The Aesthetic Ecology of a Gesture

advertisement

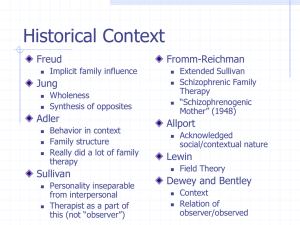

The Aesthetic Ecology of a Gesture Katharine Young In this study I examine gestures with respect to problems of interiority and mimesis. I take interiority to be the relationship of the gesture to an internal ecology, by which I do not mean an anatomy of the body but an embodied experience of meaning, meaning as meaning for me. I take mimesis to be the relationship between the gesture and an external ecology, in this instance to the occasion on which it was made, which is to say meaning as meaning for the other. By extension, this is a relationship between the gesture and its world. And I shall argue that in the end, these two ecologies are not discontinuous. So aesthetics, as it were, sweeps all the way through body and world as one, again as it were, gesture. Interiority The skin encloses an interior and exposes an exterior. Its surface remains sensitive on both sides: the outside to environmental stimulation, the inside to interior excitements. But the relationship between exteroception and the persistent features of the external world has no correlate in interoception, whose features, as it were, come into being only for a singular perceiver. Perceptual information from within, of the sort Drew Leder calls “visceral sensation” (1990), attests only to the interiority of its perceiver. I do not experience vestibular disequilibrium, for instance, as the world tilting but as feeling dizzy. Hence, the bodily interior offers itself as private space: what happens inside it is concealed from other people but perceptible to the person inside whom it is. In philosophy, the problem of the ontological status of things of which I am aware but other people are not aware, and of which they are not able to be aware, takes the form of the problem of other minds. Descartes argued that it is only of such interior things that I can be certain, and only of some of those, namely, the ones he called thought things, res cogitans. By these he meant, ideas of things and not the things themselves. Of things extended in the world, res extensa, Descartes thought I could not be certain, because my sensory perceptions apprehended only attributes, properties of things, not essences – that by which a thing is what it is – and because such perceptions were in any case notoriously fallible (Meditation). In this strange cleavage, the body fell on the side of extended things; thoughts fell on the side of unextended things but inside the body. Hence, the interior of the body came to be regarded as the space of thought and at the same time thought came to be regarded as taking up no space. Out of our cultural history of Cartesian metaphysics, we have fabricated mind and body as incommensurable substances, the one interiorized in the other. Thus we have concocted the myth of depth, our curious persuasion that we are in there, partially hidden, even from ourselves, inaccessible except to introspection. But if the self is within, who introspects? A second subject would have to be extruded to introspect the first, and a third for that one, and so on in an infinite regress. Depth psychologies participate in this paradox; surface psychologies – behavioral psychologies, for instance – eschew it. Sigmund Freud, for instance, argued that not only are thoughts and emotions concealed from others in the body but they are also for the most part also concealed from the person who has them, a double concealment that has mystified philosophy. Freud writes, “at any given moment consciousness includes only a small content, so that the greater part of what we call conscious knowledge must in any case be for very considerable periods of time in a state of latency, that is to say, of being psychically unconscious” (The Unconscious, in C&S 1984:187). It is as a consequence of these unconscious thoughts and emotions that “ideas...come to us we do not know from where, and...intellectual conclusions [are] arrived at we do not know how” (C&S 187). It is not just that we have a consciousness within, we also have an unconscious, as if, as Drew Leder puts it (1990), there were a second consciousness hidden from the first. Young – 2 On account of our skepticism about the trope of interiority, modern philosophy has reversed Descartes’ privilege. Surely it is only of external things, attested to by other perceivers, that I can be certain. Of the contents of my own mind, I ought to be skeptical; of the contents of other minds, I can know nothing at all. If, this reasoning goes, the self, its thoughts, its emotions, are concealed in the body like a black box, then how could I ever know what other people think and feel? We are heir to the behaviorist anxiety about interiority. In The Concept of Mind (1949), Gilbert Ryle writes, “Emotions are described as turbulences in the stream of consciousness, the owner of which cannot help directly registering them; to external witness they are, in consequence, necessarily occult. They are occurrences which take place not in the public, physical world but in your or my secret, mental world." Persons could only retrieve such phenomena by introspection, to which others are not privy. In the