Lower Urinary Tract Fistulas

advertisement

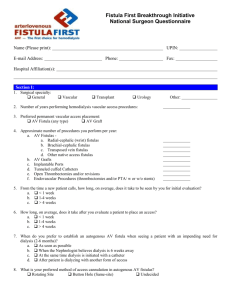

Lower Urinary Tract Fistulas Zhou Jianhong HISTORIC PERSPECTIVES The earliest evidence of a vesicovaginal fistula was reported by Derry (1935)in the mummified remains of Queen Henhenit,one of the of King Mentuhotep II of Egypt (11th Dynasty,circa 2050 b.c). In his dissection of the mummy at the Cairo School of Medicine in 1923,Derry noted a large vesicovaginal fistula in the presence of a severely contracted pelvis;he concluded that the presence of a severely contracted obstructed labor. Zacharin (1988) states that de Mercado first used the term fistula instead of the usual term rupture. The discovery of antibiotics and the development of general and regional anesthesia contributed significantly to the surgical treatment of vesicovaginal fistulas in the twentieth century. EPIDEMIOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY Wounded tissue undergoes four phases of healing:coagulation, inflammation, fibroplasia, and remodeling. Between the first and third weeks, healing is most vulnerable to hypoxia, ischemia, malnutrition, radiation, and chemotherapy, so this is the time when most fistulas present. 1 Obstetric Fistulas The vast majority of vesicovaginal fistulas that occur in developing countries are caused by obstetric trauma. Of 377 cases reported by Lawson (1989) from Ibadan, Nigeria, 369(97.9%) were obstetric and 343 were a consequence of obstructed labor. Obstructed labor remains the most important cause of vesicovaginal fistulas in developing countries. Absent or untrained birth attendants, reduced pelvic dimensions (caused by early childbearing, chronic disease, malnutrition, and rickets), uncorrected inefficient uterine action, malpresentations, hydrocephalus, and introital stenosis secondary to tribal circumcision all contribute to obstructed labor. Prolonged impaction of the presenting fetal part against a distended edmatous bladder eventually leads to pressure necrosis and fistula formation. Fistulas may be caused by trauma from forceps, instruments used to dismember and deliver stillborn infants, and surgical abortion. Vesicovaginal fistulas can follow cesarean delivery of peripatum hysterectomy (particularly in the presence of distorted anatomy, e.g, massive fibroids), hemorrhage, and surgical inexperience. Gynecologic Fistulas In developed countries, abdominal surgery, particularly total abdominal hysterectomy, is the major cause of genitourinary fistulas. Fistulas related to surgery performed by obstetrician-gynecologists 2 account for approximately 80% of all urogenital fistulas. The remaining 20% is divided among urologists and colorectal, vascular, and general surgeons. Predisposing risk factors for vesicovaginal fistula include a history of pelvic irradiation, cesarean section, endometriosis, previous pelvic surgery or pelvic inflammatory disease, diabetes mellitus, concurrent infection, vasculopathy, and tobacco use. The risk of ureteral injury was greater with laparoscopic procedures than with open procedures. PRESENTATION AND INVESTIGATION Patients with genitourinary fistulas present in many ways. Gross hematuria or abnormal intraperitoneal fluid accumulation (urinoma) noted during or after surgery should raise suspicion of an unrecognized urinary tract injury and dictates immediate investigation. Post-surgical fistulas usually present 7 to 21 days after surgery. Most patients have urinary incontinence or persistent vaginal discharge. Other signs and symptoms include unexplained fever; hematuria; recurrent cystitis or pyelonephritis; vaginal, suprapubic, of flank pain; and abnormal urinary stream. The initial evaluation of all patients with symptoms of genitourinary fistulas starts with a complete physical examination. A thorough speculum examination of the vagina may reveal the source of fluid, which 3 can then be collected; measurement of its urea concentration may identify it as urine. Urine should be examined microscopically and cultured, and appropriate treatment should be instituted for infection. Urethrovaginal fistulas are usually easily diagnosed on physical examination. Further office evaluation, cystourethroscopy, and intravenous urogram permit the physician to localize the fistula, determine adequacy of renal function, and exclude or identify other types of urinary tract injury. Office testing is often able to distinguish between fistulas involving the bladder or ureters. Instillation of methylene blue or sterile milk into the bladder stains vaginal swabs or tampons in the presence of a vesicovaginal swabs or tampons in the presence of a vesicovaginal fistula. Unstained, but wet, swabs may indicate a ureterovaginal fistula. Intravenous indigo carmine can be given and the tampon observed for blue staining. Use of intravenous methylene blue must be chosen with caution because of the risk of methemoglobinemia, a rare but serious complication. Radiologic imaging is recommended in most cases and usually includes intravenous urography or cystoscopic retrograde urography. Renal ultrasound may miss up to 20% of ureteral injuries. A Tratner catheter may be useful in cases of suspected urethrovaginal fistula. Cystourethroscopy is indicated in most cases. The size, site, and number of fistulas and condition of local tissues are carefully noted. Key 4 observations include the fistula’s proximity to the bladder neck, urethral sphincter, and ureteral orifices as well as the presence of tissue edema, slough, infection, induration, scarring, and fixity to bone. CONSERVATIVE MANAGEMENT Various conservative or minimally invasive therapies are available for vesicovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulas. However, the true viability and success of these treatment modalities remain to be determined. Various conservative or minimally invasive therapies are available for vesicovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulas. Previously, it bas been empirically stated that fistulas diagnosed within 7 days of occurrence, that are less than 1 cm in diameter and unrelated to malignancy or radiation, may spontaneously resolve with up to 4 weeks of continuous drainage in anywhere from 12% to 80% of cases. Once the diagnosis of a ureterovaginal fistula is confirmed, recommended initial management is ureteral stenting (de Baere et al, 1995; Selzman et al., 1995). Stenting is more successful when performed sooner rather than later. If a stent is placed successfully, it should be left in for 6 to 8 weeks. If the fistula has not healed at 6 weeks, a repeat examination may be performed at 8 weeks, with preparation to proceed with preparation to proceed with surgical repair, if the fistula has still not healed. 5 TIMING OF SURGICAL REPAIR Ideally, early repair of vesicovaginal fistulas requires diagnosis of the fistula within 72 hours of the injury. During this period, the tissues are often supple and normal in appearance and can be dissected and closed without tension. Early repair can be performed either transvaginally or transabdominally. Fistulas identified, at this time, are complicated by infection and induration, making closure difficult. Once these changes have occurred, a 3-to 6-month waiting period bas been recommended, allowing for maturity of the fistula. During this waiting period, vaginal examination should be performed every 3 to 4 weeks to monitor the inflammation and infection. PRESURGICAL MANAGEMENT Once the decision has been made to proceed with surgical correction of the fistula, patients waiting surgical repair need considerable psychological support. Leakage from small fistulas may be controlled by frequent voiding and the use of tampons, perineal pads, or silica-impregnated incontinence pants. A vaginal diaphragm with a watertight attachment to a urinary catheter can collect urine from larger fistulas in a leg bag. Perineal care is important and makes the patient more comfortable and tolerant of delayed closure. Before surgical repair, 6 vaginal or oral estrogen should be given to women who are surgically or naturally postmenopausal to improve urogenital tissue integrity. In malnourished patients a high-protein diet, Vitamin, and trace elements supplements, and correction of anemia are essential before surgical repair, Surgery should not be performed during menstruation because of the increased tissue vascularity at that time. SURGICAL REPAIR Vaginal Repair of Vesicovaginal Fistula 7