1. Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines as a Probe for Better

advertisement

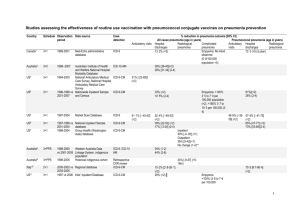

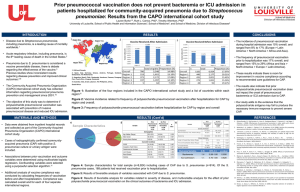

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines as a probe for better understanding pneumococcal respiratory infections Ron Dagan Pediatric Infectious Disease Unit, Soroka University Medical Center and the Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel Respiratory infections are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in young infants and young children globally. Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pnc) is the leading bacterial pathogen in respiratory infections and a major cause of deaths in children <5 years of age (~ 11% of all deaths in this age group [1]). Around 14.5 million episodes of serious pneumococcal disease occurred in the year 2000 in children <5 years with ~ 825,000 estimated deaths, due to serious pneumococcal disease. 95% of these serious pneumococcal disease cases and mortality were attributed to pneumonia.[1] Most serious diseases caused by pneumococcal respiratory disease occur in only 10 countries in Africa and Asia, but pneumococcal respiratory infections are a serious problem globally.[1] Thus it is clear that preventing pneumococcal severe respiratory infections is one of the main global goals.[2] However, what is pneumococcal respiratory disease? The tradition wisdom that pneumococcal pneumonia presenting as alveolar (or lobar) pneumonia is shown to be wrong, although this entity is definitely enriched with bacterial pathogens in general and Pnc in particular. 1 Using any diagnostics tools detects a bacterial pathogen in only a low proportion of LRI and pneumonia. On the other hand, series of efficacy studies with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the US, South Africa, the Gambia and the Philippines showed that the use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) reduced alveolar pneumonia by ~33%, pointing clearly to an important role of Pnc in alveolar pneumonia.[3] However, other endpoints, such as any severe pneumonia (efficacy of 21%) and any clinical pneumonia (efficacy of 8%) were all affected by PCVs, suggesting that Pnc has a role even in the less “classical” pneumonia. Furthermore, the less specific entities were far more common than the classical alveolar pneumonia endpoint, thus a smaller percentage of efficacy in the “non-specific” pneumococcal cases led to a much higher vaccine attributable reduction (VAR) of disease. Thus, for each episode of culture-proven pneumococcal pneumonia, 7 radiologically-proven pneumococcal pneumonia episodes and 19 “clinical pneumonia” episodes could be prevented. [3] Even more surprising findings were that PCVs could reduce what was considered until recently as “pure” viral infections. The first work was from Israel, where a PCV could reduce 20% of bronchiolitis episodes in daycare center toddlers attendees.[4] Later, in a series of studies, Madhi and Klugman showed in South Africa that hospitalization due to virus-positive pneumonia including RSV, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza 1-3 and influenza A and B, were significantly reduced by a PCV.[5] This was the proof of the concept that viral infections often represent in fact a common viral-bacterial co-infection was proven. By reducing the pneumococcal component, severity of the viral infections can be reduced, resulting in a significant reduction in the proportion of the children ending up being hospitalized. 2 After the introduction of the 7-valent PCV (PCV7) to various countries, a reduction in overall outcomes in respiratory infections could be observed. In the US, <30% of hospitalizations due to all-cause pneumonia was seen in the post PCV7 in children <2 years of age. However, at the same time, a 20% reduction of hospitalization due to non-pneumonia LRIs was seen[6] showing that for each case of invasive pneumococcal disease prevented, hospitalization of 14 cases of respiratory infections was prevented by PCV7. The series of studies reviewed above contributed on the one hand to our understanding of the role of pneumocococci in respiratory tract infections, but on the other hand showed that the use of PCV was associated with much greater than expected reduction in respiratory disease. The insights acquired on pneumococcal role in the overall respiratory disease burden and the insights acquired on the PCV role in the reduction of such disease lead to the term “vaccine probe” which means that the use of vaccine can show us its unexpected benefit and teach us about pathogens and epidemiology. We also learned that some serotypes not included in the PCV7 are important, especially for the complicated (or complex) pneumonia, namely pleuropneumonia (or empyema). The most important serotypes are 1, 3, 5, 7F, 14 and 19A, of which only serotype 14 is included in the PCV7. Thus, no one should be surprised that empyema was not reduced after the introduction of PCV7, especially given the fact that another non-Pnc pathogen responsible for this complex entity was MRSA. In fact, an increase in this entity was observed worldwide regardless of PCV7 administration. On the other hand, the new generation PCV10 and PCV13 vaccines contain the “empyema serotypes” 3 and thus after switching from PCV7 to PCV13, we are expecting reduction of empyema. However, the effectiveness of the new PCVs has still to be proven, following vaccine implementation. In summary, the vaccine probe studies has taught us how important PCVs are and that the widespread use of these vaccines can reduce mortality and morbidity. Much more can be learned if additional high quality surveillance programs are set up in countries adopting the vaccine. 4 REFERENCES 1. O'Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, et al. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet 2009;374:893-902. 2. World Health Organization. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for childhood immunization - WHO position paper. Weekly Epidemiological Record. No. 12, 2007, 82, 93-104 (www.who.int/wer). 3. Madhi SA, Kuwanda L, Cutland C,Klugman KP. The impact of a 9-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on the public health burden of pneumonia in HIVinfected and -uninfected children. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1511-8. 4. Dagan R, Sikuler-Cohen M, Zamir O, Janco J, Givon-Lavi N,Fraser D. Effect of a conjugate pneumococcal vaccine on the occurrence of respiratory infections and antibiotic use in day-care center attendees. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2001;20:951-8. 5. Madhi SA, Klugman KP. Efficacy and Safety of Conjugate Pneumococcal Vaccine in the Prevention of Pneumonia (Chap. 22). In: Siber GR, Klugman PK, Makela H, eds. Pneumococcal Vaccines: The impact of Conjugate Vaccine. Washington, DC, ASM Press, 2008:327-346, 6. CDC. Pneumonia hospitalizations among young children before and after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine - United States, 1997-2006. MMWR 2009;6:14 5 6