Summary of Physical and Psychological Safety for Work wi

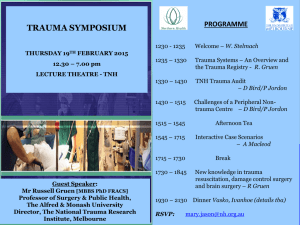

advertisement

Summary of Physical and Psychological Safety for Work with Trauma Survivors This paper presents recommendations that should raise awareness among staff about how to protect project and research participants who have been victims of violence or other trauma. The concerns are to minimize their risk of both physical and psychological harm. Physical Safety: 1. Discussion of certain topics, such as gender-based violence, child abuse, informal economic activities, political activities, household wealth, sexuality, HIV/AIDS, religion or police activity can place individual at risk of physical harm in some settings. 2. Populations who have been traumatized and might face harm if they participate in research or projects include commercial sex workers, adolescent girls, ethnically marginalized groups, women in refugee camps, and women in general. It is important to discuss these risks with them in advance and make every effort to ensure their safety through confidentiality protocols and other means. 3. It is critical to balance effective techniques for eliciting information about trauma with safety risks. Some research approaches such as community mapping, body mapping, genograms, pile sorts, and art or media-based research tools should be carefully investigated in advance as to potential concerns about safety to participants, and methods of decreasing risk, such as focus group commitment to confidentiality or tailoring different points of discussion to different groups. 4. The location of project work or research on sensitive issues should be private and far from any perpetrators of violence. 5. Safety-screening questions should be asked of participants during the session to assess risk of violence after their participation. 6. Safety plans should be developed with all vulnerable participants. Through discussions, women can be made aware of strategies others have used to ensure their safety, and where they can go for help if needed. Psychological Safety: 1. Researchers need to be able to recognize symptoms of retraumatization or reexperiencing the trauma during interviews, such as distress, anxiety, agitation, flashbacks and dissociation. 2. Researchers should talk to participants about the risk of retraumatization before starting the session and develop signals to stop the discussion if it should occur. Interactions with the participants should be conducted in a manner that maximizes comfort and empathy. 3. If dissociation or flashbacks occur during the sessions, researchers can use a process called ‘grounding’, in which they state the participant’s name and location, tell them they are okay, and ask them to touch nearby objects in the room. Another approach is to distract the participants by looking out the window or turning on a radio. 4. Screen participants for risk of suicide and homicide during the session. 5. Conclude the session by focusing on the participant’s strengths in dealing with the trauma, discussing possible coping strategies or referral information for professional help. 6. Staff should be trained to recognize secondary retraumatization among themselves and their co-workers, i.e., the experience of traumatic symptoms because of their involvement with traumatized persons. The risk of secondary retraumatization increases through disclosing personal information or sharing personal experiences with victims, although this can be mitigated through regular staff debriefings and supportive discussions. Psychological and physical safety risks are inherent to working with survivors of trauma, but those risks can be minimized through careful planning and monitoring. Appendices A. Supporting Infrastructure: security, emotional support, physical health, legal aid, economic and living support, and support for staff. B. Protocol for Breached Security or Confidentiality C. Safety Screening Questions D. Developing a Safety Plan E. Psychiatric Diagnoses Associated with Trauma F. Techniques to Reduce Traumatization G. Screening for Suicide and Homicide