EAL Pedagogy - Teacherworld

advertisement

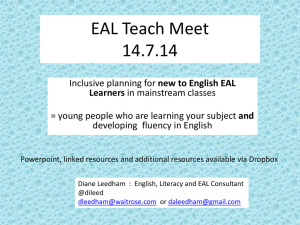

The distinctiveness of English as an additional language Mainstream educationalists whose theories of learning have been influential in the development of EAL pedagogy include Bruner for his work on the link between higher order language functions and thinking and learning skills, Vygotsky for work on language and conceptual development, socially constructed knowledge and 'zone of proximal development', and Maslow for recognizing the importance of sociocultural factors; all children need to feel safe and valued in order to learn. They need a sense of belonging. There has been a great deal of research over the past 2 decades into the development of young bilinguals – international, national, and local including classroom based action research. This has resulted in the development of a number of important theories, principles and knowledge that underpin EAL pedagogy. Internationally the work of Jim Cummins, Virginia Collier and Wayne Thomas, and Stephen Krashen has been influential in the development of pedagogy. Research undertaken in this country on behalf of the DfES or OFSTED has looked at: how well children from ethnic minority backgrounds are actually doing in our schools: Gilbourne and Gipps (1996) Recent research on the achievements of ethnic minority pupils, Gilbourne and Gipps (2000)Educational inequality: Mapping class, race and gender, Bhattacharyya, Ison and Blair (2003) Minority ethnic attainment and participation in education and training the most effective ways of managing support and the characteristics of effective schools: OFSTED (2001) Managing support for the attainment of pupils from ethnic minority groups, Blair and Bourne (1998) Making the difference: Teaching and learning in successful multi-ethnic schools OFSTED will publish new research into effective school support for ethnic minority achievement later this year (2004). The language and literacy skills of bilingual learners: Cameron (2003) More advanced learners of English as an additional language in schools and colleges. This research looked at students in Key Stage 4 and post 16 but Lynne Cameron is currently undertaking similar research looking at the writing of pupils at the end of key Stage 2. See also the work of Eve Gregory and Tony Cline Locally, many teachers of EAL have been involved in classroom based action research. Where this been written up and disseminated through professional organisations such as NALDIC, it has contributed to the development of EAL pedagogy. Language developmen Social and The EAL Learner Cognitive developmen cultural processes Academic developmen Acquiring EAL in the Primary School Context: adaptation of Virginia Collier (1994) This model, adapted from Virginia Collier (1995), describes the main inter-related factors which define the learning situation for the EAL learner and operate within the context of their particular classroom. At the heart of the process is the young bilingual with his/her first language, previous experience of learning, aptitude, learning style etc. The learners will be affected by attitudes to them, their culture, language, religion, ethnicity within the school, beyond the school and in the wider world. Learners’ social and cultural experiences will impact on their progress in language acquisition as well as on their cognitive and academic development. The child of a visiting diplomat learning the language of the host community will probably see the experience as an opportunity to enhance her/his cultural heritage by adding a new language to their repertoire without losing proficiency in the first. A child from a minority group may learn the host language in what are ostensibly the same school circumstances but see the experience as making good a deficit. As Jim Cummins pointed out, the emotional significance of learning a new language in “subtractive” rather than “additive” circumstances is hard to overemphasise. Cummins, the Canadian educationalist and researcher, has developed useful theories and models, which help us to look at the interplay between language development and the cognitive and academic domain BICS Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skill CALP Cognitive and Academic Language Proficiency Cummins adapted the metaphor of an iceberg to distinguish between basic interpersonal communicative skills and cognitive and academic language proficiency (BICS and CALP for short). All children develop conversational skills first, in face to face highly contextualised situations, but take longer to develop the language that contributes to educational success. Cummins acknowledged that some interpersonal communication can impose considerable cognitive demands on a speaker and that academic situations may also require social communication skills. But, generally speaking, children learning an additional language can become conversationally fluent in the new language in 2-3 years but may take 5 years or longer to catch up with monolingual peers on the development of CALP. The distinction between these 2 types of language and their rates of development is now recognised in the OFSTED framework for inspecting EAL in Primary Schools Surface Features L1 Surface features of L2 Common Underlying Proficiency Cummins’s work also highlights the important role of the first language in the child’s learning and in their acquisition of additional languages. Those who have developed CALP in their first language can transfer much of this learning to additional languages. Children who move into a new language environment at an early age can benefit enormously if they are given opportunities to continue to develop their first language alongside English, using both languages for cognitively demanding tasks Bilingual learners face two main tasks in school: they need to learn English and they need to learn the content of the curriculum. These tasks must proceed hand in hand. The vast majority of children learn their first language successfully at home. Children learning an additional language in a classroom are learning under conditions that are significantly different. Learning a language is more than just learning vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation. Children need to use all these appropriately for a whole range of real purposes or functions, functions they will need to perform in order to ‘do’ Maths, Science, History etc. such as questioning, analysing, hypothesising which are clearly linked to thinking and learning skills. High Cognitive Demand e Demand B C (bilingual pupils) Context Embedded Context Reduced D A Low Cognitive Demand This framework, known as Cummin’s Quadrant, can be used to identify the linguistic demands which a classroom activity places on EAL learners. It can support teachers in keeping cognitive challenge appropriately high through the provision of contextual and linguistic support. Learners will need to progress from quadrant A to quadrant B and then to quadrant C. Tasks in quadrant D, being both undemanding and abstract, would have little, if any, learning potential. Contextual support includes opportunities to build on previous experience, teacher modelling, use of visual props and realia, key visuals such as diagrams and time lines, opportunities to work collaboratively in mixed ability groups, to use first language, and most crucially, opportunities to listen and speak in a wide range of situations across the curriculum. ‘The limits of my language are the limits of my life’ (Wittgenstein) Pupils learning EAL will reach their full potential only if attention is paid to their language needs. Effective learning and teaching in the Literacy Hour, Numeracy lesson and across the curriculum require teachers to understand and apply the key principles from EAL pedagogy in their daily practice. References: Bruner J.S. (1975) Language as an instrument of thought. In A. Davies (ed.) Problems of language and learning. London Heinnemann Vygotsky L. (1962) Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press Collier V.P. and Thomas W.P. (1988) Acquisition of cognitive-academic second language proficiency: A six year study Collier V.P. (1989) How long ? A synthesis of research on academic achievement in second language Collier V.P, (1992) A synthesis of studies examining long-term language minority student data on academic achievement Thomas W. P. and Collier V. P. (1995) Research summary of study in progress; Language Minority student achievement and programme effectiveness Thomas W. P. and Collier V. P. (1997) School effectiveness for language minority students. National Clearing House for Bilingual Education Cummins J. (1986) Language proficiency and academic achievement .In J. Cummins and M. Swain, Bilingualism in Education, Longman Cummins J. (1991) Interdependence of first and second language proficiency in bilingual children. In Bialystok (Ed.) Language processing in bilingual children, Cambridge University Press Bilingual Education and Bilingualism Series Cummins.J. (2000)Language Power and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire Jim Cummins, Multilingual Matters Krashen S.D. (1999) Three arguments against whole language and why they are wrong. Portsmouth, NH: Heinnemann Gregory E. (1996) making sense of a new world: Learning to read in two languages. Paul Chapman Publishing Cline T. and Frederickson N. (eds.0 (1996) Curriculum related assessment, Cummins and bilingual children. Multilingual Matters NALDIC, National Association of Language Development in the Curriculum www.naldic.org.uk