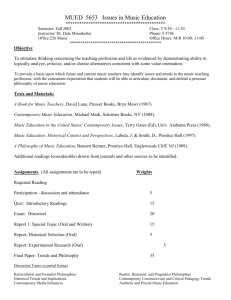

MoMA PS 1 and the Role of the Contemporary Arts Institution

advertisement

The Role of the Contemporary Arts Institution Case Study: MoMA PS 1 Gertrude Stein is often quoted as having observed, “[y]ou can be a museum, or you can be modern, but you can’t be both.”1 Defining the role of the contemporary arts institution continues to be a matter of debate as scholars, critics, artists, collectors, curators, museum directors, and others clash over the proper balance to be struck between preservation of the historical and promotion of the modern. The central function of a museum in the traditional sense is the collection and preservation of objects that have ‘stood the test of time,’ which, ‘given the fallibility of aesthetic judgment,’ has long been considered the least controversial means of isolating quality in art and thus a sound basis for a museum collection.2 This model fails to guide the contemporary arts institution, whose mandate by definition requires a more forward-thinking ethos, and where most, if not all, of the work it collects or displays will be no older than 20 years.3 Nonetheless, the role of the contemporary arts institution reflects some parallels to that of the traditional museum. Its pedagogical function as a resource for public education remains, though altered: rather than displaying works that can ‘be located within a fixed art historical narrative,’4 it projects upon the works it displays the potential of becoming part of that narrative at some point in the future. The contemporary arts institution is no different from a traditional museum in acting as ‘exemplar of civic pride,’5 as government funds continue to support these institutions as they convey the cultural richness of cities, regions, and nations on a global stage. Bruce Altshuler, “Collecting the New: A Historical Introduction” in Bruce Altshuler, ed., Collecting the New Museums and Contemporary Art, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 2005, pp. 1 – 13, at 1. 2 Altshuler at 1. 3 William Sloane Coffin: “[T]en or twenty years should be the limit of modernity.” In Altshuler at 7. 4 Altshuler at 2. 5 Altshuler at 3. 1 1 Indeed, many contemporary arts institutions in the United States serve this ambassadorial function even better than their traditional counterparts, being founded by ‘an enlightened leisure class of women who substituted the eccentric, astonishing, ungroomed art of their unfolding century, and even their own country, for the stately spoils of the Grand Tour.’6 In contrast to traditional art museums, modern institutions face many challenges that are unique to their status as contemporary art museums. First, for works that are deliberately or unintentionally composed of ephemeral materials or concepts, conservation (a principal role of the museum) can be difficult if not impossible.7 Second, the responsibility for selecting works lies subjectively with the individuals who run the museum, whose choices are largely unsupported by the rich legacy of art history and sometimes lack the objective check of market forces to provide benchmarks for the value of acquisitions. Third, even as contemporary art continues to gain value and appeal to a broader audience, the circle of dealers and collectors intimately involved in its trade and display remains terrifically small, with their roles overlapping substantially.8 A prominent example of a successful contemporary arts institution, the MoMA PS 1 was founded in 1971 as the Institute of Art and Urban Resources by Alanna Heiss as ‘a public place for exhibiting contemporary art,’ modeled after the European kunsthalle.9 The initial idea arose out of the desire for a divorce from the traditional museum model and a consequent unburdening of budgets, markets, agendas, and collections.10 Michael Brenson stated its unique purpose as Jeffrey Weiss, “9 Minutes 45 Seconds” in Bruce Altshuler, ed., Collecting the New Museums and Contemporary Art, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 2005, pp. 41 – 54, at 43. 7 Glenn Wharton, “The Challenges of Conserving Contemporary Art,” in Bruce Altshuler, ed., Collecting the New Museums and Contemporary Art, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 2005, pp. 163 – 178, at 166167. 8 Jennifer Steinhauer, “Iron Checkbook Shapes Los Angeles,” New York Times, 7 February 2010. 9 Susan Canning, “P.S. 1: Contemporary Art Center,” New Art Examiner, 28 no5 F 2001. 10 Canning. 