pain commonly

advertisement

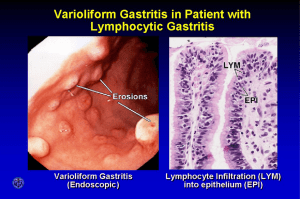

Objectives: i. Discuss the differential diagnosis for epigastric abdominal pain ii. Describe the Physical exam that should occur to evaluate epigastric pain iii. List laboratory studies that should be done to evaluate epigastric abdominal pain. iv. Discuss risk factors for gastric and duodenal ulcers v. Outline an initial treatment plan for H Pylori duodenal ulcer USC Case # 10: Gastritis vs. Ulcer Disease CHIEF COMPLAINT (CC): Epigastric pain. History of Present Illness (HPI): A 45 year old truck driver presents with CC of epigastric and right upper quadrant abdominal pain for the past week. Patient gives a past history of having intermittent, occasional epigastric pain. He states he is a smoker, has been on no medications at this time. He gives a prior history of similar-like symptoms which lasted a shorter time, but eventually went away. He denied any associated fever or cough. What further questions would you ask him next? Have he had any associated chest pain or palpitations? Has he had any associated reflux or prior history of reflux? Has he had any nausea or vomiting? If so, did he have any hematemesis or dark colored emesis? Have his stools changed any? If so, what is the consistency of the stools? Has he had any rectal bleeding? Have the stools been dark and tarry at times? Any associated hematuria or flank pain? Further questioning of his symptoms of epigastric pain should be asked about the following symptoms: 1. Location: Where is the pain and where does it radiate? 2. Quality: What does the pain feel like? 3. Severity: Pain scale 1-10. 4. Timing: When? How long? How frequent is it? 5. Setting: Does it occur at certain times? Related to motion? Food ingestion? 6. Is there any remitting or exacerbating factors? What makes it better or worse? 7. Associated manifestations: Anything else that correlates with the symptom? Patient states the pain is in the epigastric and right upper quadrant. The pain occasionally radiates to his back. The pain is a vague discomfort, also like cramping, hunger pains. On a scale 1-10 it is a 3. It is usually one to three hours after meals. He is also having nocturnal pain which causes early morning awakening at times. The pain was present only one week. It sometimes occurs with stress. The pain is relieved by food (unless he eats spicy food). States he gets occasional heartburn associated but not very bad. Review of symptoms (ROS): Patient states he had had about a two pound weight loss over the last several months. Energy level had been good. Skin: No rashes. HEENT: No complaints. Heart: No chest pains. No palpitations. No shortness of breath. Lungs: No wheezing. No hemoptysis. States he gets an occasional cough because he does smoke. Abdomen: Epigastric and right upper quadrant pain; occasionally has a little back pain with it but no real radiation. States he had had some dark, tarry stools a few times but denied any diarrhea or constipation. States he occasionally had some belching and bloating, abdominal distention, and food intolerance. Denies any flank pain associated. Extremities: No pains. No edema. Back: No lower back pains. Gets occasional pain with the abdominal pain but it is non-specific. Uro: No dysuria. No hematuria. Neuro: No headache, dizziness, or other associated symptoms. Without further investigation, what would your differential diagnosis be? 1. Non-ulcer dyspepsia 2. Duodenal ulcer 3. Gastric ulcer 4. Gastric carcinoma 5. H-Pylori associated gastritis without ulcer 6. Chronic gastritis or acute gastritis 7. Gastroesophageal reflux disease ( with or without Esophagitis) 8. Crohn’s disease 9. Pancreatitis 10. Cholelithiasis syndrome and biliary colic 11. Atrophic gastritis 12. Variant angina pectoris Past Medical History (PMHx): Patient gives a history of smoking cigarettes for about twenty years. States he smokes one pack a day. States he rarely drinks alcohol Past Surgical History: Appendectomy, age 6, without complications. T & A. Family History: Father is living with a history of hypertension. Mother has non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, which has been diet controlled. Social History: The patient is married, has two children, and works as a truck driver. Smokes one pack a day for 25 years. Denies alcohol abuse and rarely drinks alcohol. Has a high school education. Current Medications: None. States he had been taking over-the-counter Tums for the epigastric pain; just gave mild relief. He had been taking some Motrin over-the counter to see if it would help to relieve the pain, which did not seem to help except only for brief period. Physical Exam: General: He is a 45 year old male, alert & oriented x three, pleasant and cooperative. Skin: Warm, moist, pink. HEENT: Within normal limits. Lymph: No lymphadenopathy. Heart: Regular rate & rhythm without murmur. Lungs: Bilateral slight inspiratory crackles; otherwise bilaterally clear to auscultation. Abdomen: Inspection of abdominal wall appears to be normal. Auscultation reveals normal bowel sounds in all four quadrants with no bruits. Percussion notes no organomegaly or masses noted. Palpation elicits very slight pain in the epigastrium and right upper quadrant with palpation with no rebound or guarding. Negative Lloyd’s sign. Negative Murphy’s sign. Extremities: No cyanosis. No edema. Genitourinary: Normal male genitalia. Back: Non-tender. Somatic dysfunction of the T8- neutral. Side bent left. Rotated right. Rectal Exam: No hemorrhoids or masses palpated. Prostate soft. Hemoccult testing positive on one of two fields. Stool appears to be dark brown. Neurologic: A & O x three with no focal deficits seen. You decide to order a further tests to help delineate your diagnosis. You order an EKG to make sure the patient doesn’t have atypical angina pectoris, and appears normal. He gives a history of no pain with exertion, states he hikes without difficulty. You obtain a chest x-ray because he has had a few crackles with a history of smoking, which appears to be normal and clear. You decide to delineate what the patient’s right upper quadrant pain is stemming from. You talk to the patient about ordering an ultrasound. He states he stopped while on the road truck driving and went to emergency room and had an ultrasound done of his abdomen, gallbladder, and liver, which were within normal limits. He says he just forgot about it when he was giving his history. He states at that time they did not do any blood work. You decide to order blood work. What tests would you order at this time to be most cost efficient but to help diagnose the patient’s problem. Lab Work: 1. CBC 2. CMP 3. Urinalysis 4. Amylase/lipase 5. Helicobacter Pylori antibody 6. Hemoccult (already done with physical exam) Current Testing for H Pylori Recommendations: SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ●In patients who do not require endoscopic evaluation for evaluation of new onset dyspepsia (those under age 55 who do not have alarm symptoms), initial diagnosis of H. pylori should be made with a test for active infection (stool antigen or urea breath test). Serology, as it cannot differentiate between past or current infection and has a low positive predictive value in much of the United States, is not recommended in patients with a low pre-test probability. Endoscopic biopsy should be reserved for patients who are undergoing a diagnostic endoscopy and are found to have an ulcer and for those who require endoscopy to follow up a gastric ulcer or for the diagnosis or followup of suspected MALT lymphoma. Biopsy urease testing can be performed in patients not taking antibiotics or a proton pump inhibitor when histopathology is not required. ●We suggest confirmation of eradication because of the availability of accurate, relatively inexpensive, noninvasive tests (stool and breath tests) and because of increased resistance to antibiotic therapy, at least four weeks after treatment (Grade 2B). Uptodate.com You obtain your blood work results from the lab. You note that the CBC has a normal white cell count of 6.7, with normal differential. The patient’s hemoglobin is 11.9, mildly low, with normal MCV at 11.9 with Hematocrit of 35.7, and platelet count of 250,000. The CMP was within normal limits. The amylase and lipase are noted to be normal. The H-Pylori serology is positive. When you further question, the patient states he does remember having the problems in the past (which he didn’t recall earlier); thinks they may have treated him for an infection but he didn’t know what it was or what they gave him. You decide to determine if his serology is positive from past infection with H-Pylori or if he has an active case. You decide to order a confirmatory test. What test would you order? You could order two tests. One is a rapid urea breath test. It has a false negative with recent therapy. But your lab does not perform the urea breath test. You order a stool for H-Pylori antigen, and question the patient if he has been on recent proton pump inhibitors (which may not give you a positive study). The patient states he has not been on the proton pump inhibitors of any type with his history. You order the test, and it comes back positive for H-Pylori. You decide to go through your differential diagnosis list. What diagnosis can you probably rule out at this time. Cholelithiasis syndrome is probably almost absolutely ruled out, as the patient had a negative ultrasound. He gave no history of fatty food intolerance. He probably does not have variant or atypical angina pectoris with EKG normal, and has no symptoms with exertion. His amylase is normal, which would more than likely rule out pancreatitis. He has had no lower quadrant pain, especially right lower quadrant, with no bloody diarrhea, which can probably rule out Crohn’s disease. He does not fit the pattern for atrophic gastritis, which is found more commonly in the elderly as he has had a good appetite, with symptoms increased after he eats rather than when he eats. He has had very mild reflux, but it has not seemed a major problem with him. He has also had no dysphagia or difficulty swallowing, which would most likely rule this out, but still would be within the differential diagnosis. That leaves you non-ulcer dyspepsia, gastric carcinoma, H-Pylori associated gastritis without ulcer, gastroesophageal reflux disease with or without esophagitis, duodenal ulcer, and gastric ulcer. You decide to order further s testing to delineate his diagnosis. You suggest to the patient possibly obtain an upper gastrointestinal barium study for further diagnosis. The patient refuses this, states he has a gastroenterologist