Pneumonia

advertisement

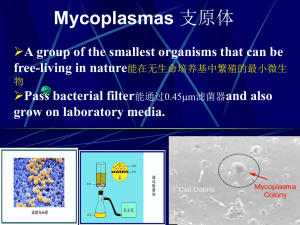

Pneumonia Pneumonia is an acute infection of the parenchyma of the lung, caused by bacteria, fungi, virus, parasite etc. Pneumonia may also be caused by other factors including X-ray, chemical, allergen. It is the common disease in our country, 2500000 cases occur annually, 125000 cases die of this disease. In aged or immunocompromised patient (using immunosuppressive agents, transplantation, diabetes mellitus, uremia, alcoholism) with pneumonia. The mortality is much higer. Pneumonia can be classified by pathogen or anatomy. According to the pathogen classification, it is most useful to treat the patients by choosing convenient antimicrobial agents. In diagnosis, two classification can be combined altogether. Ⅰ.Classification by pathogen Microscopic examination in site of infection (alveolar, bronchi or lung), sputum culture, biopsy of lung tissues are useful to identifier the pathogen of the infection. 1. Bacterial pneumonia (1) Aerobic Gram-positive bacteria, such as streptococcus pneumoniae, staphylococcus aureus, Group A hemolytic streptococci. (2) Aerobic Gram-negative bacteria, such as klebsiella pneumoniae, Hemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli. (3) Anaerobic bacteria. 2. Atypical pneumonia includes legionnaies pneumonia, Mycoplasmal pneumonia and Chlamydia pneumonia and ects. 3. Fungal pneumoniae Fungal pneumonia is commonly caused by candida. 4. Viral pneumonia Viral pneumonia may be caused by adenoviruses, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex. 5. Pneumonia caused by other pathogen. Rickettsias (a fever rickettsia), chlamydia psittaci, parasites, protozoa. Ⅱ.Classification by anatomy 1. Lobar: Involvement of an entire lobe. 2. Lobular: Involvement of parts of the lobe only, segmental or of alveoli contiguous to bronchi (bronchopneumonia). 3. Interstitial Ⅲ. Classification by acquired environment 1. Community acquired pneumonia (CAP) CAP refers to pneumonia acquired outside of hospitals or extended-care facilities . Streptococcus pneumoniae remains the most commonly identified pathogen. Other pathogens include Haemophilus influenzae, mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophilia pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis and ects. 2. Hospital acquired pneumonia (HAP) HAP refers to pneumonia acquired in the hospital setting. Enteric Gram-negative organisms, S. aureus, Pneudomonas aeruginosa, ects. Pneumococcal pneumonia Pneumococcal pneumonia is produced by streptococcus pneumoniae. It is the most commonly occurring bacterial pneumonia. Patients have the symptoms of shaking chill, sharp pain, cough, and blood-flecked sputum. Etiology, pathogenesis and pathology Streptococcus pneumonia are encapsulated, gram-positive cocci that occur in chains or pairs. The capsule which is a complex polysaccharide has specific antigenicity. At least 86 different immunogenic types exist by serologic test. Type 3 is the most virulent, usually causing severe pneumonia in adults, but type 6,14,19 and 23 are virulents is children. The pneumonia is directly proportional to the innoculum size and virulence of the organisms, and inversely related to the adequacy of pulmonary host defenses. Pathology Once a sufficient inoculum of sufficiently virulent pneumococci has reached the alveoli, pneumonia develops, first there is alveolar capillary congestion, stage of congestion, than fluid pours out from capillaries to fill the alveoli, spreading to adjacent alveoli. This infected tide carries pneumococci into contiguous areas until in flow is stopped by an anatomic barrier, usually the visceral pleura investing a segment or a lobe of the lung. This stage of pneumonia is called “red hepatization” because of the liver-like, reddish appearance of the consolidated lung. A few hours after pulmonary capillaries dilate and edema fluid pours into the alveoli, polymorphnuclear leukocyte enter the alveolar spaces, rapidly fill the alveoli, and consolidate the lung (called grey hepatization). Finally, macrophages migrate into the consolidated alveoli and ingest the debris left behind as the acute infection resolves (called resolution). All of the four main stages of the inflammatory reaction described above may be present at the same time. In most cases, recovery is complete with restoration of normal pulmonary anatomy. In 5% to 10% of patients, infection may extend into the pleural space and result in an empyema or in 15% to 20% of patients, bacteria may enter the blood stream (bacteremia) via the lymphatics and thoracic dust. Invasion of the blood stream by pneumococci may lead to serious metastatic disease at a number of extra pulmonary sites (meningitis, arthritis, pericarditis, endocarditis, peritonitis, otitis media etc). Clincal manifestation Many patients have had an upper respiratory infection for several days before the onset of pneumonia. Onset usually is sudden, half cases with a shaking chill. The temperature rises during the first few hours to 39-40℃. The pulse accelerates. Sharp pain in the involved hemi thorax. The cough is initially dry with pinkish or blood-flecked sputum. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea may be mistaken as acute abdominal inflammation. Signs The acutely ill patient is tachypneic, and may be observed to use accessory muscles for respiration, and even to exhibit nasal flaring. Fever and tachycardia are present, frank shock is unusual, except in the later stages of infection or DIC. Auscultation of the chest reveals bronchovesicular or tubular breath sounds and wet rales over the involved lung. A consolidation occurs, vocal and tactile fremitus is increased. Complications Complications are less seen recently. If sepsis occurs, the patient may become dusky, cyanotic, confused and shock. 1. sepsis 2. lung abscess or empyema 3. pleural effusion, pleuritis 4. ARDS , ARF 5. pneumothorax 6. Extrapulmonary infections Laboratory examination The peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count is often 10-30×109/L, of 80% in the polymorphonuclear leukocytes. However, in alcoholics or immunosuppressed patients. It may be normal or low of more value is the WBC differential, which consists predominantly of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (left shift). Before using antibiotic, the culture of blood of 20% is positive. Microscopic examination and culture of expectorated purulent sputum between 24-48 hours can be used to identify pneumococci. Colony counts of bacteria from bronchoalveolar lavage washings obtained during endoscopy are seldom available early in the course of illness. Use of the PCR may amplify pneumococcal DNA and improve potential for detection. X-ray examination Chest radiographs reveal a lobar distribution and an air space pattern of disease. If blunting of the costophrenic angle is noted, the finding is believed to represent an effusion. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis The clinical picture and radiographic features associated with, it is not difficult to make the diagnosis. 1. pulmonary tuberculosis 2. Other microbial pneumonias: Klebsiella pneumonia, staphylococal pneumonia, pneumonias due to G (-) bacilli, viral and mycoplasmal. 3. Acute lung abscess 4. Bronchogenic carcinoma 5. Pulmomary infarction Treament 1. Antibiotic therapy All patients with suspected pneumococcal pneumonia should be treated as promptly as possible with penicillin G. The dose and route of delivery may have to be on the basis of patients status adverse reaction or complication that occur. For patients who are believed to be allergic to penicillin, one may select a first or second generation cephalosporin or erythromycin, clindamycin, or a fluoroquinolone. Treatment with any effective agent should be given for at least 5 to 7 day or after the patients have been afebrile for 2-3 days. 2. Supportive measure Supportive measure are generally used in the initial management of acute pneumococcal pneumonia: Such measures include bed rest; monitoring vital signs and urine output; administering an occasional analgesic to relieve pleuritic pain; replacing fluids, if the patient is dehydrated; correcting electrolytes; oxygen therapy. When relieving pleuritic pain or providing sedation in situations requiring it, care should be taken to not use excessively high doses of analgesics or sedatives that might depress the respiratory center. If possible, antipyretics should also be avoided because these agents interfere with the evaluation of fever as a measurement of the patient’s progress, and cause a dehydration. 3. Treatment of complications Empyema develops in appoximately 5% of patients with pneumococcal pneumonia, although pleural effusion commonly develop in 10%-20% patients. Chest X-ray with lateral decubitus films are often useful in the early recognition of pleural effusion, pleural fluid that is removed should be subjected to routing examination. If pneumococcal bactermia occurs, extra pulmonary complications such as arthritis, endocarditis must be excluded, because their therapy requires higher dosages. 4. Treament of infections shock (1) Treatment in intensive care units (2) cardiac rhythm, blood pressure, cardiac performance, oxygen delivery, and metabolic derangements can be monitored (3) Adequate oxygenation and ventilatory support (sometimes mechanical ventilation) (4) Effective antibiotic therapy (5) Maintain blood pressure, including maintain circulation blood volume, use of dopamine 5. Prognosis Prognosis is much better. Any of the following factors makes the prognosis less favorable and convalescence more prolonged elderly; involvement of 2 or more lobes; underlying chronic diseases (heart lung kedney) normal temperature and WBC count <5000; immunodeficiency with severe complication. Prevention The most important preventive tool available is using a poly valent pneumococcal