6 2 follows: “It defined ‘alternative’ as anything outside the sphere of art-world power at a given moment.”11 Now affiliated with the Museum of Modern Art, PS1 has managed to maintain this enterprising spirit, defying doubters who questioned whether it could preserve its integrity after joining forces with the comparatively stodgy MoMA. The arrangement allows PS 1 the benefits of access to MoMA’s holdings as well as its globally renowned brand to assist in marketing and development, putting PS 1 in a unique position for a contemporary institution, effectively having its cake and eating it too. Apart from its hybrid status as avant-garde museum with unfettered access to institutional ‘comforts,’ PS1 has several additional strengths. Its unique physical location in an old red-brick school building in Queens lent it a ramshackle charm also known as “the Apotheosis of the Crummy Space,”12 and inspired the seminal inaugural exhibit, Rooms, which featured artists such as Gordon Matta-Clark transforming spaces in the physical building into site-specific works. Under Heiss’s direction (she retired in 2008 after nearly 40 years at the helm)13 PS 1 launched a series of innovative Special Projects, including Volume: Bed of Sound, Urban Beach, Warm Up, and the Greater New York exhibition, all of which have played with traditional notions of ‘art’ and ‘viewer’ to critical acclaim. PS1 is interactive in other ways, standing apart from other contemporary institutions by its ‘combination of a studio program and active exhibition space [which] was unusual at its inception and…remains so today.’14 It has a tradition of discovering new artists and rediscovering old ones,15 and it operates a suggested $10 Peter Plagens, “Subway Series,” Art Forum, vol. 37, issue 9 (May 1999), p. 55. Eleanor Heartney, “The Return of the Red-Brick Alternative,” Art in America, vol. 86, issue 1 (January 1998), p. 57. 13 “P.S. 1 Founder Steps Down,” Art in America (February 2009), p. 152 14 Canning. 15 Andrew Goldstein, “Like a European Summer Academy: Klaus Biesenback on P.S. 1 as a place for artists to interact with curators, critics and the public,” Art Newspaper 19 20 F (2010). 11 12 3 admission policy, maintaining its free admission policy for Long Island City residents and NYC public school students, thereby strengthening its position as a valuable community asset.16 The avant-garde and experimental nature of PS1 is central to its function and continuing success. One of PS1’s directors, Klaus Biesenbach (who is also a curator for MoMA), states the contrast between the two museums as follows: ‘PS1 is really a participatory experience. At MoMA most people don’t look at the works as if they were a question, they look at them as if they were an answer….At PS1 the work comes with a set of questions, and the viewer could agree or disagree.’17 By blending its unique contemporary vision with the functions and advantages of a more traditional museum, PS 1 has emerged as a model for new contemporary art institutions worldwide. 16 17 Bill Syken, “Take the E Train,” Art News, (March 1999), p. 47; http://ps1.org/visit/. Goldstein. 4 BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. “P.S. 1 Founder Steps Down,” Art in America, (February 2009), p. 152. 2. Altshuler, B “Collecting the New: A Historical Introduction” in Bruce Altshuler, ed., Collecting the New Museums and Contemporary Art, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 2005, pp. 1 - 13. 3. Canning, S “P.S. 1: Contemporary Art Center,” New Art Examiner, 28 no5 F (2001). 4. Goldstein, A “Like a European Summer Academy: Klaus Biesenback on P.S. 1 as a place for artists to interact with curators, critics and the public,” Art Newspaper, 19 20 F (2010). 5. Heartney, E “The Return of the Red-Brick Alternative,” Art in America, vol. 86, issue 1 (January 1998), p. 57. 6. MacAdam, B “A Space for the 90’s With the Spirit of ’76,” Art News, vol. 96, issue 10 (November 1997), p. 82. 7. MoMA P.S. 1 Website: http://ps1.org/. 8. Plagens, P “Subway Series,” Art Forum, vol. 37, issue 9 (May 1999), p. 55. 9. Steinhauer, J “Iron Checkbook Shapes Los Angeles,” New York Times, 7 February 2010. 10. Syken, B “Take the E Train,” Art News, (March 1999) p. 47. 11. Weiss, J “9 Minutes 45 Seconds” in Bruce Altshuler, ed., Collecting the New Museums and Contemporary Art, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 2005, pp. 41 – 54. 12. Wharton, G “The Challenges of Conserving Contemporary Art,” in Bruce Altshuler, ed., Collecting the New Museums and Contemporary Art, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 2005, pp. 163 – 178. 5