-box exercise, and begin to engage with it as a developmental process as suggested by some of the interviewees: If colleagues would choose more demanding scenarios to be observed – one that causes them real concern – they would gain more from it. By choosing a safe, comfortable teaching situation to be observed (as many of our less enthusiastic colleagues do) there is less to be gained in terms of professional development as teachers. 7. BERA 2005. I actually thought to myself I would take the opportunity to be peer reviewed in the setting of a challenging session. I thought that actually it would be the most useful time to have feedback on what was going on. I was having difficulty with a session and I wanted to work out why. Maybe many of my colleagues would do the same thing but I think that would be nice to encourage people to do that. The level of engagement with the peer review process also depends on lecturers’ professional identities (eg. Åkerlind, 2004) – whether you consider your stance to be from within or without the teaching community, and what you consider your role to be within that community: If you say “I am a medic/historian/engineer”, then the process may seem less relevant. But if you say, “I am an educationalist”, as many of us do, then the rationale for peer review becomes clear. Anonymity vs. focus If peer review is anonymous, departmental heads cannot then focus on an individual’s developmental needs and so the department has to be treated as a homogenous body. If however you remove anonymity, you may inhibit the honesty of the process with individuals (understandably) reluctant to hold up their frailties for wider scrutiny. Anonymity of review means that there is no way of establishing a picture of the overall student experience of teaching on any given course. It may be helpful to construct an image of consistency of teaching and/or diversity of teaching from a student viewpoint. Links between peer review and student evaluations of teaching are viewed in general terms within some departments (within the constraints imposed by anonymity of peer review). It is seen as a way of complementing student evaluations of teaching, as there are several issues of concern regarding the reliability of student evaluations and their utility for the professional development of teachers (Johnson, 2000). Students are often perceived to like (or dislike) courses/lecturers for the ‘wrong reasons’: Students may say - I don’t like [lecturer x] because he doesn’t give us the answers – he makes us think. Maintenance of anonymity seems to have been a key factor in allowing the development of the peer review process across the university. Removal of anonymity is likely to trigger widespread anger and resentment (though not among those staff who already label themselves as ‘teachers’ and are not heavily involved in research activity – such staff see peer review as a mechanism to gain recognition for their efforts). Overall, the linking of peer review directly to appraisal is likely to be counter-productive and result in ‘less honest’ engagement in the process. 8. BERA 2005. Formative vs. summative Formative review will encourage participants to identify their developmental needs, but this has to be followed up (there should be a mechanism for this and adequate resource provision), and needs to be a year-on-year rolling programme. Summative assessment can be ‘one-off’ and can be completed within a given time frame. This can be linked to appraisal, but is less likely to be ‘honest’ and deliver improvements in teaching quality. Peer review is intended as a formative process of professional development, but for those who are not used to sharing their teaching space, it may initially appear to be appraisal-like: I must admit to being worried about it beforehand and feeling that I was being tested, but actually it has given me confidence that I must be doing something right. From the interviews, little evidence was gained of any awareness among staff of effective mechanisms for the practical dissemination of good practice to occur within departments. This is a problem that is not unique to the institution described (Hammersley-Fletcher and Orsmond, 2004), and suggests that departments are not benefiting as much as they could: My understanding is that the comments go to ‘X’ and he has a look at them. I don’t know what he does with them to be honest. I think the aim was that there should be some way of disseminating that back, but how is that being disseminated back to the lecturing staff? I have to say, I don’t know. it is happening in isolation and there is nowhere we are pooling that information. The consideration of mechanisms for dissemination would seem to be the next logical step in the development of the programme. Comments made by interviewees suggest that in some departments there persists a content-driven view of teaching which seems to cloud the view of ‘enhancing the student experience’, A focus on content within peer review may implicitly support a novice teacher’s model of teaching by maintaining a focus on the agent of teaching and the act of teaching, rather than a more expert model of teaching that focuses on the object of teaching, that is the learners and their needs (eg. Pratt, 1992; Wood, 2000). The peer review process may help to drive this developmental pathway, but only if the developmental purpose of the process is made explicit at the outset, otherwise a focus on content may persist. I’ll get better by being more knowledgeable about my subject – spend more time in the library. 