CHAPTER 20

advertisement

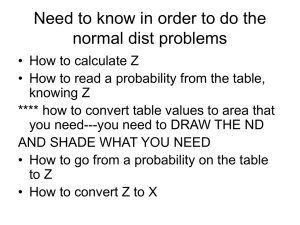

474 CHAPTER 20 Statistical Sampling Concepts for Tests of Controls and Tests of Balances LEARNING OBJECTIVES PART I Review Checkpoints Exercises Problems Cases 1. Explain the role of professional judgment in assigning numbers to risk of assessing control risk too low, risk of assessing control risk too high, and tolerable deviation rate. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 38, 44 21, 45, 46 2. Use statistical tables or calculations to determine test of controls sample sizes. 9, 10, 11, 12 39 21, 45, 46 3. Calculate the effect an test of controls sample sizes of subdividing a population into two relevant populations. 13 4. Use your imagination to overcome difficult sampling unit selection problems. 14, 15 40, 41 5. Use evaluation tables or calculations to compute statistical results (CUL, the computed upper limit) for evidence obtained with detail test of controls procedures. 16, 17 42 6. Use the discovery sampling evaluation table for assessment of audit evidence. 18 43 7. Choose a test of controls sample size from among several equally acceptable alternative. 19, 20 45 21, 46 Ashton Behavioral Cases continues before problem 20.21 PART II 22, 45 36, 37 Review Checkpoints Exercises and Problems Cases 8. Calculate a risk of incorrect acceptance, given judgments about inherent risk, control risk and analytical procedures risk using the audit risk model. 21,22,23,24 70 9. Explain the considerations determining a risk of incorrect rejection. 25, 26, 27 85 10. Explain the characteristics of dollar-unit sampling and its 28, 29, 29, DUS: 41 475 relationships to attribute sampling. 30, 31 11. Calculate a dollar-unit sample size for the audit of the details of an account balance. 32, 33, 34, 35 12. Describe a method for selecting a dollar-unit sample, define a "logical unit," and explain the stratification effect of dollar-unit selection. 36, 37, 38 13. Calculate an upper error limit for the evaluation of dollar-value evidence, and discuss the relative merits of alternatives for determining an amount by which a monetary balance should be adjusted. 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 70 84 82 86 70 71 POWERPOINT SLIDES PowerPoint slides are included on the website. Please take special note of: * * Risk and Materiality in Sampling Illustration of Dollar Unit Sampling as a Hook SOLUTIONS FOR REVIEW CHECKPOINTS 20.1 Use the model AR = IR x CR x DR to solve for different values of Audit Risk (AR) when internal control risk (CR) is given different values. In all cases IR = 0.90 and DR = 0.10, therefore, AR = 0.90 x CR x 0.10 When CR is 0.10 0.50 0.70 0.90 1.00 20.2 AR is 0.009 0.045 0.063 0.081 0.090 or or or or or .9 4.5 6.3 8.1 9.0 percent percent percent percent percent Roberts' method in equation form is: ( RIA at assessed RIA at maximum ) Incremental RIA = RACRTL x ( control risk - control risk ) The method produces low RACRTL at the low control risk levels and high RACRTL at the higher control risk levels. The logic of the method is: "At the lower control risk levels RACRTL should be small because assessing control risk quite low makes a big difference in the substantive sample size and hence in the risk of incorrect acceptance in the substantive balance-audit work, but at the higher control risk levels the RACRTL can be high because assessing control risk slightly too low does not affect the substantive sample size and risk of incorrect acceptance very much." 20.3 Assessing the control risk too low causes auditors to assign less control risk (CR) in planning procedures than proper evaluation would cause them to assign. 476 The result could be (1) inadvertently conducting less audit work than properly necessary and taking more audit risk (AR) than originally contemplated, perhaps to the unpleasant results of failing to detect material misstatements (damaging the effectiveness of the audit) or (2) discovering in the course of the audit work that control is not as good as first believed, causing an increase in the audit work, perhaps at a time when doing to is very costly (damaging the efficiency of the audit). The important considerations when auditing a particular account are questions related to (1) How sensitive is the final substantive audit work to assessing control risk too low?, and (2) Is "recovery"--increasing the substantive audit work at a later date upon discovery of the decision error--more expensive and time consuming than planning more work at the outset (i.e., planning to "overaudit")? 20.4 Assessing the Control Risk Too High The important consideration involved in judging an acceptable risk of assessing the control risk too high is the efficiency of the audit. Assessing control risk too high causes auditors to think they need to perform a level of substantive work which is greater than a proper evaluation of control would suggest. Assessing control risk too high leads to overauditing. Some auditors may be willing to accept high risks of assessing the control risk too high because they intend to overaudit anyway, and the audit budget can support the work. Other auditors want to minimize their work (within acceptable professional bounds of audit risk) and thus want to minimize the risk (probability) of overauditing by mistake. Technically, the risk of assessing control risk too high in relation to an attribute sample is the probability of finding in the sample (n) one deviation more than the "acceptable number" for the sampling plan. For example, if the plan called for a sample of 100 units and a tolerable rate of 3 percent at a .10 risk of assessing control risk too low, the "acceptable number" is zero deviations. (Appendix 13-B.3 shows CUL = 3 percent when zero deviations are found in a sample of 100 units.) The probability of finding 1 or more deviations when the population rate is actually 2 percent is: 20.6 Probability (x > 0 : n = 100, r = .02) = 1 - (1 - r)n = 1 - (1 - 0.2)100 = .867 or 86.7 percent Probability (x > 0 : n = 100, r = .005 ) = (1 - r)n = 1 - (1 - .005)100 = 0.394 or 39.4 percent The "connection" is a direct relationship between control risk and the tolerable deviation rate. (1) When larger values are planned for control risk (say, 0.95, 0.90) in an audit plan, more analytical procedure and test of detail work will be done. Auditors will not rely very much on internal controls. Therefore, not much help is expected from the controls anyway, so the tolerable deviation rate can be larger. The direct relation is: The higher he control risk, the higher the tolerable deviation rate can be. (2) When 477 lower values are assigned to control risk (say, 0.10, 0.20) in an audit plan, less analytical procedure and test of detail work will be done. Auditors intend to rely on internal accounting controls. Therefore, effective compliance with control policies and procedures is important, and the tolerable deviation rate ought to be low. The direct relation is: The higher the planned control risk, the higher the tolerable deviation rate can be. 20.7 The connection between tolerable dollar misstatement assigned for the substantive audit of a balance and tolerable deviation rate used in a test of controls sample is the smoke/fire multiplier judgment. It is the factor by which auditors believe transactions can be exposed to control deviations yet not create dollar-for-dollar misstatements in the related account balance. 