offshoring - Economics

advertisement

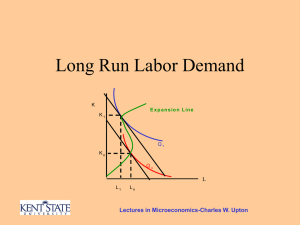

1 Lecture 6 (Ch 7) Offshoring of Goods and Services The provision of a service or the production of various parts of a good in different countries that are then used or assembled into a final good in another location is called foreign outsourcing or, more simply, offshoring. Offshoring is trade in intermediate inputs. The term “offshoring” is sometimes used to refer to a company moving some of its operations overseas but retaining ownership of those operations. - The examples of Intel, Mattel, and Dell suggest there is a gray spectrum to this definition. In this chapter, we will not worry about the distinction between “offshoring” and “foreign outsourcing” and will use the term “offshoring” whenever the components of a good or service are produced in several countries, regardless of who owns the plants that provide the components or services. Is offshoring different from the type of trade examined in the Ricardian and HeckscherOhlin models? From one point of view, the answer is no: offshoring allows a company to purchase inexpensive goods or services abroad, just as consumers can purchase lowerpriced goods from abroad in the Ricardian and Heckscher-Ohlin models. 2 1. A Model of Offshoring Value Chain of Activities Want to predict which activities are likely to be transferred abroad. Offshoring allows firm to “break apart” the production process, and do the unskilled-intensive activities abroad. Figure 7.1: The Value-Chain of a Product The Value Chain of a Product Any product has many different activities involved in its manufacture. Panel (a) lists some of these activities for a given product in the order in which they occur. The value chain in (b) lists these same activities in order of the amount of highskilled/low-skilled labor used in each. In panel (b), the assembly activity, on the left, uses the least skilled labor, and R&D, on the right, uses the most skilled labor. Because we assume that the relative wage of skilled labor is higher at Home and that trade and capital costs are uniform across activities, there is a point on the value chain, shown by line A, below which all activities are offshored to Foreign and above which all activities are performed at Home. 3 Assumptions On wages: • Foreign wages (both Low-skilled and High-skilled) are less than those at Home: • W *L < WL and W *H < WH. • Also, that the relative wage of low-skilled labor is lower in Foreign than at Home: • W *L/W *H < WL/WH. On Capital and Trade costs • Although labor costs are lower in Foreign, the firm must also take into account extra costs of doing business there. • Higher prices to build a factory or costs of production. • The extra costs of communication or transportation. • In making the decision to outsource, a firm will balance the savings from lower wages against the extra costs of capital and trade. • We assume that these extra costs apply uniformly across all the activities in the value chain—a somewhat unrealistic assumption. Which activities will be transferred? Home firms send the most unskilled-labor intensive activities abroad and to keep the more skilled-labor intensive activities at Home. In Figure 7.1, all activities to the left of the vertical line A might be done in Foreign. We can refer to this transfer of activities as slicing the value chain. Relative Demand and Supply of Skilled Labor: For home country add up the demand for high-skilled labor H and low-skilled labor L for all the activities to the right of line AA for Home. Taking the ratio of these, we graph the relative demand for high-skilled labor at Home, H/L against the relative wage, WH/WL. o This relative demand curve slopes downward because a higher relative wage for skilled labor would cause Home firms to substitute toward lessskilled labor in some activities. Similarly for Foreign country In each country, we can add a relative supply curve to the diagram. o Relative supply curve is upward sloping because a higher relative wage for skilled labor will cause more skilled individuals to enter this industry individuals will invest more in equipping themselves with the skills necessary to earn the higher relative wage. A and A* are the equilibrium relative wage in this industry in each country, and the equilibrium relative employment of skilled/unskilled workers. 4 Figure 7.2: Relative Demand and Supply for Skilled/Unskilled Labor Panel (a) shows the relative demand and supply for skilled labor at Home, H/L, depends on the relative wage, WH/WL. The equilibrium relative wage at Home is determined at A. Panel (b), shows the relative demand and supply for skilled labor in Foreign, H*/L*, depends on the relative wage, W*H/W*L. The Foreign equilibrium is at point A*. Now we will study how the equilibrium changes as Home outsources more activities to the Foreign country. Will see: Offshoirng can lead to a rise in the relative wage rates of the skilled labor. So high-skilled labor gains and low-skilled labor loses in relative terms. Changing the Costs of Trade Suppose now that the costs of capital or trade in Foreign fall. For example: • NAFTA lowered tariffs charged on goods crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. => lower trade costs => makes it easier for U.S. firms to outsource to Mexico. • India in 1991 eliminated many regulations that had been hindering both businesses and communications, and also allowed more foreign investment. These changes made India more attractive to foreign investors and firms interested in outsourcing. With lower trade costs it is now desirable to shift more activities in the valuechain from Home to Foreign. 