Regulation OF BREATHING 2

advertisement

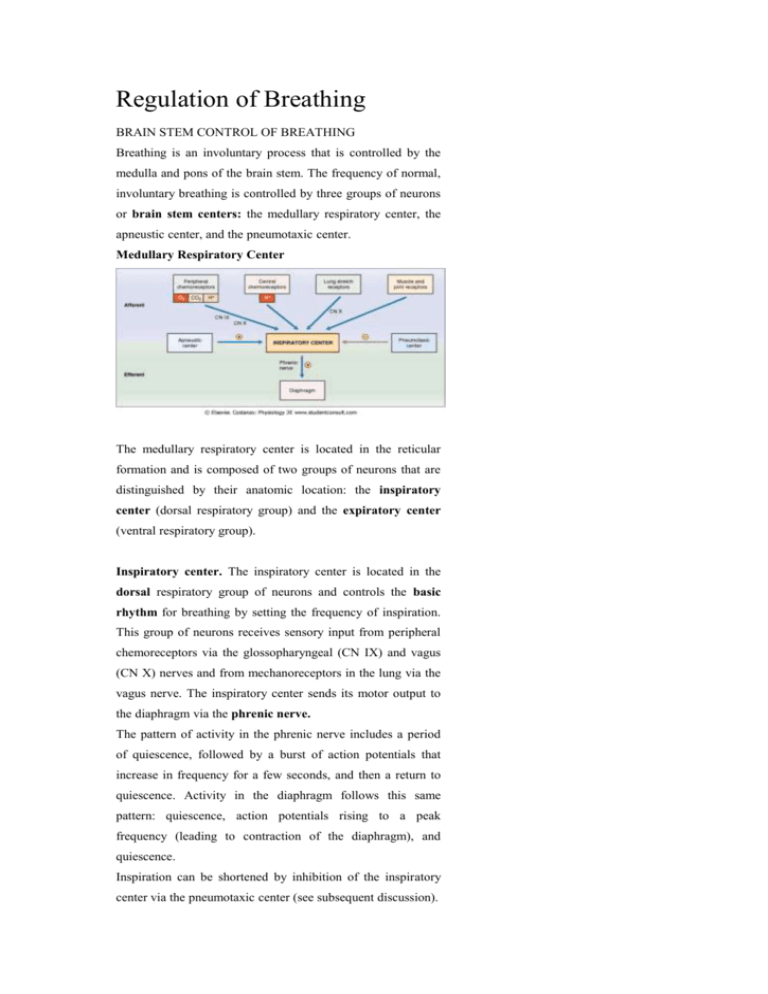

Regulation of Breathing BRAIN STEM CONTROL OF BREATHING Breathing is an involuntary process that is controlled by the medulla and pons of the brain stem. The frequency of normal, involuntary breathing is controlled by three groups of neurons or brain stem centers: the medullary respiratory center, the apneustic center, and the pneumotaxic center. Medullary Respiratory Center The medullary respiratory center is located in the reticular formation and is composed of two groups of neurons that are distinguished by their anatomic location: the inspiratory center (dorsal respiratory group) and the expiratory center (ventral respiratory group). Inspiratory center. The inspiratory center is located in the dorsal respiratory group of neurons and controls the basic rhythm for breathing by setting the frequency of inspiration. This group of neurons receives sensory input from peripheral chemoreceptors via the glossopharyngeal (CN IX) and vagus (CN X) nerves and from mechanoreceptors in the lung via the vagus nerve. The inspiratory center sends its motor output to the diaphragm via the phrenic nerve. The pattern of activity in the phrenic nerve includes a period of quiescence, followed by a burst of action potentials that increase in frequency for a few seconds, and then a return to quiescence. Activity in the diaphragm follows this same pattern: quiescence, action potentials rising to a peak frequency (leading to contraction of the diaphragm), and quiescence. Inspiration can be shortened by inhibition of the inspiratory center via the pneumotaxic center (see subsequent discussion). Expiratory center. The expiratory center (not shown in Fig. 5-30) is located in the ventral respiratory neurons and is responsible primarily for expiration. Since expiration is normally a passive process, these neurons are inactive during quiet breathing. However, during exercise when expiration becomes active, this center is activated. Apneustic Center Apneusis is an abnormal breathing pattern with prolonged inspiratory gasps, followed by brief expiratory movement. Stimulation of the apneustic center in the lower pons produces this breathing pattern in experimental subjects. Stimulation of these neurons apparently excites the inspiratory center in the medulla, prolonging the period of action potentials in the phrenic nerve, and thereby prolonging the contraction of the diaphragm. The pneumotaxic center turns off inspiration, limiting the burst of action potentials in the phrenic nerve. In effect, the pneumotaxic center, located in the upper pons, limits the size of the tidal volume, and secondarily, it regulates the respiratory rate. A normal breathing rhythm persists in the absence of this center. CEREBRAL CORTEX Commands from the cerebral cortex can temporarily override the automatic brain stem centers. For example, a person can voluntarily hyperventilate (i.e., increase breathing frequency and volume). The consequence of hyperventilation is a decrease in PaCO2, which causes arterial pH to increase. Hyperventilation is self-limiting, however, because the decrease in PaCO2 will produce unconsciousness and the person will revert to a normal breathing pattern. Although more difficult, a person may voluntarily hypoventilate (i.e., breath-holding). Hypoventilation causes a decrease in PaO2 and an increase in PaCO2, both of which are strong drives for ventilation. A period of prior hyperventilation can prolong the duration of breath-holding. CHEMORECEPTORS The brain stem controls breathing by processing sensory (afferent) information and sending motor (efferent) information to the diaphragm. Of the sensory information arriving at the brain stem, the most important is that concerning PaO2, PaCO2, and arterial pH. Central Chemoreceptors The central chemoreceptors, located in the brain stem, are the most important for the minute-to-minute control of breathing. These chemoreceptors are located on the ventral surface of the medulla, near the point of exit of the glossopharyngeal (CN IX) and vagus (CN X) nerves and