20.8 Professional Judgments and Estimates in Test of Controls Attribute Sampling 20.9 a. Risk of Assessing Control Risk Too Low (RACRTL) is a matter of judgment about the importance ("key") characteristic of a particular client control procedure. An auditor can take more risk of assessing control risk too low on unimportant controls than on important ("key") ones. Alternatively, the risk of assessing control risk too low can be considered a constant (say, .10) and the importance of a control can be measured in terms of a smaller or larger tolerable rate. A more logical approach is to use Robert's method to derive RACRTL from the separate judgment of an "incremental risk of incorrect acceptance" for the related substantive audit. b. Risk of Assessing Control Risk Too High is a matter of judgment abut the efficiency of an audit engagement. The risk can be quite high when the audit team is willing to do extensive substantive work anyway. If the work budget is tight, auditors need to find objective ways (e.g., larger test of controls audit samples) to mitigate the risk. c. Tolerable Deviation Rate is a judgment about how many control deviations can exist in the population, yet the control can still be considered effective. Auditors need to be careful about brushing aside findings of deviations. The smoke/fire multiplier is a judgmental connection of the tolerable misstatement in the substantive sample with the tolerable deviation rate in the test of controls sample. d. Expected Deviation Rate in the Population is an estimate, usually based on assumptions or sketchy information, of the imbedded incidence of control deviations. The only use of this estimate in classical attribute sampling is to figure a sample size in advance. The statistical evaluation (CUL calculation) does not use it. e. Population Definition might be called a judgment about identification of the population of control performances that correspond to an audit objective. For example, an auditor would want to be sure he is sampling from a file of recorded documents if his objective is to audit the controls over transaction validity. To figure a test of controls sample size using the Appendix 20-A tables, you need to know: FACT: population size, for finite correction if it is fewer than 1000. JUDGMENT: tolerable deviation rate JUDGMENT: risk of assessing control risk too low (RACRTL) ESTIMATE: estimated deviation number or rate. 478 The risk of assessing control risk too high (RACRTH) is not used in the calculation. 20.10 Enter Appendix 20A for BETA = 5 percent (confidence level = 95 percent) And use N = R/P with R(K=.3, BETA=.05), N= 7.76/(.09)=87 20.11 To figure a test of controls sample size using the Appendix 20.A poisson risk factors, you need to know: FACT: population size, for finite correction if it is fewer than 1000. JUDGMENT: tolerable deviation rate. * These two are needed to get the correct poisson risk factor: * JUDGMENT: risk of assessing control risk too low (RACRTL) * ESTIMATE: estimated deviation number or rate. The risk of assessing control risk too high (RACRTH) is not used in the calculation. 20.12 Enter Appendix 20-A for BETA = 5 percent. N= R(k=2, BETA=.05)/ P= 6.31/.09= 70 20.13 Based on the specifications of risk of assessing control risk too low, tolerable deviation rate and expected population deviation rate, sample sizes would be determined independently for the two populations in the subdivision. If the criteria are at least as stringent for each of the two as they would be for the undivided population, the sum of the two sample sizes would be at least twice the size of the sample figured for the single population (provided both subdivided populations have 1,000 or more units). This is because the formula is used twice, once for each population. 20.14 No, with any random number table arrangement, you can use 1,2,3,4,5,6, or more random digits wherever they appear in the printed table. 20.15 1. 2. 3. Divide the population size by the sample size. obtaining a quotient k. Obtain a random start in the file and select every kth item for inclusion in the sample. If the end of the file is reached, return to the beginning of the file to complete the selection. * When multiple random starts are taken (say, 5), the sampling interval is 5 x k instead of k. 20.16 The UEL is the estimated worst likely deviation rate in the population, with the probability = risk of assessing control risk too low that the actual population deviation rate is even higher. 20.17 Using the Poisson risk factor equation: UEL = Poisson risk factor for 3 errors, BETA=35% = 4.45 = 9.7% Sample Size 46 20.18 The discovery sampling table probability is the probability of finding at least one defined deviation in a sample of a given size, provided the population deviation rate is equal to the critical rate of occurrence. 20.19 The links that connect test of controls sample planning with substantive balance-audit sample planning are these: 479 (1) (2) (3) the smoke/fire multiplier judgment that relates tolerable dollar misstatement in the substantive balance-audit sample to the anchor tolerable deviation rate in the test of controls sample. Roberts' method of calculating RACRTL that relates an audit judgment of incremental risk of incorrect acceptance for the substantive balanceaudit sample to the risk of incorrect acceptance consequences of assessing control risk too low. considering the cost of the substantive balance-audit sample to decide the test of controls sample size and the planned control risk assessment. 20.20 Choose the one that produces the lowest total cost of test of controls sampling and substantive balance-audit sampling. SOLUTIONS FOR REVIEW CHECKPOINTS (Dollar-Unit Sampling in Chapter) 20.21 The objective of test of control with attribute sampling is to produce evidence about the rate of deviation from company control procedures for the purpose of assessing the control risk. Measuring the dollar effect of control deviations is a secondary consideration. The objective of a test of a balance with dollar-value sampling is to produce direct evidence of dollar amounts of error in the account. This is called dollar-value sampling to indicate that the important unit of measure is dollar amounts. Sometimes, dollar-value sampling is called variables sampling just to distinguish it from attributes sampling and the control risk assessment objective. 20.22 Use of the audit risk model to calculate RIA does not remove audit judgment from the risk determination process because all the elements of the model are auditors' judgments and assessments. 20.23 Yes, the benefit from using the audit risk model to calculate RIA is that it captures the independent nature of different audit considerations in its multiplication form, and it enables different auditors who have the same judgments to produce the same RIA. 20.24 TD = AR = 0.015 = 0.20 IR x CR x AP 0.50 x 0.30 x 0.50 You can ask students to illustrate why this comes out the same as the one in the textbook illustration where TD = AR = 0.03 = 0.20 IR x CR x AP 1.0 x 0.30 x 0.50 20.25 An incorrect acceptance decision directly impairs the effectiveness of an audit. Auditors wrap up the work and the material misstatement appears in the financial statements. An incorrect rejection decision impairs the efficiency of an audit. Further investigation of the cause and amount of misstatement provides a chance to reverse the initial decision error. 20.26 The important considerations are cost/benefit and audit efficiency. The "model" is unique to each audit engagement and to each account because costs and relationships will differ from client to client. 20.27 Generally accepted auditing standards define and mention the risk of incorrect rejection, but GAAS takes no "position" on it. GAAS offers no model or method 480 for thinking about RIR. GAAS concentrates attention on the risk of incorrect acceptance and the effectiveness of audit sampling. 20.28 Some of the other names for types of dollar-unit sampling are: combined attributes-variables sampling (CAV), cumulative monetary amount sampling (CMA), monetary unit sampling (MUS), and sampling with probability proportional to size (PPS). 20.29 The unique feature of dollar-unit (DUS) sampling is its definition of the population as the number of dollars in an account balance or class of transactions. Thus, for any given account balance (recorded amount, book balance) the population is defined as the number of dollars. With this definition of the population, the audit is theoretically conducted on a sample of dollar units, and each of these sampling units is either right or wrong. 20.30 Advantages: 1. 2. 3. 4. An estimate of a normal distribution standard deviation is not required. A minimum number of errors is not required for statistical accuracy. Sample sizes are generally small (efficient). Stratification is accomplished automatically. Disadvantages: 1. 2. 3. The DUS assignment of dollar amounts to errors is conservative (high) because rigorous mathematical proof of DUS upper error limit calculations has not yet been accomplished. DUS is not designed to evaluate financial account understatement very well. (No sampling estimator is considered very effective for understatement error, however.) Expanding a DUS sample is difficult when preliminary results indicate a decision that a balance is materially misstated. 