incidence, etiology, and management

advertisement

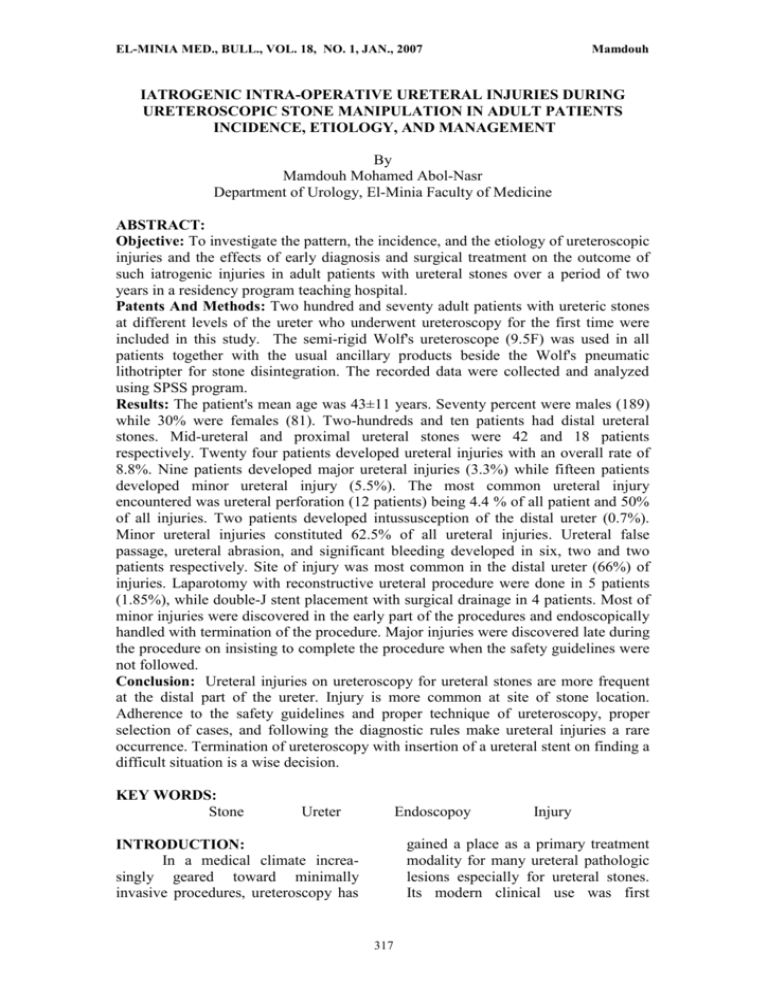

EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 18, NO. 1, JAN., 2007 Mamdouh IATROGENIC INTRA-OPERATIVE URETERAL INJURIES DURING URETEROSCOPIC STONE MANIPULATION IN ADULT PATIENTS INCIDENCE, ETIOLOGY, AND MANAGEMENT By Mamdouh Mohamed Abol-Nasr Department of Urology, El-Minia Faculty of Medicine ABSTRACT: Objective: To investigate the pattern, the incidence, and the etiology of ureteroscopic injuries and the effects of early diagnosis and surgical treatment on the outcome of such iatrogenic injuries in adult patients with ureteral stones over a period of two years in a residency program teaching hospital. Patents And Methods: Two hundred and seventy adult patients with ureteric stones at different levels of the ureter who underwent ureteroscopy for the first time were included in this study. The semi-rigid Wolf's ureteroscope (9.5F) was used in all patients together with the usual ancillary products beside the Wolf's pneumatic lithotripter for stone disintegration. The recorded data were collected and analyzed using SPSS program. Results: The patient's mean age was 43±11 years. Seventy percent were males (189) while 30% were females (81). Two-hundreds and ten patients had distal ureteral stones. Mid-ureteral and proximal ureteral stones were 42 and 18 patients respectively. Twenty four patients developed ureteral injuries with an overall rate of 8.8%. Nine patients developed major ureteral injuries (3.3%) while fifteen patients developed minor ureteral injury (5.5%). The most common ureteral injury encountered was ureteral perforation (12 patients) being 4.4 % of all patient and 50% of all injuries. Two patients developed intussusception of the distal ureter (0.7%). Minor ureteral injuries constituted 62.5% of all ureteral injuries. Ureteral false passage, ureteral abrasion, and significant bleeding developed in six, two and two patients respectively. Site of injury was most common in the distal ureter (66%) of injuries. Laparotomy with reconstructive ureteral procedure were done in 5 patients (1.85%), while double-J stent placement with surgical drainage in 4 patients. Most of minor injuries were discovered in the early part of the procedures and endoscopically handled with termination of the procedure. Major injuries were discovered late during the procedure on insisting to complete the procedure when the safety guidelines were not followed. Conclusion: Ureteral injuries on ureteroscopy for ureteral stones are more frequent at the distal part of the ureter. Injury is more common at site of stone location. Adherence to the safety guidelines and proper technique of ureteroscopy, proper selection of cases, and following the diagnostic rules make ureteral injuries a rare occurrence. Termination of ureteroscopy with insertion of a ureteral stent on finding a difficult situation is a wise decision. KEY WORDS: Stone Ureter Endoscopoy Injury gained a place as a primary treatment modality for many ureteral pathologic lesions especially for ureteral stones. Its modern clinical use was first INTRODUCTION: In a medical climate increasingly geared toward minimally invasive procedures, ureteroscopy has 317 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 18, NO. 1, JAN., 2007 described in the late 1970s by Lyon et al., as were the first complications1, 2. Several large series have been published on rates and types of complications with an overall complication rates have ranged from 8% to 16%3-7. With the increased surgical experience and improvements in endoscopic equipment, the overall intraoperative complication rates of uteroscopy have decreased greatly. Mamdouh All patients were adult age who had single or multiple ureteral stones. Patients with severe hydronephrosis, those who had associated urinary tract infections, and those who had large ureteral stones were all excluded from this study. Twelve patients who had their procedure aborted