Curriculum Outcomes - The University of Edinburgh

PAPER 09/CE/19

A REVISED MODEL FOR THE EDINBURGH MBChB DEGREE BASED ON

LEARNING OUTCOMES (20/11/09)

Outcomes-based education

Outcomes-based education is an approach which has gained acceptance in medical education in recent years. It starts by defining the curriculum Outcomes at the time of graduation. These

Outcomes are defined to match the requirements of medical clinical practice. The curriculum is then aligned to support students in achieving these Outcomes. There are many advantages to such an approach, but perhaps the main one is that students, graduates, employers (the

National Health Service), patients and society have a much clearer statement of what they can expect from medical graduates entering the workplace. Medical schools are then accountable for the degree to which those expectations are met.

An entire issue of “Medical Teacher” was devoted to outcomes-based education in 2007 –

Vol 29, issue 7. For an overview see Harden RM. Outcome-based education; the future is today. Medical Teacher, 2007; 29: 625-629.

Fig 1. A model for an outcomes-based curriculum

Definitions

What is a learning outcome? One attempt to synthesise various definitions states:

“A learning outcome is a written statement of what the successful student/learner is expected to be able to do at the end of the module/course unit, or at qualification.”

( Adam, S., 2004. Using Learning Outcomes. Report for United Kingdom Bologna Seminar

2004, Edinburgh .)

As such there is inevitable confusion with “aims” and with “learning objectives”. In

Edinburgh we have traditionally used “aims” to refer to the highest level, most general statements of what the medical school is trying to achieve. “Objectives” is a somewhat older term which has been used in Edinburgh to describe the detailed, discrete items of learning pertaining to specific learning experiences, such as PBL, lectures, modules, or attachments.

Proposal

In the interests of simplicity, it is proposed to abandon use of the terms “aims” and

“objectives”, and to apply the Adam definition of learning outcomes. The outcomes would constitute a framework going from the highest level, most general MBChB degree outcome

(Level 1) to the most detailed, discrete outcomes for specific components of the curriculum

(Level 5).

How should the outcomes be decided?

Graduating outcomes for a UK medical curriculum can be subject to various influences:

Discussion and negotiation within the Medical School and with NHS partners

The guidance to medical schools from the General Medical Council, "Tomorrow's

Doctors" (2009). The GMC inspects medical schools regularly to establish whether they are following this guidance. The 2009 version for the first time contains an explicit, multi-level Outcomes framework, which has been subjected to very extensive discussion, review and consultation.

“The Scottish Doctor – a competent and reflective practitioner” – published by the

Scottish Deans Medical Education Group after a national consultation process (2002).

It has been very influential world-wide as a model for such approaches.

“The Tuning Project (Medicine) – learning outcomes/competences for undergraduate medical education in Europe” – a consensus statement, based on a Europe-wide survey funded by the European Commission, published by the University of

Edinburgh (2008). Currently the basis of ongoing work on curriculum harmonisation linked to the mandatory mutual recognition of medical degrees in Europe.

There is a growing consensus about the essential outcomes of primary medical degrees and how they are best described and presented, and there is already considerable convergence between these different influences.

At the more detailed levels of the framework, the input from subject representatives within the school, individual teachers, feedback from students, and the context of learning will all play a role in defining what the outcomes should be, and the particular character of the

Edinburgh medical degree programme will be reflected.

Proposal

It is proposed that the Edinburgh curriculum is structured and described in terms of the learning outcomes, and its assessment strategy and framework aligned with that change.

Since the medical school will be accountable for the achievement of the GMC “Tomorrow’s

Doctors” outcomes by all its graduates, and will required in future years to show evidence of this, it seems strategically desirable to use those outcomes as the primary basis for the new structure - albeit with appropriate adjustments and additions to reflect the particular nature and character of the Edinburgh graduate.