only a short distance from the medullary inspiratory center. Thus, central chemoreceptors communicate directly with the inspiratory center. The brain stem chemoreceptors are exquisitely sensitive to changes in the pH of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Decreases in the pH of CSF produce increases in breathing rate (hyperventilation), and increases in the pH of CSF produce decreases in breathing rate (hypoventilation). The medullary chemoreceptors respond directly to changes in the pH of CSF and indirectly to changes in arterial PCO2 (Fig. 5-31). The circled numbers in the figure correspond with the following steps: 1. In the blood, CO2 combines reversibly with H2O to form H+ and HCO3- by the familiar reactions. Because the blood-brain barrier is relatively impermeable to H+ and HCO3-, these ions are trapped in the vascular compartment and do not enter the brain. CO2, however, is quite permeable across the bloodbrain barrier and enters the extracellular fluid of the brain. 2. CO2 also is permeable across the brain-CSF barrier and enters the CSF. 3. In the CSF, CO2 is converted to H+ and HCO3-. Thus, increases in arterial PCO2 produce increases in the PCO2 of CSF, which results in an increase in H+ concentration of CSF (decrease in pH). 4 and 5. The central chemoreceptors are in close proximity to CSF and detect the decrease in pH. A decrease in pH then signals the inspiratory center to increase the breathing rate (hyperventilation). In summary, the goal of central chemoreceptors is to keep arterial PCO2 within the normal range, if possible. Thus, increases in arterial PCO2 produce increases in PCO2 in the brain and the CSF, which decreases the pH of the CSF. A decrease in CSF pH is detected by central chemoreceptors for H+, which instruct the inspiratory center to increase the breathing rate. When the breathing rate increases, more CO2 will be expired and the arterial PCO2 will decrease toward normal. Peripheral Chemoreceptors There are peripheral chemoreceptors for O2, CO2, and H+ in the carotid bodies located at the bifurcation of the common carotid arteries and in the aortic bodies above and below the aortic arch (see Fig. 5-30). Information about arterial PO2, PCO2, and pH is relayed to the medullary inspiratory center via CN IX and CN X, which orchestrates an appropriate change in breathing rate. Each of the following changes in arterial blood composition is detected by peripheral chemoreceptors and produces an increase in breathing rate: Decreases in arterial PO2. The most important responsibility of the peripheral chemoreceptors is to detect changes in arterial PO2. Surprisingly, however, the peripheral chemoreceptors are relatively insensitive to changes in PO2: They respond when PO2 decreases to less than 60 mm Hg. Thus, if arterial PO2 is between 100 mm Hg and 60 mm Hg, the breathing rate is virtually constant. However, if arterial PO2 is less than 60 mm Hg, the breathing rate increases in a very steep and linear fashion. In this range of P O2, chemoreceptors are exquisitely sensitive to O2; in fact, they respond so rapidly that the firing rate of the sensory neurons may change during a single breathing cycle. Increases in arterial PCO2. The peripheral chemoreceptors also detect increases in PCO2, but the effect is less important than their response to decreases in PO2. Detection of changes in PCO2 by the peripheral chemoreceptors also is less important than detection of changes in PCO2 by the central chemoreceptors. Decreases in arterial pH. Decreases in arterial pH cause an increase in ventilation, mediated by peripheral chemoreceptors for H+. This effect is independent of changes in the arterial PCO2 and is mediated only by chemoreceptors in the carotid bodies (not by those in the aortic bodies). Thus, in metabolic acidosis, in which there is decreased arterial pH, the peripheral chemoreceptors are stimulated directly to increase the ventilation rate. OTHER RECEPTORS In addition to chemoreceptors, several other types of receptors are involved in the control of breathing, including lung stretch receptors, joint and muscle