9. BERA 2005. I think that because so many people in [subject] focus very much on the knowledge they are transmitting and less on other things they are transmitting. This also has to do with the departmental dialogue that precedes the implementation of peer review, and the department deciding what is wants to gain from the process. According to Louie, et al. (2002), such a contentdriven view of teaching and learning within higher education has been maintained by a powerful ‘mythology of unexamined beliefs’ and taken-forgranted assumptions about how academics can control their students’ learning. Such myths persist as they serve specific interests, ‘such as administrative convenience and the dominant cultures of academic departments; and they provide excellent excuses for not doing anything much to make teaching better’ (Ramsden, 2003: 86). Formality vs. informality (paperwork) The three part process (pre-observation, observation and post-observation) adopted at this institution is typical of those used in other universities (Hammersley-Fletcher and Orsmond, 2004) and is cited by some interviewees as a strength of the system, providing a focus for those who have not previously engaged in this type of activity. However, form-filling is universally loathed, and a focus on paperwork may deter some colleagues from engaging positively with the process. For some the paperwork involved is not seen to complement the collegiality of the process. It is perceived to add a managerial layer that is not productive and obstructive to dialogue between peers, as observed by Shortland (2004). Effective use of the paperwork to complement the process requires colleagues to engage professionally with peer review: my observer still hasn’t got round to giving me the comments back. He was going to take them away to type them up nicely, and that’s the last I saw of them. For others who are passionate about their teaching, and positive about peer review, a criticism remains that observation of teaching sessions puts the focus on only part of the role of the university teacher: There can be many good aspects of teaching which may not necessarily be identified by this process. For example, the extent to which a lecturer is available to talk to students. For such colleagues, peer observation of teaching is seen to be only the start of a process to improve the recognition of teaching as a scholarly activity that is as valuable as research. Frequency of observation. Most departments within this study seem to carry out observations of teaching once per year for each colleague (given as a minimum requirement 10. BERA 2005. by the university and reinforced in the introductory seminars). Other departments undertake to observe colleagues once per year per course, as different courses may present very different teaching issues (eg. teaching large classes of undergraduates against teaching small groups of masters level students, or teaching in a classroom/lecture theatre against teaching in a laboratory or a hospital ward). The drive for this ‘extra’ observation seems to come from the teachers concerned rather than from the management. For these colleagues, support is seen to be essential for each teaching context. You might be lecturing to the whole cohort (120). Other times you will be doing a practical class of 20 and other times you will be doing a seminar in a much smaller group. Changing contexts for teaching create real stresses among the teaching staff that may impact upon the quality of their teaching: [on the introduction of large teaching groups] We were just told this is what you are doing now, so off you go. So for the first six months of doing it, I had a neck rash every time I entered the classroom. Such stresses could be alleviated by support through peer observation. The departmental model adopted for peer review needs to reflect the size of teaching loads and the diversity of teaching undertaken – though colleagues with little contact time may be those who could benefit most from the observations of a ‘critical friend’. In some departments, there is a significant reliance upon post docs. and other staff who are visiting or on short term contracts – colleagues who have so far been exempted from the peer review process. I don’t think there was a single course where the lecturer was genuinely bad – bar one. It was actually a course where somebody had been brought in from outside to teach it. There is no evidence to suggest that the formal programme has initiated more informal observation of peers, or team-teaching; largely because of the amount of time this would take away from other activities. The amount of informal observation of peers varies enormously between departments. Team-teaching is common in some departments, absent in others. The benefits of peer observation can be immediate: I feel confident that my individual experience of being peer reviewed actually did produce a positive impact on the session that I was leading. More interestingly, perhaps, because I have done that session again, I subsequently was able to further incorporate and consolidate on the other changes that I had made when I was peer reviewed and that was maintained and indeed more than maintained actually. I thought that I was going to have problems with teaching that session again, on the occasion that I did do it most recently, because I had to teach it several