TD 2009 specifies 15 major curriculum Outcomes. Experience suggests that this is quite a large number to manage effectively at curriculum level. A very simple adjustment, as shown below (Table 1) reduces the number to 12, and makes alignment with the current Edinburgh structure, the Scottish Doctor, and the Tuning Project more straightforward.

Outcomes as the end-product of curriculum Themes

A simple and logical approach to linking curriculum content to the outcomes is to say that each Outcome is supported by an Outcome Theme. These Themes then encompass the teaching, learning and assessment in all five years of the curriculum. Each Theme has an identified Theme Head, supported by a team of staff active in this area. The assessments related to each Theme accumulate and allow us to be sure that graduates, at the time of graduation, have been adequately assessed in each of the Outcomes.

Levels of outcomes

All existing outcome frameworks have some degree of hierarchical structure, usually referred to as Levels. These are not defined in terms of the importance of the outcomes, but rather the detail of specification, and to some degree, their scope and dimensions.

Proposal

It is proposed that the Edinburgh learning outcomes” are structured in Levels 1-5, with each level being a more detailed break-down and definition of the Level above (Figure 2).

Overarching Degree outcome [1] 1

Role outcomes

[3]

Curriculum outcomes

[12]

Detailed Curriculum outcomes [~60]

2

3

4

Course outcomes

[many]

5

Fig 2 – Levels of outcome in the Edinburgh MBChB degree programme. “Course” is used, as in the rest of the University, to refer to any subdivision of the curriculum such as a module or clinical attachment.

PVTs and KCTs

An important question is how to deal with areas of learning that were separately identified in our previous curriculum structure as “Portfolio Vertical Themes” or “Key Clinical Topics”, but which would not figure overtly in the Level 3 outcomes. Examples include pain, disability, nutrition, life cycle, and clinical conditions such as diabetes. Other than the rather vague label of “topic” ( “a general consideration suitable for argument… a matter”:

Chambers Dictionary ) , there is no single descriptive term that will fit all of these conceptually. Pain is primarily a symptom, life cycle is a concept, diabetes is a disease.

However, it is reasonably straightforward to define them in terms of the learning outcomes to be achieved – e.g. the ability to manage pain effectively; understanding of the influence of the life cycle on human health and disease; ability to investigate, diagnose and manage patients with diabetes.

Proposal

It is proposed that these areas of learning are redefined as Level 4 Outcomes.

Clearly they do not all fit neatly under a single Level 3 Outcome and there is inevitably some degree of empiricism involved. In practice however, the important thing is that these areas are clearly identified, and that students learn about them and are assessed – not necessarily the detail of where exactly they are placed in the Outcomes framework. Similarly, such a process should not be interpreted as diminishing the perceived importance of these areas of learning.

At this stage the particular emphasis and character of the Edinburgh curriculum can be reflected in the formulation of the Level 4 outcomes.

The Portfolio would have to move to a slightly less specific remit – effectively it would be a tool for learning and assessment about any and all of the Outcomes, but with a focus on those which lend themselves particularly to portfolio-based learning. Such a structure has already been outlined by Dr Helen Cameron.

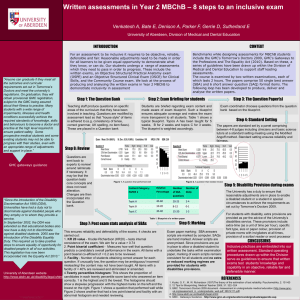

Blueprinting and tracking of Assessment of outcomes

Blueprinting is the process by which the content of an integrated examination is mapped on a matrix grid against the Graduating Programme Outcomes. This allows us to track the assessment of students over time under each Graduating Programme Outcome, and therefore allows us to assure the General Medical Council that our graduates have been adequately assessed in each outcome at the time of graduation. This, in turn, allows the General Medical

Council to enter graduates on the Medical Register and provide them with a provisional license to practise.

The OPAL project

The Level 5 learning outcomes (previously referred to as Learning Objectives), of which there are many, define discrete items of teaching, learning and assessment for the various components of the course – e.g. a lecture, module, or attachment. They will require to be specifically mapped against Level 3 and 4 outcomes. This is currently being undertaken as part of the OPAL Project.

