The Devolution of Education in Pakistan

advertisement

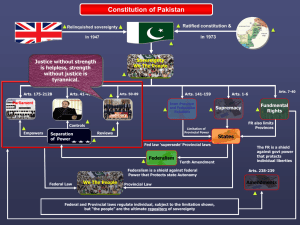

THE DEVOLUTION OF EDUCATION IN PAKISTAN by Donald Winkler Randy Hatfield May 2002 A report written by Donald Winkler and Randy Hatfield based in part on the results of visits to Punjab and Sindh provinces and meetings with officials at the Federal, Provincial, and District levels. Thanks are given to those officials as well as staff at the Aga Khan University Institute of Education, the Sindh Education Foundation, the National Rural Support Program, SAHE, and Idara-e-Taleem-o-Agahi Public Trust. INTRODUCTION. Pakistan is in the process of devolving significant service delivery responsibilities from its four provincial governments to 6,455 new, and newly-elected, local selfgovernments. The fact that the country is in process of implementing devolution means that there are significant differences between what is written in law or regulations [de jure] and what actually occurs on the ground [de facto], as well as large variations between districts and provinces in terms of where they are in the implementation process. The major de jure change facing the education sector is the transfer of the responsibilities for recruiting, paying, and managing teachers and headmasters from the provincial ministry of education to the district governments where a newly created position—the Executive District Officer [EDO] for education—reports directly to a newly created Chief District Officer [CDO], who in turn reports to an elected Nazim [mayor] and elected District Council. In addition, each province has crafted its own law or regulation creating popularly elected School Management Councils [SMCs] with the authority to receive government funding and to decide on the allocation of funds. The transfer of responsibilities has been accompanied by a transfer of revenues from provincial to district governments. [This discussion will in general ignore the changes to sub-district level governments as they have no legal responsibility vis a vis education.] As an interim measure, the funding the provincial government had budgeted for the decentralized services in fiscal year 2002 has been transferred to the districts, but beginning with the 2003 fiscal year each province will develop its own formula-driven block grant to the districts. Considering the fact that the National Reconstruction Bureau [NRB] only initiated the design of Pakistan’s devolution in March 2000, rapid progress has been made in electing thousands of public officials at the district, tehsil, and union levels, and recruiting Education EDOs in 96 districts. As might be expected, not everything has gone smoothly. Many district education staff do not know their own terms of reference; some are confused as to the roles of the new district cadres and who is their employer; the authority of the SMCs to help manage teachers [e.g., to monitor their attendance] is in some legal question; and the district-level capacity to manage large budgets and civil service bureaucracies, mostly teachers, is in some doubt. Of particular concern is the financial management capacity of district governments. Numerous other questions can be asked about the devolution of education in Pakistan. Will the new structure improve parent/voter “voice”, or will the political process be captured by either the local elite or the district bureaucracy? Will it improve the accountability of the education bureaucracy to beneficiaries, on one hand, and to the newly elected district political officials, on the other? Does the new system change the incentives facing key actors and thus alter their behavior, or does the fact that few faces have changed in the bureaucracy mean the lack of behavioral change as well? Which level of government is now responsible for some important responsibilities, e.g., compensatory education programs to improve equity? What is the role of public-private partnerships [e.g., the adopt-a-school programs], and which level of government is responsible for setting the rules of the game and supervising those partnerships? How will newly elected bodies—e.g., the SMCs—and newly recruited officials—e.g., the EDOs—develop new management and political skills? Will Pakistan learn from its successes and mistakes in devolution, or will the same mistakes be repeated? It is premature to try to answer these questions, but it’s important that a monitoring and learning process be put in place to permit answers in, say, two years’ time. In the pages that follow we first examine the educational context within which devolution is occurring and document the very large challenge that lies ahead to raise coverage [especially in rural areas and for girls], to increase educational attainment, and to improve equity. Next, we examine how devolution has changed the roles and responsibilities of the various levels of government and of the key actors in the educational system. Of necessity, this examination looks only at changes in de jure roles and responsibilities; part of the monitoring assignment must be to also document the difference between the de jure and the de facto. THE EDUCATIONAL CONTEXT OF DEVOLUTION. Devolution in Pakistan is occurring in the context of low educational attainment, poor coverage, and highly unequal access—across income groups, between urban and rural populations, and between males and females. The statistics presented below paint a bleak portrait of education development in Pakistan. According to the PIHS of 1998-9, only 42 percent of adults above age 15 are literate, with huge urban-rural and male-female differences. While 73 percent of urban males are literate, the corresponding figure for rural females is less than 17 percent. These figures, of course, represent the past as well as the present. One would hope that illiteracy would decline sharply in the future in response to improved access to primary schooling for younger generations. Unfortunately, the data do not support such optimism. Again, according to the 1998 PIHS, only 50 percent of all children aged 6-10 were in fact enrolled in primary school. The net enrollment rate [NER] for urban boys was 68.5 percent, below the literacy level of the corresponding adult population, while the NER for rural girls was only 36 percent. In the Tribal Areas, less than 9 percent of girls aged 6-10 were enrolled in school. Finally, almost half of all children aged 17 from poor households have never even attended school. In addition to low literacy rates and low coverage of primary education, there is high inequality in terms of access to schooling. A child aged 6-10 living in an urban area is 47 percent more likely to attend primary school than is a similarly-aged child in a rural area in Pakistan, and a boy aged 6-10 is 31 percent more likely to attend primary school than is a girl. At the secondary level, these inequalities increase. A child aged 11- 15 in an urban area is almost twice as likely as a child in a rural are to be attending secondary school, and a boy aged 11-15 is 52 percent more likely to attend secondary school than is a girl. The secondary school NER for urban boys is three times that for rural girls. Disaggregating enrollment by household income/expenditure level, one finds that the primary school gross enrollment rate [GER] for children in the richest decile is 2.6 times that for