20.31 DUS resembles attribute sampling for control deviations in the definition of an error--a dollar is either right or wrong (modified later in connection with tainting calculations). Also, the population is defined as units (dollar) of a uniform size, instead of the varied sizes of logical units, such as customer account balances. 20.32 Larger. DUS sample size varies directly with population size (recorded amount) 20.33 Smaller. DUS sample size varies inversely with the amount of risk of incorrect acceptance. (The RF becomes smaller.) 20.34 Larger. Larger expected misstatement reduces the planned precision P which is the denominator in the sample size planning formula. 20.35 Smaller. DUS sample size varies inversely with the amount of tolerable misstatement. 20.36 The identification of individually significant logical units in an account balance has the effect of reducing the size of the recorded amount population for dollar-unit (DUS) sampling. The individually significant units are removed for 100% audit, and the remainder is the population to be sampled. 20.37 When a $1 unit is selected at random, it "hooks" the logical unit that contains it, making the logical unit the object of the audit. Since larger logical units have more $1-units in them, they are more likely to be chosen in the sample, thus producing a dollar total for the sample larger than the 481 dollar total that would be obtained in an unrestricted random sample in which the logical unit was the sampling unit (because in the latter case, the smaller logical units would have an equally likely chance of selection). 20.38 When two dollar units for the sample fall in the same logical unit, the logical unit is "selected twice." When results are evaluated, any error taint in this logical unit is counted twice. 20.39 Audit of $600,000 with sample of 100. ASI = $6,000. Calculate the UEL at various RIA: RIA Risk Factor UEL 3.00 2.31 1.39 0.70 $ 18,000 $ 13,860 $ 8,340 $ 4,200 0.05 0.10 0.25 0.50 20.40 Audit of $600,000 with sample of 100. ASI = $6,000. Calculate the UEL at various RIA: What is the interpretation of each UEL? RIA Risk Factor UEL 3.00 2.31 1.39 0.70 $ 18,000 $ 13,860 $ 8,340 $ 4,200 0.05 0.10 0.25 0.50 Interpretation: Probability is 5% that actual error exceeds $18,000 10% that actual error exceeds $13,860 25% that actual error exceeds $ 8,340 50% that actual error exceeds $ 4,200 20.41 UEL CALCULATION (RIA = 0.48) Basic Error Likely Error and PGW Factors x Tainting Percentage 0.73 100.00% $ 3,125 1.00 1.00 1.00 90.00% 80.00% 75.00% $ 3,125 $ 3,125 $ 3,125 1. Basic error (0) 2. Most likely error: First error Second error Third error Average Sampling Dollar x Interval = Measurement $ 2,281 $2,813 2,500 2,344 Projected likely error 3. Precision gap widening; First error 0.01 Second error 0.02 Third error 0.01 $ 7,657 90.00% 80.00% 75.00% $ 3,125 $ 3,125 $ 3,125 $ 28 50 23 $ Total upper error limit (0.48 risk of incorrect acceptance) 101 $10,039 Interpretation: The probability is 48% that the error in the account exceeds $10,039. UEL CALCULATION (RIA = 0.05) Basic Error Likely Error Average 482 and PGW Factors 1. Basic error (0) 2. Most likely error: First error Second error Third error Projected likely error x Tainting Percentage Sampling Dollar x Interval = Measurement 3.00 100.00% $ 3,125 1.00 1.00 1.00 90.00% 80.00% 75.00% $ 3,125 $ 3,125 $ 3,125 3. Precision gap widening; First error 0.75 Second error 0.55 Third error 0.46 $ 9,375 $2,813 2,500 2,344 $ 7,657 90.00% 80.00% 75.00% $ 3,125 $ 3,125 $ 3,125 $2,109 1,375 1,078 $ 4,562 Total upper error limit (0.05 risk of incorrect acceptance) $21,594 Interpretation: The probability is 5% that the error in the account exceeds $21,594. 20.42 The one best measure of a sample-based amount for adjustment, arguably, is the projected likely error (provided the projection is made from a sufficiently large sample). The PLM assumes that the error found in the sample is representative of the error in the remainder of the population, and estimates the amount of error that might be found if the entire population were audited. 20.43 The auditing profession members cannot even agree on where to go for lunch, much less agree on a tough concept like sample-based measurement of misstatement amounts in a population of data. Audit situations are all different. The errors in one account must be considered in combination with errors in other accounts. After all, the first pass at an overall materiality criterion is itself not well defined, and the assignment of tolerable misstatement to individual accounts is even less well defined. Reportedly, auditors don't even assess tolerable misstatement anyway. They make ad hoc adjustment decisions in each individual audit and its circumstances. SOLUTIONS FOR KINGSTON CASE 20.44 Determine a Test of Controls Sample Size using Roberts Method Described in solution to 20.2 The test of controls sample sizes were calculated with the Poisson risk factor equation. The tables do not give all the RACRTL's for the problem. (1) Required (for basic analysis): Smoke/fire multiplier = 8.5 TDRCR=.05 = (8.5 x 10,000) / 8,500,000 = .01 Incremental risk of incorrect acceptance = .01 Each RACRTL = .01 / (RIA - RIACR=1.0) for example RACRTLCR=.20 = 01 / (.25 - .05) = .05 Lowest-cost combination ($873) at CR = .20, indicates a test of controls sample of 75 (zero deviations expected) followed by a substantive sample of 81 if no deviations are found. 483 EXHIBIT 20.44-1 KINGSTON COMPANY TEST OF CONTROL SAMPLE SIZE ANALYSIS Test of Control Balance-Audit Control Risk Categories Low control risk Moderate control risk Control risk below maximum Maximum risk CR TDR RIA RACRTL n[c] Cost n[s] .10 .20 .30 .40 .50 .60 .70 .80 .90 1.00 .02 .04 .06 .08 .10 .12 .14 .16 .18 .20 .50 .25 .17 .13 .10 .08 .07 .06 .06 .05 196 75 42 26 16 9 5 4 4 4 $ 588 $ 225 $ 126 $ 78 $ 48 $ 27 $ 15 $ 12 $ 12 $ 12 51 81 96 107 117 125 130 136 136 143 .02 .05 .08 .13 .20 .33 .50 .50 .50 .50 Cost $ 408 $ 648 $ 768 $ 856 $ 936 $1,000 $1,040 $1,088 $1,088 $1,144 TOTAL $ 996 $ 873 $ 894 $ 934 $ 984 $1,027 $1,055 $1,100 $1,100 $1,156 RIA = Risk of incorrect acceptance for the substantive balance-audit sample. RIA = (AR=.05)/[(IR=1.0) x CR x (AP=1.0)] (2) Required (for alternative analysis): Smoke/fire multiplier = 17 TDRCR=.05 = (17 x 10,000) / 8,500,000 = .02 Incremental risk of incorrect acceptance = .02 Each RACRTL = .02 / (RIA - RIACR=1.0) for example RACRTLCR=.20 = .02 / (.25 - .05) = .05 Lowest-cost combination ($729) at CR = .10, indicates a test of controls sample of 107 (zero deviations expected) followed by a substantive sample of 51 if no deviations are found. Differences: Jack's criteria produce smaller test of controls samples at the lower control risk levels, hence smaller total costs and the lowest cost at a lower control risk level. The two alternatives are about the same at the higher risk levels because the test of controls sample reach a minimum size. EXHIBIT 20.44-1 KINGSTON COMPANY TEST OF CONTROL SAMPLE SIZE ANALYSIS Test of Control Balance-Audit Control Risk Categories Low control risk Moderate control risk Control risk below maximum Maximum risk CR TDR RIA RACRTL n[c] Cost n[s] .10 .20 .30 .40 .50 .60 .70 .80 .90 1.00 .03 .05 .07 .09 .11 .13 .15 .17 .19 .21 .50 .25 .17 .13 .10 .08 .07 .06 .06 .05 107 46 25 15 8 5 5 4 4 3 $ 321 $ 138 $ 75 $ 45 $ 24 $ 15 $ 15 $ 12 $ 12 $ 9 51 81 96 107 117 125 130 136 136 143 .04 .10 .17 .25 .40 .50 .50 .50 .50 .50 Cost $ 408 $ 648 $ 768 $ 856 $ 936 $1,000 $1,040 $1,088 $1,088 $1,144 TOTAL $ 729 $ 786 $ 843 $ 901 $ 960 $1,015 $1,055 $1,100 $1,100 $1,153 484 RIA = Risk of incorrect acceptance for the substantive balance-audit sample. RIA = (AR=.05)/[(IR=1.0) x CR x (AP=1.0)] 20.45 Quantitative Evaluation of Compliance Evidence This problem takes Problem 7.28 into the statistical evaluation calculations. The quantitative solutions are entered on 10 sampling data sheets. We have not written any control risk evaluation on these data sheets so you can use them for transparencies in classroom discussion. We believe a good class exercise is to write conclusions determined by students for various samples. Incidentally, under the criteria suggested by the problem data, the small sample sizes are not large enough to support conclusions of UEL less than 4 percent, even when no deviations are found. The next ten pages contain the data sheets for various sample sizes. They are the same as the data sheets in Chapter 7 (Problem 7.27/28), but some statistical criteria and UEL data are entered here. [SEE EXHIBIT 20.45 ON NEXT PAGES) Test of Controls Sampling Data Sheet] SOLUTIONS FOR MULTIPLE-CHOICE QUESTIONS 485 Exhibit 20.45-1 A 486 Exhibit 20.45-1 B 487 Exhibit 20.45-1 C 488 Exhibit 20.45-1 D 489 Exhibit 20.45-1 E 490 Exhibit 20.45-1 F 491 Exhibit 20.45-1 G 492 Exhibit 20.45-1 H 493 Exhibit 20.45-1 I 494 Exhibit 20.45-1 J 495 496 20.46 a. Incorrect. b. c. d. Incorrect. Incorrect. Correct. 