receptors, irritant receptors, and juxtacapillary (J) receptors. Lung stretch receptors. Mechanoreceptors are present in the smooth muscle of the airways. When stimulated by distention of the lungs and airways, mechanoreceptors initiate a reflex decrease in breathing rate called the Hering-Breuer reflex. The reflex decreases breathing rate by prolonging expiratory time. Joint and muscle receptors. Mechanoreceptors located in the joints and muscles detect the movement of limbs and instruct the inspiratory center to increase the breathing rate. Information from the joints and muscles is important in the early (anticipatory) ventilatory response to exercise. Irritant receptors. Irritant receptors for noxious chemicals and particles are located between epithelial cells lining the airways. Information from these receptors travels to the medulla via CN X and causes a reflex constriction of bronchial smooth muscle and an increase in breathing rate. J receptors. Juxtacapillary (J) receptors are located in the alveolar walls and, therefore, are near the capillaries. Engorgement of pulmonary capillaries with blood and increases in interstitial fluid volume may activate these receptors and produce an increase in the breathing rate. For example, in left-sided heart failure, blood "backs up" in the pulmonary circulation, and J receptors mediate a change in breathing pattern, including rapid shallow breathing and dyspnea (difficulty in breathing). Integrative Functions Examples are the responses to exercise and the adaptation to high altitude and. RESPONSES TO EXERCISE The response of the respiratory system to exercise is remarkable. As the body's demand for O2 increases, more O2 is supplied by increasing the ventilation rate: Excellent matching occurs between O2 consumption, CO2 production, and the ventilation rate. For example, when a trained athlete is exercising, his O2 consumption may increase from its resting value of 250 mL/min to 4000 mL/min, and his ventilation rate may increase from 7.5 L/min to 120 L/min. Both O2 consumption and ventilation rate increase more than 15 times the resting level! An interesting question is What factors ensure that the ventilation rate will match the need for O2? At this time, there is no completely satisfactory answer to this question. P50. A significant point on the O2-hemoglobin dissociation curve is the P50. By definition, P50 is the PO2 at which hemoglobin is 50% saturated (i.e., where two of the four heme groups are bound to O2). A change in the value of P50 is used as an indicator for a change in affinity of hemoglobin for O2. An increase in P50 reflects a decrease in affinity, and a decrease in P50 reflects an increase in affinity. Remarkably, mean values for arterial PO2 and PCO2 do not change during exercise. An increased ventilation rate and increased efficiency of gas exchange ensure that there is neither a decrease in arterial PO2 nor an increase in arterial PCO2. (The arterial pH may decrease, however, during strenuous exercise because the exercising muscle produces lactic acid. Recalling that the peripheral and central chemoreceptors respond, respectively, to changes in Pa O2 and PaCO2, it is a mystery, therefore, how the ventilation rate can be altered so precisely to meet the increased demand when these parameters seem to remain constant. One hypothesis states that although mean values of arterial PO2 and PCO2 do not change, oscillations in their values do occur during the breathing cycle. These oscillatory changes may, via the chemoreceptors, produce such immediate adjustments in ventilation that mean values in arterial blood remain constant. Venous PCO2 The PCO2 of mixed venous blood must increase during exercise because skeletal muscle is adding more CO2 than usual to venous blood. However, since mean arterial P CO2 does not increase, the ventilation rate must increase sufficiently to rid the body of this excess CO2 (i.e., the "extra" CO2 is expired by the lungs and never reaches systemic arterial blood). Muscle and Joint Receptors Muscle and joint receptors send information to the medullary inspiratory center and