times in quick succession to 11. BERA 2005. different groups of students. That is very tiring and a very difficult thing to do. Because I really thought very hard about that session on the occasion when I was peer reviewed some months before, I had that session really quite sorted in my mind and so it wasn’t actually as difficult to do, although it was still quite a challenge. but very often benefits may take some time to become apparent: I am not really sure how much can be improved immediately. You don’t know at the time whether you have been effective. An annual review of such developments would seem to be prudent if there is to be reflection on long-term gains. Pairing (equal vs. unequal partners) Some colleagues have noted that ‘teaching experience’ does not equate with ‘teaching expertise’ and this influences the choice of reviewer (for those who have that choice). This means that immediate linemanagers/departmental heads are not always the first choice (particularly if that individual currently does little teaching). Issues are evident when reviewer and reviewee are of different status within the department: What would I have done if I had been paired with someone .. for instance with the Prof? What if X had done a crap lecture that day? To make it good you probably have to really make sure there is no threat on either side if it is going to be helpful’. A ‘buddy system’ is used in some departments (ie. reciprocal pairs in which each observes the teaching of the other). This eases anxieties generated by the process by helping to remove the perception of threat (particularly where pairs are self-selected rather than imposed). It also reduces the possibility of the dissemination of good practice as the process is governed by a ‘private contract’ within the pair. In departments employing a panel of ‘expert reviewers’, the main criterion for selection appears to be teaching experience: I think it was the people who had been doing it the longest. but there is recognition that more junior colleagues may have much to gain and a valuable contribution to make: in terms of more junior members of staff, it would almost be more valuable for them as a peer reviewer. people who are coming through the [professional development] system often come out with much newer sorts of ideas anyway, and therefore may be good doing peer reviews. 12. BERA 2005. Pairings of unequal status give the process a feel of appraisal and tend to skew the process towards an ‘evaluation model’ or a ‘development model’ rather than a ‘peer review model’: That [having senior colleagues exclusively reviewing junior colleagues] is slightly against the definition of peer review. Pairings must be considered with care. Having ‘randomised’ parings may work for some colleagues, but may generate inappropriate pairings in some instances: If I was being reviewed and I was told that ‘Bloggs’ will review you, and it was someone for whom I felt no professional respect, it would be a complete waste of time. The question to guide pairings should be along the lines of, ‘who would contribute most effectively to this colleague’s professional development as a university teacher?’. Teaching vs. research Whilst peer review of research is regarded as the norm (and indeed is seen to add credibility through journal publications and conference presentations), the same perception is not held universally for teaching (Asmar, 2002). This is associated with an apparent lack of dialogue about teaching and learning within many departments: the day-to-day contact talking about teaching matters has completely gone out of the window. There appears to be no tradition of dialogue on teaching and learning within some (but not all) schools of the institution studied. A common perception among the staff consulted seems to be that if you want to talk about teaching, it is a sign of weakness and there must be a problem. This seems to deter the development of a departmental discourse of teaching in some departments. A widespread belief was evident among lecturers interviewed that good teaching is not rewarded in the same way as good research and so there is less incentive to discuss issues: [lecturer x] gives a tremendous amount to the students. His lectures are highly praised. He is obviously a meticulous lecturer and he has been interested in [subject] education for many years. He does all the right things – he is available to talk to the students, he encourages them and so on – but in the end, he didn’t get any reward for it. 13. BERA 2005. Actually the more teaching I do, the more my career is under pressure. This is a view that is also commented on in other institutions (eg. Wareing, 2004; Young, 2004). The distinction between professional activities creates a hierarchy, with research rated above teaching. Therefore, time taken away from research activity is regarded as ‘non-productive’ because of the perceived link between research output and promotion. You cannot be a star researcher and put in the amount of time that is necessary to deal with things like [peer review] if we treat it all in detail, it will take up quite a lot of time. It might scupper my research for the day. A recent and extensive review of the international literature describing the so-called ‘teaching-research nexus’ has been given by Qamar zu Zaman (2004), and so the exercise need not be repeated here. From the interviews undertaken for this study, evidence for a positive ‘nexus’ seems patchy. If this can