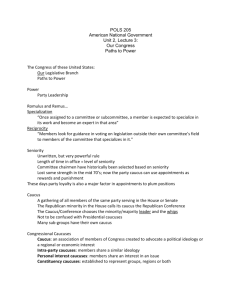

Emergence of Senate Leadership

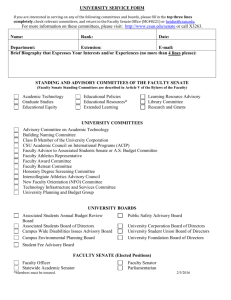

advertisement