participate in the coordinated response to exercise. These receptors are activated early in exercise, and the inspiratory center is commanded to increase the ventilation rate. Cardiac Output and Pulmonary Blood Flow Cardiac output increases during exercise to meet the tissues' demand for O2. Since pulmonary blood flow is the cardiac output of the right heart, pulmonary blood flow increases. There is a decrease in pulmonary resistance associated with perfusion of more pulmonary capillary beds, which also improves gas exchange. As a result, pulmonary blood flow becomes more evenly distributed throughout the lungs, and the ratio becomes more "even," producing a decrease in the physiologic dead space. O2-Hemoglobin Dissociation Curve During exercise, the O2-hemoglobin dissociation curve shifts to the right. There are multiple reasons for this shift, including increased tissue PCO2, decreased tissue pH, and increased temperature. The shift to the right is advantageous, of course, since it is associated with an increase in P50 and decreased affinity of hemoglobin for O2, making it easier to unload O2 in the exercising skeletal muscle. ADAPTATION TO HIGH ALTITUDE Ascent to high altitude is one of several causes of hypoxemia. The respiratory responses to high altitude are the adaptive adjustments a person must make to the decreased P O2 in inspired and alveolar air. The decrease in PO2 at high altitudes is explained as follows: At sea level, the barometric pressure is 760 mm Hg; at 18,000 feet above sea level, the barometric pressure is one-half that value, or 380 mm Hg. To calculate the PO2 of humidified inspired air at 18,000 feet above sea level, correct the barometric pressure of dry air by the water vapor ressure of 47 mm Hg, then multiply by the fractional concentration of O2, which is 21%. Thus, at 18,000 feet, PO2 = 70 mm Hg ([380 mm Hg - 47 mm Hg] × 0.21 = 70 mm Hg). A similar calculation for pressures at the peak of Mount Everest yields a PO2 of inspired air of only 47 mm Hg! Despite severe reductions in the PO2 of both inspired and alveolar air, it is possible to live at high altitudes if the following adaptive responses occur: Hyperventilation The most significant response to high altitude is hyperventilation, an increase in ventilation rate. For example, if the alveolar PO2 is 70 mm Hg, then arterial blood, which is almost perfectly equilibrated, also will have a P O2 of 70 mm Hg, which will not stimulate peripheral chemoreceptors. However, if alveolar PO2 is 60 mm Hg, then arterial blood will have a PO2 of 60 mm Hg, in which case the hypoxemia is severe enough to stimulate peripheral chemoreceptors in the carotid and aortic bodies. In turn, the chemoreceptors instruct the medullary inspiratory center to increase the breathing rate. A consequence of the hyperventilation is that "extra" CO2 is expired by the lungs and arterial PCO2 decreases, producing respiratory alkalosis. However, the decrease in PCO2 and the resulting increase in pH will inhibit central and peripheral chemoreceptors and offset the increase in ventilation rate. These offsetting effects of CO2 and pH occur initially, but within several days HCO3- excretion increases, HCO3- leaves the CSF, and the pH of the CSF decreases toward normal. Thus, within a few days, the offsetting effects are reduced and hyperventilation resumes. The respiratory alkalosis that occurs as a result of ascent to high altitude can be treated with carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g., acetazolamide ). These drugs increase HCO3- excretion, creating a mild compensatory metabolic acidosis. Polycythemia Ascent to high altitude produces an increase in red blood cell concentration (polycythemia) and, as a consequence, an increase in hemoglobin concentration. The increase in hemoglobin concentration means that the O2-carrying capacity is increased, which increases the total O2 content of blood in spite of arterial PO2 being decreased. Polycythemia is advantageous in terms of O2 transport to the tissues, but it is disadvantageous in terms of blood viscosity. The increased concentration of red blood cells