20.47 a. Correct. b. c. d. Incorrect. Incorrect. Incorrect. 20.48 a. Incorrect. b. c. Incorrect. Incorrect. d. Correct: a. b. Correct. Incorrect. c. Incorrect. d. Correct. Auditors can think about as many tolerable deviation rates as there are control risk levels. same reason as in a. same reason as in a. same reason as in a. Auditors should associate only one tolerable deviation rate with each possible control risk level. Note this may involve defining deviations to include many conditions. Only one tolerable deviation rate per control risk level. Only one tolerable deviation rate per control risk level. Only one tolerable deviation rate per control risk level. The control risk levels can be arranged in any logical manner an auditor desires. see d. below They may be low, but the level is a judgment the auditor is entitled to make. Tolerable deviation rates should be higher for higher levels of control risk. 20.49 Using N=R/P with BETA=.05; k=0,and P=.06-.03 This is the sample for 1% risk of overreliance, where 11 deviations is about 3% of the sample of 360. This is the sample for 10% risk of overreliance, where 5 deviations is about 3% of the sample of 160. This is the sample for zero expected deviations and 5% risk of overreliance, i.e., a discovery sample size. Some firms budget for a discovery sample size audit and so ignore the expected error rate. This also simplifies audit planning. 20.50 a. b. c. d. Incorrect. Incorrect. Incorrect. Correct. see d. below see d. below see d. below The risks of overreliance should go from low (1%) to high (10%), because the consequences of overreliance (auditing a smaller sample size of customer accounts) becomes less serious. 20.51 a. b. c. d. Incorrect. Correct. Incorrect. Incorrect. UEL=Achieved P= R/n (k=2, BETA=.05) /n =6.30/90=.07 7% 20.52 a. Correct. The interpretation should relate to a worst rate and a risk of overreliance. This answer relates to a lowest rate. This answer relates to certainty instead of risk. This answer relates to certainty instead of risk. b. c. d. Incorrect. Incorrect. Incorrect. 20.53 a., b., and c. d. Correct. should be considered incorrect for the reason given in d, below. However, for the 1%, 5%, and 10% risks of overreliance shown in the tables in Appendix 20A, the UELs for one deviation out of 100 in the sample all exceed 0.04, so the UEL cannot meet any of the tolerable deviations given in the three choices. The decision-maker needs to express a risk of overreliance criterion in order to assess a control risk level. 497 20.54 a. b. c. Incorrect. Correct. Incorrect. d. Incorrect. 20.55 a. Incorrect. b. Correct. c. d. Incorrect. Incorrect. 20.56 a. Incorrect. UEL is greater than the tolerable deviation rate. UEL gives the best conservative measure of deviation rate. Should not jump to the extreme "rejection" conclusion, unless 5% deviation rate is associated with 100% risk. Should not impose nonstatistical manipulation on the decision criteria set up at the beginning of the test. This assessment could be made, but the better conclusion would be related to the actual CUL. The assessed level of control risk should be related to the actual CUL. This is nonsense because the control "passed the test." b. is a better answer, and there's no information that 2% CUL is associated with the minimum level of control risk. The tolerable rate reduced by the allowance for sampling risk is not meaningful. Assess higher than planned control risk because the computed upper limit (7%) is higher than the tolerable deviation rate (5%). The allowance for sampling risk should be added to the actual sample results (sample deviation rate) and not to the tolerable deviation rate. The relation of computed upper limit (7%) greater than tolerable deviation rate (5%) leads to the higher rather than lower control risk assessment. b. Correct. c. Incorrect. d. Incorrect. 20.57 a. b. c. d. Incorrect. Incorrect. Incorrect. Correct: 2.5% is the expected deviation rate. 4.5% is the actual sample deviation rate (9/200) 3.5% is not related to anything. deviations in sample of 200 at 1% risk of assessing control risk too low = 8.0% P=R(k=9, BETA=.05)/200 =15.77/200 =.07855 =.08 20.58 a. b. c. d. Incorrect. Correct Incorrect. Incorrect. limit (8% - 1.0% 8% = 4.5% 5.5% 2.5% is the risk of assessing control risk too low. 4.5% sample rate plus 3.5% allowance for sampling error. is the actual sample deviation rate (9/200) is the expected deviation rate minus the computed upper = 5.5%) SOLUTIONS FOR EXERCISES AND PROBLEMS 20.59 Behavioral Decision Case: Determining the Best Evidence Representation This case is one of Bob Ashton's behavioral decision cases (Accounting Review, January, 1984, pp. 78-97. He give credit to W. Uecker and W. Kinney, "Judgment Evaluation of Sample Results: A Study of the Type and Severity of Errors Made by Practicing CPAs," Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 2, no. 3 (1977), pp. 269-75. The "answer" below is taken from Ashton. NOTE TO INSTRUCTOR: Take a look at this answer. You may want to get the students to discuss cases 1,2, and 3 first, then give them a chance to think about Cases 4 and 5. See if they can be fooled to change their minds to choose the larger samples for Cases 4 and 5, then discuss them. In this exercise, two pieces of information are available for each of the 498 three pairs of sample outcomes: (1) the sample size, and (2) the sample deviation rate. While sample size is independent of population parameters, sample deviation rate is representative of the population characteristic of interest, i.e. the population deviation rate. Use of the representativeness heuristic could cause one to ignore the size of the sample, and to base choices solely on the sample deviation rate. Thus one might choose Sample A in Case 1 and Sample B in Cases 2 and 3, because their sample deviation rates are lower. The calculation of achieved precision P=R/n show, however, that none of these three sample outcomes provides adequate assurance that the population deviation rate is below five percent, even at 90 percent confidence [10 percent risk of assessing control risk too low]. The other member of each pair (choices B,A,A) does provide the desired assurance at a 95 percent confidence level [5 percent risk of assessing control risk too low]. Thus reliance on the representativeness of the sample outcomes could lead one to choose the weaker evidence in these cases. Notice that the correct choice in Cases 1,2, and 3 is the larger sample. It might be tempting to conclude that this will always be true, i.e. that larger samples are always superior to smaller samples. But this simplification will not always work either. Consider Cases 4 and 5. The correct answers are the smaller samples. Interestingly, use of the representativeness heuristic (i.e. focusing on the smaller error rates) would lead to the correct choices in these two instances, but would result in incorrect choices in the first three pairs of sample outcomes. This illustrates that while use of simplifying heuristics can lead to good decisions, it can also lead the decision maker astray. 20.60 Behavioral Decision Case: Estimating a Frequency This case is one of Bob Ashton's behavioral decision cases (Accounting Review, January, 1984, pp. 78-97. He gives credit to M. Gibbins, "Human Inference, Heuristics and Auditors' Judgment Processes," Proceedings of the CICA Auditing Research Symposium, Laval University (1977). The answer below is taken from Ashton. The best answer to this exercise is the smaller department. This department processes only 15 invoices per day, while the larger department processes 45. The smaller department is more likely to have more days in which the number of invoices specifying discounts deviates from the average of 50 percent, since sampling variability is greater for small samples than for larger samples. [It takes only 9 invoices in the smaller department to exceed the 60 percent variation, while it takes 27 in the larger department.] People who use the representativeness heuristic, however, often do not consider the size of the sample, because the degree to which a sample statistic resembles the population does not depend on sample size. Consequently, the perceived likelihood of a sample statistic will be independent of sample size, and people may incorrectly choose "about the same" as the best answer. 