videolaparoscopic staging of peritoneal surface

advertisement

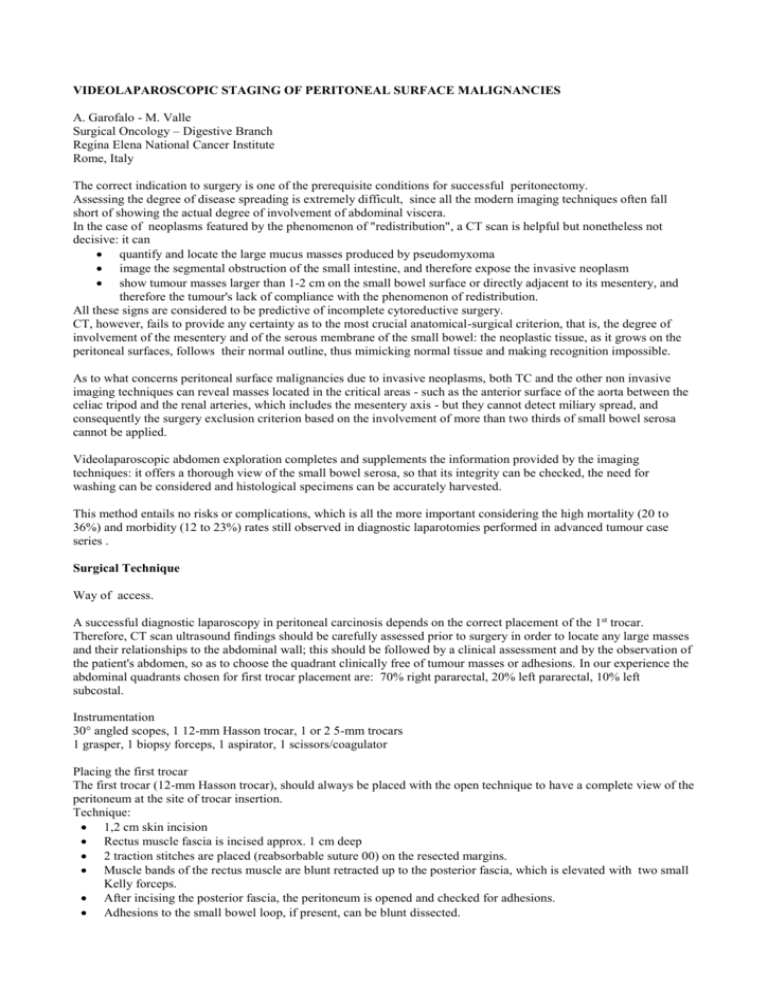

VIDEOLAPAROSCOPIC STAGING OF PERITONEAL SURFACE MALIGNANCIES A. Garofalo - M. Valle Surgical Oncology – Digestive Branch Regina Elena National Cancer Institute Rome, Italy The correct indication to surgery is one of the prerequisite conditions for successful peritonectomy. Assessing the degree of disease spreading is extremely difficult, since all the modern imaging techniques often fall short of showing the actual degree of involvement of abdominal viscera. In the case of neoplasms featured by the phenomenon of "redistribution", a CT scan is helpful but nonetheless not decisive: it can quantify and locate the large mucus masses produced by pseudomyxoma image the segmental obstruction of the small intestine, and therefore expose the invasive neoplasm show tumour masses larger than 1-2 cm on the small bowel surface or directly adjacent to its mesentery, and therefore the tumour's lack of compliance with the phenomenon of redistribution. All these signs are considered to be predictive of incomplete cytoreductive surgery. CT, however, fails to provide any certainty as to the most crucial anatomical-surgical criterion, that is, the degree of involvement of the mesentery and of the serous membrane of the small bowel: the neoplastic tissue, as it grows on the peritoneal surfaces, follows their normal outline, thus mimicking normal tissue and making recognition impossible. As to what concerns peritoneal surface malignancies due to invasive neoplasms, both TC and the other non invasive imaging techniques can reveal masses located in the critical areas - such as the anterior surface of the aorta between the celiac tripod and the renal arteries, which includes the mesentery axis - but they cannot detect miliary spread, and consequently the surgery exclusion criterion based on the involvement of more than two thirds of small bowel serosa cannot be applied. Videolaparoscopic abdomen exploration completes and supplements the information provided by the imaging techniques: it offers a thorough view of the small bowel serosa, so that its integrity can be checked, the need for washing can be considered and histological specimens can be accurately harvested. This method entails no risks or complications, which is all the more important considering the high mortality (20 to 36%) and morbidity (12 to 23%) rates still observed in diagnostic laparotomies performed in advanced tumour case series . Surgical Technique Way of access. A successful diagnostic laparoscopy in peritoneal carcinosis depends on the correct placement of the 1st trocar. Therefore, CT scan ultrasound findings should be carefully assessed prior to surgery in order to locate any large masses and their relationships to the abdominal wall; this should be followed by a clinical assessment and by the observation of the patient's abdomen, so as to choose the quadrant clinically free of tumour masses or adhesions. In our experience the abdominal quadrants chosen for first trocar placement are: 70% right pararectal, 20% left pararectal, 10% left subcostal. Instrumentation 30° angled scopes, 1 12-mm Hasson trocar, 1 or 2 5-mm trocars 1 grasper, 1 biopsy forceps, 1 aspirator, 1 scissors/coagulator Placing the first trocar The first trocar (12-mm Hasson trocar), should always be placed with the open technique to have a complete view of the peritoneum at the site of trocar insertion. Technique: 1,2 cm skin incision Rectus muscle fascia is incised approx. 1 cm deep 2 traction stitches are placed (reabsorbable suture 00) on the resected margins. Muscle bands of the rectus muscle are blunt retracted up to the posterior fascia, which is elevated with two small Kelly forceps. After incising the posterior fascia, the peritoneum is opened and checked for adhesions. Adhesions to the small bowel loop, if present, can be blunt dissected. The Hasson trocar is introduced and held in place by the two stitches placed on the superficial fascia of the rectus muscle. Insufflation values should be in the 8-11 mmHg range. Ascites, if present, can be emptied through the trocar. The ligatures on the superficial fascia of the rectus should be kept tight, and care should be taken to preclude contact between the fluid and the raw abdominal wall, to prevent neoplastic seeding from the trocar port. Abdominal cavity exploration Once the Hasson trocar is in place, the abdominal effusion is completely emptied with the technique described above; in the first step, only the topmost fluid is suctioned. In the second stage, full view of the abdominal cavity is obtained to check for viscus-to-wall adhesions and look for disease-free areas where the 2nd 5-mm trocar can be placed. If the 1st trocar is