5 Figure 7.3: Offshoring on the Value-Chain Lower capital or trade cost in Foreign shifts the dividing line from A to B. => move activities in-between A and B from Home to Foreign. => increase demand for relative skilled labor in both countries because Home does less of the lower skill end of its activities and Foreign picks up those. Activities no longer performed at Home (i.e. those in-between A and B) are less skill-intensive than the activities still done there (those to the right of B). This means that the range of activities now done at Home are more skilled-labor intensive, on average, than the set of activities formerly done at Home. Consistent what actually occurred in US: shift in relative demand, and the increase in the relative wage of skilled labor in U.S. A shift of activities from one country to the other can increase the relative demand for skilled labor in both countries. Figure 7.4: Change in the Relative Demand for Skilled/Unskilled Labor With greater outsourcing from Home to Foreign, the relative demand for skilled labor at Home increases, and the relative wage rises from point A to point B. The relative demand for skilled labor in Foreign also increases, because the activities shifted to Foreign are more skill-intensive than those formerly done there. It follows that the relative wage for skilled labor in Foreign also rises, from point A* to point B*. 6 An Application: Wage Patterns in the United States Two methods for classification of high-skilled and low-skilled workers: 1- Education: school dropout, high school graduates, 16 or more years of education 2- Type of work: production” and “nonproduction” workers • Production workers are involved in the manufacture and assembly of goods, whereas nonproduction workers are involved in supporting service activities. • Generally, nonproduction workers require more education, and so we will treat these workers as “high-skilled,” while the production workers are treated here as “low-skilled” workers. Relative Wage of Nonproduction/Production Workers, U.S. Manufacturing • This diagram shows the average wage of nonproduction workers divided by the average wage of production workers (analogous to the ratio of high-skilled to low-skilled wages, which we define later as WH/WL), in U.S. Mfg. • This ratio of wages moved erratically during the 1960s and 1970s, though showing some downward trend. • This trend reversed itself during the 1980s and 1990s, when the relative wage of nonproduction workers increased until 2000. • This trend means that the relative wage of production, or low-skilled, workers fell during the 1980s and 1990s. • In more recent years the relative wage has become quite volatile, falling substantially in 2002 and 2004, then rising in 2005 and 2006. Figure 7.5: Relative Wage of Non-production/Production Workers, U.S. Mfg 7 Relative Employment of Nonproduction Workers in US Mfg.: A steady increase in the ratio until the early 1990s. => firms were hiring fewer production workers relative to nonproduction workers. During the 1990s, there was a fall in the ratio and then a rise again after 2000. From 1968 to the early 1983 relative supply of college graduates increased. • This is consistent with the reduction in the relative wage of nonproduction workers. But the story changes after 1983. • The rising relative wage of nonproduction workers should have led to a shift in employment away from nonproduction workers, but it did not. There must have been an outward shift in the demand for skilled workers since the mid 1980’s. Leading to a simultaneous increase in their relative employment and in their wages. Figure 7.6: Relative Employment of Non-production/Production Workers, 8 Figure 7.7 Supply and Demand for Nonproduction/Production Workers in the 1980s • • This diagram shows the average wage of nonproduction workers divided by the average wage of production workers on the vertical axis, and on the horizontal axis the employment of nonproduction workers divided by the employment of production workers. Both the relative wage and the relative employment of nonproduction, or skilled, workers rose in U.S. Mfg. during the 1980s, indicating that the relative demand curve must have shifted to the right. Why the relative wages of unskilled workers fell? Because demand for high-skilled workers increased at the expense of low-skilled workers. Increase in RD of skilled workers because of the use of computers and other high-tech equipment is called skill-biased technological change. To explain the shift in relative demand, we can: • Observe the increase in the share of total wage payments going to non-production labor in U.S. manufacturing industries. This captures both the rising relative wage and the rising relative employment of skilled workers. • Analyze the increase in relative wages of non-production labor. • Outsourcing is measured as the intermediate inputs imported by each industry. • High-technology equipment can be measured in two ways: • As a fraction of the total capital equipment installed in each industry. • As a fraction of new investment in capital that is devoted to computers and other high-tech devices. • Table 7.1 reports the results from both of these measures. 