20.61 Calculating Risk of Assessing Control Risk Too High The proper question is: What is the probability of finding 4 or more deviations in a sample of 80 when the actual rate in the population is exactly 4 percent? Use the Poisson approximation to calculate the probability of finding no 499 (zero) deviations, then 1 deviation, then 2, then 3. The sum of these probabilities is the probability of finding 3 or fewer. Thus the probability of finding 4 or more is 1 minus the sum. Look at the equation below. The term "np" is 80 x .04 = 3.2. The term "x" is 0, 1, 2, 3. P (0;3.2) = 0.0408 Probability of zero deviations in sample of 80 P (1;3.2) = 0.1305 Probability of one deviation in sample of 80 P (2;3.2) = 0.2088 P (3;3.2) = 0.2227 Probability of two deviations in sample of 80 Probability of three deviations in sample of 80 Sum = 0.6028 Probability of finding 3 or fewer when actual rate is 4 percent. 1 - Sum = 0.3972 Probability of finding 4 or more when the actual rate is 4 percent. The risk of assessing control risk too high is 39.72 percent. Using the Poisson approximation formula, the computed risk of finding zero deviation when the actual deviation rate in the population is 3 percent is: Computed risk:=x=0 2.718(80*.03)(80*0.03)0 = 0.091 0! The computerized risk probability of finding no deviations in a sample of 80 when the population deviation rate is 3 percent is 9.1 percent. Therefore, the probability is 1-9.1 percent = 90.9 percent of finding 1 or more deviations in a sample of 80 when the actual population deviation is 3 percent. Therefore, the auditor who assesses a higher control risk when one deviation is found is accepting a 90.9 percent risk of assessing the control risk too high. If the actual population rate were only 2 percent, the Poisson probability (computed risk) of finding zero deviations in a sample of 80 would be 20.2 percent. So the risk of assessing control risk too high would be 1-20.2 percent = 79.8 percent. Turning to the problem of controlling the risk of assessing control risk too high in the same example, suppose you decide to sample 140 units so finding 1 deviation could still give you UEL of 3 percent at 10 percent risk of assessing control risk too low. The Poisson probability of finding two or more deviations when the actual population deviation rate is less than 3 percent (say, 2 percent) is 0.7689, calculated as follows: 1. First calculate the probability (risk) of finding 0 and 1 deviations: Pp(0:140 x 0.02)=[2.718-2.8(2.8)0]/0! = 0.0608 Pp(1:140 x 0.02)=[2.718-2.8(2.8)1]/1! = 0.1703 Pp(x=0,1:140 x 0.02) = 0.2311 2. Calculate the probability (risk) of finding two or more deviations: Since the probability of finding zero or one is 0.2311, the probability of finding two or more is 0.7689 = 1-0.2311. Thus, the risk of assessing control risk too high when the actual population deviation rate is a little less than the tolerable rate is improved to 76.89 500 percent with a sample of 140, from the 79.8 percent risk with a sample of 80. The improvement is not much, but the example points out how a larger sample size reduces risk. Most attribute sampling tables contain probabilities calculated using the binomial equation. The binomial equation approximates fairly closely the hypergeometric equation which is mathematically accurate for finite populations and for sampling-without-replacement methods. The hypergeometric equation is even more difficult to solve than the binomial equation. The Poisson distribution approximates fairly closely the binomial distribution, and it is easier to calculate using a pocket calculator capable of raising numbers to a power. Auditors can use the equation shown below to calculate risk because the Poisson distribution is a limiting case of the binomial distribution when the population is large and the deviation rate is low (commonly found in audit situations). Note: Even if the deviation rate is high the Poisson distribution provides a conservative (i.e. overestimates) the actual deviation rate. Pp(x;np)= e-np(np)x X! where: Pp(x;np)=Poisson probability of finding exactly x number of deviations in a sample having np expected number of deviations e= Base of natural logarithms, approximately 2.718 n= Sample size p= Hypothesized deviations rate x= Number of deviations The computed risk of finding a given number of deviations is a cumulative function: Computed risk = x e-np(np)x x! For example, consider the illustration in Chapter 20 concerning the risk of assessing control risk too high. When the procedure of vouching a random sample of 80 invoices to supporting shipping orders was performed, the auditor found no deviations (no cases of missing shipping orders). The example says the probability (risk) is 10 percent that the actual population deviation rate is equal to or greater 20.62 Sample Size Relationships a. Tolerable deviation rate = 0.05 Expected population deviation rate = zero. Sample Size Risk of Assessing Control Risk Too Low 0.01 0.05 0.10 b. Population > 1,000 93 60 47 Population = 500 76 54 45 Acceptable risk of assessing control risk too low = 0.10 (BETA RISK) Expected population deviation rate = 0.01 501 Sample Size Tolerable Dev. Rate Population > 1,000 0.10 0.08 0.05 0.03 0.02 c. Population = 500 26 33 58 116 231 25 31 52 95 159 Acceptable risk of assessing control risk too low = 0.10 (BETA RISK) Tolerable deviation rate = 0.10 Sample Size Expected Population Deviation Rate Population > 1,000 0.01 0.02 0.04 0.07 0.09 d. Population = 500 26 29 39 77 231 25 28 37 68 159 The population size-adjusted sample sizes are figured using the formula n = n' 1 + (n' /N) where n' is the sample size in using Appendix 20A and R=NP N = 500 population size n = sample size adjusted for population size 20.63 Exercises in Sample Selection a. The first 5 usable numbers (using the path down the column and then to the top of next column) are: 1609, 3342, 2287, 3542, and 1421. Note that 14 numbers were reviewed to get 5, and 9 were discarded. b. The first 5 usable five-digit numbers (using the path down the column and then to top of next column) are: 02921, 05303, 08845, 05851, and 09531. Note that 26 numbers were reviewed to get 5, and 21 five-digit numbers were discards. This selection can be made more efficient by converting the random number to 4 digits to correspond with the number of digits in the population size. There will be fewer discards if you subtract 2220 from the beginning and ending numbers and use the sequence 0000 to 9099. Using the first 4 digits and starting at the same place: Random numbers Add back 2220 2041 + 2220 = 2870 + 2220 = 7457 + 2220 = 6261 + 2220 = 7568 + 2220 = Random check number 4261 5099 9677 8481 9788 This method is random and there was only one discard to get 5 usable numbers. 502 c. 1. 2. 3. d. Choosing a month at random does not generate a random sample of the year's vouchers. This is a type of block sample and is not acceptable for statistical validity (but may be acceptable for judgmental sample). Random 7-digit numbers would generate a random sample, but there would be a large number of discards. This method is not efficient. Ten vouchers from each month is an acceptable choice if and only if an equal number of vouchers were recorded each month. This method can be modified by calculating the relative number of vouchers each month and selecting that proportion of the vouchers from that month. For example, if 4,520 vouchers (10%) were issued in January, then select 12 sample vouchers (10% of 120) from January. In case (a), select every 100th sales invoice (5,000/50 = 100) starting with number 1609. The next four numbers are 1709, 1809, 1909, 2009. The selection may also be made by starting at the front of the file with a random number between 1 and 100, then selecting every 100th item. In case (b), select every 91st check (9,100/100 = 91) starting with number 02921. The next four are 03012, 03103, 03194, 03285. As in case (a) other random starts are possible. In case (c), select every 376th voucher (45,200/120 = 376) starting with number 03-01102. The second number is 03-01478. Successive numbers may spill over into the April file. The auditor has had to count to the end and then continue the count in succeeding months. 