because of inaccessibility to the ureteral meatus were also excluded .Three of them due to failure of guidewire insertion, seven due to technical difficulty during procedure, and lastly two who developed bladder neck injury at beginning of the procedure. Six patients who had proximal stone migration into a renal calyx at the beginning of the procedure with a double-J stent insertion were also excluded from this study. Ureteral injuries are classified based on their severity into minor and major injuries. Minor complications make up the majority of incidents encountered during ureteroscopy. These can be effectively managed by non-operative means with minimal sequelae. Major complications constitute injuries that necessitate operative intervention or that are life-threatening. In two large series, open surgery was performed in only 0.22% of patients3,10. Although these injuries are clearly rare, they can have enduring effects that contribute to long-term morbidity. Pre-operative work-up included urine analysis and culture, complete blood picture, and biochemical study in addition to plain film of the urinary tract and intravenous urography. Preoperative Plain film of the urinary tracts was done before the procedure. Pre-operative one gram cefotaxime was given intra-venously on call to operative theatre. This study aimed to investigate the pattern, the incidence, and the etiology of the complications that occur during uretral stone manipulation in adult patients using the semi-rigid ureteroscope and pneumatic lithotripsy. The study was done in a teaching hospital with a residencyprogram over a period of two years duration. The semi-rigid Wolf's ureteroscope (9.5F) was used in all patients together with the usual ancillary products beside the Wolf's pneumatic lithotripter for stone disintegration. Ureter-vesical complex dilation was done in 193 procedures (71.5%) while direct introduction of ureteroscope was performed without preliminary dilation in 77 procedures (28.5%). All procedures had been planned to have in-situ disintegration of the stone and extraction of large stone fragments using dormia basket. At the end of the procedure a double-J stent was inserted and left for 4-8 weeks to PATIENTS AND METHODS: Retrospective study and review of 270 files of adult patients who underwent ureteroscopic manipulation for their ureteral stones was done over a period of two years in King Fahad Hospital Hofuf, Saudi Arabia from October, 2005 to December 2007. 318 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 18, NO. 1, JAN., 2007 ensure ureteral patency and avoid complications in the post-operative period. Mamdouh 189 (70%) males and 81 (30%) females. The location of the ureteral stone was as follows: 210 (77.7%) case had the stone in distal ureter, 42 (15.6%) case had their stone in midureter, while 18 (6.7%) of the patients had their stone in the proximal ureter respectively. The ureteral stones size ranged from 0.9 mm to 1.6 mm. While 151 of the stones were present in the left ureter (55.9%), 119 of the patients had their stones on the right side (44.1%). Patients' demographics and ureteral stone criteria are shown in table (1). All recorded data related to patient age, sex, previous surgery and stone site, size and density in addition to procedures time and any difficulties and details of complications were collected and analyzed using SPSS program. RESULTS: The patient age ranged from 19 to 61 years with a mean age of 43±11 years. Patients' sex distribution was Table (1): Patients' demographics and ureteral stone criteria Item - Total number: - Mean age: - Sex distribution: - Site of the stone: - Proximal ureter: - Mid-ureter: - Distal ureter: - Side of the stone Number (270) patients 43 ± 11 years (range:19 - 61 years) 189 males / 81 females (210) patients (42) patients (18) patients (151) left ureter – (119) right ureter Out of all the 270 ureteroscopic procedure, twenty four patients developed intra-operative ureteral injury