social sciences, a profound distrust of the trope of interiority resulted in behaviorism: the observation of behavior, acts, and words, as signs of the self. Lila Abu-Lughod and Catherine Lutz argue, for instance, that once emotion is interiorized, it is at once essentialized and naturalized, and so put beyond both social construction and anthropological analysis (1993). Their suspicion is that interiority is a trope, as if the body were being proposed as the container of the mind, thereby instantiating mind/body dualism, along with private languages, inner selves, and other suspect entities. There couldn’t possibly be any sort of self inside itself, or if there is, nobody but the person who has it could possibly get access to it. All we can properly go by, the behaviorists suppose, is external behavior, about whose relationship to inner states it would be improper for us to speculate. Ryle made no speculations about inner states. Influenced by Wittgenstein, he became more interested in how words are used than in what they mean. To understand anger, he wrote, look at the "conditions under which it is appropriate and meaningful to say someone is angry." Ryle notes that this picture of mind “resulted in the creation of numerous philosophical pseudo-problems, for example, the problem of determining whether other minds exist and of even knowing what others are thinking or feeling” (Calhoun and Solomon 1984: 261). Ryle accepted the criteria of behaviorism and solved the problem of other minds in one stroke by contending that “we use mental terms to indicate that people are disposed to behave in predictable ways. So, for example, when we say that John is angry, we do not mean that he is experiencing some private feeling that we cannot see; rather we simply mean that John is disposed to shout, flush, hit people, break things” (Ryle in C&S: 261). This public character of thoughts and emotions is evidenced in language. Unlike Humpty Dumpty, who said to Alice in a rather scornful tone, “When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean,” I can’t make words mean what I say they do (Lewis Carroll, 1960, The Annotated Alice, Notes by Martin Gardner, 269). Words mean by some sort of public agreement; not by my private endowment. And the evidence of that is, I can get them wrong. Indeed, the language occupying my mind, my thinking, is not private to me. “Private languages” must be a contradiction in terms. I simply borrow words from the public domain to bear my thoughts outward, and perhaps to capture them inwardly as well. But words only count once they get out. That they go dark as they pass through me cannot be of interest with respect to how they get meaning. They get meaning from what they do in the world; I know what the meaning is by inspecting other people’s communicative behavior, not by introspecting my own inner thoughts. Interiority is suspect. Under its strictest interpretation, behaviorists argue that not only do I understand other people’s thoughts only by what they say and perceive other people’s emotions only by what they do, but I grasp my own in that way, too. Errol Bedford, taking up Ryle’s notion a decade later, writes, "I only want to suggest that the traditional answer to the question, 'How do we identify our own emotions?' namely, 'By introspection,' cannot be correct. It seems to me that there is every reason to believe that we learn about our own emotions essentially in the same way as other people learn about them," namely, by examining the external circumstances. (Calhoun and Solomon 1984: 267-268). “I am inclined to think that if an emotion were a feeling no sense could be made of them at all”(Calhoun and Solomon 1984: 274). On this view, we are nothing but Young – 3 behaviors, Goffmanesque performances that bring off a subject-effect, Foucauldian subjectpositions into which we are “interpellated.” But behaviorism participates in the black box model, too, except that it empties the box and attends only to the signals it emits. Neither the observation of external behavior, whose connection to inner states is speculative, nor the introspection of inner states, whose connection to other minds is speculative, is sufficient to account for how we know what other people mean. The British philosopher Barry Smith argues that meaning must be secured from both the inside and the outside, and that the internal aspects of meaning do not stand against the external aspects (Lecture, UC Berkeley, 2003). If words get meaning from some activity that goes on in the mind, then understanding somebody is a guess at what is going on in a private space. If, by contrast, meaning lies on the surface of language, as Smith puts it, then meaning something has to do with what other people understand, regardless of whatever I intend. Securing meaning seems to require either a first-person epistemology, the inner and conscious dimension of language, or a third-person epistemology, the outer and public dimension of language, and each excludes the other. Smith proposes instead a second-person epistemology of meaning by which I try to bring somebody else’s experience into configuration with mine by speaking. This attempt is rooted neither in the private character of