vaccine in those with chronic lung diseases, chronic liver diseases, splenectomy, diabetes mellitus and aged. Staphylococcus pneumonia Staphylococcal pneumonia is usually caused by staphylococcus aureus. It is often a complication of influenza, but may be primary, particularly in infants and the aged. It occurs in immunocompromissed patients such as diabetes mellitus, nematologic disease (leukemia, lymphoma, leukopenia), AIDS, liver disease, malnutrition, alcoholism. Staphylococcal bacteremia complicating infections at other sites (furuncles, carbuncles) may cause hematogenous pulmonary involvement (due to blood spread). Some or all of the symptoms of pneumococcal pneumonia (high fever, shaking chill, pleural pain, productive cough) may be present, sputum may be copious and salmon-colored. Prostration is often marked. According the symptoms, signs of pneumonia, leukocytosis and a positive sputum or blood culture, the diagnosis can be made. Gram stain of the sputum provides earliest diagnostic clue. Chest X-ray early in the disease shows many small round areas of densities that enlarge and coalesce to from abscess, and leave evidence of multiple cavities. Until the sensitivity results are know, a penicillinase –resistant penicillin or a cephalosporin should be given. Therapy is continued for 2 weeks after the patient has become afebrile and the lungs have shown signs of clearing. Vancomycin is the drug of choice for patients allergic to penicillin and cephalosporin and for those not responding to other antistaphylococcal drugs and for MRSA. Pneumonia caused by klebsiella Klebsiella pneumonia (also named Friedlander pneumonia) is an acute lung infection, caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae 1, it occurs much more in aged, malnutrition, chronic alcoholism, and in whom with bronchial pulmonary disease. The onset usually is sudden, with high fever, cough, pleuritic pain, abundant sputum, cyanosis, tachycardia my be present, half cases with a shaking chill. Shock appears in early stage. Clinical manifestations are similar to sever pneumococcal pneumonia. The sputum is viscid and “ropy”, and may be “brick red” in color. Chest X-ray shows a downward curve of the horizontal interlobar fissure, if the right upper lobe is involved. Areas of increased radiance within dense consolidation suggest cavitation. It constitutes 2% of bacterial pneumonia, but mortality may be as high as 30%. When an elderly patient suffered from acute pneumonia with sever toxic symptom, viscid and “brick red”, sputum must consider this disease. The diagnosis is determined by bacterial examination of sputum. Early using antimicrobial therapy is important for patients with survivable illnesses, the third or fourth generation cephalosporin and aminoglycoside (Kanamycin, Amikacin, Gentamycin) are often used. Mycoplasmal pneumonia Mycoplasmal pneumonia is caused by Mycoplasmal pneumoniae. Mycoplasmal pneumoniae is one of the smallest organisms 125-150 μm capable of replication in cell-free media. Infection is spread form person to person by respiratory secretions expelled during bouts of coughing, causing epidemic or sporadic occurance. It commonly occurs in children, adolescent, mainly in fall and winter. It constitutes more than 1/3 of non bacterial pneumonias, or 10% of pneumonias from all cause. Mycoplasmal pneumonia is caused by Mycoplasmal pneumoniae. Mycoplasmal pneumoniae is one of the smallest organisms 125-150 μm capable of replication in cell-free media. Infection is spread form person to person by respiratory secretions expelled during bouts of coughing, causing epidemic or sporadic occurance. It commonly occurs in children, adolescent, mainly in fall and winter. It constitutes more than 1/3 of non bacterial pneumonias, or 10% of pneumonias from all cause. Cellular infiltrate around bronchioles, and in alveolar interstitium, consists mostly of mononuclear elements. Clinical findings The illness begins insidiously with constitutional symptomatology: malaise, sore throat, cough, fever, myalgia, half of cases have no symptom. Chest X-ray findings are manifold. Most patients have unilateral lower lobe segmental abnormalities. The earliest signs are an interstitial accentuation of marking with subsequent patch air space consolidation and thickened bronchial shadows. The pneumonia may persist for 3-4 weeks a slight leukocytosis is seen, with a normal differential count. The diagnosis is generally proved by a single antibody titer of 1:32 or greater, a titer of cold agglutinins of 1:32 or greater a single IgM determination. The most promising in terms of speed, sensitivity and specificity is PCR although cost and lack of general availability limit its routine use. Therapy A definite clinical response is seen to erythromycin and tetracyclines. Nowadays newer generation of fluoroquinolones are effective. 参考教材 1. 内科学(供七年制) ,人民卫生出版社 2. Cecil Textbook of Medicine,21st edition 3. 邓伟吾主编,实用临床呼吸病学,中国协和医科大学出版社