children in the poorest decile, and at the secondary school level, this ratio increases to 5.4. Little information is available on the quality of schooling, but parents often make an effort to enroll their children in private schools in the belief that they offer a higher quality of schooling. Even a surprising number of very poor parents manage to send their children to private schools. However, the difference in access to private schools across income groups is large. While almost 60 percent of parents in the richest decile send their children to private primary schools, less than 10 percent of parents in the poorest decile manage to do so. Unfortunately, Pakistan is not making rapid progress in improving access to schooling. According to PIHS data, the overall GER has declined since 1995, after increasing between 1991 and 1995. The decline has been especially sharp for rural males. In addition, the gap in GER between boys and girls has remained constant since 1995, after decreasing between 1991 and 1995. One of the explanations for Pakistan’s poor educational performance appears to be the lack of accountability in public education. A survey of public schools reported by Gazdar [2000] found that less than half the public schools to be fully functional; only three-quarters of schools on the books were in fact open, and of the open schools 24 percent had less than half the teachers present. THE DEVOLUTION OF EDUCATION. The devolution of public education in Pakistan is not a response by the education authorities to widespread dissatisfaction with the performance of the existing system, although the Federal Government has advocated increased decentralization at several times in the past. Rather, the current education devolution is a direct result of the President’s August 2001 initiative to devolve a number of responsibilities from provincial to newly elected district and sub-district level governments. This devolution plan, designed by the National Reconstruction Board [NRB], entails transferring responsibilities—including primary-secondary education--and revenues from provincial to district level governments. More details on the nature of devolution of education in Pakistan follow. Fiscal decentralization. Prior to devolution, provincial governments received most their revenues [82 percent in 2000-01] from a pool of shared revenues collected nationally. This revenue sharing does not change under devolution. What does change is that provincial governments are required to devise mechanisms to in turn transfer revenues to district level governments, and district level governments are empowered to share their revenues with sub-district level governments. The revenue transfers from provinces to districts will be in the form of formula-driven block grants, which will not be earmarked for specific uses. Civil service decentralization. Prior to devolution, most civil servants belonged either to the Federal or provincial cadres [several municipalities also had their own employees]. High level provincial education officials belonged to the Federal cadre, as did the appointed Chief District Officer. District education officers, teachers and other education officials belonged to the provincial cadre. Devolution has created a third, district cadre of civil servants, and teachers and most district education officials are to be transferred from the provincial to the district cadres. This means that most education staff will now directly report to district government administrators. Ironically, this does not mean that district governments will set the pay of district civil servants. Pay levels will continue to be set nationally. Expenditure decentralization. Prior to devolution, education budgets and expenditures were determined by provincial officials at the provincial level of government. Subsequent to devolution, district officials will determine education budgets and expenditures, excepting for those standard-setting and monitoring functions remaining at the provincial and Federal levels. In addition, both the provincial and Federal governments will make additional transfers to the districts earmarked for specific educational uses [e.g., the different “windows” of the new Federal Education Sector Reform]. New Roles and responsibilities. The de jure new roles and responsibilities of the different levels of government, from the Federal level down to the newly created, elected School Management Committee [SMC] are shown in Table 1. De facto the educational system is still in transition, with many education personnel considering themselves to still be provincial staff, with district education budgets still largely defined at the provincial level, and with some provinces still defining the composition and responsibilities of the school management committees [SMC].1 However, this transition phase should be completed prior to the beginning of the 2003 fiscal year. 1 The Local Government Ordinance of August 14, 2001, does not define the roles, responsibilities and composition of the SMCs; these decisions were left to the provincial governments, each of which is making somewhat different decisions. Table 1: Roles and Responsibilities Under Devolution Level of Federal Government S Teacher Pay S Teacher Recruitment Teacher Transfer Teacher Evaluation Teacher Training Regulation of Private Schools S Finance P Curriculum School Construction School Maintenance P Evaluation Inspection SH Compensatory Education Provincial District Tehsil School Community [SMC] P P P P P S P ? S S P S P P S P SH P=primary responsibility; S=secondary responsibility; SH=shared responsibility Federal Role. Under devolution, the Federal Government is responsible for setting teacher pay levels, defining required teacher credentials, setting the national core curriculum, and assessing student performance through a national examination. Through the allocation of funds, it, also, plays a shared, role in ensuring equity in education. However, its role in the new system in ensuring disadvantaged children have access to schooling is still not defined. Provincial Role. The provincial governments have a much more restricted role under devolution than was true pre-devolution. They retain primary responsibility for pre-service teacher training and share responsibility for in-service training with the district governments. Potentially, they have an important role to play in ensuring equity in access to schooling, and they can play other important roles in influencing curriculum and ensuring quality should they wish to to exercise those roles. District Role. The district governments have acquired significantly greater responsibilities under devolution. Education is a labor intensive service, and which level of government controls personnel functions by and large defines whether education is decentralized or not. Under devolution, the responsibility for paying and managing teachers clearly lies at the level of the district, even though teacher pay levels and teacher educational requirements are set nationally. This is a significant change from the predevolution arrangement where provincial governments managed and paid teachers. Education finance is another key variable in defining decentralization. Here, too, the primary responsibility under devolution lies with the district government. While the source of revenues is Federal