thinking nor the public character of speaking but in the experience of seeing somebody point, that is, of putting myself in the place of the other to see what she sees, of participating in her interiority. The possibility of putting my self in the place of the other stems, I take it, from the primordial experience of being a body inside a body. This initial condition is not so much the experience of sharing somebody else's interiority as of being somebody else’s interiority. Object-relations psychologists who take this position see childhood as the process of learning to estrange ourselves from this intimate other, to exteriorize ourselves, we might say. If it is, fortunately, we fail because it is only by continuing to participate in other’s interiorities that we have intimacy. But in the course of trying to make ourselves solipsists, we come to experience our interiority as if it were private to us. The notion that interiority is hidden inside arises in part from visual perception. Visually, I experience my own body, as well as the bodies of others, as an object with an inside to which neither I nor my perceivers has access, by seeing objects disappear into or emerge from the body as an occult space. The visual model lodges me outside my own body on the other side of the split between interiority and exteriority, and produces my own interiority, along with the other’s, as private space. If I were to proceed from tactile perception, by contrast, I would experience my own body, and in some measure the bodies of others, as a lively substance whose inside and outside are perceptible to me, and sometimes to my perceivers, by feeling it. The tactile model lodges me inside a body whose interiority is seamlessly connected to its exteriority by the fact of sensation. Mimesis Among animals, all communication is anticipatory of action. It’s a sort of pre-action or proto-act; animal ethologists describe it as a part-action (Bateson 1972: 141), or sometimes as an intention display or a ritualized gesture. The communication mentions the whole action by enacting part of it. That is, it consists of part of the action it communicates; the part-action is metonymic for the whole. Gregory Bateson describes this sort of communication as iconic or analogic, in contrast to arbitrary or what he calls “digital” communication, of which language is the central instance (1972: 133, 178). Of course language is not fully arbitrary; onomatopoeic words mean what they say and some linguists argue that language may have been deeply analogic at its inception (SheetsJohnstone). In analogic communication, the animal communicates what it has in mind by imitating or partially replicating it. For example, have you ever noticed that when you cat wants its dinner, it rubs against your legs? That’s how a kitten stimulates its mother to release milk, by rubbing against her. So the cat is denoting the act of suckling by representing it iconically. It is imitating Young – 4 the act it wants committed. But in this case the communication does not mean what it denotes. The cat is not a kitten and you are not suckling it. Because it can’t mean what it says, or more precisely, it can’t be what it does, Bateson argues that this is not a “denotative message” but a message about such a message, or what he calls a “metacommunication,” a communication about communication, or frame. Metacommunications are of two sorts: messages about the structure of the message – metalinguistic messages about the speech stream are of this sort – and messages about the relationship between the communicators. In this instance, the cat’s analogy is, “I am to you as a kitten is to a cat;” but what it means metacommunicatively is, “Feed me. Bateson describes communication and frame in terms of Korsybski’s map/territory problem. The map has an analogic relationship with the territory but it is not the territory it maps; it is an instruction for how to perceive or regard something about the territory, what Wittgenstein calls a “description under which.” To treat analogic communication as what it says, or rather as what it does, according to Korzybski, is to confuse the map with the territory. The problem in analogic communication is negation. In order to communicate not something, the animal has to indicate what it has in mind and then deny it; it has to do and not do it. For instance, if an animal wants to indicate that it doesn’t want to fight, it has to mention fighting and then deny it. The animal has to contradict itself. The trouble is that analogic communication cannot distinguish between mentioning something and committing it. In analogic communication, you can’t say no. It’s a paradox. Specifically, it’s the sort of paradox Bateson in his analysis of schizophrenia calls a double-bind. Paradoxes cannot be solved; they are inherently selfcontradictory. They have to be something more like transcended. Paradoxes force a move outside their logic. As Bateson puts it, “the absence of simple negatives is of especial interest because it often forces organisms into saying the opposite of what they mean in order to get across the proposition that they mean the opposite of what they say” 1972: 140). The paradox generates the