20.64 Imagination in Sample Selection a. Sample from Checking Accounts with Overlapping Numbers * Let checks in Account #2 be represented by the check numbers 0001 6000 (6,000 checks). * Let checks in Account #1 be represented by numbers 6001 - 9000 (obtained by adding the constant 2368 to the actual numbering sequence of 3633 - 6632). The new sequence contains 3,000 numbers, the same as the original number of checks. * When a 4-digit random number between 0001 and 6000 is selected, it identifies a check in Account #2. * When a 4-digit random number between 6001 and 9000 is selected, subtract the constant 2368, and the remainder identifies a check in Account #1. * Random numbers 9001 - 9999 are discards. * Starting in Appendix 20B, row 1, column 2: Check Selected in b. Random Number Discard or Constant 9541 9985 6815 2543 5190 1925 0030 Discard Discard -2368 NA NA NA NA Account #1 Account #2 4447 2543 5190 1925 0030 Sample of Purchase Orders * First convert of 5-digit real sequence (09000 - 13999) to the 4digit sequence 000 - 4999 by subtracting the constant 09000. 503 Then let the sequence of numbers from 5000 - 9999 also represent purchase orders in the sequence. Now all the 4-digit random numbers represent purchase orders, and none will be discards. You will, however, need to convert each 4-digit random number into a purchase order number. Starting in Appendix 13-A, row 30, column 3: * * * * Random Number Conversion for 5000 - 9999 4251 8991 5077 9431 5595 - Conversion to P.O. Sequence NA 5000 5000 5000 5000 + + + + + 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 Purchase Order No. 13251 12991 09077 13431 09595 Note: When sampling without replacement, some numbers will be discards when two of them identify the same purchase order. For example, random numbers 4251 and 9251 both identify purchase order 13251. c. d. Sample of Perpetual Inventory Records Systematic sampling is probably the most efficient method. You know the list has 3740 item descriptions (74 x 50 + 40). The factor k = 37.4. Take 5 random starts by entering a random number table and choosing a 2-digit random number between 1 and 75 to represent a page, choosing the next 2digit random number to represent a line, then selecting every 187th description (187 = 5 x 37.4). Repeat the procedure five times. For example, start in Appendix 13-A, row 1, column 1: Page Line 1st item 32 59 65 14 28 07 46 35 20 02 p. p. p. p. p. 32, 59, 65, 14, 28, 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 7 46 35 20 02 2nd item 3rd item... 20th item p. 35, 1. 44 p. 63, 1. 32 p. 69, 1. 22 p. 39, 1. 31 p. 67, 1. 19 p. 73, 1. 9 Sample of Physical Inventory The physical selection might involve problems not covered in the exercise--separate selection of high-value items, the physical size of items. This solution is simplistic for ignoring these potential complications. The inventory physical frame is 3-dimensional. It has width (300 rows of shelves), length (75 feet each row) and height (10 tiers in each row of shelves). Two ways to select the sample are: 1. Think of the layout as 22,500 linear feet of shelf rows (300 x 75). Using systematic sampling, take 5 random starts, each time pacing off 1,125 feet (5 x 22,500/100) in a pre-determined path around the warehouse. At each stop, select a random number between 1 and 10 to identify the tier, and select that item. 2. Think of the layout as 300 2-dimensional coordinates. Select 100 of the rows, but be careful about any systematic selection because physical storage may be in some nonrandom pattern. For each selected row, select a random number between 1 and 75 to locate a position on 504 the row. Then select a random number between 1 and 10 to identify a tier and the inventory at that location. 20.65 Cases a, b, c: Illustrate effect of different risks of assessing control risk too low. Cases d, e, f: Illustrate effect of larger samples with same sample deviation rate. Cases g, h, i: Illustrate different sample deviation rates. (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) (g) (h) (i) Actual sample deviation rate 2% 2% 2% 2% 2% 2% 10% 6% 0 Computed upper limit (approx.) 5% 4% 12% 3% 3.6% 6.3% 4.6% 3.6% 17% 20.66 Discovery of Sampling Calculations Critical rate of occurrence Required reliability Sample size (minimum) (a) (b) (f) (g) (h) (i) .4% .5% 1.0% 2.0% 1.0% .5% .4% .4% .4% 99 (c) 99 1,000 900 (d) (e) 99 99 91 70 70 85 95 460 240 240 240 300 460 700 SOLUTIONS FOR DISCUSSION CASES 20.67 Mistakes in Sampling Application Mistake Explanation 1. The statistical criteria call for a sample of 160, not 100. 1. He apparently read Appendix 13-B.2 for the 1% expected rate instead of for 2%. 2. He used two test months. 2. Even a selection of two months does not make the sample representative of the year's population. 3. He stratified the population, but did not adjust the total sample size accordingly. 3. Nothing is wrong with stratification, but in this case the sample size in each stratum would be about 160. 4. He apparently did not define the error attribute carefully before starting the audit work. 4. Indicated by his after-the-fact rationalization of the two errors into non-errors. In fact the pay rate error has dollar-value impact that he made no effort to recognize (i.e.), liability for underpayment of wages). He did not follow up sufficiently on the errors that he did find. 5. He improperly combined a stratified 5. When stratification is done 505 sample into a single evaluation. properly, the two samples should be evaluated independently. 6. The reviewers (senior and partner) were not competent to review the statistical application. 6. This is not Tom's mistake, but it's worthwhile to point out that competence is as necessary at the review level as it is at the operational level. 20.68 Determine a Test of Controls Sample Size Test of controls sample size = 75, with plan to assess control risk = .10 and audit minimum (25) substantive balance-audit sample. This choice gives the lowest total cost if control risk is actually assessed at .10. EXHIBIT 20.B-1 GOODWIN MANUFACTURING COMPANY Test of Control Balance-Audit Control Risk Categories Low control risk Moderate control risk Control risk below maximum Maximum risk CR TDR RIA RACRTL .10 .20 .30 .40 .50 .60 .70 .80 .90 1.00 .04 .06 .08 .10 .12 .14 .16 .18 .20 .22 .50 .28 .19 .14 .11 .09 .08 .07 .06 .06 .05 .09 .15 .25 .40 .50 .50 .50 .50 .50 n[c] 75 40 24 14 8 5 4 4 4 3 Cost $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 900 480 288 168 96 60 48 48 48 36 n[s] 25 46 60 71 80 87 91 96 101 101 Cost $ 625 $1,150 $1,500 $1,775 $2,000 $2,175 $2,275 $2,400 $2,525 $2,525 TOTAL $1,525 $1,630 $1,788 $1,943 $2,096 $2,235 $2,323 $2,448 $2,573 $2,561 Audit risk = .05 Inherent risk = 1.0 Analytical procedures risk = .90 [detection probability = .10] RIA = (AR=.05)/[(IR=1.0) x CR x (AP=.90)] Anchor TDR = 7 x 2,000,000 = .03 for CR = .05 467,000,000 RACRTL = .02 for each RIA for each CR RIA - .06 SOLUTIONS FOR KINGSTON CASE 20.69 Kingston Company: Dollar-Unit Sampling Audit of Accounts Receivable Even though the requirements are intended to guide students through the steps, there are several ways to go wrong in this DUS problem. a. The first way to go wrong is in deriving the risk of incorrect acceptance (RIA). If they miss this, nothing else will correspond to the solutions below. The 506 auditors said they would set audit risk at 0.05 and that control risk and inherent risk were jointly assessed at 0.30. About the analytical procedures, they said: "Too bad we can't say analytical procedures reduce out audit risk." RIA = AR = .05 = 0.166667 (round to 0.17) (IR=1.0) x (CR=0.30) x (AP=1.0) b. Deciding how many errors to estimate for using the Poisson risk factor method calculation of the DUS sample size is not specified in the dialogue. Students have to remember to calculate a ratio of expected error ($4,000 stated in the dialogue) to the balance under audit ($300,000, and they might mistakenly