be seen within a single institution, it would not seem surprising that the literature reviewed by Qamar zu Zaman appears to be giving mixed messages about the relationship between teaching and research. Many of the interviewees in this study appear to be teaching in areas that are allied to their research interests, but which do not feed directly into their research – particularly colleagues who are in their first year of teaching within the institution. In consequence, many colleagues do not appear to relate their teaching to their research in the manner that is popularly perceived. In addition, the skills needed to be a good researcher are not seen to be the same skills required to be a good teacher and the two activities require contrary personality characteristics – unlikely to be found in the same person (Qamar zu Zaman, 2004). Our interviewees summed this up in their comments: There is this big push isn’t there that good researchers are good teachers. Some are. I don’t think there are many of those around – who can do both. You end up getting to the lofty heights of lectureship and then you start doing some lecturing on the basis of a very strong research background. It doesn’t mean that you are a good lecturer at all. You can become a Professor on the basis of outstanding research work and you might be one of the worst lecturers in the department. The statements given above highlight the continuing and often disturbing tensions related to the research-teaching nexus. A perception has developed in universities that in general, teaching and research are not found to be mutually exclusive. However, and ironically, many feel that while research is found to be positively associated with teaching effectiveness, teaching 14. BERA 2005. loads are considered as having a negative impact on the capacity to undertake research. The teaching-research nexus has left academics in a dilemma, do they concentrate on keeping up with new innovations in teaching and learning, do they try to adapt to a changing student population, do they keep up with their research, or do they try to do all of these? In attempts to resolve their own dilemmas, many academics have looked to the higher education’s reward structures and systems to gain insight and reassurance into which direction to go. The reward system without a shadow of a doubt reveals why so many academics place their research before teaching even if they feel passionately about their teaching. Research is rewarded, teaching is not! A consequence of this is that “the occupation of university teacher no longer automatically offers autonomy and status” (Nixon 1996, p7). Along side the reward systems favouring research, research itself has become more specialised and so less easy to link directly to teaching. Thus the gap between research and teaching has grown. Within the changing landscape of higher education, the teaching-research nexus has not lost any of its fervour or prominence, it has intensified. The intensity has been caused by an increased demand for the need to improve the quality of teaching found in higher education institutions. The debate has taken on other an extra dimension in the face of increased pressure for research excellence from such external assessment procedures as the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE). The dichotomy of research or teaching has yet again taken centre stage, a stage that now includes external regulation and imposed professional development as a means of raising teaching quality. _______________________ Interdisciplinary peer observation One way of helping teachers to broaden their perspective on teaching and learning, may be to promote the idea of interdisciplinary peer observation (rather than the intra-departmental model described above). Whilst there is considerable variation in the emphasis placed on the scholarship of teaching by academics from different disciplines, Lueddeke (2003) concluded that there is some common ground to be explored. The nature of this common ground has been described in detail by Bain (2004). In his study of over sixty teachers in the US, Bain identified themes within ‘exemplary teachers’ conceptions of teaching’ that were seen to transcend disciplinary boundaries. These included recognition that: Knowledge is constructed and not received Mental models change slowly Questions are crucial Caring is crucial Though external observers/researchers may observe such interdisciplinary characteristics, it is understandable why academics need to refer back to 15. BERA 2005. their own discipline as a means of security, but what happens when they emerge from this safe environment and decide to explore the parameters of their discipline within the learning environment? As we mentioned above, fear is a significant barrier to effective peer observation. Palmer (1998) suggests that “by understanding our fear, we could overcome the structures of disconnection with power of self-knowledge” (p37). What is the fear that keeps academics so closely tied to their disciplines? Again as Palmer suggests the answer seems obvious: it is a fear of “losing my job or my image or my status if I do not pay homage to institutional powers” (p.37). However, this perspective does not adequately explain the depth of the issue. Palmer suggests that academics “ collaborate with the structures of separation because they promise to protect us against one of the deepest fears at the heart of being human- the fear of having