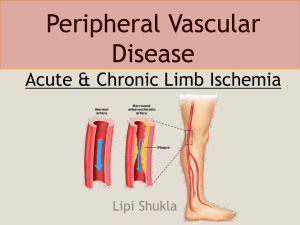

Peripheral Vascular Disease

advertisement

PERIPHERAL VASCULAR DISEASE Paul B. Tabereaux, M.D., M.P.H. WEEK 13 Learning Objectives: 1. To understand the risk factors, clinical presentation, and evaluation of peripheral vascular disease 2. Recognize different modalities of testing for peripheral vascular disease 3. Evaluate the options of medical therapy for this disorder CASE ONE: Ms. A.K. Leggs is a 66-year-old female that presents to your office with complaints of left lower extremity pain. She states that while walking on the golf course she gets pain in her lower calf, primarily on her left side. She states that when she stops and rests on a bench at the next tee, the pain slowly resolves. She does not have the pain when she uses a golf cart. Her past history is significant for HTN, hyperlipidemia (Recent: LDL 160, Triglycerides of 210). She takes HCTZ, and was recently started on atorvastatin 10mg after her recent lab work. Examination of her legs shows that her left leg is slightly cooler to the touch than her right. There is paucity of hair on her lower leg and on exam you note a diminished posterior tibial pulsation. Questions: 1. What risk factors does this patient have for peripheral vascular disease? Atherosclerosis is the leading cause of occlusive arterial disease of the extremities in patients over 40 years old; the highest incidence occurs in the sixth and seventh decades of life. As in patients with atherosclerosis of the coronary and cerebral vasculature, there is an increased prevalence of peripheral atherosclerotic disease in individuals with diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, or hyperhomocysteinemia and in cigarette smokers. 2. What clues for PVD should be ascertained in the history and physical? Fewer than 50% of patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) are symptomatic, though many have a slow or impaired gait. The most common symptom is intermittent claudication, which is defined as a pain, ache, cramp, numbness, or a sense of fatigue in the muscles; it occurs during exercise and is relieved by rest. The site of claudication is distal to the location of the occlusive lesion. For example, buttock, hip, and thigh discomfort occur in patients with aortoiliac disease (Leriche syndrome), whereas calf claudication develops in patients with femoral-popliteal disease. Symptoms are far more common in the lower than in the upper extremities because of the higher incidence of obstructive lesions in the former region. In patients with severe arterial occlusive disease, critical limb ischemia may develop. Patients will complain of rest pain or a feeling of cold or numbness in the foot and toes. Frequently, these symptoms occur at night when the legs are horizontal and improve when the legs are in a dependent position. With severe ischemia, rest pain may be persistent. Important physical findings of PAD include decreased or absent pulses distal to the obstruction, the presence of bruits over the narrowed artery, and muscle atrophy. With more severe disease, hair loss, thickened nails, smooth and shiny skin, reduced skin temperature, and pallor or cyanosis are frequent physical signs. In addition, ulcers or gangrene may occur. Elevation of the legs and repeated flexing of the calf muscles produce pallor of the soles of the feet, whereas rubor, secondary to reactive hyperemia, may develop when the legs are dependent. The time required for rubor to develop, or for the veins in the foot to fill when the patient's legs are transferred from an elevated to a dependent position, is related to the severity of the ischemia and the presence of collateral vessels. Patients with severe ischemia may develop peripheral edema because they keep their legs in a dependent position much of the time. Ischemic neuritis can result in numbness and hyporeflexia. 3. How would you begin your workup for PVD? ABI’s – please see Figure 1 of the NEJM article. A relatively simple and inexpensive method to confirm the clinical suspicion of arterial occlusive disease is to measure the resting and post-exercise systolic blood pressures in the ankle and arm. This measurement is referred to as the ankle-brachial (or ankle-arm) index or ratio and provides a measure of the severity of peripheral vascular disease. Calculation of the ankle-brachial index (ABI) is performed by measuring the systolic blood pressure (by Doppler probe) in the brachial, posterior tibial, and dorsalis pedis arteries. The highest of the four measurements in the ankles and feet is divided by the higher of the two brachial measurements: Normal ABI is 1.0 to as high as 1.3, since the pressure is higher in the ankle than in the arm. An ABI below 0.9 has 95 percent sensitivity (and 100 percent specificity) for detecting angiogram-positive peripheral vascular disease and is associated with 50 percent stenosis in one or more major vessels. An ABI of 0.40 to 0.90 suggests a degree of arterial obstruction often associated with claudication. An ABI below 0.4 represents advanced ischemia. If ABIs are normal at rest, but symptoms strongly suggest claudication, ABIs and segmental pressures should be obtained before and after exercise on a treadmill or using active pedal plantar flexion, which involves repeatedly standing up on the toes. A potential source of error with the ABI is that calcified vessels may not compress normally, possibly resulting in falsely elevated Doppler signals. An ABI above 1.3 is suspicious for a calcified vessel, especially among patients with diabetes mellitus. In some patients with arterial calcification, an accurate pressure may be obtained by measuring the toe pressure. In this setting, one must recognize that a pressure gradient of 20 to 30 mmHg normally exists between the ankle and the toe. 4. What further tests may be performed if an abnormal result is found? The next diagnostic test after ABI is segmental pressures and pulse volume recording amplitudes, performed in the vascular laboratory. Some laboratories also perform duplex Doppler ultrasound, evaluating the spectral waveform. After these tests, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is recommended to evaluate for the extent and level of disease. MRA is usually performed if revascularization is being considered. 