use the $400,000 total). This ratio (4,000/300,000) is 1.33 percent, which suggests a number of deviations of more than one but less than 2. The sample sizes can be different: Based on one error Based on two errors n = 300,000 x 3.21 = 96 n = 300,000 x 4.53 = 136 10,000 10,000 The solutions below assume that the same 10 errors were found, no matter the sample size. c. Calculate the projected likely error and the upper error limit based on the errors in the sample. Another place to go wrong with "nonsampling error"--calculating the tainting percentages. Here are the correct taints. Exhibit 14.24-1: ERRORS DISCOVERED IN THE SAMPLE OF ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE ACCT # 25 366 465 623 741* 741* 774 1206 1352 1466 * d. BOOK WRONG WRONG BALANCE QUANT'Y MATH $503 $492 $507 $195 $3,698 $3,698 $517 $524 $700 $351 WRONG AUDITED DATE AMOUNT $115 $112 $136 $63 $100 $100 $140 $119 $400 $59 $388 $380 $371 $132 $3,598 $3,598 $377 $405 $300 $292 ERROR TAINT 22.86% 22.76% 26.82% 32.31% 2.70% 2.70% 27.08% 22.71% 57.14% 16.81% Selected twice for two dollar units. Decide whether to "accept" the recorded amount without adjustment or to "reject" the recorded amount as an accurate balance with respect to the tolerable misstatement the auditors will allow. When students use the UEL decision rule, the decision is a "rejection" with sample sizes of 96 and 136. In both cases, the upper error limit is greater than the $10,000 tolerable misstatement. 507 DOLLAR-UNIT SAMPLING UEL CALCULATION Population recorded amount $300,000 Risk incorrect acceptance 0.17 Estimated number errors 1 Sample size 96 1. Basic 2. Projected likely error First Second Third Fourth Fifth Sixth Seventh Eighth Ninth Tenth UEL,PGW TAINT ASI 1.77 100.00% $3,125 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 57.14% 32.31% 27.08% 26.82% 22.86% 22.76% 22.71% 16.81% 2.70% 2.70% $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 DOLLAR AMOUNT $5,531 $1,786 $1,010 $846 $838 $714 $711 $710 $525 $84 $84 Projected likely error 3. Precision gap widening First Second Third Fourth Fifth Sixth Seventh Eighth Ninth Tenth $7,308 0.44 0.32 0.27 0.23 0.21 0.19 0.18 0.17 0.15 0.15 57.14% 32.31% 27.08% 26.82% 22.86% 22.76% 22.71% 16.81% 2.70% 2.70% $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $3,125 $786 $323 $228 $193 $150 $135 $128 $89 $13 $13 $2,058 Upper Error Limit at risk 0.17 of incorrect acceptance $14,897 DOLLAR-UNIT SAMPLING UEL CALCULATION Population recorded amount $300,000 Risk incorrect acceptance 0.17 Estimated number errors 1 Sample size 136 1. Basic 2. Projected likely error First Second Third Fourth Fifth Sixth Seventh Eighth Ninth Tenth UEL,PGW TAINT ASI 1.77 100.00% $2,206 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 57.14% 32.31% 27.08% 26.82% 22.86% 22.76% 22.71% 16.81% 2.70% 2.70% $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 DOLLAR AMOUNT $3,905 $1,261 $713 $597 $592 $504 $502 $501 $371 $60 $60 508 Projected likely error 3. Precision gap widening First Second Third Fourth Fifth Sixth Seventh Eighth Ninth Tenth $5,161 0.44 0.32 0.27 0.23 0.21 0.19 0.18 0.17 0.15 0.15 57.14% 32.31% 27.08% 26.82% 22.86% 22.76% 22.71% 16.81% 2.70% 2.70% $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $2,206 $555 $228 $161 $136 $106 $95 $90 $63 $9 $9 $1,452 Upper Error Limit at risk 0.17 of incorrect acceptance $10,518 20.70 Kingston Company: Determine the Amount of a Recommended Adjustment--DollarUnit Sampling The alternative (a) requirement gives the results of the evaluation of a sample of 96 dollar units from assignment 14.24. Thus the adjusting journal entry for the alternative and for 14.24 with a sample of 96 should be identical. The 65% cost of goods sold hint comes into play in the adjustment of the sales recorded with the wrong date (Goods shipped in January should not have been recorded in the year under audit. When these are adjusted, the cost of goods sold should be reversed and put back into inventory.) Students must be careful to include the results of auditing the six large accounts. These errors are not subject to sampling error. For instructors' information, the actual population has about $15,000 overstatement error in it. (Refer to the Kingston story at the beginning of this instructors' manual.) An adjustment keyed on the rather small amount of actual (known) error will be too small. The adjustment given below is based on the projected likely error amounts, adding the errors found in the six large accounts. Debit Sales (Returns and Allowances) $2,448 Accounts Receivable Adjust for the wrong quantities billed. Sales (Returns and Allowances) Accounts Receivable Adjust for the arithmetic errors. Credit $2,448 $ 618 Sales $5,292 Inventory (65%) $3,440 Accounts Receivable Cost of Goods Sold Adjust to reverse the sales recorded too early and restore the cost of goods sold to inventory. $ 618 $5,292 $3,440 509 If these entries are based on students' audit of a sample of 136 in assignment 14.24, the DUS calculations are as follows: ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE DUS CALCULATIONS: Sample = 136 Type of Error Wrong Quantity: Six large accounts Sampled accounts Known Error Upper Error Limit 600 199 $ 1,305 $ 5,713 600 199 $ 1,305 $ 5,713 Wrong Arithmetic: Six large accounts Sampled accounts 450 100 $ 120 $ 4,070 Wrong Date: Sampled accounts 945 $ 3,736 $ 8,813 1,050 1,244 $ 5,161 $10,518 Wrong Quantity: Six large accounts Sampled accounts All Error: Six large accounts Sampled accounts $ Projected Likely Error $ The adjusting entries based on these data are: Debit Sales (Returns and Allowances) $1,905 Accounts Receivable Adjust for the wrong quantities billed. Sales (Returns and Allowances) $ 570 Accounts Receivable Adjust for the arithmetic errors. Sales $3,736 Inventory (65%) $2,428 Accounts Receivable Cost of Goods Sold Adjust to reverse the sales recorded Credit $1,905 $ 570 $3,736 $2,428 510 too early and restore the cost of goods sold to inventory PART II SOLUTIONS FOR MULTIPLE-CHOICE QUESTIONS 20.71 a. b. c. d. Correct. Incorrect. Incorrect. Incorrect. 0.015/(0.50 x 0.30 x 0.50) = 0.20 see a. see a. Illogical to have a "risk" greater than 1.00 see a. 20.72 a. b. c. d. Incorrect. Incorrect. Incorrect. Correct. see d. not the "best answer" see d. not the "best answer" see d. not the "best answer" They are all audit judgments. TD is a product of the other judgments. 20.73 a. b. Incorrect. Incorrect. c. d. Correct. Incorrect. Efficiency is considered less important than effectiveness. This is an explanation of how incorrect rejection is overcome, producing more work than was necessary. Effectiveness is considered more important than efficiency. (This is the throwaway!) The evidence may be sufficient and competent, but the decision can still be wrong. 20.74 a. b. c. d. Incorrect. Correct. Incorrect. Incorrect. This is "underauditing." "Overauditing" is doing too much work. "Taking more risk" implies doing too little work. This is a definition of audit risk at the overall level. 20.75 a. b. c. Correct. Correct. Incorrect. d. Incorrect. DUS does not require a variability estimate. DUS uses the statistics of the binomial distribution. In DUS the logical unit is audited, same as in classical sampling. Both methods utilize calculation of an upper error limit in analyses of results. 20.76 a. b. c. d. Incorrect. Incorrect. Incorrect. Correct. DUS samples are random. DUS is "sampling with replacement." DUS auditors do not ignore the risk of incorrect acceptance. The population is defined as $1 units and not as the number of logical units in the population. 20.77 a. b. c. d. Incorrect. Incorrect. Incorrect. Correct. Auditors must specify audit risk. Auditors must assign tolerable misstatement. Auditors must estimate the misstatement. An estimate of standard deviation is not needed for DUS. 20.78 RIA a. b. c. d. 20.79 a. Correct Correct. 0.03 0.03 0.06 0.10 Errors 2 1 0 2 Recorded Amount $1,000,000 $1,000,000 $1,500,000 $1,500,000 Tolerable Misstatement $ $ $ $ 50,000 35,000 65,000 65,000 Sample Size 140 153 65 123 The risk of incorrect acceptance must be specified for sample size calculation and quantitative evaluation of monetary error evidence. 511 b. Incorrect. c. Incorrect. d. Incorrect. 