with an overall ureteral injury rate of 8.88%. Nine patients developed major ureteral injuries (3.3%) while fifteen patients developed minor ureteral injury (5.5%). The most common ureteral injury encountered was ureteral perforation; major and minor (12 patients) being 4.44 % of all patient and 50% of all injuries. The second most common but being a minor injury was false passage of the distal ureter in four cases and in the midureter in two which were made during insertion of the guide wire in all cases. Percentage (100 %) 70% / 30% 77.7 % 15.6 % 6.7 % 55.9% - 44.1% The incomplete avulsion with extensive extravasation occurred in seven cases (2.59%). All patients necessitated surgical intervention. Two patients underwent uretero-vesical reimplantation, one female patient underwent resection and reanastomosis of the proximal right ureter, while four of them had just double-J stenting during open surgical drainage of the extravasated contents. Perforation was insignificant with mild extravasation in five patients (1.85%) who underwent double-J stent insertion just diagnosed by retrograde fluoroscopic study. 319 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 18, NO. 1, JAN., 2007 Two male patients developed ureteral intussusception of the distal ureter (0.74%). The two patients underwent ureterovesical reimplantation. The first patient was an adult male patient whose ureteral lumen was narrow and the ureteroscope was inserted directly without dilatation and the injury followed on forceful dragging of the ureteroscope. The second patient was 62-years old male patient who underwent ureteroscopy also without dilatation. He developed a ureteral tumor bulging into the bladder after ureteroneocystostomy. Mamdouh common minor injuries constituting 25% and about 21% of all injuries in our study. Ureteral abrasion occurred in two patients and significant bleeding developed in also two patients. The source of bleeding could not be identified. False passage constituted 25% of all injuries in our series (2.2%) more commonly in the distal part of the ureter and 80% of them occurred at site of stone location. All false passages in our study were attributed to forceful placement of the ureteroscopewithout dilatation in two cases and by guidewire itself in three cases. In all the cases of false passages development, the injury occurred during the early steps of the procedure by means of retrograde imaging. A double-J stent was inserted with termination of the procedure in all these patients. Two patients developed bleeding, one before and one after stone removal. A double-J stent was inserted in these two patients and both were given blood transfusion and bleeding stopped with conservative treatment. The overall major ureteral injuries constituted about 37% of all injuries. Despite ureteral reconstruction and normal urographic features, the five patients still have intermittent loin pain. Major ureteral injuries with its incidence and outcome are shown in table (2). Minor ureteral injuries constituted 62.5% of all ureteral injuries in our study. This constitutes 5.55% of all patient involved in this study. Ureteral false passage and perforation with mild extravasation were the most Table (2): Types, incidence, and outcome of ureteral injuries Type of injury Total No. % injury % of patients - Major injuries: 9 3.33% - Partial avulsion: 7 29.1% 2.60% - Intussusception: 2 8.3% 0.74% - Minor injury: 15 5.55% - False passage: 6 25.0% 2.22% - Ureteral abrasion: 2 8.3% 0.74% - Perforation: 5 20.8% 1.85% - Significant bleeding: 2 8.3% 0.74% Management Surgery D-J stenting (3) repair (4) + Drainage (2) repair -- - Total (5) 24 100% Five patients developed minor perforation with mild extravasation (1.85%). They were treated by doubleJ stent insertion with termination of the procedure in two cases. The other 8.88% ----- (6) + 6 Termination (2) (5) + 2 Termination (2) + 1 Termination (19) three patients were found to have extravasation on doing retrograde