Table 1. Proposed Edinburgh outcomes, with corresponding TD 2009 statements.

EDINBURGH MBChB OUTCOMES

GMC TOMORROW’S DOCTORS 2009

OVERARCHING OUTCOME (For Degree of MBChB; Level 1)

An Edinburgh medical graduate will be a caring, competent, confident, ethical and reflective practitioner, equipped for high personal and professional achievement, able to provide leadership and to analyse complex and uncertain situations, for the benefit of patients.

GMC 7. Medical graduates are tomorrow’s doctors. In accordance with

Good Medical Practice, graduates will make the care of patients their first concern, applying their knowledge and skills in a competent and ethical manner and using their ability to provide leadership and to analyse complex and uncertain situations.

THE DOCTOR AS SCHOLAR AND SCIENTIST (Roles; Level 2)

Ability to apply to medical practice:

1. BIOMEDICAL AND CLINICAL

SCIENCES

(Curriculum outcomes; Level 3)

2. PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF

MEDICINE

GMC 8. Apply to medical practice the biomedical scientific principles, method and knowledge relating to: anatomy, biochemistry, cell biology, genetics, immunology, microbiology, molecular biology, nutrition, pathology, pharmacology and physiology.

GMC 9. Apply psychological principles, method and knowledge to medical practice.

3. SOCIAL SCIENCES AND PUBLIC

HEALTH

4. EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE AND

RESEARCH

GMC 10. Apply psychological principles, method and knowledge to medical practice. GMC 11. Apply to medical practice the principles, method and knowledge of population health and the improvement of health and health care.

GMC 12. Apply scientific method and approaches to medical research.

THE DOCTOR AS PRACTITIONER (Roles; Level 2)

Ability to:

5. Carry out a CONSULTATION WITH A

PATIENT

6. DIAGNOSE AND MANAGE CLINICAL

PRESENTATIONS

7. Undertake CLINICAL

COMMUNICATION

GMC 13. Carry out a consultation with a patient.

GMC 14. Diagnose and manage clinical presentations.

GMC 15. Communicate effectively with patients and colleagues in a medical context.

8. Carry out EMERGENCY CARE, FIRST

AID, RESUSCITATION AND PRACTICAL

PROCEDURES

GMC 16. Provide immediate care in medical emergencies.GMC 18. Carry out practical procedures safely and effectively.

GMC 17. Prescribe drugs safely, effectively and economically.

9. Apply principles and knowledge of

PHARMACOLOGY AND THERAPEUTICS, including prescribing.

10. Apply principles and knowledge of

MEDICAL INFORMATICS

GMC 19. Use information effectively in a medical context.

THE DOCTOR AS PROFESSIONAL (Roles; Level 2)

Ability to:

11. Apply principles and knowledge of

MEDICAL ETHICS, LEGAL AND

PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITIES

GMC 20. Behave according to ethical and legal principles.

12. Demonstrate PERSONAL AND

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

GMC 21. Reflect, learn and teach others.

GMC 22. Learn and work effectively within a multi-professional team.

GMC 23. Protect patients and improve care.

EXAMPLE LEVEL 4 OUTCOMES d. e. f. g. h.

Level 3: Apply principles and knowledge of pharmacology and therapeutics, including prescribing.

Level 4: a. Establish an accurate drug history, covering both prescribed and other medication. b. c.

Plan appropriate drug therapy for common indications, including pain and distress.

Provide a safe and legal prescription.

Calculate appropriate drug doses and record the outcome accurately.

Provide patients with appropriate information about their medicines.

Access reliable information about medicines.

Detect and report adverse drug reactions.

Demonstrate awareness that many patients use complementary and alternative therapies, the existence and range of these therapies, why patients use them, and how this might affect other types of treatment that patients are receiving.

Professor Allan Cumming

Director of Undergraduate Learning and Teaching, CMVM

20/11/09