a live encounter with alien ‘otherness’, whether the other is a student, a colleague, a subject, or a self-dissenting voice within”. Palmer further argues that the reason why there is such anxiety within the community is because: “We fear encounters in which the other is free to be itself, to speak it own truth, to tell us what we may not wish to hear. We want encounters on our own terms, so that we can control their outcomes, so that they will not threaten our view of world and self. Academic institutions offer myriad ways to protect ourselves from the threat of a live encounter. To avoid live encounters, students can hide behind their notebooks and their silence. To avoid a live encounter with students, teachers can hide behind their podiums, their credentials, and their power. To avoid a live encounter with one another, faculty can hide behind their academic specialties. To avoid a live encounter with subjects of study, teachers and students alike can hide behind the pretence e of objectivity…. T o avoid a live encounter with our-selves, we can learn the art of self-alienation, of living a divided life.” (Palmer, 1998, p37) These comments shed light on a significant part of academic life and the engagement necessary within that life to survive, be successful and most of all remain in good standing within ones particular academic framework/ discipline or allegiances. Palmer identifies key aspects of the academics life in terms of components that identify the need to examine the power of belonging to a discipline or allegiance, plus the need to engage with students, learning, teaching and ones own beliefs and values. Within this context it is not surprising that disciplines and discipline approaches to scholarship remain strong, and as a consequence the belief that disciplines also hold the key to teaching and learning. Although academics emphasis the need to understand the various dimensions in the culture of the academy that shape academic attitudes and behaviours, often within academic life, intellectual, affective, and symbolic meanings coalesce around various points of convergence and tension specific to their territory and discipline, (Astin, 1990, Dill, 1991, Tierney and Rhoads, 1994). Such affective and symbolic bonds among academics often underlie such behaviour, despite 16. BERA 2005. elaborate pretensions to the contrary, (Clark, 1983: 74). It is therefore possible to see how the case of fear as Palmer describes significantly influences academic engagement in the higher education community. This engagement is directly reflected in the nature of scholarship, teaching, and learning. It is essential to break down the notion of fear that results in the academic paralysis described by Atwood et al. (2000), in order to understand why academics inhabit their space in the way that they do. Palmer (1998) suggests that the fear of a live encounter is actually a sequence of fears that begins from a fear of diversity. He argues “as long as we inhabit a universe made homogeneous by our refusal to admit ‘otherness’, we can maintain the illusion that we possess the truth about ourselves and the world- after all, there is no ‘other’ to challenge us! But as soon as we admit pluralism, we are forced to admit that ours is not the only standpoint, the only experience, the only way, and the truths we have built our lives on begin to feel fragile.” (p.38). The point here is that Palmer is not referring to diversity merely in terms of students but the whole academic way of life. Disciplines are not the only way to consider issues, nor are they the only way to engage with scholarship, learning and teaching. Understanding different ways of thinking and behaving requires academics to consider different mind sets, the importance of which is emphasised by Walker (2001: 28): ‘the importance of accessing and including other epistemic communities and voices in our own processes of development and reflection’. Interdisciplinary peer observation may provide a way of reducing the fear generated by the process. It would take away the focus on content and therefore remove the idea that differing degrees of subject expertise held by the observer and observee are indicative of an unequal partnership. It is possible that the next phase in the evolution of diversity within the peer observation of teaching will be driven by a move towards interdisciplinary observation. This is the focus of further research here. ______________________ Conclusions The progress made to introduce peer observation across the university in its first twelve months of formal implementation may be mapped against the ‘four main insights for successful change’ described by Fullan (1991): 1. Active initiation and participation of staff After the college had taken to decision to initiate a formal programme of peer observation, staffs were required to participate. Responsibility for this was devolved to Heads of Departments. 2. Pressure and support External pressures were provided by externally-triggered teaching quality assessments, internal support was provided by the programme of staff seminars described above, and by the provision of appropriate paperwork to guide the process. 17. BERA 2005. 