ascending uretero-pyelogam at the end of the procedure. A double-J stent was inserted and all of the patients had no 320 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 18, NO. 1, JAN., 2007 post-operative complications. Minor ureteral injuries and their outcome are shown in table (2). Mamdouh the distal part of the ureter, and two developed perforation with mild extravasation. The injury occurred at any level of the ureter but the distal part of the ureter has the most predilections being injured in two thirds of all injuries. The proximal and the middle part of the ureter were involved in one third of the injuries and were equally affected. The sex distribution and the anatomical location of ureteral injuries, both are demonstrated in table (3). Eighteen out of the twenty-four ureteral injuries (75%) occurred in male patients while only six female patients (25%) were involved. Eighteen out of 189 males developed ureteral injuries (9.5%) while six out of 81 females had ureteral injury (7.4%). Two female patients developed partial avulsion of the ureter, two developed ureteral false passage in Table (3): Sex distribution and anatomical location of ureteral injury Type of injury - Major injuries: - Partial avulsion - Intussusception: - Minor injury: - False passage: - Ureteral abrasion: - Perforation: - Significant bleeding: - Uretal injuries: - Total patients: Number 9 7 2 15 6 2 5 2 24 270 Sex Distribution Males Females* 5 2 2 -4 2 3 2 18 189 As regard the location of the stone and its effect on ureteral injury, we found that most of the major ureteral injuries occurred at the site or location of the stone (seven out of nine patients). Seventy-nine percent of all ureteral trauma occurred at the level of stone location. The source of bleeding was not identified whether from 2 -2 -6 81 Site of the injury Proximal Middle Distal 2* 1 4* --2 (*) means a female patient. -2 4** 1 -1 1* 1 3* --2 4** 4 16**** Male rate: 9.5% Female rate: 7.4% middle or distal ureter. False passage of the ureter occurred in the distal part of the ureter in most of the cases. This type of ureteral minor injury definitely occurred distal to the stone location. The overall safe non-injurious ureteroscopic procedure was 91.2%. The relation between the stone location and the site of injury is shown in table (4). 321 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 18, NO. 1, JAN., 2007 Mamdouh Table (4): Stone location and the site of ureteral njury Type of injury - Major injuries: - Partial avulsion - Intussusception: - Minor injury: - False passage: - Ureteral abrasion: - Perforation: - significant bleeding: - Uretal injuries: - Total No. patients: NO. 9 7 2 15 6 2 5 2 24 270 Stone site of affected Pt. Proximal Mid Distal 4 1 2 2 1 1 2 8 18 1 1 3 42 As regard the etiological factors that lead to or predispose to the ureteral injury, the neglect of insertion of the safety guide-wire and forceful aggressive insertion of the ureteroscope were the most common causes of ureteral injuries that occurred in eleven times and ten times respecttively. Inadvertent clumsy ureteroscopy was responsible for most of the major ureteral injuries (all cases of extensive perforation and distal ureteral intusssception in addition to the two cases of significant bleeding) especially if either inserted without a guide-wire (4), on a guide wire in a false passage (1), or without dilatation of the uretero-vesical complex (2). The etiology of injury and the time of its diagnosis are shown in table (5). Site of the injury Proximal Middle Distal 2 ++ 1+ 4 ++ 2 ++ (+) means injury at site of the stone 5 2 4 +++ 1 1+ 1+ 2 1+ 1+ 3 ++ 1 2?? 