inserted in the right pararectal fossa, the 2 nd trocar will be placed in the left iliac fossa; if a 3 rd trocar is needed, then it should preferably be placed on the right side, so as to gain access to all abdominal recesses. Cytology samples should be taken under direct vision, after inserting the 2 nd trocar, because the ascites fluid left after the first emptying step, which accumulates into the Morrison and Douglas pouches, is richer in neoplastic cells. Highly mucogenic carcinoses sometimes require a 10 mm trocar in port II, so that a larger suction cannula can be used; or a 5-mm scope can be inserted in port II, which makes it possible to use the 12-mm Hasson trocar as the operating trocar. If loose viscus-to-wall adhesions are present, adhesiolysis should be performed prior to the staging procedure. If the viscera and the abdominal wall are connected by firm adhesions or large masses - more frequently on the midline - a second Hasson trocar should be placed into the contralateral hemiabdomen. During this stage, broad dissections are contraindicated, as they could damage the hollow organs connected to the wall by adhesions. In carcinoses where the histopatological findings are unknown or doubtful, it is mandatory to harvest multiple biopsy specimens from the parietal, diaphragm, omental and pelvic cavity lesions. In case of doubts about the presence of liver metastases or about the involvement of suprahepatic veins or of the celiac tripod, intraoperative ultrasound imaging through the laparoscope is greatly helpful. Sector assessment To assess whether the patient undergoing diagnostic videolaparoscopy is a candidate for peritonectomy, the Peritoneal Cancer Index should be determined, on the basis of the degree of quadrant involvement and size of neoplastic nodules. It is irrelevant which quadrant is explored and staged first. If, however, the first trocar port in the right pararectal fossa is the one used most often, exploration is started in quadrant 1 examining: Round ligament Right hemidiaphragm Gallbladder and liver pedicle. In the absence of midline adhesions, quadrant 2 is examined next, exploring: Lesser omentum Anterior surface of stomach In case of doubt on the degree of carcinosis, the lesser omentum and the gastrocolic ligament may be opened to view the tripod and gain access to the retrocavity. The exploration of quadrant 3 involves: Left hemidiaphragm Spleen Quadrant 4, 0 and 8 will be explored thoroughly: besides the omental apron, regions 9, 10, 11, 12 (jejunum, ileum and mesentery roots) will require inspection as well. After placing the patient in a steep Trendelenburg position, regions 5, 6, 7 are viewed to inspect: Sigmoid colon Intraperitoneal rectum Caecum Last loop of small bowel Douglas pouch Uterus Ovaries In cases featured by a completely retracted mesentery root with massive neoplastic infiltration, the small bowel appears as a stiff skein, blocked by the mesentery which does not shift despite the change in the patient's decubitus: this situation in itself is an absolute contraindication to peritonectomy, as CC0-CC1 cytoreduction cannot be achieved. Personal case series DIAGNOSTIC PATIENT VLS VLS UNFEASIBLE UNDERSTAGING TROCAR SITE INFECTION DIAPHRAM PERFORATION P.O. BLEEDING Perforation 1 326 324 2 5 2 1 1 100 99,39 0,61 1,53 0,61 0,31 0,31 0,31 From August 2000 we performed more than 300 diagnostic videoloaparoscopy procedures in peritoneal carcinomatosis. Many patients had previously undergone at least one laparotomy. The mean time needed for a diagnostic and staging VLS procedure was 30' (range: 15'<>45'). In only two cases, access to the abdominal cavity was made impossible by thick adhesions between the carcinosis-laden small bowel loops and the abdominal wall. Both the cases impervious to VLS evaluation were subjected to midline laparotomy, but it proved not amenable to treatment because of the massive involvement of the small intestine loops, tightly adherent to the abdominal wall. In one case VLS understaged the carcinosis, and on laparotomy, a cast-like mass engulfing the pancreas became visible, which made peritonectomy unfeasible. Complications No major complications occurred, and no neoplastic seeding was detected at trocar sites. In two cases subcutaneous suppuration was observed at the 1 st trocar site; it was treated with targeted topical antibiotic therapy, and subsided within 7 days. Conclusions In our experience, diagnostic VLS in peritoneal carcinosis has a feasibility and reliability rate of 98%; the accuracy of the procedure depends on the surgeon's experience and familiarity with the concepts of PCI and cytoreduction. Consequently, Videolaparoscopic Staging is advantageous only if carried out by the same surgical team who is going to perform peritonectomy.