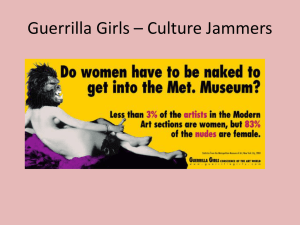

Gender stereotypes denote a difference in how men and women act

advertisement

Gender stereotypes denote a difference in how men and women act, what is considered suitable for each and depicts how they should be (Schmader, Johns, & Barquissau, 2004). For instance, women in society are led to believe that males are paired with performing well on math and science tasks, and women with English and the arts. Although girls and women are closing the gender gap with boys and men in many areas of achievement and interest, research has found that women are still being affected by this gender stereotype. There is also significant research that provides factors that could potentially prevent the gender stereotype threat of women. According to Davies, Spencer, Quinn, & Gerhardstein (2002), females and males are similar in their mathematics and science ability; it is the stereotype threat that can have detrimental effects on women’s academic performance and achievement-related choices. The same stereotype threat can hinder the female from performing to her potential on standardized tests which can determine college and major acceptance and can also persuade the women to stay away from pursuing majors and careers in the science and math domains. Research has also indicated that female’s test performances in the fields of math and science have been significantly lower than males’ performance, hindering women from entering or pursuing a major or career in the math and science field. When entering school, girls start out with higher scores on standardized achievement tests, but in middle school, the scores decrease (Sadker, 1994). Predominantly, research has been performed in the field of math, but the science and math fields are equally lacking women involvement. Articles on gender stereotype threat indicate that factors such as indicating gender on a test, the gender of the experimenter (test-giver), presence of a role model, and gender of the role model have all influenced the results of women’s performance on math tests when compared to men’s. Standardized math tests have been a favorite in many studies as components can be manipulated in a testing environment and results of the test can easily be analyzed and compared. While research has been done with older students, there is also information stating that this begins prior to the age of college and high school and begins in elementary and middle school. Even looking past the standardized scores and enrollment figures, situational and social patterns are evident that support the idea that science and math, and academia in general are aimed at and preferred by the male students. Research taken from classroom observations in the public schools reveals that boys receive more “praise, cues, criticism, encouragement, and eye contact than do their female classmates” (Funk, 2002). In the younger grades, it is shown that teachers call on male students more and they are drawn to male-dominated sections of the classroom (Thorne, 1992). When this lack of interaction with female students occurs in the elementary grades, by the time the girls reach high school, they can attribute failure to their inability, especially in the math and sciences (Barba & Cardinale, (1991). In addition to the attention, males also get more academic concentration such as more types of questions and probing, and also more feedback on their performance (Ricks & Pyke, 1973). This is a huge disappointment and shame because any type of “interaction between the student and the teacher is key to the learning process” and if teachers are not providing this equally, then the female students are suffering educationally and emotionally (Barba & Cardinale, (1991). Given the negative consequences that gender stereotypes have on women’s performance, researchers have been trying to identify ways to protect the performance from being affected by negative stereotypes. Marx and Roman (2002) argue that one way this can be done is by incorporating female role models in the math-related domains. This can be carried over to the science- related domains as well, to cover the two most male stereotyped subjects. Role models are selected by social comparison and all have a common feature that is perceived as competent in a specific area (Marx & Roman, 2002). Individuals, who choose role models, often use them as motivation, to enhance self-evaluation, and as a guide for their aspirations. It is evident from research that intelligence and ability are not the reasons for women’s lack of participation in the fields of math and science, but rather it is due to situational factors. Steps need to be taken in educational settings, such as revising teaching strategies, classroom makeup, teacher-student relationships, career guidance, and co-curricular activities (Funk, 2002). Interventions and steps to decrease the inequities between females and males are important because, when nothing is being done, female students will continue to be the voiceless student, as they are not getting anything positive in return for their academic potential and ability and are being ignored. While many of the factors and issues mentioned in research about gender inequity is aimed at older-aged females and their future, I feel that it is beneficial to concentrate on the youngeraged females and what can be done to prevent these inequities. It is important that girls have role models, and that programs are implemented in educational settings to convey to girls and women that they are capable of excelling in math and in science, and that gender stereotypes about their ability are incorrect. From the research, I firmly believe that we need to concentrate on implementing strategies and we certainly need to begin at an earlier agethe elementary school age. This is where my connection lies to this issue; I would like to observe if these inequities are occurring unintentionally and unconsciously in my classroom. Regardless of if they are or not, I would then like to research and implement strategies that can be done or introduced to ensure that female students are given equal opportunities and that the gender stereotypes are diminished. References Barba, R. & Cardinale, L. (1991). Are females invisible students? An investigation of teacher-student questioning interactions. School Science and Mathematics, 91, 306-310. Funk, C. (2002). Gender equity in educational institutions: Problems, practices, and strategies for change. 3-22. Marx, D.M., & Roman, J.S. (2002). Female role models: Protecting women’s math test performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1183-1193. Ricks, F. & Pyke, S. (1973). Teacher perceptions and attitudes which foster or maintain sex role differences. Interchange, 4, 26-33. Sadker, D. & M. (1994). Failing at fairness: How america’s schools cheat girls. NY: Simon & Schuster. Schmader, T., Johns, M., & Barquissau, M. (2004). The role of stereotype endorsement in women’s experience in the math domain. Sex Roles, 50, 835-850. Thorne, B. (1992). Girls and Boys together…but mostly apart: Gender arrangements in elementary schools. Education and Gender Equality. Proposed Plan: Female students in the elementary school grades need to build self-confidence and understand that they are just as intelligent and hold the same abilities as males in the areas of math and science. In the United States, female’s participation in the fields of math and science and also, their standardized scores in these areas are decreasing and are significantly lower than male’s. I believe that this is a result of gender stereotypes that send the message that only males can excel in math and science and the related fields. Also, this concept stems at an earlier stage, in the educational setting- where gender inequity is seen in many classrooms around the U.S. A conscientious effort is needed to help convey to girls and women that they are capable of excelling in math and in science, and that gender stereotypes about their ability are incorrect. This can be achieved through implementing programs and services, as well as making changes in the educational environment, and increasing teacher-female student interactions. - Will positive interactions with the female students (closer proximity, increased attention, encouragement, higher-level questions) result in a better self-concept? - Will these interactions result in a change of scores/performance on the science and math tests during that academic school year? What types of programs and services can be implemented in the school (co-curricular and extra-curricular) that could help in diminishing the female gender stereotype? -