13 4 4 16 210 Safe complete procedure: 246 (91.2%) Personnel who were insisting to complete the procedure by any means or tracing the migrating stones in the upper ureter were involved in performing the major injuries. Dilatation of the ureter-vesical junc-tion was not done in seven of the cases while performing ascending retrograde imaging on time was not appreciated seven cases also. Placement or replacement of the safety guide wire during work was not appreciated in eleven cases and this event was involved in most major injuries. The dormia stone basket was the causative factor in only two cases. Injuries that were discovered at early time of the procedure and endoscopically handled with insertion of a ureteral stent had an eventful postoperative course. The hospital stay was two days. The patients who developed major ureteral injuries had a mean hospital stay of eleven days and the operative time was prolonged at least two hours more than patients who underwent early ureteral stenting. Surprisingly, seven of the nine major ureteral injuries were done by consultant well-experienced with ureteroscopy. On the other hand, all the minor injuries beside one case of the significant bleeding were done resident urologists under training. 322 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 18, NO. 1, JAN., 2007 Mamdouh Table (5): Etiology and time at diagnosis of the ureteral injury Injury Type DILAT - Partial avulsion: ++ - Intussusception: ++ - False passage: ** - Ureteral abrasion: - Extravasation: ++ - Significant bleeding: + SGW ++++ ++ +++ - Total 11/24 9/24 Etiology RPG +++++ ++ -- ++ 7/24 URS +++ ++ -+ ++ ++ 10/24 DORMIA ---+ + 2/24 Time at diagnosis EARLY LATE 2 5 2 5 1 2 4 1 2 13/24 were made by means of the ureteroscope and mostly at the site of the stone. The first report of avulsion was reported in 1967 by Hart16. Luckily, its occurrence is relatively rare with rates of 0% to 0.5% reported in several large series3,8,10,18). This high rate in our study was attributed to prolonged procedure for upper ureteral stones or inserting the semi-rigid ureteroscope into the ureter without preliminary dilatation depending on experience. Both the indications and the guidelines of a safe procedure were not properly followed. Avulsion generally occurs during forceful removal of a stone through a segment of ureter with a diameter smaller than the stone itself. In our study, two cases occurred in the proximal ureter at site of stone location but the distal ureter was the most commonly affected. The proximal third of the ureter is at particular risk as it has less muscle support and contains a thinner layer of mucosal cells than the distal ureter (17). Additional risks for avulsion include the presence of an impacted stone, stone retrieval in a diseased portion of the ureter, and the use of multiple wire baskets19. DISSCUSSION: Any operative procedure either surgical or endoscopic definitely has a complication rate. As the ureter is a slender tubal structure, ureteral injuries do occur especially during ureteroscopic stone manipulation. The ureteral injury in our study was estimated in a special environment in a teaching hospital for special patients who have ureteric stones along the whole ureter. The intra-operative ureteral injury rate was 8.9% in our study. The most serious and frustrating injury was ureteral intussusception; 0.74% of all patients. A small number of iatrogenic causes have been described including retrograde intussusception as a result of repeated ureteroscopy14. With the use of larger ureteroscopes earlier, there were also instances of the ureter being dragged proximally as the ureteroscope was advanced15. This happened in our two cases where the large ureteroscope was inserted without dilatation of the intramural ureter into a small ureter in one case and a harder ureterin the other case who developed tumor later. Intussusception should be suspected when there is difficulty placing a stent at the end of the procedure 14. The early recognition of our cases leaded to the high rate of surgical repair and drainage of the associated extravasaion with stenting of the ureter. All our patients do well Partial ureteral avulsion occurred in 2.6% in our study and all 323 11/24 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 18, NO. 1, JAN., 2007 Mamdouh on long