9 What factors can lead to an increase in the relative demand for skilled labor? 1- International Trade: Outsourcing The 1980s was also a time of increasing imports into the United States. The HO model predicts that rising imports in one industry will lead to a fall in demand for all factors of production in that industry and that after some time these factors will be employed elsewhere in an economy. In other words, HO predicts between-industry movements in factors of production, from those industries losing comparative advantage to others that are gaining comparative advantage. But the shift in relative demand toward skilled labor shown in Figure 7.7 holds not only for all manufacturing industries in the U.S. but also within many manufacturing industries, and even within individual firms: firms have been substituting away from unskilled labor and toward skilled labor, even as skilled labor is becoming relatively more expensive. There is no explanation in the Heckscher-Ohlin model (or the Ricardian model) for this kind of within-industry shift in labor demand. 2- skill-biased technological change. With the appearance of personal computers in the 1980’s employers started to substitute skilled for unskilled workers leading to an increase in demand for skilled workers Case Study: What explains the increase in RD for skilled workers or the increase in relative wages of skilled worker in US 1979-1990: offshoring or tech. change? Table 7.1 shows the estimated effects of offshoring and the use of high-technology equipment on the wages earned by nonproduction (or skilled) workers. Part A focuses on how these two variables affect the share of wage payments going to nonproduction workers. Part B shows how these two variables affect the relative wage of nonproduction workers. Table 7.1 Increase in the Relative Wage of Nonproduction Labor in U.S. Mfg, 1979–1990 10 Have two ways of measuring high tech-equipment. Using the first measure of high-tech equipment, it appears that offshoring was more important than high-tech capital in explaining the change in relative demand for skilled workers in US during 1979-1990. Using the second measure we see that both offshoring and high-tech equipment are important explanations for the increase in the relative wages, but it is difficult to judge which is more important because the results depend quite a bit on how we measure the high-tech equipment. Summing up, we conclude that both offshoring and high-tech equipment are important explanations for the increase in the relative wage of nonproduction/production labor in U.S. manufacturing. It is both ! Case Study: Change in Relative Wages in Mexico • Relative wages in Mexico began to move upward in the mid-1980s, at the same time that the relative wage of nonproduction workers was increasing in the U.S. • Relative wages move in the same direction in both countries. • However, after the onset of NAFTA in 1994, relative wages move in opposite directions in the maquilladora and non-maquilladora plants in Mexico. Figure 7.8 Relative Wage of Nonproduction/Production Workers, Mexico Mfg. The relative wage in Mexico continued to rise until 1994, when NAFTA began. 11 2. The Gains from Offshoring o The ability of firms to relocate some production activities abroad means that their costs are reduced = => lower prices, benefits to consumers. Simplified Offshoring Model Assumptions o There are only two activities: o Components production QC, and o Research and Development (R&D), QR. o There are two factor inputs low-skilled labor L, High-skilled labor H used to produce the two intermediate goods o QC is an low-skilled-labor intensive (i.e., making parts and components) and o QR is a high-skilled-labor-intensive non-production input (such as R&D, marketing and after-sale services). o A final good Y: QC and QR are bundled together to produce a final good Y (labor or capital are not used in the final good). o All activities take place within a single manufacturing industry. o All three products can be internationally traded. o The costs of capital are equal in the two activities o compare no-trade situation to an equilibrium with trade through outsourcing, to determine whether or not there are overall gains from trade Figure 7.9: No-Trade Equilibrium at Home The line tangent to the isoquant through point A measures the value that the firm puts on components relative to R&D, or their relative price, (PC/PR)A. Amount Y1 of the final good cannot be produced in the absence of offshoring because it lies outside the PPF for the firm. 12 o Suppose that the firm has a certain amount of high-skilled (H) and low-nskilled (L) labor to devote to components and R&D. It is free to move these workers between the two activities. o Given the amount of skilled and unskilled labor used in total, we can graph a production possibility frontier (PPF) for the firm between components and R&D activities, as shown in Figure 7.9. o This PPF looks just like the production possibilities frontier for a country, except that now we apply it to a single firm Equilibrium with Offshoring: Suppose: (PC/PR) W < (PC/PR) A The world