Academic Care - Association of Independent Schools of NSW

advertisement

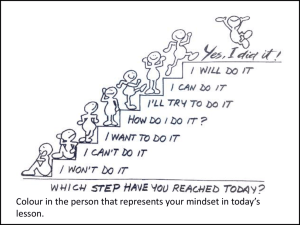

Academic Care : Building Futures Introduction Several schools in the New South Wales Independent sector have created learning teams to develop the pastoral capacity of schools. The focus of the work in schools, through the Community Change Project, has been on learning and psycho-social development as the domain of all teachers, in all classrooms. The project has led to the development of the notion of Academic Care and its significance in enhancing learning and well being through teaching and learning in secondary school subject class classrooms. Strong emphases of the project include the role of data in action research and the importance of learning teams in creating change. Background and Context At the end of 2001, a group of pastoral leaders in NSW schools conducted a survey of 25 schools to ascertain priorities for pastoral care in the sector. The survey results established the need for all teachers to understand their role and impact on the well being of students, as a priority. Concern about the incidence of drug use in the community, depression, self harm, suicide and other maladaptive behaviours, had established a need for pastoral leaders to evaluate and develop the pastoral capacity of schools, in particular, the classroom. The 2001 survey results gave impetus to the need to explore the developmental and situational mechanisms involved in protective processes, particularly in regard to learning and psycho-social development as the domain of all teachers. Given that beliefs about self and learning are shaped by classroom contexts, processes and relationships, and that Pastoral Care and academic progress are inextricably linked, the challenge in schools was to evaluate teachers’ understanding of these links and to determine the extent to which teaching and learning experiences reflect this understanding. Rationale : Pastoral and Academic Care Pastoral Care and academic progress are inextricably linked. Academic Care involves promoting wellbeing through academic structures and processes which are sympathetic to adolescent needs. It is linked to Pastoral Care in its attention to positive learning and developmental outcomes including knowledge of self, self-efficacy, healthy risk taking, goal setting, negotiation, reflection and empowerment. Academic Care has the capacity to strengthen the pastoral work of schools by enhancing protective processes, particularly resilience. Thus, Academic Care is care delivered through the academic domain, most significantly through learning experiences which become protective processes. Characteristics compiled by youth on what they prefer in a teacher (Conger, 1991) include being firm, impartial, and fair ; enthusiastic, warm and positive; adaptive, sympathetic, and sensitive ; using clear communication and being innovative. Whilst not all teachers have training in counselling or care, all teachers, through their relationships, interventions and through the learning experiences which they construct, have the power to enhance or compromise the well-being of students through attention to protective factors. Cheers (2003) claims that, in practice, enhancing protective processes and resilience through Academic Care involves consideration of questions such as What do students need from the curriculum ? What do students need from their teachers ? What do students need from their learning experiences? What do students need from the School community? Academic Care means to assist adolescents to develop positive self-esteem and feelings of well-being and self-efficacy through the School’s academic and organisational structures, and through adults’ relationships with students. 1 Ainscow (1998) reminds us that “ teaching methods are neither devised nor implemented in a vacuum. Design, selection and use of particular teaching approaches and strategies arise from perceptions about learning and learners.” Whilst classroom practitioners are not always active and explicit in teaching and modelling the skills required to develop resilience, these skills lead to an enhancement of classroom climate and are necessary protective processes. More significantly, though, teachers involved have demonstrated that, once their awareness is raised and the elements and indicators of resilient behaviour are made explicit they are able to identify and develop teaching and learning experiences which constitute protectvie processes. Academic Care has the capacity to strengthen the pastoral work of schools, leading to positive outcomes and health protection for students. Academic Care is the process of enhancing (student) learning and well being through attention to developmental, situational and organisational mechanisms in and beyond the classroom. It involves positive interactions/relationships with students and promoting students’ well-being by ensuring that academic structures and interactions are sympathetic to adolescent needs. Thus, by assisting teachers in linking research to their own practice and by providing opportunities for them to create new professional knowledge, teachers are in a position to develop positive psycho-social and learning outcomes through protective processes dialogue with students shaping beliefs about learning teaching and learning processes authentic assessment Each of the four schools shared the aim of enhancing (student) learning and well-being through attention to developmental, situational and organisational mechanisms in and beyond the classroom. By making explicit the elements and processes of what constitutes Academic Care , and , in particular, the development of resilience, teachers are in a position to enhance the self efficacy and well being of the students in their care. Existing school practices and programmes are also being evaluated to explore their role in assisting adolescents to develop positive self-esteem and feelings of well-being particularly through adults’ relationships with them. 2 References AINSCOW, M (1998) Reaching Out to All Learners: Opportunities and Possibilities. Keynote presentation given at the North of England Education Conference, Bradford, January 1998. BENARD, B (1997) Turning It Around for All Youth : From Risk to Resilience. ERIC/CUE Digest, No 126 BENARD, B (1995) Fostering Resilience in Children. ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education Urbana IL. BENARD , B and MARSHALL, K (1997) ' A Framework for Practice : Tapping Innate Resilience ', in Research / Practice Vol 5 No 1 University of Minnesota College of Education and Human Development . BENARD , B and CONSTANTINE, N.A. (2001) California Healthy Kids Survey Resilience Assessment Module: Technical Report. Berkeley, CA : Public Health Institute. BENTLEY, T (1998) Learning beyond the Classroom: Education for a Changing World . London : Demos / Routledge . BLACK, P and WILIAM, D. (1998) Inside The Black Box . School Of Education : King's College London. CHEERS, J (2003) Enhancing Learning and Well-being. Trinity Grammar School, Community Change Report. Trinity Grammar School, Sydney. CHRISTENSEN, S (2001) ' Risk Assessment', DiscussED : Parents' Journal Vol. 9 No.1 St. Catherine's School : Sydney. CLAXTON, G (1999) Wise Up. London: Bloomsbury. CLAXTON, G (1994) Noises from the Darkroom : the Science and Mystery of the Mind. London : Antiquariat. COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA (2000) Mindmatters http://www.currciulum.edu.au/mindmatters Victoria: Curriculum Corporation CONGER (1991) Adolescence and Youth. New York : Harper and Collins DWECK, C (1999) Self-Theories : Their Role In Motivation, Personality, and Development. Essays in Social Psychology : Psychology Press. DWECK, C (1998) Motivation and Self Regulation Across the Lifespan. University Press. Cambridge : Cambridge FAULKNER, D; LITTLETON, K & WOODHEAD, M. (eds) (1998) Learning Relationships In The Classroom. London : Routledge. FULLER, A. (1998) From surviving to thriving: Promoting mental health in young people. Melbourne: ACER. GARDNER, H (1993) Frames of Mind : The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Glasgow: Fontana. 3 GOLEMAN, D (1996) Emotional Intelligence. London: Bloomsbury. GREENHALGH, P (1994) Emotional Growth and Learning. London : Routledge. HAGGERTY, R (1996) Stress, Risks and Resilience in Children and Adolescents. Press Syndicate : University of Cambridge. HARGREAVES, D (1999) ‘The Knowledge Creating School’ , British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol.47,No2,June 1999,p122-124 HAYES, D. LINGARD,B. & MILLS, M. (2002) Productive pedagogies Education links No. 60 HENDERSON, N and MILSTEIN, M (1996) Resiliency In Schools. California : Corwin Press. HOWARD, S ; DRYDEN, J and JOHNSON,B (1997) Teachers' Thinking about Childhood Resiliency : Preliminary Impressions from a Qualitative Study. Paper presented at the Australian Association for Research in Education Conference Dec 1997. HOWARD, S ; DRYDEN, J and JOHNSON, B(1999) 'Childhood Resilience : Review and Critique of Literature', Oxford Review of Education Vol. 25 No. 3 HUNTER, J (2003) Effecting Student Resilience : From Concept to Coalface. Unpublished paper for the 10th International Congress on Mathematical Education, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004 KOTTER, J (1996) Leading Change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. KOTTER, J (1995) Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review. March–April, 1995. McLAUGHLIN, C (2000) 'The Emotional Challenge of Listening and Dialogue', Pastoral Care in Education 18 (3). McLAUGHLIN, C (2001) Dialogues for Development : The English Case Study Of An Action Research Partnership Between Three Schools and A University. Paper presented to European Conference on Educational Research. Lille, France 2001. McLAUGHLIN, C (2001) ' Care and Education - Centre or Periphery ?', Pastoral Care in Education 19 ( 4). p3. NEMEC, M (2003) Paper presented at 4 th International Conference on Drugs and Young People Wellington New Zealand Aotearoa May 2003. OFFICE OF THE BOARD OF STUDIES, NSW (2002) Report: Pedagogy in the K-10 Curriculum. OFFICE OF THE BOARD OF STUDIES, NSW (2002) http://www.boardofstudies.nsw.edu.au/manuals/pdf_doc/curriculum_fw_K10.pdf K-10 Framework PERKINS, D. (1992) Smart Schools : Better Thinking and Learning For Every Child. New York : The Free Press. PERKINS, (1995) Outsmarting IQ: The Emerging Science of Learnable Intelligence . New York : The Free Press. 4 RESNICK, M; HARRIS, L & BLUM, R (1993) The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. Paper published by University of Minnesota Children Youth and Family Consortium. http://www.cyfc.umn.edu/Youth/caring.html ROWE, K. J. & ROWE, K.S. (2002) What matters most: Evidence-based findings for key factors affecting the educational experiences and outcomes for girls and boys throughout their primary and secondary schooling. Melbourne: ACER. RUTTER, M (1990) 'Psychosocial Resilience and Protective Mechanisms ' in HOWARD, S ; DRYDEN, J and JOHNSON, B(1999) ' Childhood Resilience : A review and critique of literature', Oxford Review of Education 25 ( 3 ). RUTTER, M (1999) 'Resilience Concepts and Findings: Implications for Family Therapy ', Journal of Family Therapy Vol. 21 : 119-144 . RUTTER, M & SMITH, D (1995) Psychosocial Disorders in Young People: Time Trends and Their Causes. Academia Europa (Wiley) : Chichester. SIMONS, J ; DEWITTE, S & LENS, W (2000) ' Wanting to Have vs. Wanting to Be : The Effect of Perceived Instrumentality on Goal Orientation ' British Journal of Psychology 91, 335-351 . SWEETING,H and WEST, P.(1994) The Patterns of Life Events in Mid-To Late Adolescence: Markers for the Future? Journal of Adolescence. Vol 17, 1994. WEARE, K. (2000) Promoting Mental, Emotional and Social Health : A Whole School Approach. London : Routledge. WERNER E., & SMITH, R.S., (1982). Vulnerable but Invincible: A Longitudinal Study of Resilient Children and Youth. New York: McGraw Hill. 5 6 7