term follow-up. If the stone does not travel easily with the basket then basketing should be abandoned and either lithotripsy should be performed or stenting must be considered if significant trauma is present. Vigilance should be employed with proximal stones15. Open repair is the mainstay of treatment of ureteral avulsion that is dependent on factors such as location of the avulsion and length of devitalized ureterand patient age and comorbidities, and renal function15. Proximal and middle ureteral short avulsions can be treated with ureteroureterostomy. Distal injuries are best addressed with ureteroneocystostomy. However, longer ureteral defects as well as those in the middle third may require the addition of a psoas hitch, a Boari flap, or a combination of both18 rate of perforation was attributed to that our study involved only ureteral stones which are most difficult to manipulate. All instruments in the ureteroscopic armamentarium have the potential to perforate the ureter. The vast majority of perfo-rations is small and can be managed conservatively with ureteral stent placement for 4-6 weeks15. Ureteral perforation occurred in 1.85% of our cases followed by mild extravasataion and all developed at the site of stone location. Both the early diagnosis and ureteral stenting made an excellent outcome. Although the reported incidence of ureteral perforation has decreased over the last several decades, it remains one of the most common complications15. Excessive force and improper placement of the ureteroscope, in particular when entering the ureteral orifice, can easily result in a false passage necessitating termination of the procedure15. Guidewires, stone retrieval baskets, and lasers are all capable of creating false passages especially in the treatment of urolithiasis15. If a false passage is not appreciated, a truly disastrous conesquence can occur if the ureteroscope is then passed over the misplaced guidewire21. The ensuing dissection can interfere with ureteral blood supply resulting in necrosis and stricture even loss of the entire ureter. These injuries are benign and treatment generally consists of ureteral stenting for 2-4 weeks15. False passage constituted 25% of all injuries in our series (2.2%) more commonly in the distal part of the ureter. Often, false passages are overlooked and many series fail to comment or report on them5,6,10. In a series of iatrogenic ureteric injuries, Al-Awadi et al., described 15 false passages (18.3%), making it one of the most common complications in their series20. The first perforations were reported by Lyon et al., in the late 1970s1, 2. Early series had perforation rates exceeding 15%. In 1987, Kramolowsky reported perforations in 17% of 142 ureteroscopic proce-dures19. Development of smaller diameter ureteroscopes had a dramatic impact on reported perforation rates. In 1993, Abdel-Razzak and Bagley had only one minor perforation out of 65 cases on using the semirigid ureteroscope (6.9F)9. Recent large series reporting on complications cite perforation rates between 0.5% and 4.7% with the majority at 1% or less 3–6,10. Our high Like most complications, adherence to proper technique and safety will make this a rare occurrence. Passing the ureteroscope over a guidewire can help navigate difficult passageways while balloon dilatation 324 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 18, NO. 1, JAN., 2007 can make narrow ureters easier to traverse. If a guidewire cannot easily pass a point of obstruction, an angledtip hydromer-coated guidewire should be utilized to bypass the area gently. A safety wire is imperative as cases where the ureter is impassable will require a stent22. Mamdouh In our study, 0.7% developed bleeding that required transfusion. Geavlete et al., reported a rate of 0.1%, where visibility difficulties secondary to bleeding forced them to halt the procedure and place a ureteral stent3. In their series of 290 cases, AbdelRazzak and Bagley reported on three