20.80 a. Incorrect. b. Correct. c. Incorrect. d. Incorrect. The opposite is true: Smaller logical units have a lesser probability of selection in the sample than larger units. The systematic sampling "skip interval" illustrated in the text is derived by dividing by n-1, while the "average sampling interval" is derived by dividing by n. Projected likely misstatement can be calculated in the quantitative evaluation when one or more errors are discovered. DUS sampling loads the sample with high-value sampling units, and they are more likely to be overstated than understated. The sample selection automatically achieves high-dollar selection and stratification. The sample selection is biased against including a representative number of small-value population units. Expanding the sample for additional evidence is not very easy. 20.81 Selecting a Dollar-Unit Sample The solution starts by finding the recorded amount of the total = $38,610. The skip interval is 38,610 / 10 = 3,861. "Random start" at 1,210. Whitney Company Inventory Sample Selection Sept 30, 20XX Index_____ Account Number Account Balance Modified Accumulator Accumulator 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 1,750 1,492 994 629 2,272 1,163 1,255 3,761 1,956 1,393 884 729 937 5,938 - 1,210 2,561 306 323 - 1,266 103 1,152 1,052 853 540 - 2,437 - 1,708 771 5,167 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 2,001 222 1,738 1,228 2,577 1,126 565 2,319 1,681 - 554 332 1,406 1,227 1,350 1,385 820 1,499 681 Dollar Selected Logical Unit - 1.300 1st 3,862nd 1,210 1,492 - 3,538 7,723rd 629 - 2,709 - 2,809 11,584th 15,445th 1,255 3,761 - 3,321 19,306th 1,393 1,306 - 2,555 23,167* 27,028* 5,938 - 2,455 30,889th 1,738 - 2,511 34,750th 2,577 - 2,362 38,611th 2,319 38,610 * Two dollar units in the same logical unit. Total of logical units in the Prepared by___Date___ Reviewed by___Date___ 512 sample of 10 dollar units 22,312 20.82 When RIA is greater than .5 one has to question the usefulness of the particular statistical test. The risk model yields even more problematic treasures if IR x CR x AP is less than or equal to AR. This makes RIA equal to or greater than 1 (i.e. RIA is more than 100% !) when RIA = AR/(IR x CR x AP). The model, therefore, suggests that tests of details may not be necessary. All the evidence thus rests on internal control, inherent risk (the subjective probability estimate of misstatement getting into the accounting in the first place), and the effectiveness of analytical procedures. Auditing theory and practice maintains that some effective substantive procedures should be performed--perhaps including a minimum sample size for tests of details in addition to substantive analytical procedures. SOLUTIONS FOR DISCUSSION CASES 20.83 Relation of Dollar-Unit Sample Sizes to Audit Risk Model CONTROL RISK INFLUENCE ON SUBSTANTIVE BALANCE-AUDIT SAMPLE SIZE AR = .05 IR = 1.00 AP = 1.00 (CR) .10 .20 .30 .40 .50 .60 .70 .80 .90 1.00 RIA 0.50 0.25 0.167 0.125 0.10 0.083 0.071 0.0625 0.0556 0.05 AR = .10 IR = 1.00 AP = 1.00 AR = .05 IR = .50 AP = 1.00 AR = .05 IR = 1.00 AP = .50 n(s) RIA n(s) RIA n(s) RIA n(s) 21 42 53 61 69 76 80 84 87 90 .50 .50 .33 .25 .20 .17 .14 .13 .11 .10 21 21 33 42 48 53 59 61 66 69 .50 .50 .33 .25 .20 .17 .14 .13 .11 .10 21 21 33 42 48 53 59 61 66 69 .50 .50 .33 .25 .20 .17 .14 .13 .11 .10 21 21 33 42 48 53 59 61 66 69 Discussion: Comparing the first two sets at left: Larger audit risk produces smaller samples throughout the entire range of control risks. Comparing the three sets at the right: Doubling the audit risk from .05 to .10 has the same effect on RIA and sample size as assessing half the IR or AP. Comparing the two sets at the left: The same change in IR and AP have the same effect on RIA and sample size. 20.84 Determining an Efficient Risk of Incorrect Rejection (DUS) For each of the control risk levels, calculate the expected cost savings from auditing the initial alternative (minimum) sample. Assume that the action in the event of a rejection decision is to expand the work by selecting additional units up to the number in the base sample. Control Risk 0.20 "Base" Sample Alternative RIR Alternative (Minimum) Sample 80 .02 41 Cost Savings $8(nb-na)-$19(nb-na)(RIRa-.01) $312 - $ 7 = $305 513 0.30 96 .02 53 $344 - $10 = $334 0.40 107 .03 62 $360 - $17 = $343 0.50 116 .03 68 $384 - $18 = $366 0.60 122 .03 74 $384 - $18 = $366 0.70 128 .03 78 $400 - $19 = $381 0.80 133 .03 82 $408 - $19 = $389 0.90 137 .03 86 $408 - $19 = $389 1.00 141 .03 89 $416 - $20 = $396 Discuss the potential audit efficiencies and possible inefficiencies from beginning the audit work with the alternative (minimum) sample size. The potential audit efficiency is achieving the cost savings scheduled above. Depending on the control risk level planned for assessment, the savings could range from $305 to $396. The large savings arise from the very small increase in RIR for the alternative (minimum) sample sizes. These sample sizes were obtained by a method that is fairly insensitive to RIR changes. The alternative sample sizes are actually minimum samples that also fit the criterion of alternative RIR from .02 and .03 to .50. In other words, in this attribute-type dollar-unit sample, the alternative sample sizes are the minimum sample sizes, no matter what RIR greater than .02 and .03 are specified. (Note to instructors: I am not sure that very many students, except the mathematicians, will be interested in this phenomenon.) 20.84(c) The solutions for different sample sizes will be similar in form, although the numbers will be different. 20.85 Comparison of Sampling Methods 20.85(a) Unrestricted random sample of 10 accounts RANDOM UNIT SAMPLE ACCT # 2 5 7 14 20 28 32 35 42 46 Number Total Average Std Dev Ratio BALANCE $346 $1,555 $1,906 $178 $141 $193 $503 $157 $91 $156 10 $5,226 $522.60 $619.56 WRONG QUANT'Y WRONG MATH WRONG DATE $600 $200 $11 $115 1 $200 1 $11 2 $715 20.85(b) Systematic random selection of 10 accounts SYSTEMATIC RANDOM SAMPLE MONETARY ERROR AUDIT AMOUNT $0 $600 $200 $0 $0 $11 $115 $0 $0 $0 $346 $955 $1,706 $178 $141 $182 $388 $157 $91 $156 $926 $92.60 $181.00 0.177190 $4,300 $430.00 $488.43 514 ACCT # BALANCE 3 5 3 15 23 25 $1,301 $1,555 $320 $188 $145 $461 33 35 43 45 $500 $157 $65 $470 Number Total Average Std Dev Ratio 10 $5,162 $516.20 $481.36 WRONG QUANT'Y WRONG MATH WRONG DATE $600 $111 $107 $117 1 $111 0 $0 3 $824 MONETARY ERROR AUDIT AMOUNT $0 $600 $0 $0 $0 $111 $1,301 $955 $320 $188 $145 $350 $107 $0 $0 $117 $393 $157 $65 $353 $935 $93.50 $176.08 0.181131 $4,227 $422.70 $375.11 20.85(c) Systematic random dollar-unit selection of 10 dollars SYSTEMATIC DOLLAR-UNIT SAMPLE ACCT # 3 3 5 7 15 23 28 36 45 50 Number Total Average BALANCE $1,301 $1,301 $1,555 $1,906 $188 $145 $193 $388 $470 $268 10 $6,414 $641.40 WRONG QUANT'Y WRONG MATH WRONG DATE $600 $200 11 $117 1 $200 1 $11 2 $717 MONETARY ERROR AUDIT AMOUNT $0 $0 $600 $200 $0 $0 $11 $0 $117 $0 $1,301 $1,301 $955 $1,706 188 $145 $182 $388 $353 $268 $928 $92.80 $5,486 $548.60 TAINTS 0.00% 0.00% 38.59% 10.49% 0.00% 0.00% 5.70% 0.00% 24.89% 0.00% 20.85(d) With a sample of 10, the average sampling interval is $1,752. Account number 7, with a balance of $1,906, will always be included in a dollarunit sample of 10. 20.85(e) Table comparing sampling methods TABLE COMPARING RESULTS OF SAMPLES Population size Recorded total Sample size Random Unit Sample Systematic Unit Sample Dollar Unit Sample 50 $17,523.00 10 50 $17,523.00 10 $17,523.00 $17,523.00 10 515 Recorded amount in sample $5,226.00 Number of error accounts in sample 4 Monetary misstatement in sample $926.00 $5,162.00 $6,414.00 4 4 $935.00 $928.00 $92.60 $93.50 N/A Error ratio 0.1772 Projected misstatement Difference method $4,630.00 Ratio method $3,105.00 Upper error limit at 2.0 % risk of incorrect acceptance Z(B) = 2.05 (Difference method) $9,930.50 0.1811 N/A $1,396.00 Average misstatement in sample $4,675.00 $3,173.00 $9,975.50 $9,322.00 20.85(f) Calculation of upper error limit Dollar-Unit Projected Misstatement Factor Taint Sampling Interval Projected Error Basic error 3.91 100.00% $1,752 $ 6,850 First error Second error Third error Fourth error 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 38.59% 24.89% 10.49% 5.70% $1,752 $1,752 $1,752 $1,752 $ Projected error Gap Widening: First error Second error Third error Fourth error 676 436 184 100 $ 1,396 0.92 0.69 0.56 0.50 38.59% 24.89% 10.49% 5.70% $1,752 $1,752 $1,752 $1,752 Upper error limit (.02 risk of incorrect acceptance) $ 622 301 103 50 $ 9,322