revenues transferred on to the provinces and retransferred on to the districts, it is the district which will decide how much to spend on education vs. other public services for which it is responsible. Finally, the district governments have acquired lead responsibilities in deciding where to locate new schools and how to finance their construction and in inspecting schools to ensure they comply with standards and in carrying out the annual evaluation of teachers and headmasters. Sub-district community organizations called Community Development Boards [CDBs] may, also, play an important role in determining the location and timing of new school facilities; their precise role is still undefined. Key Actors. Devolution has altered the roles and responsibilities of key actors in the education system. As shown in Table 2, the province-level actors have reduced responsibilities with respect to the day to day management of the education sector. They could, of course, assume new—and even more important--responsibilities for monitoring, ensuring quality, providing technical assistance, and stimulating change, but to do so would require a difficult change of mindset and, most likely, replacement of many existing staff by new recruits with the newly required skills. Table 2: Key Actors and Their Responsibilities. Name Provincial Minister of Education Core Responsibilities Acts as the spokesperson for education in the Provincial Assembly Recruitment Appointed by Provincial Chief Minister from the District Management Group [DMG] of the Federal Civil Service Notes No change in core responsibilities and recruitment. However, in some provinces has relinquished role of hiring, firing and transferring of teachers and other professional staff Provincial Secretary of Education Advises on policy issues; Acts as Chief Executive Officer of the Department of Education and is responsible to implement and evaluate policies and plans in the province Appointed by the Provincial Minister of Education from the DMG of the Federal Civil Service No change in responsibilities and recruitment. Director, Primary Education &Literacy Has power to appoint and transfer staff at B-16 level and above; coordinates between Government and District Administration; makes arrangements for teacher training; responsible for setting and monitoring policy and standards in primary education. Recruited from Provincial Civil Service-Education In NWFP and Balochistan, the EDO, Education reports to this officer as well as the DCO Division Education Officer Had responsibility for overall coordination and management of the education sector at the division level. Recruited from Provincial Civil Service-Education Position abolished; functions moved to the EDO, Education. Name District Nazim Core Responsibilities Is the district political officer responsible for education, including proposing the education budget to the District [Zila] Council and, appointing the District Coordinating Officer [DCO]. Recruitment Indirectly elected by Chairpersons of Union Councils Notes Three-year tenure District Coordinating Officer [DCO] Coordinates district administration; appoints and reviews performance of District Officers, including Executive District Officer [EDO]. Recruited from the DMG of the Federal Civil Service Replaces the former Deputy Commissioner in a district; Reports to the elected Nazim Executive District Officer [EDO] (Education) Prepares comprehensive district development plan; implements and monitors educational activities; prepares and controls budget; Monitors and supervises public and private educational institutions; Approves procurement of goods and the appointment, transfer, promotion, selection, and leave of teachers and other education staff; has overall responsibility for annual performance evaluations. Recruited from Provincial Civil Service-Education New post under Local Government Ordinance [LGO] District Education Officer [DEO] (Male & Female) Supervision and monitoring of schools; reports to EDO; there are separate DEOs for different branches/levels of schools. Recruited from Provincial Civil Service-Education No change in responsibility and recruitment Assistant DEO Located at the sub-district level; directly reports to the DEO; writes annual performance evaluations of headmasters and teachers. Recruited from Provincial Civil Service-Education Learning Coordinator Gives demonstration lessons to teachers; Advises on classroom management, and Reports teacher absenteeism Selected on the basis of seniority. Tehsil Nazim Formulate & implement strategies for development of municipal infrastructure and improvement of delivery of the municipal services of the tehsil; Indirectly elected by vice chairpersons of the Union Councils Union Nazim Participates in Sectoral Monitoring Committees including education; Approves Annual Development Plan and budgetary proposals of the Union Administration; Facilitates the formation and functioning of the Citizen Community Boards Mobilizes resources to improve schools; voices community concerns to local government Directly elected Function of the SMC is to provide general support for maintenance of school facility, monitoring of teachers & checking absenteeism Directly supervises teachers; coordinates with SMC Elected by members of the Committee who are directly elected. Provides classroom instruction and administers tests Elect members of SMC, Union councilor, member of Provincial Parliament. Recruited by Provincial Public Service Commission Citizen Community Board [CCB] representatives President of School Management Committee [SMC] Headmaster Teacher Parents Selected by Union Councils Promoted within Provincial teacher cadre. Eliminated in some provinces [e.g., NWFP]. PTAs/SMCs are being merged with CCBs in Sindh to legitimize them legally and constitutionally Usually a member of the SMC; formerly was automatically the SMC President. To be recruited from a District Cadre under LGO The district level officials have acquired new roles and greater responsibilities for managing education. However, with the exception of the EDO, Education, there have been almost no changes in the individuals holding key staffing positions. Hence, while they sometimes have additional and changed responsibilities, they may find it difficult to effectively assume their new roles. One should not underestimate the significance of the newly created position of EDO, Education. For the first time, there exists someone at the district level who has responsibility for the entire education sector, as opposed to a particular branch within the sector. Hence, districts should be better able to make the difficult decisions about how to allocate resources across branches and levels of education. Finally, it is important to note that the selection of and the responsibilities of the headmaster remain essentially unchanged. Thus, the individual with the most local knowledge and, thus, arguably the best-informed to make local resource decisions does not have the authority [and, in some cases, the capacity] to do so. DEVOLUTION AND ACCOUNTABILITY. One objective of the devolution of government in Pakistan is to improve service delivery by increasing the accountability of decision-makers to their clients. This is done by moving decisions closer to the client and introducing a governance structure which allows clients to select [and remove] those local decision-makers. Figure 1 illustrates the new governance structure in education. Figure 1: Governance of Education Under Devolution. *elected **political appointment President Federal Minister of EEducation** Provincial Minister of Education** Secretary of Education Chief Minister of Provincial Government* Provincial Governor** Provincial Assembly* District Coordination Officer Nazim/District Council* Executive District Officer (Ed. & Lit.) Nazim/Tehsil Council* Schools School Management Committees* Nazim/Union Council VOTERS Community Development Boards Under the new political structure, the voter/client of the school has four avenues for expressing her/his views. First, the voter elects members of the SMC, which at present has responsibilities limited to minor school maintenance and supply, although the SMC could assume significantly larger responsibilities in the future. Second, the voter can participate in and help select members of the Community Development Boards [CDB] which do not yet function but which may play an important role in deciding school infrastructure investments. Third, the voter directly elects members of the Union Council who indirectly select the members of the tehsil and district councils. And, fourth, the voter directly elects the members of the provincial assembly who approve the chief minister of the provincial government and indirectly approve the provincial minister of education. While the voter/client has several avenues for expressing her/his voice, there are at least four factors which constrain accountability with respect to education. First, the voter only indirectly elects the district council and the district nazim, who are now the key decision-makers at the local level. Second, both the district and provincial governments are general purpose, so it is difficult to interpret votes; a negative vote may reflect dissatisfaction with one of several sectors. Third, voters have relatively little objective information on the performance of their schools on which to base their votes. And, fourth, the very limited decision-making powers of the school headmaster means that where voters have the most voice the consequences matter least. In sum, until the voter/client has better information and a more direct link to education decision-makers, and until the school headmaster has greater authority and responsibility, devolution is unlikely to significantly improve accountability in Pakistan. MAJOR RISKS AND CHALLENGES. Pakistan has embarked on a radical devolution of government, including the education sector, significantly changing the roles of key actors and levels of government. Fully implementing this devolution would be difficult in any country, especially one facing significant human resource constraints. To be successful in terms of improving educational services and strengthening accountability will require the following: Quickly resolving ambiguities concerning the roles and responsibilities of diverse actors and levels of government. Reengineering and restructuring of the public education bureaucracy at all levels of government. Building capacity to carry out new roles and responsibilities at all levels of government but, especially, at the provincial and district levels. Creating from scratch a system of education finance which ensures equity and provides incentives for improving access and quality. Putting in place a system of real accountability to the beneficiaries and the sources of finance of public education. Creating a system of learning with short feedback loops into policy and practice. Resolving Ambiguities. Ambiguities concerning roles and responsibilities often results in lack of action. In Pakistan, it is clear that key actors in the system are unclear as to their roles and responsibilities under decentralization. To some extent this lack of clarity could be resolved through training and better communication. However, the lack of detailed terms of reference also contributes to ambiguity—in the minds of both educators and government officials—concerning who is responsible for what. [A good example of provincial assistance to reduce ambiguity is the document prepared by the Education Ministry of Sindh for district officials containing terms of reference for the most important education officials within the districts.] Mirroring ambiguities about the duties of education officials are ambiguities concerning the roles and responsibilities of different levels of government. While many responsibilities are in any case shared, there needs to be clarity concerning how those responsibilities are divided and which level of government takes the lead for which functions. Of special concern is ambiguity about which level of government is responsible for ensuring equity, for ensuring learning from experience, and for building capacity. Also, of concern is ambiguity concerning which level of government is responsible for planning, financing, and delivering the in-service and pre-service teacher training so critical to raising the quality of instruction. Another ambiguity not resolved in current devolution plans is the role of the teacher unions. Unions have in the past successfully fought back attempts to increase parental participation in school governance. While their voice is currently suppressed, there is no reason to expect that their views and opposition to devolution have changed substantially. Thus, unless the unions are involved in the devolution dialogue, it is likely that they will become obstacles to devolution once the political scene is liberalized. Reengineering the Bureacracy. To the extent the responsibilities and functions of different levels of government have changed, there is a need to reengineer and restructure the public education bureaucracy. While the need is obvious at the district level, it is at least as important at the provincial level. Provincial ministries are designed to manage a large and complex bureaucracy, but they no longer have much responsibility for day to day management of the system. They now should have a different mission—to guide, motivate, and facilitate actions by district governments and district level officials to deliver education services equitably, efficiently, and of adequate quality. The tools to carry out this mission are those of financial incentives, setting standards, providing technical assistance, and providing information to district officials and the public alike. The capacity to design the policies and procedures to make these tools effective is by and large lacking at present in education ministries, although some of this capacity does exist in the autonomous education foundations (e.g., the Sindh Education Foundation) and NGO and university think tanks with close ties to government. Building Capacity. While the provincial education ministries need to be reengineered, far more important than the organograms and mission statements of those ministries is the human resource capacity to carry out the new functions. Similarly, at the district level there is the need to create the capacity to plan and manage budgets and human resources that their new functions require. In the short-run, the lack of capacity is addressed by the districts in part through relying on incremental budgeting [where the FY03 budget is determined by adding 10 to the FY02 budget