increases blood viscosity, which increases resistance to blood flow. The stimulus for polycythemia is hypoxemia, which increases the synthesis of erythropoietin in the kidney. Erythropoietin acts on bone marrow to stimulate red blood cell production. Clinical uses and unwanted effects One of the most interesting features of the body's adaptation to high altitude is an increased synthesis of 2,3-DPG by red blood cells. The increased concentration of 2,3-DPG causes the O2 hemoglobin dissociation curve to shift to the right. This right shift is advantageous in the tissues, since it is associated with increased P50, decreased affinity, and increased unloading of O2. However, the right shift is disadvantageous in the lungs because it becomes more difficult to load the pulmonary capillary blood with O2. Pulmonary Vasoconstriction At high altitude, alveolar gas has a low Po2, which has a direct vasoconstricting effect on the pulmonary vasculature (i.e., hypoxic vasoconstriction). As pulmonary vascular resistance increases, pulmonary arterial pressure also must increase to maintain a constant blood flow. The right ventricle must pump against this higher pulmonary arterial pressure and may hypertrophy in response to the increased afterload. Acute Altitude Sickness The initial phase of ascent to high altitude is associated with a constellation of complaints, including headache, fatigue, dizziness, nausea, palpitations, and insomnia. The symptoms are attributable to the initial hypoxia and respiratory alkalosis, which abate when the adaptive responses are established. Hypoxemia and Hypoxia Hypoxemia is defined as a decrease in arterial P O2. Hypoxia is defined as a decrease in O2 delivery to, or utilization by, the tissues. Hypoxemia is one cause of tissue hypoxia, although it is not the only cause. High altitude Hypoventilation Diffusion defects V/Q defects Right-to-left shunts HYPOXIA Table 5-6. Causes of Hypoxia Cause Mechanism PaO2 ↓ Cardiac output ↓ Blood flow - Hypoxemia ↓ PaO2 ↓ ↓ O2 saturation of hemoglobin ↓ O2 content of blood Anemia ↓ Hemoglobin concentration - ↓ O2 content of blood Carbon monoxide poisoning ↓ O2 content of blood Left shift of O2-hemoglobin curve - Cyanide poisoning ↓ O2 utilization by tissues - Hypoxia is decreased O2 delivery to the tissues. Since O2 delivery is the product of cardiac output and O2 content of blood, hypoxia is caused by decreased cardiac output (blood flow) or decreased O2 content of blood. Recall that O2 content of blood is determined primarily by the amount O2hemoglobin. Causes of hypoxia are summarized in Table 5-6. A decrease in cardiac output and a decrease in regional (local) blood flow are self-evident causes of hypoxia. Hypoxemia (due to any cause; see Table 5-5) is a major cause of hypoxia. The reason that hypoxemia causes hypoxia is that a PaO2 of less than 60 mm Hg reduces the percent saturation of hemoglobin (see Fig. 5-20). O2-hemoglobin is the major form of O2 in blood; thus, a decrease in the amount of O2hemoglobin means a decrease in total O2 content. Anemia, or decreased hemoglobin concentration, also decreases the amount of O2-hemoglobin in blood. Carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning causes hypoxia because CO occupies binding sites on hemoglobin that normally are occupied by O2; thus, CO decreases the O2 content of blood. Cyanide poisoning interferes with O2 utilization of tissue; it is one cause of hypoxia that does not involve decreased blood flow or decreased O2 content of blood. Summary Lung volumes and capacities are measured with a spirometer (except for those volumes and capacities that include the residual volume). Dead space is the volume of the airways and lungs that does not participate in gas exchange. Anatomic dead space is the volume of conducting airways. Physiologic dead space includes the anatomic dead space plus those regions of the respiratory zone that do not participate in gas exchange. The alveolar ventilation equation expresses the inverse relationship between PACO2 and alveolar ventilation. The alveolar gas equation extends this relationship to predict