metacommunicative message. This sort of communication is an aspect of primary process, which Bateson notes is characterized by Fenichel, for instance, as “lacking negatives, lacking tense, lacking in any identification of linguistic mood (i.e., no identification of indicative, subjective, optative, etc,) and metaphoric” (1972: 139). It is the sort of thinking that goes on in dreamwork or in the Freudian unconscious. The dreamer can only dream the event, whether it is an event the dreamer desires or denies. The project of the dreamwork, then, is to cross the event out, to figure out how to express negation. Freud’s insight in The Interpretation of Dreams was how the dream does this. Bertrand Russell illuminates this sort of paradox in his Theory of Logical Types. He distinguishes between members of a class of objects, and the label or frame of the class. The label or frame, the description under which things are members of the class, is at a next higher level of abstraction from the class it labels or frames. It is, in Bateson’s terms, a metacommunication. Russell’s rule is that a class cannot be a member of itself. If you try to make it one, to count the metacommunication as the communication, the map as the territory, the iconic of fighting as the fight it for which it is iconic, you generate a paradox, “This is and is not a fight.” Russell’s Theory of Logical Types is the source of Bateson’s theory of metacommunication. In the case of the animal, mistaking the iconic for fighting for fighting gets it into a fight. And of course this happens. When dogs bare their teeth or nip at each other when they meet, one or the other of them can easily mistake the nip for the bite that it denotes and start fighting. If it does, the animal makes a category mistake. It mistakes the label for what it labels. The actions in which the other animal is now engaged do not mean what they would mean if the animal seriously engaged in them. As Bateson writes, “The playful nip denotes the bite, but it does not denote what would be denoted by the bite” (1972: 180). Young – 5 The animal solves the problem of negation by pulling its punches. It displays its teeth or feints its nip but it doesn’t bite. In Bateson’s famous instance of the monkeys in the Fleischaker Zoo in San Francisco, the metacommunication conveyed by pulling their punches was the message, “This is play.” When the gesturer I examine in this study pulls his punch during a therapeutic interaction, the metacommunication is clearly not, "This is play.” The metacommunication, I shall argue, is “I am angry.” Emotions, Bateson points out, are signs of the relationship between self and others (1972: 140), for both the self and the other. They are metacommunications about the relationship between the communicators. So animals engage in behaviors; they engage in communications about these behaviors in the form of iconic representations of these behaviors; and they engage in metacommunications about these communications about behaviors (1972: 189). Behaviors are themselves acts of communication. For instance, when a female animal is prepared to mate, she issues an odor to which the male animal responds with sexual excitement. Both the secretion of the odor by the female and the arousal of the response in the male are involuntary. Nobody has any choice about it. The sexual secretion, like the sexual arousal, is a mood-sign, “i.e., an outwardly perceptible event which is a part of the physiological process which we have called a mood” (Bateson 1972: 178). At a certain stage in animal evolution, “the organism ceases to respond quite ‘automatically’ to the mood-signs of another and becomes able to recognize the sign as a signal: that is, to recognize that the other individual’s and its own signals are only signals, which can be trusted, distrusted, falsified, denied, amplified, corrected and so forth” (1972: 178). What was once the index or symptom of a relationship has become the sign of a relationship that might not exist. With the recognition that signs can be signals comes the possibility of language, that is, of alluding to a state of affairs that is not then the case (1972: 179). Once the mood-sign becomes a signal, as when the fist is clenched as a gesture rather than as part of the act of punching, it is possible for it to become detached from the emotion it previously signified and now merely signals. Perfumes signal a state of sexual readiness their bearers may not be in. But in the instance of an iconic gesture in which what the hand represents iconically happens to be itself, this detachment is incomplete. By virtue of the hand’s mimesis, the gesture continues not only to allude to but also to perform part of what it denies. When the whole action is an attack, the part action not only retains a metonymic trace of the action but also constitutes an interruption or deferral of the action. The gesture includes its own negation. The mimetic problem with such a gesture is that it threatens to turn into what it imitates. In my talk I will present a punching gesture, affiliated with the word “fight” in a therapeutic conversation, which illuminates the relationship between the interiority of meaning and the exteriority of meaning.