relative price of QC is cheaper than Home’s no-trade relative price. => the Home firm can import components at a lower relative price than it can produce them itself. Figure 7.10 Offshoring Equilibrium for the Home Firm The assumption that (PC/PR) W < (PC/PR) A is similar to the assumption that the relative wage of unskilled labor is lower in Foreign, W*L/W*H < WL/WH. 13 With a lower relative wage of low-skilled labor in Foreign, then components assembly will also be cheaper there. It follow that Home will want to outsource components, which is cheaper abroad, while Foreign firms will outsource the skilled-intensive activity, R&D, which is cheaper at Home. Then according to H-O model = => we expect that Home country to export QR (high-skill-intensive intermediate input) and import QC (low-skill-intensive intermediate input). Gains from Outsourcing Within the Firm: Increase in Y from Y1 to Y2 – is a measure of the gains from trade to the Home firm through outsourcing. same total amount of resources + outsourcing = => more final good higher productivity => lower production costs => lower price of Y =>consumer gain Thus: “When a good or service is produce more cheaply abroad, it makes sense to import it than to make or provide it domestically.” In our example, component production is cheaper in Foreign than in Home, so Home imports components from Foreign. There are overall gains from outsourcing. That is our first conclusion: when comparing a no-trade situation to the equilibrium with outsourcing, and assuming that the world relative price differs from that at Home, there are always gains from outsourcing. 14 Change in Terms of Trade If the relative price of components falls from (PC/PR)W1 to (PC/PR)W2, then the Home firm will do even more R&D and less components production, at point B rather than B. The increase in the terms of trade allows the Home firm to produce output Y2 at point C, and the gains from trade are higher than in the initial offshoring equilibrium (points B & C). Figure 7.10: Fall in the Price of Components. Possibility of making a loss o The Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson: o Most noneconomists are fearful when an emerging China or India, helped by their still low real wages, outsourcing and miracle export-led developments, cause layoffs from good American jobs. This is a hot issue now, and in the coming decade, it will not go away. Prominent and competent mainstream economists enter in the debate to educate and correct warm-hearted protestors who are against globalization. Here is a fair paraphrase of the argumentation that has been used recently… Yes, good jobs may be lost here in the short run. But still total U.S. net national product must, by the economic laws of comparative advantage, be raised in the long run (and in China, too). The gains of the winners from free trade, properly measured, work out to exceed the losses of the losers… Correct economic law recognizes that some American groups can be hurt by dynamic free trade. But correct economic law vindicates the word “creative” destruction by its proof that the gains of the American winners are big enough to more than compensate the losers. 15 Does this paraphrase by Samuelson sound familiar? You can find passages much like it in this chapter and earlier ones: saying that the gains from trade exceed the losses. But listen to what Samuelson says next: The last paragraph can be only an innuendo. For it is dead wrong about [the] necessary surplus of winnings over losings… So Samuelson seems to be saying that the winnings for those who gain from trade do not necessarily exceed the losses for those who lose. How can this be? His last statement seems to contradict much of what we have learned in this book. Or does it? Fall in the Price of R&D: Starting at point B, a fall in relative world price of R&D (PC/PR)W ↓=> steeper price line (PR/PC)W. At the new prices Home shifts production to point B', and by exporting R&D and importing components, moves to point C'. Notice that final output has fallen from Y2 to Y3. Therefore, the fall in the price of R&D services leads to losses for the Home firm. Samuelson’s point is that U.S. could be worse off if China or India becomes more competitive in, and lowers the prices of, the products that the U.S. itself is exporting. Figure 7.11: Fall in the Price of R&D A fall in the relative price of R&D makes the world price line steeper (PC/PR)W3. As a result, the Home firm reduces its R&D activities and increases its components activities, moving from B to B along the PPF. 16 U.S. Terms of Trade and Service Exports Examine the evidence for the United States. Foreign competition in R&D => expect (PR/PC)W ↓ Conversely, if the U.S. has been outsourcing in Mfg., then the opportunity to import lower-priced intermediate inputs should lead to a rise in the terms of trade. Figure 7.13 Table 7.2 U.S. Trade in Services, 2008 ($ millions) 17 Figure 7.14 Trade Surplus in Business Services DY Impact of Offshoring on U.S. Productivity Productivity: Over the eight years 1992 – 2000, service outsourcing can explain between 12 and 17% of the total increase in productivity. Despite the small amount of service imports, it explains a significant portion of productivity growth. Table 7.3: Impact of Offshoring on Productivity and Employment in