UNIT 8: ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISESES

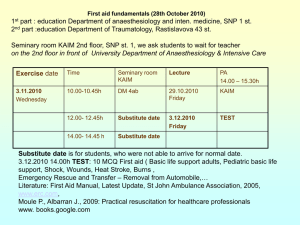

advertisement