categories]. And at the level of the school there is the need to create the capacity for citizens to effectively participate in the governance, and in some cases management, of the schools. While much of this capacity needs to be developed within the education sector, the lack of capacity outside the sector—e.g., in district budgeting and financial management—can also adversely affect the sector. Building capacity will require a comprehensive and sustained effort that not only imparts new skills but, also, changes values and behaviors. Short term training courses are unlikely to have much real impact. Rather, the national and provincial education ministries should be developing permanent programs for increasing capacity and, also, should be working with district governments to develop district-level training programs for district staff and citizens involved with the management and governance of the sector. Ensuring Adequate Education Finance. The new system of intergovernmental finance in Pakistan calls for education being financed from three sources: district government own-source revenues, provincial non-earmarked block grants to the districts, and ad hoc federal education grants to the provinces and districts (e.g., the money transferred under the ESR). This system ensures neither equity nor adequate financing for education in a country where many primary school age children still lack access to school, where the quality of schooling is deficient, and where the poor and girls lack equitable access. The multiple objectives of education finance require multiple instruments. Either the national and/or provincial governments should introduce standards for minimum quality of education and create the financial mechanism to ensure every district has an education budget adequate to meet those standards. There are several intergovernmental finance models which Pakistan could draw on for ideas, including the Brazilian model of Federal transfers to ensure minimum spending per pupil and the US model of state/provincial transfers to do the same. In addition to ensuring adequate spending per pupil to meet minimum education standards, there is a need to provide incentives to districts to rapidly increase coverage, something which provincial block grants to districts do not do. These incentives could be in the form of capitation funding formulas or “contracts” with communities to create and manage their own schools, which may mean expanding the scope of the mission of the provincial education foundations. Finally, there is the need to ensure that specific groups—the poor, girls, ethnic or tribal groups—have adequate access to schooling through the creation and financing of special programs addressed to these specific groups. In the case of the poor, the special program may be a stipend paid to poor families to send children to school. In the case of girls, the program may be scholarships to attend private girls’ schools. In the case of ethnic or tribal groups, the program may be the creation of bilingual curriculum or training of bilingual teachers. In most federal countries, programs to meet the needs of special groups typically fall under the purview of the national government, although progressive provincial governments may initiate their own policies and programs to meet these equity goals. Creating Real Accountability. For real accountability, the consumers/beneficiaries of educational services and those who supply the financing for education require information on the outcomes and uses of funds and need mechanisms to provide incentives for good performance. This implies that they need “voice”, or the means to express their views and they need mechanisms to reward good performance and penalize bad performance. These ingredients in the recipe for accountability are by and large lacking. The consumers of public education in Pakistan have great difficulty in finding information on the outcomes of schooling. Information on student learning, for example, is not available at the level of the district, much less the level of the school or the individual student. Parents have a newly found “voice” in their ability to vote for school management councils and local and provincial public officials. However, the linkage between the election of public officials and educational performance is dubious. Creating Learning. There are no recipes for the implementation of a decentralized educational system that efficiently produces quality education with equity. The historical and cultural context of each country is different, which means that the appropriate model of decentralization and the best implementation strategy is specific to each country. Also, within each country one can always find examples of ugly failure and great success within the public education system. One of the challenges for government is to quickly learn lessons from these failures and successes so that these lessons may be fed back into fine-tuning the design and implementation strategy. Pakistan needs to carefully monitor both the process and the outcomes of education devolution in order to identify and understand best practice. While it is relatively easy to monitor intermediate measures of outcomes—enrollment rates, teacher attendance, expenditures per pupil, etc.—it is equally important to monitor processes—community participation, decision making practices, the flow of funds, etc.—in order to be able to interpret both unusually good and unusually bad performance. There is no institutionalized mechanism at present, at any level of government, which attempts to do this monitoring and to systematically feed back best practice into the design and implementation of education policy. While this could take place at either the provincial or national level, it is most likely at the national level where the wide variety of Pakistani experience—across provinces and across schools—can best be analyzed, interpreted, and disseminated. Federal Education Sector Reform. The Federal Ministry of Education has initiated a 2001-2004 Action Plan in support of Education Sector Reform [ESR], which has the objective of meeting the long term human development goals of the country as specified in the National Education Policy, the Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper, and the Education for All National Plan of Action. These goals address the low educational attainment, lack of access to schooling, and educational inequities identified earlier in this report. The ESR is also designed to facilitate the country’s process of education devolution through improving information on the performance of the educational system and building local capacity, although these activities represent only 12 percent of the overall projected expenditure of the ESR, which is an add-on to the regular Federal budget for education. The total estimated cost of the ESR Action Plan is $1.05 billion, with about 40 percent of the total to be allocated to primary education. The bulk of ESR expenditure at the level of primary education would be allocated to improving and expanding the physical infrastructure. About 2 percent of ESR expenditure would be allocated to capacity building at the district level. In addition, the ESR would support institutional changes, especially the development of parent-teacher associations, in the Islamabad Capital Territory [ICT]. While the direct support of the ESR for the institution and capacity building required under devolution is relatively small, most of the funding at the levels of primary and technical education would be channeled through the district governments, thus providing an important source of additional education financing.2 Also, the creation under the ESR of a national testing system promises to provide citizens with an important, and until now lacking, source of information concerning the quality of schooling. The Federal Government has by and large left to the provincial governments the responsibility for providing technical assistance and building capacity at the district level and below in the education sector. With the assistance of the Federal Government, the provincial governments have already held provincial and district workshops to identify capacity building requirements.3 Given the facts that the Federal Government through the NRB has initiated the devolution process in Pakistan, that the provincial education bureaucracies cannot be expected to enthusiastically support education devolution, and that the Federal MOE is proactive vis a vis the provinces with respect to other educational objectives, the Federal Government should continue to work with provinces and districts to support the process of devolution. 2 The formula for allocating ESR funds reserves 10 percent of funds for the federally administered special areas; of the remaining 90 percent, 5 percent is allocated each to NWFP and Balochistan and the rest is allocated on the basis of population. The agreement between the Federal and provincial governments stipulates that the provinces will transfer funds onward to district government accounts within two weeks. 3 For example, see the proceedings of the District Social Sector Development Forum, Multan District Government, March 2002. BIBLIOGRAPHY Blood, Peter R. ed. (1995) Pakistan: A Country Study. Area Handbook Series. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress: Washington, D.C. DFID (2002). Draft Project Concept Note II, CIET: Building Accountability for Public Services Through Devolution. Islamabad. Federal Ministry of Education (2001). The Road Ahead: Education Sector Reforms: Action Plan 2001-2004. Islamabad, Pakistan. Sindh Education Foundation (2002). Handbook for District Government Nazims. Karachi, Pakistan, Government of Sindh, Karachi, Pakistan. Government of Balochistan (1994a). Officer Guide: Education Rules and Regulations-Field Staff. Quetta, Balochistan, Directorate of Primary Education. Government of Balochistan (1994b). Officer Guide: Education Rules and Regulations: Directorate Staff. Quetta, Balochistan, Directorate of Primary Education. Hatfield, R. (2001). Management Reform in a Centralized Environment: Primary Education Administration in Balochistan, Paksitan 1992-1997. London School of Economics and Political Science, London. Jatoi, I. and H. Jatoi (1994). District Education Offices in NWFP: Work Expected, Actual and Ideal. Peshawar, Pakistan, Directorate of Primary Education, NWFP: 62. Khan, S. R. and F. Zafar (1999). Capacity Building and Training of School Management Committees. Sustainable Development Policy Institute: Islamabad, Pakistan. Manor, J. (1999). The Political Economy of Democratic Decentralization. Washington, D.C., The World Bank. Matthews, P. W. (1995). The Management of Elementary Education in Punjab--First Report. Lahore, Pakistan, Department of Education, Government of Punjab. Multi-Donor Support Unit [MSU] (2001a). Devolution and Decentralization: Implications for the Education Sector: Balochistan. Provincial (Balochistan) Workshop Report, Quetta, Pakistan. MSU (2001b). Devolution and Decentralization: Implications for the Education Sector: NWFP. Provincial (NWFP) Workshop Report, Peshawar, Pakistan. MSU (2001c). Devolution and Decentralization: Implications for the Education Sector: Punjab. Provincial (Punjab) Workshop Report, Lahore, Pakistan. MSU (2001d). Devolution and Decentralization: Implications for the Education Sector: Sindh. Provincial (Sindh) Workshop Report, Sukkur, Pakistan. MSU (2001e). Devolution and Decentralization: Implications for the Education Sector. National Technical Group Meeting, Islamabad, Pakistan. Williams, James H.(2001). "School Quality and Attainment in developing Countries". Paper presented at UNHCR workshop on "Refugee Education in Developing Countries: Policy and Practice. Washington, D.C. Winkler, Donald R. and Alec Ian Gershberg (2000). "Education Decentralization in Latin America: The Effects on the Quality of Schooling". LCSHD Paper Series No. 59. Human Development Department, The World Bank: Washington, D.C. Zaidi, S. and S. Hunt (1998). Education Sector Performance in the 1990s--Pakistan Integrated Household Survey. Islamabad, Pakistan, Federal Bureau of Statistics, Government of Pakistan. ANNEX I: Punjab: Structure of the Education Civil Service Pre-Devolution 1. The senior most positions in the secretariat of the provincial departments of education were members of the Civil Service of Pakistan (CSP). Although nominally under the control of the provincial governments, they were in reality members of various federal government cadres, e.g. the District Management Group (DMG), the accounts cadre, etc. The other senior staff specifically the Section Officers (BPS 17), along with the junior staff (BPS 5-16) were members of the Provincial Secretarial Service. None of the senior or junior staff would expect to stay long in the education departments. 2. While occupying these provincial positions, career concerns of individual staff members focused for the most part on fulfilling the requirements for promotion to more senior positions in their own federal cadre in the province, to senior positions in Islamabad, and even to overseas positions. Such concerns were legitimate, but the result was ambivalence in their functioning, i.e. they could promote policies that favored their federal careers and the Federal Ministry of Education rather than policies that favored the betterment of elementary education in their respective provinces. 3. Further down the chain of command in the provinces, the directors for education and their staff, e.g. divisional and district officers, LCs and teachers, were also under the control of federal civil servants: the Commissioner (for the divisions), the Deputy Commissioner (for the districts), and the Assistant Commissioner (for the tehsils). Additionally, members of the federal accounts cadre had a major role in the financial matters of the districts. 4. Other components of the all-pervasive influence of the federal government over elementary education in Punjab were: a) the division of personnel into classes; e.g. officers, non-gazetted staff (below BPS 16) and Class IV staff (BPS 1-4), b) the salary structure, i.e. the BP 1 to 22 structure with 15 increments per grade in the lower grades and 10 and less increments in the higher grades; c) the inclusion of educational personnel in salary and other structures designed for clerical, administrative and executive personnel; d) the use of ranks rather than positions to classify staff All these were federally determined. Matthews (1995) commented that “On the whole it would be better for elementary education in Punjab if there were fewer (or even no) federal civil servants working in and directly influencing elementary education in Punjab, and if there was a single education service which allowed staff to be more mobile, had its own salary structure related directly to the needs of education personnel, and had a position-based rather than rank-based structure for educational personnel” (Matthews 1995:84) 5. Promotion was strictly by seniority, each cadre having its own seniority list. Hence, in regard to DPI EE staff there were many seniority lists—one for each of the 113 tehsils for primary school teachers, one for each of the thirty four districts for middle school teachers and others for other personnel. 