patients that had prolonged bleeding lasting longer than two days24. None of these patients required blood transfusion. Small perforations with mild extravasation occurred in 1.85% of our cases. In their series of 290 procedures, Abdel-Razzak and Bagley described three cases of extravasation (1.0%) (25=29). Our high rate is attributed to that we included only patients with stones in our study and our larger ureteroscope (9.5F) compared to that used in Bagley' study (6.9F). In general, small perforations result in minor amounts of extravasation that are of no clinical significance. When the safety guidelines of a proper ureteroscopy were not taken into consideration, complications and definitely the injury rate will be increased. The neglect of insertion of the safety guidewire and forceful aggressive insertion of the ureteroscope were the most common causes of major ureteral injuries inour study. Refusal of doing dilatation of the intramural ureter and the neglect of performing ascending retrograde imaging on time were the second most common etiological factors. Personnel who were insisting to complete the procedure by any means or tracing the migrating stones in the upper ureter were involved in performing the major injuries. Mucosal abrasion occurred in less than 1% in our study. Any instrument passed through the ureter can cause mucosal abrasions. The larger the instrument, the more is the friction applied to the ureteral mucosa (15) . Identifiable mucosal abrasions were reported in 0.3% of 2273 patients by Butler et al.,10. They noted that the seven mucosal tears were caused by the ureteroscope itself but in our study it occurred one by means of dormia basket in one case having a lower ureteral stone and the other by the ureteroscope itself at the proximal ureter at site of stone location. Geavlete et al., likewise reported a low incidence in their series with mucosal abrasions being found in 1.5% of patients3. These lesions generally have no significant consequence. In most cases, only observation is warranted. If there is considerable bleeding or edema, obstruction may ensue and a ureteral stent should be placed for drainage23. CONCLUSION: Ureteral injuries on ureteroscopy for ureteral stones are more frequent at the distal part of the ureter. Injury is more common at site of stone location. Adherence to the safety guidelines and proper technique of ureteroscopy, proper selection of cases, and following the diagnostic rules make ureteral injuries a rare occurrence. Termination of ureteroscopy with insertion of a ureteral stent on finding a difficult situation is a wise decision. REFERENCES: 325 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 18, NO. 1, JAN., 2007 1. Lyon ES, Kyker JS, Schoenberg HW. Transurethral ureteroscopy in women: a ready addition to the urological armamentarium. J Urol 1978; 119:35–36. 2. Lyon ES, Banno JJ, Schoenberg HW. Transurethral ureteroscopy in men using juvenile cystoscopy equipment. J Urol 1979; 122:152–153. 3. Geavlete P, Georgescu D, Nita G, et al., Complications of 2735 retrograde semirigid ureteroscopy procedures: a single-center experience. J Endourol 2006; 20:179–185. 4. Harmon WJ, Sershon PD, Blute ML, et al., Ureteroscopy: current practice and long-term complications. J Urol 1997; 157:28–32. 5. Schuster TG, Hollenbeck BK, Faerber GJ, Wolf JS Jr. Complications of ureteroscopy: analysis of predictive factors. J Urol 2001; 166:538–540. 6. Chow GK, Patterson DE, Blute ML, et al., Ureteroscopy: effect of technology and technique on clinical practice. J Urol 2003; 170:99–102. 7. Francesca F, Scattoni V, Nava L, et al., Failures and complications of transurethral ureteroscopy in 297 cases: conventional rigid instruments vs. small caliber semirigid ureteroscopes. Eur Urol 1995; 28:112–115. 8. Weinberg JJ, Ansong K, Smith AD. Complications of ureteroscopy in relation to experience: report of survey and author experience. J Urol 1987; 137:384–385. 9. Abdel-Razzak O, Bagley DH. The 6.9 F semirigid ureteroscope in clinical use. 1993; 41:45–48. 