U.S. Manufacturing, 1992-2000 18 3 Offshoring in Services The outsourcing of skilled service activities seems to violate the prediction of our outsourcing model. Why does the model fail when skilled services are outsourced? The brief answer is that the assumptions we made in the outsourcing model are not satisfied when comparing the U.S. and India. Let us examine these assumptions one at a time. 1. Our first assumption was that Foreign wages are less than those at Home, and in addition, that the relative wage of unskilled labor is lower in Foreign that at Home. That assumption holds true for the U.S. and India. Certified public accountants earn $15,000 in India and $75,000 annually in the U.S., so the high-skill U.S. wage is five times higher. But the gap for less skilled workers is much greater. Indian wages for entry level call center employees in urban areas is $2,400 per year, whereas in the U.S. entry level call center employees earn at least $24,000 per year, a wage that is 10 times higher. 2. Our second assumption in the outsourcing model was that the extra costs of capital and of trade in Foreign were spread uniformly over all the activities on the value chain. But this second assumption does not hold in India. The costs of outsourcing relatively unskilled manufacturing activities to India are much greater than the costs of outsourcing skilled service activities. That is in part because manufacturing requires transporting component parts to India, which has a poor transportation infrastructure: ships are frequently delayed at ports and roads are clogged. Policy makers in India are well aware of these difficulties, which have limited their ability to engage in manufacturing outsourcing, as their neighbor China has done. Indeed, in an attempt to encourage other countries to outsource their manufacturing there, India is now proposing free trade zones (i.e. government subsidized areas not subject to regular customs restrictions) which encourage foreign firms to outsource with Indian manufacturing. We can view the creation of free trade zones as decreasing the trade costs associated with manufacturing outsourcing. These zones have been very successful in China at promoting manufacturing exports, particularly in the coastal regions which have better access to shipping routes. Service activities, on the other hand, do not rely as much on transportation but instead require reliable and cheap communication. The communication infrastructure is very good in India, where cell phone charges are less than in the U.S. and Europe. In addition, India has a large number of well-educated individuals who speak English, and is in a time zone that is 12 hours different from the Eastern time zone in the U.S., which can be an advantage for performing some service activities. All these aspects create a compelling logic for firms in the U.S. and Europe to engage in service outsourcing with India, where India has a comparative advantage. Until trade and capital costs across industries are similar as assumed by our outsourcing model, India will continue to have a comparative advantage in performing service activities, not manufacturing activities. 19 Appendix What can explain increasing wage inequality in US? Since the early 1980’s the wage of skilled relative to unskilled workers in U.S has increased. Is this because of Trade with NIC’s? Is this related to the growth of exports of manufacturing goods of NIC’s and a move toward FPE? (WL/WS) (WL/WS)W (WL/WS)* SS (PC/PS) (PC/PS)W (PC/PS)* PC/PS There is skepticism based on 4 observations: 1- According to H-O a K-abundant country such as U.S is expected to export Kintensive goods. This would increase r and decrease w. If so then we should observe (R.K/GDP)↑ and (W.L/GDP)↓. But there has been no change in the distribution of income of K and L. 2- According to SS-Theorem, an increase in the price of skilled intensive good leads to an increase in the wage rate of skilled labor PH-INT↑ =>WH↑. But there is no clear evidence of a rise in the relative price of skilled intensive goods. 3- If increase in the price of skilled intensive good was the reason for an increase in the skilled-unskilled wage gap in U.S. then we should have observe the reverse in unskilled labor abundant countries such as China PH-INT↑ =>WH↓. That is with an increase in the price of unskilled intensive goods the skilled-unskilled wage gap in China should have decreased but this in fact has increased in NIC’s. 4- Trade of advanced countries with NIC’s is a small share of total spending in advanced countries. 20 Non-traded goods and the Harrigan empirical observation Movement in wages over 1980s and 1990s are – not correlated with trade prices (PT) or outsourcing, – but rather with non-traded goods (PNT): – i.e. there is a sharp increase in the price of high-skilled intensive nontraded goods in the U.S.: WH↑ as PH-NT↑ – - as well as a decrease in the price of low-killed-intensive non-traded goods. – WL↓ as PL-NT↓ This finding poses a challenge to the idea that either trade or technology is responsible for the changes in wages. Price of NT High-skilled-intensive goods ↑ Price of NT Low-skilled-intensive goods ↓ = = > this cannot be because of trade or technology (because ∆W is correlated with PNT and not with PT) = = > something else is going on unrelated to international trade