6. While administrative service staff would not be appointed to the DOE, professional, ministerial and Class IV staff would expect to spend their careers in the DOE, PSS staff would expect to be transferred from time to time from one provincial government department to another, while CSP staff (including the DMG group and the Accounts cadre) would expect transfer within and between the departments of the Governments of Pakistan and the provinces. 7. The result of there being gazetted and non-gazetted staff, cadre specific seniority lists and the various transfer possibility was that persons working in the same office could belong to different cadres (and unions, associations and the like) and would not necessarily be committed to the same administrative and managerial ends as each other (p.23). Illustrative of these staffing structures, below is a chart that maps the organization of professional staff positioned within the Punjab Department of Education prior to the LGO 2001. Basic Pay Scale Field Office Punjab Education Professional Staff Hierarchy (Pre-Ordinance)* Positions Recruitment Provincial Secretary of Education (1) 20 & 21 Provincial Director of Public Instruction (Elementary Education) (1) 19 &20 19 & 20 19 & 20 18 18 Provincial Provincial Division Division District Additional Director of Public Instruction (EE) (1) Director of Schools Divisional Director of Education Deputy Divisional Director of Education (EE) District Education Officer (EE) Male and Female Political appointment, civil service (Federal DMG cadre) Professional staff either transferred or promoted from the ranks of professionals in the schools. Promoted from DDEO, secondary school headmaster position or a secondary school subject specialist or transferred from one of these three categories. 17 Tehsil Deputy District Education Officer (EE) Male and Female Have been SSTs and have had 5 years admin. experience, most likely as a Headmaster of a secondary school. 16** Markaz Assistant Education Officer (1,195) At least 5 years experience as a secondary school teacher (SSC). 11 Union Council Learning Coordinators (4,844) PST teachers progress up the seniority list until they reach the top. At that point they are offered the choice of becoming an LC. 9 to 15 Middle Schools Teachers (51,049) Selected after Matric at the end of Class XII. Application process through GCET and award of Cert. of Teaching. Appointed by DEO in the district from which they are recruited. 7 to 11 Primary Schools Teachers (121,492) Selected after Matric, i.e. end of Class X by application process of GCET. Once PSTC*** is awarded, teacher is hired by ed. Officer within the tehsil cadre. *The DOE of Punjab was one of few departments to have staff and offices at all administrative levels from Provincial headquarters to the union councils and even lower to the schools. **Gazetted officers are those in BPS 16 and above and can be in charge of other personnel. ***Primary (School) Teacher Certificate 1.2 Punjab—Ministerial Staff assigned in various work locations, i.e. Secretariat, Division, District, etc. Basic Pay Scale 17 16 16 15 & 16 12 to 14 11 to 15 7 to 10 5 to 6 Class IV Staff: BPS 1-4 Field Office Positions Ministerial Staff BPS 5-17 DOE, Division, District, Tehsil, or Markaz Assistant Director Superintendent Extra Assistant Director Sr. Stenographer Stenographer Assistant Sr. Clerk Jr. Clerk Peons, drivers, daftari, sweeper, chowkidar, etc Recruitment Members of this cadre are recruited directly by the Punjab Public Service Commission for administrative positions in the Education Department. The ranks up which ministerial staff can be promoted are shown in the first column. Staff can be promoted to provincial positions of extra assistant director and assistant director in the province’s divisions and provincial office but no further. Ministerial staff expect to stay in the one department throughout their career. Locally recruited by concerned office. There is no promotion track. 8. Promotion was strictly by seniority, each cadre having its own seniority list. Hence, in regard to Punjab DPI EE staff, for example, there were many seniority lists—one for each of the 113 tehsils for primary school teachers, one for each of the thirty four districts for middle school teachers and others for other personnel. 9. While administrative service staff would not be appointed to the DOE, professional, ministerial and Class IV staff would expect to spend their careers in the DOE, PSS staff would expect to be transferred from time to time from one Government of Punjab department to another, while CSP staff (including the DMG group and the Accounts cadre) would expect transfer within and between the departments of the Governments of Pakistan and Punjab. 10. The result of there being gazetted and non-gazetted staff, cadre specific seniority lists and the various transfer possibility was that persons working in the same office could belong to different cadres (and unions, associations and the like) and would not necessarily be committed to the same administrative and managerial ends as each other (p.23). Work Locations in Punjab falling under Elementary Education (1995) 11. The following division of work levels draws on the pre-Ordinance structure which existed in Pakistan prior to the devolution policy. The designations in the Punjab are illustrative of the multi tier hierarchy: 1. Directorate of Public Instruction—Elementary Education (DPI—EE) The DPI_EE is headed by a Director who is selected on the basis of seniority from among the education professionals. He was responsible to the Secretary of Education for all elementary education activity in Punjab. He is assisted by Additional Director of Public Instruction, three Directors and seven Assistant Directors. These staff were assigned the following responsibilities: Budgeting (both development and non-development budgets; Utilization of funds allocated under the Social Action Program Preparation of submissions for projects Scholarships for elementary education students; Fellowships for elementary education staff; Planning Academic matters Personnel administration (male and female); Filling of vacant positions in the Directorate; Staffing of schools Conducting enquiries and handling minor punishments against teachers; Oversight of recruitment activities (BPS 1-7 for Tehsils; BPS 9-12 for Districts; BPS 15-16 for Divisions; and BPS 17 for the Pakistan Civil Service; Promoting staff BPS 17 and higher Processing applications for transfer (BPS 1-19); Processing of interdivisional transfers; Processing applications of leave outside Pakistan Processing general matters, development, accounts, etc. School management committees Neglected schools and school adoption programs; Conducting surveys and examinations. (1995:68) The DPI-EE is staffed with the establishment of Ministerial Staff and Level IV Staff. 