3. Changes in behaviour and beliefs (acknowledging that beliefs may change after behaviour has changed). Staff behaviour had to change (to a greater or lesser degree: some departments had previously run an informal peer review process whilst in others, team-teaching is common practice so that having an additional member of staff in the room was not unusual). By concentrating initially on changes in classroom practice (proximal goals) rather than on the beliefs which guide them (distal goals), this work falls within the model of professional development supported by Guskey (2002). Whether staff development needs to take an explicit conceptual change approach (Ho, 2000) or whether effective progress can be achieved by a more covert epistemological shift (Kinchin, 2005) is not yet clear. However, it is clear that teachers’ beliefs (and how they change) are difficult to measure (Clement, et al., 2003), whilst teachers actions may be easier to measure and record. The risk of not considering fundamental beliefs is that teachers may make surface changes to practice rather than the deep changes (supported by convictions) that are being aimed for (Smyth, 2003). 4. Ownership This is indicated by the ways in which departments had modified the model (as originally presented to them) in order to address their own agenda for professional development. As such, the evolving diversity of approach may be interpreted as an indicator that departments are taking ownership of the process. However, direction of development within the themes described (eg. frequency of observation) may indicate increased or decreased engagement. Only with increased ownership of the process and high levels of engagement will departments (and individual teachers) be able to exploit the benefits of peer review as a central part of their practice as university academics (as summarised in Figure 1). Peer review needs to be viewed as a central process within the daily activities of the university academic – related equally to research and to teaching. It is seen to contribute to the enhancement of the student experience on four levels: 1. Students will see their teachers as having greater credibility. 2. Departments are likely to benefit from increased collegiality as lecturers gain a better understanding of the practice of their peers. 3. Institutions can benefit from the dissemination of exemplary practice that can contribute to the raising of teaching quality. 4. The profession will benefit from a greater appreciation of the scholarly nature of teaching and its relationship with research. 18. BERA 2005. LECTURER engaged in TEACHING needed to develop facilitates CREDIBILITY (students) engaged in facilitates ADMIN. subject to adds RESEARCH subject to boosts SELFCONFIDENCE engaged in rooted in discipline-based, pedagogical PEER REVIEW promotes COLLEGIALITY allows QUALITY CONTROL (department) SCHOLARSHIP OF TEACHING (institution) enhances enhances enhances STUDENTS’ LEARNING EXPERIENCE improves (profession) enhances considers linked to REFLECTIVE PRACTICE Figure 1 The central role of peer review. 19. BERA 2005. Whilst the peer observation programme must be tailored to suit departmental needs, it must also mesh with the other demands placed upon academic staff. This is not to say that peer review should be such a smooth process that it should proceed unnoticed: One of the great benefits of it, is to some extent, that it actually interferes with the normal process and it makes you think. Such professional development has to recognise the diversity within the academic staff working across the university and the variety of starting points they will hold (in terms of their development as a teacher), in the same way as diversity among undergraduate students is now being recognised (Asmar, 2002a). Therefore, the emergence of diversity of implementation within the overall model may be interpreted as an indicator that departments are taking ownership of the process and tailoring the process to suit their professional needs. Models of professional development that target specific aspects of academic work in isolation have bee criticized for continuing to support the divide between teaching and research (Reid and Petocz, 2003). By looking at the relationship between teaching and research through concept mapping of knowledge structures, the ideas proposed in this article would help to satisfy Reid and Petocz’s call for a focus on the synergies between research and teaching rather than the distinctions between them (Fig. 1). The direction of development may indicate increased or decreased engagement and so ‘ownership’ may not be directly correlated with ‘engagement’. It also promotes the concept of the professional teacher, as one who continually learns from the practice of teaching, rather than one who has finished learning how to teach (Darling-Hammond, 1999). 20. BERA 2005. ____________________ References Åkerlind, G.S. (2004) A new dimension to understanding university teaching. Teaching in Higher Education, 9, 363 – 375. Asmar, C. (2002) Strategies to enhance learning and teaching in a researchextensive university. International Journal for Academic Development, 7, 18 – 30. Astin, A. (1990) Faculty cultures, faculty values. In W.G. Tierney (ed.) Assessing academic climates and cultures, 61-74. San Francisco, JosseyBass Atwood, C.H., Taylor, J.W. and Hutchings, P.A. (2000) Why are chemists and other scientists afraid of the peer review of teaching? Journal of Chemical Education, 77, 239 – 243. Bain, K. (2004) What the best college teachers do. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press. Brause, R. and Mayher, J. (1991) Search and Re-search: what the enquiring teacher needs to know. London, Falmer Press. Brew, A. & Boud, D. (1996) preparing for new academic roles: a holistic approach to development. International Journal of Academic Development. 