PAO2. In quiet breathing, respiratory muscles (diaphragm) are used only for inspiration; expiration is passive. Compliance of the lungs and the chest wall is measured as the slope of the pressure-volume relationship. As a result of their elastic forces, the chest wall has a tendency to spring out, and the lungs have a tendency to collapse. At FRC, these two forces are exactly balanced, and intrapleural pressure is negative. Compliance of the lungs increases in emphysema and with aging. Compliance decreases in fibrosis and when pulmonary surfactant is absent. Surfactant, a mixture of phospholipids produced by type II alveolar cells, reduces surface tension so that the alveoli can remain inflated despite their small radii. Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome occurs when surfactant is absent. Airflow into and out of the lungs is driven by the pressure gradient between the atmosphere and the alveoli and is inversely proportional to the resistance of the airways. Stimulation of β2-adrenergic receptors dilates the airways, and stimulation of cholinergic muscarinic receptors constricts the airways. Diffusion of O2 and CO2 across the alveolar/pulmonary capillary barrier is governed by Fick's law and driven by the partial pressure difference of the gas. Mixed venous blood enters the pulmonary capillaries and is "arterialized" as O2 is added to it and CO2 is removed from it. Blood leaving the pulmonary capillaries will become systemic arterial blood. Diffusion-limited gas exchange is illustrated by CO and by O2 in fibrosis or strenuous exercise. Perfusion-limited gas exchange is illustrated by N2O, CO2, and O2 under normal conditions. O2 is transported in blood in dissolved form and bound to hemoglobin. One molecule of hemoglobin can bind four molecules of O2. The sigmoidal shape of the O2hemoglobin dissociation curve reflects increased affinity for each successive molecule of O2 that is bound. Shifts to the right of the O2-hemoglobin dissociation curve are associated with decreased affinity, increased P50, and increased unloading of O2 in the tissues. Shifts to the left are associated with increased affinity, decreased P50, and decreased unloading of O2 in the tissues. CO decreases the O2-binding capacity of hemoglobin and causes a shift to the left. CO2 is transported in blood in dissolved form, as carbaminohemoglobin, and as HCO3-. HCO3- is produced in red blood cells from CO2 and H2O, catalyzed by carbonic anhydrase. HCO3- is transported in the plasma to the lungs where the reactions occur in reverse to regenerate CO2, which then is expired. Pulmonary blood flow is the cardiac output of the right heart, and it is equal to the cardiac output of the left heart. Pulmonary blood flow is regulated primarily by P AO2, with alveolar hypoxia producing vasoconstriction. Pulmonary blood flow is unevenly distributed in the lungs of a person who is standing: Blood flow is lowest at the apex of the lung and highest at the base. Ventilation is similarly distributed, although regional variations in ventilatory rates are not as great as for blood flow. Thus, V/Q is highest at the apex of the lung and lowest at the base, with an average value of 0.8. Where V/Q is highest, PaO2 is highest and PaCO2 is lowest. V/Q defects impair gas exchange. If ventilation is decreased relative to perfusion, then PaO2 and PaCO2 will approach their values in mixed venous blood. If perfusion is decreased relative to ventilation, then PAO2 and PACO2 will approach their values in inspired air. Breathing is controlled by the medullary respiratory center, which receives sensory information from central chemoreceptors in the brain stem, from peripheral chemoreceptors in the carotid and aortic bodies, and from mechanoreceptors in the lungs and joints. Central chemoreceptors are sensitive primarily to changes in the pH of CSF, with decreases in pH causing hyperventilation. Peripheral chemoreceptors are sensitive primarily to O2, with hypoxemia causing hyperventilation. During exercise, the ventilation rate and cardiac output increase to match the body's needs for O2 so that mean values