10. Butler MR, Power RE, Thornhill JA, et al., An audit of 2273 ureteroscopies—a focus on intra-operative complications to justify proactive management of ureteric calculi. Surg J R Coll Surg Edinb Irel 2004; 2:42–46. 11. Moretti KL, Jose JS. Ureteral intussusception owing to a malignant Mamdouh ureteral polyp. J Urol 1987; 137:493– 494. 12. Gabriel JB Jr, Thomas L, Guarin U, et al., Ureteral intussusception by papillary transitional cell carcinoma. Urology 1986;28:310–312. 13. Duchek M, Hallmans G, Hietala SO, et al., Inverted papilloma with intussusception of the ureter. Case report. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1987; 21:147–149. 14. Bernhard PH, Reddy PK. Retrograde ureteral intussusception: a rare complication. J Endourol 1996; 10:349–351. 15. Yanke, B. and Bagley, D.: complications in ureteroscopy: In complications of urologic surgery and practice: Loughlin, Kevin R.: 2007; Chapter 32:443-454. 16. Hart JB. Avulsion of the distal ureter with Dormia basket. J Urol 1967; 97:62–63. 17. de la Rosette J, Skrekas T, Segura JW. Handling and prevention of complications in stone basketing. Eur Urol 2006; 50:991–999. 18. Alapont JM, Broseta E, Oliver F, et al., Ureteral avulsion as a complication of ureteroscopy. Int Braz J Urol 2003; 29:18–23. 19. Kramolowsky EV. Ureteral perforation during ureterorenoscopy: treatment and management. J Urol 1987; 138:36–38. 20. Al-Awadi K, Kehinde EO, AlHunayan A, Al-Khayat. Iatrogenic ureteric injuries: incidence, aetiological factors and the effect of early management on subsequent outcome. Int Urol Nephrol 2005; 37:235–241. 21. Lytton B, Weiss RM, Green DF. Complications of ureteral endoscopy. J Urol 1987; 137:649–653. 22. Chen GL, Bagley DH. Ureteroscopic surgery for upper tract transitional-cell carcinoma: complications and management. J Endourol 2001; 15:399–404. 326 Mamdouh EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 18, NO. 1, JAN., 2007 23. Johnson DB, Pearle MS, Complications of ureteroscopy. Urol Clin North Am 2004; 31:157-171. 24. Abdel-Razzak OM, Bagley DH. Clinical experience with flexible ;ureteropyeloscopy. J Urol 1992 148:1788–1792. إصابات الحالب أثناء إستخراج حصوات الحالب بإستخدام المنظـــار ممدوح محمد أبوالنصر قسم المسالك البولية – كلية طب المنيا أحدث إستخدام منظار الحالب ثورة عظيمة فى مجال جراحات مناظير المسالك البولية وخاصةً عمليات إستخراج وتفتيت حصوات الحالب .وحيث أنه يستحيل وجود عملية جراحية بال مضاعفات فإن لمنظار الحالب بالتأكيد نسبة مضاعفات له ،منها إصابات الحالب المختلفة والتى تم رصدها فى دراسات سابقة شملت كل أمراض الحالب. وقد إستهدفت هذه الدراسة بالتفصيل إصابات الحالب المختلفة أثناء عملية إستخراج حصوات الحالب فى الكبار ،وتم تقسيم هذه اإلصابات إلى إصابات كبرى والتى تطلبت الشق الجراحى للتعامل معها وإلى إصابات صغرى والتى قد تم التعامل معها من خالل المنظار بوضع دعامة حالبية عكازية الطرفين بالحالب .وقد أُجريت هذه الدراسة على مائتين وسبعين مريضا ً لديهم حصوات بالحالب فى أجزاءه المختلفة. وقد عانى أربعة وعشرون مريضا ً من إصابات مختلفة بالحالب بنسبة تسعــة بالمائة تقريباً .ومثـلت إصابات الحالب الكبرى نسبة ثمان وثالثين ونصف بالمائة منها .وقد تم تشخيص هذه اإلصابات فى وقت متأخر أثناء العمليةز وقد كان أخطر هذه المضاعفات هى تهتك الحالب بينما كان أكثرها شيوعا ً هي إحداث ثقب فى الحالب بدرجا ٍ ت مختلفة بنسبة خمسين بالمائة من كل حاالت اإلصابات (عدد إثنى عشرة مريضا) .وقد كان مكان إصابة الحالب أكثر حدوثا ً فى الجزء األسفل منه فى ثلثى الحاالت .وقد حدثت اإلصابات بالحالب نتيجة لعدم إتباع أقرتها جمعية المسالك البولية األمريكيةأناء إجراء إجراءات السالمة والخطوات اآلمنة والتى ّ عملية منظار الحالب منها إستخدام ووضع السلك المرشد أثناء العملية وإستخدام اآلشعة الصاعدة في الوقت المناسب والتعامل بمنتهى اللطف بالمنظار أثناء وجوده بالحالب. وقد خلصت هذه الدراسة إلى ضرورة إتباع إحتياطات و إجراءات السالمة والخطوات اآلمنة أثناء العملية لتفادى حدوث إصابات الحالب المختلفة ،كما أنه من الحكمــة بمكان وضـع دعامة حالبية عكازية الطرفين فى حال حدوث إضطراب أو حدوث مشاكل تقنية وإنهاء عملية منظار الحالب وتأجيل التعامل مع الحصوات لمرحلة الحقة. 327