ADMISSIONS - Berkeley Law

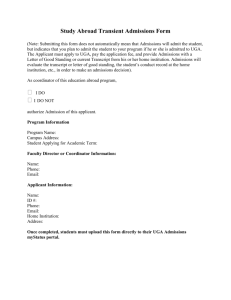

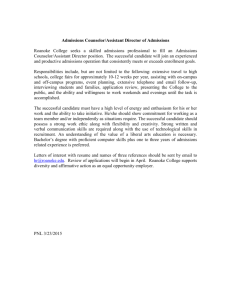

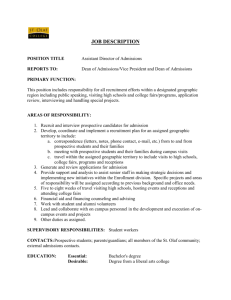

advertisement