5. Can PVD be asymptomatic? In one report, 239 men and women ages 55 and older with no history of PVD were recruited from a general internal medicine practice and evaluated in a noninvasive vascular laboratory. The ankle-brachial index (ABI) was abnormal (<0.9) in 14%. While most patients did not report exertional leg symptoms, they were not able to walk as far in six minutes as a group of patients without PVD (1,362 versus 1,539 feet). Detection of asymptomatic PVD has value because it identifies patients at increased risk of atherosclerosis at other sites. As an example, as many as 50% of patients with PVD have at least a 50% stenosis in one renal artery. Thus, patients with asymptomatic PVD, most often detected by ABI, should be aggressively treated with risk factor reduction. 6. What medical therapy options would you offer to this patient? The medical management of moderate to severe intermittent claudication secondary to peripheral vascular disease involves three modalities: Risk factor modification All patients with claudication should also be encouraged to modify risk factors for vascular disease. Lipid- lowering is clearly beneficial in patients with peripheral vascular disease. The benefits of smoking cessation, diabetes control, and lowering blood pressure in terms of improving claudication symptoms are not clear, but can be recommended on other grounds. Beta-1 selective blockers do not appear to adversely effect claudication symptoms. ACE inhibitors may protect against cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral vascular disease. Exercise training or rehabilitation A supervised exercise program should be considered in all patients who are motivated and have the necessary resources. A meta-analysis of 21 non-randomized and randomized studies found that exercise training increased the distance to onset of claudication by 179%. The greatest improvements in walking ability occurred when each exercise session lasted more than 30 minutes with at least three exercise sessions per week, when the patient walked until near maximal pain was reached at each session, and when the program continued for at least six months. A later meta-analysis that considered only randomized, controlled trials, found that exercise produced significant improvements in walking time compared with both angioplasty and antiplatelet therapy. Pharmacologic therapy Antiplatelet agents are warranted in all patients with claudication. The Sixth American College of Chest Physicians Consensus Conference recommended that aspirin alone (81 to 325 mg/day) or in combination with dipyridamole should be given indefinitely because it can modify the natural history of intermittent claudication and because these patients are at high risk for future cardiovascular events. The guidelines suggest that clopidogrel may be superior to aspirin and should be considered an alternative treatment. Cilostazol is probably the most effective drug therapy; the optimal clinical therapeutic benefit resulting in improved pain free walking distance is likely to occur with the combination of exercise and cilostazol. Cilostazol appears to be more effective than pentoxifylline. This was illustrated in a trial of 698 patients randomly assigned to pentoxifylline (400 mg TID), cilostazol (100 mg BID), or placebo for 24 weeks. The increase in mean maximal walking distance over baseline with pentoxifylline and placebo was the same (30 and 34 percent, respectively), but the increase with cilostazol was significantly greater (54 percent). The Sixth ACCP Consensus Conference recommended a trial of cilostazol in patients experiencing disabling claudication, particularly when lifestyle modification alone is ineffective and revascularization cannot be offered or is declined by the patient. Cilostazol is not recommended for routine use in all patients because of its cost and modest clinical benefit. Cilostazol may be taken safely with aspirin and/or clopidogrel without an additional increase in bleeding time. BONUS: 7. What are the indications for using a revascularization technique in individuals with PVD? Surgery should be limited to low risk patients with disabling symptoms who can be expected to tolerate the procedure and live long enough to enjoy the improved quality of life; patients who benefit most from elective surgical revascularization are generally under 70 years of age, nondiabetic, and have little evidence of disease distal to the primary lesion. Revascularization using percutaneous techniques is indicated when the patient has lifestyle- limiting claudication that does not respond to conventional medical therapy; it may also be considered in patients who have severe disease when there is a focal stenosis or occlusion, in some cases to augment a surgical procedure, and in patients who have limb threatening ischemia but are not surgical candidates. References: 1. Hiatt, WR. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. NEJM 2001; 344:1608-1621. Additional References: 1. Kasper, DL. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 16th Edition 2. McDermott, M.M. et al. Prevalence and significance of unrecognized lower extremity peripheral arterial disease in general medicine practice. JGIM 2001; 16:384-90 3. Mohler, ER. Medical management of claudication. UpToDate 2004 4. Mohler, E.R. et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of peripheral vascular disease. UpToDate 2004