1, 17-25 Clark, B. (1987) The academic life: small worlds, different worlds. Princeton, Carnegie Foundation for the advancement of teaching. Clement, M., Clarebout, G. and Elen, J. (2003) University teachers’ beliefs about goals and characteristics of good instruction. International Journal for Academic Development, 8, 159 – 163. Closser, M. (1998) Towards the design of a system of peer review of teaching for the advancement of the individual within the university. Higher Education, 35, 143 – 162. Darling-Hammond, L. (1999) Teacher learning that supports student learning, In: Presseisen, B.Z. (Ed.) Teaching for Intelligence: a collection of articles (pp. 87 – 96) Arlington Heights, VA, Skylight Professional Development. Dill, D.D. (1991) The management of academic culture: Notes on the management of meaning and social integration. In J.L. Bess (ed.), Foundations of American Higher Education, 567-579. Needham Height, MA.Ginn Press Fullan, M.G. (1991) The new meaning of educational change. London, Cassell. Gosling, D. (2002) Models of peer observation of teaching. LTSN Generic centre, now Higher Education Academy: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk Guba, E.G. and Lincoln, Y.S. (1989) Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park, Sage Publications. Guskey, T.R. (2002) Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice, 8, 381 – 390. Hammersley-Fletcher, L. and Orsmond, P. (2004). Evaluating our peers: is peer observation a meaningful process? Studies in Higher Education, 29, 489 – 503. 21. BERA 2005. Ho, A.S.P. (2000) A conceptual change approach to staff development: A model for programme design. International Journal for Academic Development, 5, 30 – 41. Hutchings, P. (1994) Peer review of teaching: from idea to prototype. AAHE Bulletin, 47, 3 – 7. Johnson, R. (2000) The authority of the student evaluation questionnaire. Teaching in Higher Education, 5, 419 – 434. Kinchin, I.M. (2005) The changing philosophy underlying secondary school science teaching in England: implications for teaching in higher education. Education Today, 55(3): In Press September Louie, B.Y., Stackman, R.W., Drevdahl, D. and Purdy, J.M. (2002) Myths about teaching and the university professor: The power of unexamined beliefs. In: Loughran, J. and Russell, T. (Eds.) Improving teacher education practices through self-study (pp. 193–207). London, Routledge/Falmer.. Lueddeke, G.R. (2003) Professionalising teaching practice in higher education: a study of disciplinary variation and ‘teaching-scholarship’. Studies in Higher Education, 28, 213 – 228. Marcus, G.E. (1998) Ethnography through thick and thin. Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press Nixon, J. (1996) Professional identity and the restructuring of higher education, Studies in Higher Education 21, 5-16. Palmer, P.J. (1998) The courage to teach. San Francisco. Jossey-Bass Pratt, D.D. (1992) Conceptions of teaching. Adult Education Quarterly, 42, 203 – 220. Ramsden, P. (2003) Learning to teach in higher education. (2nd Edn.) London, RoutledgeFalmer. Reid, A. and Petocz, P. (2003) Enhancing academic work through the synergy between teaching and research. International Journal for Academic Development, 8, 105 – 117. Schwab, J. (1964) Structure of the disciplines: Meanings and significance. In Ford, G.W. and Pugno, L. (Eds.) The structure of knowledge and the curriculum (pp. 6 – 30). Chicago, Rand/McNally. Shortland, S. (2004) Peer observation: a tool for staff development or compliance? Journal of Further and Higher Education, 28, 219 – 228. Shulman, L.S. (1987) Knowledge and Teaching. Harvard Educational Review, 57, 1-22 Shulman, L.S. (1998) Course Anatomy: the dissection and analysis of knowledge through teaching, in P.Hutchings (Ed.) The course Portfolio. Washington, DC, American association For Higher Education. Smyth, R. (2003) Concepts of change: enhancing the practice of academic staff development in Higher Education, International Journal for Academic Development, 8, 51 – 60. Tierney, W.G. and Rhoads, R.A. (1994) Faculty socialisation as cultural process: A mirror of institutional commitment. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education report No.93-6 Washington DC. 22. BERA 2005. Walker, M. (2001) Action research for equity in teaching and learning. In: Walker, M. (Ed.) Reconstructing professionalism in university teaching. Buckingham, SRHE/OUP, pp. 21 – 38. Qamar uz Zaman, M. (2004) Review of the academic evidence on the relationship between teaching and research in higher education. Department for Education and Skills Research Report Number 506. Available online at: http://www.dfes.gov.uk/research/data/uploadfiles/RR506.pdf Wareing, S. (2004) Research vs. Teaching: what are the implicit values that affect academics’ career choices? Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Society for Research in Higher Education, Bristol, UK, 14 – 16 December. Wood, K. (2000) The experience of learning to teach: Changing student teachers’ ways of understanding teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 32, 75 – 93. Young, P. (2004) Out of balance: lecturer’s perceptions of differential status and rewards in relation to teaching and research. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Society for Research in Higher Education, Bristol, UK, 14 – 16 December. 23.