who is a friend of his that he would like to see for treatment. You decide to refer him to the gastroenterologist for esophagogastroduodenoscopy. He states his friend can do the EGD the next day in the a.m. Patient was scheduled for the EGD the next a.m., was supposed to be fasting overnight. He has the test done the next morning without complications. The gastroenterologist calls you, about the testing that was done, to give you the diagnosis that he found. He states the esophagus appeared to be normal without irritation or Barrett’s esophagus noted. He states he did not find any carcinoma in the stomach or esophagus. He states he did find an ulcer, and also had a positive rapid urea test indicating H-Pylori. He states his stomach did not appear to have any atrophic gastritis. The gastroenterologist was called to a Code Blue in the Intensive Care Unit and did not get to delineate further whether the ulcer was gastric or duodenal. You try to decide if it is a gastric or duodenal, by the patient’s history, before you get the report from the gastroenterologist. Chronic gastritis was ruled out because endoscopy did not show any abnormality of the gastric mucosa. Chronic gastritis involves one of the four entities; 1. autoimmune atrophic gastritis (type A) 2. Helicobacter gastritis (type B) 3. multifocal atrophic gastritis 4. chemical gastrophy. Acute hemorrhagic gastritis demonstrates widespread petechial hemorrhages. The patient did not show any of these signs on EGD, and were thus ruled out (even though he probably has the possibility of early H. pylori gastritis. Duodenal ulcer occurs four times more commonly than gastric ulcers do. It is more common in men with a 10% lifetime chance in men and a 5% lifetime chance in women for developing a duodenal ulcer. You also note that the predominant age for duodenal ulcer is 25 to 75 years, and gastric ulcer peak incidence is age 55 to 65 years with it being rare under age 40. You note the predominant sex for duodenal ulcer is slightly greater for males than females with gastric ulcer being about equal in males and females with females having more predominance among nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug users. Duodenal ulcer has a more common history of nocturnal pain caused by early morning awakening as compared to gastric ulcer. You note the burning or epigastric pain usually occurs one to three hours after meals with duodenal ulcer, and is often relieved by food. Gastric ulcer is more commonly related with anorexia, food aversion, and weight loss in 40% of the patients. Gastric ulcer also seems to have a greater individual variation for the symptoms. You know that H-Pylori is a major cause of ulcers in the duodenum and gastrium. Gastric acid secretory rates are usually normal or reduced in gastric ulcer, as they are usually increased (slightly) in duodenal ulcer. You know that NSAIDs are associated with both gastric and duodenal ulcer, but seem to be more common with gastric ulcer, but you note that the patient had only taken a small amount of ibuprofen, without daily use. Both may be associated with heartburn, suggesting reflux disease, but this patient only had mild reflux, and had no esophageal changes. The gastroenterologist calls you later on that day to tell you about the ulcer. He states that the H-Pylori is found in nearly 100% of patients with duodenal ulcer and 80% of patients with gastric ulcer. He tells you that the ulcer is associated with H-Pylori and needs to be treated. What area do you think the ulcer was found? Duodenal ulcer. This patient fits classic symptoms for duodenal ulcer. Duodenal ulcer is four times more common than gastric ulcers. They are strongly both associated with use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, having a family history of ulcers, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (gastrinoma), and cigarette use. They also can be associated with use of corticosteroids, with possible genetic predisposition with HLA-B12, B5, BW35 phenotypes. also stress, lower socioeconomic status, and manual labor. It has been poorly associated with dietary spices, alcohol, caffeine, and acetaminophen. The patient did not meet the criteria for Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, as he did not have multiple ulcers, and his duodenal ulcer was found in the duodenal bulb. ZollingerEllison is usually found with multiple ulcers and also distal to the bulb. If you suspect Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, then a gastrin level should be done. Pathologically, the ulcer is usually a greater than 5 mm diameter, and extends through the mucosal linings. Stress related ulcers usually do not penetrate as deep. Imaging studies with upper GI with barium studies are not as accurate and sensitive as endoscopy, and may have false negative or positive procedures. You decide to treat the patient for the H-Pylori and gastric ulcer. What treatments, regimens can you use? Treatment has several different regimens which can be used. Remember to check for drug allergies of your patient before selecting an antibiotic! 1. 2. 3. 4. Triple therapy with bismus subsalicylate plus Metronidazole plus Tetracycline. Ranitidine bismus citrate plus Tetracycline plus Clarithromycin or Metronidazole Omeprazole (Lansoprazole plus Clarithromycin plus Metronidazole or Amoxicillin) Quadruple therapy of Omeprazole (Lansoprazole plus bismus subsalicylate plus Metronidazole plus Tetracycline) 5. Recently, double therapy of Aciphex, plus antibiotics, have been used. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS — Helicobacter pylori treatment is recommended in a number of clinical settings. Multiple treatment regimens exist to treat H. pylori infection (table 1); however, the optimal therapeutic regimen has not yet been defined. (See "Indications and diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori infection", section on 'When to test'.) ●For initial therapy, we suggest triple therapy with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), amoxicillin (1 g twice daily), and clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily) for 10 days to two weeks, if the prevalence of clarithromycin resistance in the population is less than 15 percent (Grade 2B). In the United States, given the limited information on antimicrobial resistance rates, we begin treatment with triple therapy with a PPI, unless antibiotic resistance is suspected. We suggest substitution of amoxicillin with metronidazole (500 mg twice daily) only in penicillinallergic individuals since metronidazole resistance is common and can reduce the efficacy of treatment (Grade 2B). (See 'Triple therapy' above.) ●We suggest quadruple therapy mainly for retreatment (Grade 2B) or as initial treatment in areas where clarithromycin resistance is high (≥15 percent) or in patients with recent or repeated exposure to clarithromycin or metronidazole. Quadruple therapy consists of a proton pump inhibitor twice daily combined with bismuth (525 mg four times daily) and two antibiotics (metronidazole 250 mg four times daily and tetracycline 500 mg four times daily) or with a commercially available combination capsule containing bismuth subcitrate, metronidazole, and tetracycline four times daily for 10 to 14 days. One week of bismuth-based quadruple treatment may suffice for initial therapy as long as it is given with a PPI. (See 'Management of treatment failures' above.) If tetracycline is not available, doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) should be used as a substitute. (See 'Quadruple therapy' above.) ●For patients failing one course of H. pylori treatment, we suggest either an alternate regimen using a different combination of medications as triple therapy or, preferably, quadruple therapy. (Grade 2B). Repeat treatment is influenced by initial treatment. In general, clarithromycin and antibiotics used previously should be avoided if possible. (See 'Management of treatment failures' above.) ●For patients failing two attempts at treatment, compliance with medications should be reinforced. Culture with antibiotic sensitivity testing can be done to guide subsequent treatments. For rescue therapy, we often use levofloxacin (250 mg), amoxicillin (1 g), and a PPI each given twice daily for two weeks. (See 'Management of treatment failures' above.) TABLE 1 American College of Gastroenterology first-line H. pylori regimens (adult dosing, oral administration) Patients who are not allergic to penicillin and have not Standard dose PPI* twice daily (or esomeprazole 40 mg once daily) previously received a macrolide plus clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, and amoxicillin 1000 mg twice daily for 10-14 days• Patients who are allergic to penicillin, and who have not Standard dose PPI twice daily, clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, previously received a macrolide or metronidazole or are unable metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 10-14 days• to tolerate bismuth quadruple therapy Patients who are allergic to penicillin or failed one course Bismuth subsalicylate 525 mg four times daily, metronidazole 250 (above) of H. pylori treatment mg four times daily, tetracycline 500 mg four times daily, standard dose PPI* twice daily for 10-14 daysΔ OR Bismuth subcitrate 420 mg four times daily, metronidazole 375 mg four times daily, tetracycline 375 mg four times daily ◊, standard dose PPI* twice daily for 10-14 daysΔ H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; PPI: proton pump inhibitor. * Lansoprazole 30 mg twice daily, omeprazole 20 mg twice daily, pantoprazole 40 mg twice daily, or rabeprazole 20 mg twice daily. • Eradication rates of 70 to 85 percent. Δ Eradication rates of 75 to 90 percent. ◊ A combination preparation of bismuth subcitrate-metronidazole-tetracycline is available in the United States (trade name Pylera). Upttodate.com _________________ Complications of gastric and duodenal ulcers, when severe, can lead to perforation, which is a medical emergency, and also can lead to gastric outlet obstruction, which should be treated immediately. This patient’s future outlook is good with treatment and avoidance of precipitating factors especially tobacco use and nonsteroidals. The patient was seen in one month follow up with complete resolution of his symptoms. His hemoglobin had returned to normal, he had no more symptoms. Follow up stool studies for H-Pylori antigen were negative three months later (proton pump inhibitors may mask an H-Pylori antigen, and should be stopped at least three weeks prior to checking the stool studies). Readings: Rakel’s Textbook of Family Medicine pp 917 - 920