2. Division Each division is headed by the Director of Education (Elementary Education), who is assisted by the Deputy Director of Education. They are supported by Assistant Directors, Ministerial and Grade IV staff. One of the ministerial staff is the registrar (who is the Extra Assistant Director), who assists in conducting Class VIII exams for scholarships and promotion to Class IX throughout the division. The Division Officers’ major tasks are: To manage their own offices and staffs, including hearing complaints; To promote the improvement of education and literacy throughout the division; To approve re-appropriations within the division (a power delegated by the Secretary); To draft the budget for the division office; To ensure that within the division construction of school buildings is actually taking place and to forward progress reports to the DPI EE; To change the approved sites for proposed primary schools if they are of the opinion that it is the wrong place to build a school; To oversee all development projects within the division; To ensure that all schools are following the approved curriculum; To oversee the conduct of all Class VIII examinations and to determine which examinees should get scholarships for Class IX study; To implement incentive programs for teachers; To represent the Government of Punjab in all litigation cases involving teachers and other division staff; To represent the Government of Punjab in all litigation cases about land for schools; Liaise with other departments and agencies in the division; To inspect all DDEOs and some LCs; and To approve requests for interdivisional transfers. (1995:66) 3. District There were 34 districts (plus the Cantonment in Lahore) in Punjab prior to the Ordinance 2000. Each district had two elementary education offices, and each office was headed by a District Education Officer Male (DEO-M) and a District Education Officer Female (DEO-F). In some districts, DEOs were assisted by a Deputy District Education Officer. A person becomes a DEO because through vacancies which he or she are senior enough to qualify. The main tasks of a DEO were: To visit (10 days per month), and supervise the management of mosque, primary, middle, private and municipal (up to middle school) and Department of Social Welfare schools in the district; To supervise the construction, opening and staffing of new schools; To supervise the upgrading of existing schools; To oversee the maintenance of schools; To oversee the various development plans for school buildings and facilities; To select new sites for schools whose premises have been resumed by owners; To ensure that in the schools the teacher are following the approved curriculum; To assist teacher training and improvement; To oversee existing and assist in forming of new school management committees; To select teachers for in-service training; To organize special district wide events and the district component of provincial and national events; To appoint middle school teachers and consolidate the middle school cadre seniority lists an d decide the award of selection grade and transfer of staff; To liaise with other government agencies and local councils in regard to the delivery of educational services. (1995:63) Each District Office was staffed with established Ministerial and Grade IV personnel. 4. Tehsil Each Tehsil had a DDEO F and a DDEO M who were supported by ministerial staff (an assistant and two junior clerks) and by Class IV staff (peon and a driver). The number of schools that DDEOs directly supervised in Punjab ranged from 32 to 835. Their main tasks were: To visit all primary and middle schools in their tehsil in the year (ten working days were to be spent on field visits); To supervise AEOs, PSTs, MSTs and Lcs in their tehsil; To appoint PSTs and Class IV employees; To write the annual confidential reports (ACR) for the AEOs, and the HTs; For DDEO males only to purchase and distribute learning materials for schools. (1995:59) 5. Markaz AEOs were appointed to each Markaz and were responsible for a specific group of schools called a “circle”. In some Markazes there was both an AEO male and and AEO female for supervision of boys and girls schools. Their main activities included: To supervise those primary and middle schools in their “circle” To write ACRs for all primary school teachers and LCs in their “circle”; To collect data as required by the DEO, DE and DPI EE; To inspect and report on the state of repairs of school buildings; To check primary school teacher and student registers; and To encourage parents to send their children to school for compulsory schooling and to encourage adults to become literate. (1995:58) Some AEOs had junior clerks attached to their offices. 6. Union Council Learning Coordinators were posted to each union council and worked with primary school teachers. Their main tasks were: To give demonstration lessons to teachers; To advise on classroom management; To advise teachers on various other educational matters; and To report teacher absenteeism to the AEO. (1995:56) Annex II: NWFP: Structure of the Education Civil Service Basic Pay Scale Pre-Ordinance Structure—NWFP Field Office BPS 20 BPS 20 BPS 18 / 19 BPS 18 / 19 BPS 17 /18 Bps 17 Provincial (Secretariat) Provincial District District District District BPS 16 & 17 District BPS 17 BPS 16 Tehsil Tehsil BPS 11 Union Council BPS 14 Middle Schools BPS 9 Primary Schools Source: Provincial (NWFP) Workshop Report, 2001; (Jatoi 1994) Positions Secretary of Education Director, Primary Education District Education Officer (Male) District Education Officer (Female) Deputy District Education Officers Assistant District Education Officer (Academic) Assistant District Education Officer (Development) Sub-district Education Officers Assistant Sub-district Education Officer (Accounts) Learning Coordinators Teachers Teachers Basic Pay Scale BPS 20 BPS 20 BPS 19 BPS 18 BPS 18 Post- Ordinance Structure—NWFP Field Office Positions Provincial (Secretariat) Secretary of Education Provincial Director, Primary Education &Literacy District Executive District Officer (Education) District District Education Officer (Male) District District Education Officer (Female) BPS 17 Tehsil Deputy District Education Officer BPS 16 BPS 16 Tehsil Tehsil Assistant District Officer Male Assistant District Officer Female BPS 11 Middle Schools Teachers BPS 9 Primary Schools Teachers Provincial (NWFP) Workshop Report, 2001 Note : the post of Learning Coordinators have been abolished a few months ago. Note: Variation between small district layout and large district layout (cite paper plan distributed by NWFP) Work Locations in NWFP under the New Ordinance set-up for Primary Education 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Province : Director, Primary Education District : Executive District Officer ( Schools & Literacy) / District Education Officer ( Primary) Tehsil : Deputy District Education Officer Middle School : CT Teacher (Certificate in Teaching) Primary School : PTC Teacher (Primary Teaching certificate) S Reports to Minis Reports to Secret Reports to Direct Reports to Direct Report to Distric Reports to DEO Report to DEO Report to DEO Reports to DEO Report to ADEO S