for PaO2 and PaCO2 do not change. The O2-hemoglobin dissociation curve shifts to the right as a result of increased tissue PCO2, increased temperature, and decreased tissue pH. At high altitude, hypoxemia results from the decreased PO2 of inspired air. Adaptive responses to hypoxemia include hyperventilation, respiratory alkalosis, pulmonary vasoconstriction, polycythemia, increased 2,3-DPG production, and a right shift of the O2-hemoglobin dissociation curve. Hypoxemia, or decreased PaO2, is caused by high altitude, hypoventilation, diffusion defects, V/Q defects, and right-to-left shunts. Hypoxia, or decreased O2 delivery to tissues, is caused by decreased cardiac output or decreased O 2 content of blood. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) DESCRIPTION OF CASE. A 65-year-old man has smoked 2 packs of cigarettes a day for more than 40 years. He has a long history of producing morning sputum, cough, and progressive shortness of breath on exertion (dyspnea). For the past decade, each fall and winter he has had bouts of bronchitis with dyspnea and wheezing, which have gradually worsened over the years. When admitted to the hospital, he is short of breath and cyanotic. He is barrel-chested. His breathing rate is 25 breaths/min, and his tidal volume is 400 mL. His vital capacity is 80% of the normal value for a man his age and size, and FEV1 is 60% of normal. The following arterial blood values were measured (normal values are in parentheses): pH, 7.47 (normal, 7.4) PaO2, 60 mm Hg (normal, 100 mm Hg) PaCO2, 30 mm Hg (normal, 40 mm Hg) Hemoglobin saturation, 90% Hemoglobin concentration, 14 g/L (normal, 15 g/L) EXPLANATION OF CASE. The man's history of smoking and bronchitis suggests severe lung disease. Of the arterial blood values, the one most notably abnormal is the PaO2 of 60 mm Hg. Hemoglobin concentration (14 g/L) is normal, and the percent saturation of hemoglobin of 90% is in the expected range for a PaO2 of 60 mm Hg (see Fig. 5-20). The low value for PaO2 at 60 mm Hg can be explained in terms of a gas exchange defect in the lungs. This defect is best understood by comparing PaO2 (measured as 60 mm Hg) to PAO2 (calculated with the alveolar gas equation). If the two are equal, then gas exchange is normal and there is no defect. If PaO2 is less than PAO2 (i.e., there is an A - a difference), then there is a V/Q defect, with insufficient amounts of O2 being added to pulmonary capillary blood. The alveolar gas equation can be used to calculate PAO2, if the PIO2, PACO2, and respiratory quotient are known. P IO2 is calculated from the barometric pressure (corrected for water vapor pressure) and the percent O2 in inspired air (21%). PACO2 is equal to PaCO2, which is given. The respiratory quotient is assumed to be 0.8. Thus, Since the measured PaO2 (60 mm Hg) is much less than the calculated PAO2 (113 mm Hg), there must be a mismatch of ventilation and perfusion. Some blood is perfusing alveoli that are not ventilated, thereby diluting the oxygenated blood and reducing arterial PO2. The man's PaCO2 is lower than normal because he is hyperventilating and blowing off more CO2 than his body is producing. He is hyperventilating because he is hypoxemic. His PaO2 is just low enough to stimulate peripheral chemoreceptors, which drive the medullary inspiratory center to increase the ventilation rate. His arterial pH is slightly alkaline because his hyperventilation has produced a mild respiratory alkalosis. The man's FEV1 is reduced more than his vital capacity; thus, FEV1/FVC is decreased, which is consistent with an obstructive lung disease in which airway resistance is increased. His barrel-shaped chest is a compensatory mechanism for the increased airway resistance: High lung volumes exert positive traction on the airways and decrease airway resistance; by breathing at a higher lung volume, he can partially offset the increased airway resistance from his disease. TREATMENT. The man is advised to stop smoking immediately. He is given an antibiotic to treat a suspected infection and an inhalant form of albuterol dilate his airways. (a β2 agonist) to