No 13: Paecilomyces - Johns Hopkins Medicine

advertisement

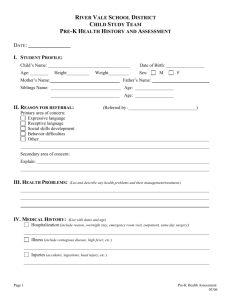

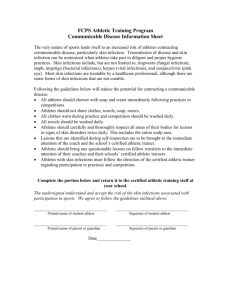

THE JOHNS HOPKINS MICROBIOLOGY NEWSLETTER Vol. 26, No. 13 Tuesday, August 14, 2007 A. Provided by Emily Luckman, Division of Outbreak Investigation, Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. There is no information available at this time. B. The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Department of Pathology, Information provided by, Terina Chen, M.D. Case presentation: A 13 year-old female with cystic fibrosis presented to the outpatient clinic for routine follow-up. Several months earlier, a sputum culture was positive for Pseudomonas. She reported no significant cough, wheezing or sputum production and was free of abdominal complaints. Her activity level and dietary intake were both excellent. Maintenance medications included Ultrase, Advair, cromolyn, Pantoprazole and a multivitamin. Her physical exam was unremarkable. Nevertheless, pulmonary function testing continued along the declining trend which had been observed over the past 6 months. She was admitted for bronchoscopy which revealed diffuse inflammation and tracheal bronchitis associated with moderate purulent secretions. She was discharged to complete a 2 week course of intravenous tobramycin and ticarcillin. The BAL specimen grew light Paecilomyces lilacinus in two of four tubes/plates at seven days as well as mixed respiratory flora. Epidemiology: Paecilomyces species, while still a rare cause of human disease, appear to be emerging fungal pathogens. This environmental mold has been recovered throughout the world from soil, vegetation and air, and has in the past contaminated products such as skin lotions. It is well-recognized that Paecilomyces may cause serious infections in immunocopromised patients, though interestingly the incidence seems to be increasing in the immunocompetent. P. lilacinus and P. variotii are the species most often associated with human disease. Its significance in patients with cystic fibrosis is not well documented, though in all likelihood it represents a colonizing organism. Clinical aspects: Injury to the skin or mucosal barriers represents a major factor in the ability of Paecilomyces to cause disease. Specifically with regards to P. lilacinus, ocular infections and cutaneous/subcutaneous infections comprise the vast majority of cases, though involvement of multiple other sites has been reported. In contrast to other Paecilomyces, P. lilacinus typically shows a poor response to standard antifungal drugs. In all instances, removal of foreign bodies at the site of infection is advised. Ocular infections: P. lilacinus has an affinity for ocular structures, particularly when they are altered by lens implantation, trauma or surgery. Contact lenses are a more minor predisposing factor. Serious complications such as vision loss and enucleation are alarmingly frequent. As yet, the optimal therapy for ocular infections caused by P. lilacinus has not been established. A combination of locally-administered and systemic antifungals, in addition to surgery, may be required. Cutaneous & subcutaneous infections: Immunocompromised states, such as solid organ and bone marrow transplantation, underlying malignancy and corticosteroid use, are the most significant risk factor for cutaneous and subcutaneous P. lilacinus infections. Clinical features of skin involvement are not reproducible in that the lesions may be solitary or disseminated and display highly variable morphologies. Both cutaneous and subcutaneous infections tend to appear insidiously. Specific treatment regimens are again not defined, but surgical debridement seems to improve outcome for deep or extensive lesions. Treatment failure is not infrequent in the literature, regardless of the intervention. Non-ocular, non-cutaneous infections: P. lilacinus is capable of infecting multiple other sites, as illustrated by a variety of case reports. Sinus, nail bed, vaginal, lung, pleural, bone and blood infections have all been described. Among these, sinusitis and indwelling catheter-related fungemia have been most common. Non-cutaneous, non-ocular infections caused by P. lilacinus appear to more favorably respond to antifungal and/or surgical treatment. Laboratory identification & antifungal susceptibilities: Routine fungal media is adequate to grow P. lilacinus in culture. Depending on the specific media used, the fungal colonies may display a distinctive light violet or wine color which aids in its identification. Microscopically, this organism features chains of multiple elliptical conidia extending from the tips of long tapered phialides. P. lilacinus can sporulate in infected tissue; biopsy material may reveal fungal forms suggestive of Paecilomyces on histologic sections, though culture is required for definitive diagnosis. Specific identification of P. lilacinus is important because of its resistance to often employed antifungal drugs. While relatively little data is available, most studies have shown poor in vitro and clinical response to amphotericin B. Fluconazole and flucytosine have almost no in vitro activity against P. lilacinus, and likewise, clinical results have been suboptimal. Ketoconazole and other older azoles have yielded conflicting reports. Posaconazole, ravuconazole and in some studies, voriconazole, have shown the lowest minimum inhibitory concentrations thus far. Combination therapy has shown promise in in vitro studies. Further clinical and laboratory studies are needed to more clearly define optimal therapy for P. lilacinus infections. References: 1. Orth B et al. “Outbreak of invasive mycoses caused by Paecilomyces lilacinus from a contaminated skin lotion.” Ann Intern Med 1996; 125(10):799-806. 2. Pastor FJ et al. “Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcomes of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections.” Clin Microbiol Infect 2006; 12:948-60. 3. Winn W et al. Koneman’s Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology, 6th edition. 2006. p. 1182. 4. van Schooneveld T et al. “Paecilomyces lilcainus infection in a liver transplant patient: case report and review of the literature.” Transpl Infect Dis 2007 Jul 1 [Epub].