Study of incidence of supracondylar process of humerus in the

advertisement

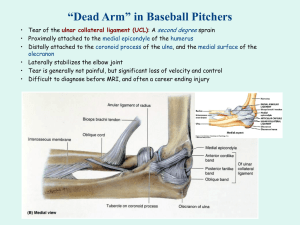

Study of incidence of supracondylar process of humerus in the population of Assam Abstract Background: Supracondylar process, in human, is a rare, anomalous, beak-like bony process on the anteromedial surface of the humerus. It represents the embryologic vestigial remnant of climbing animals and seen in many reptiles, most marsupials, cats, lemurs and American monkeys. The present study aims at the determination of incidence of the supracondylar process of humerus in the population of Assam. Materials and methods: 80 adult dry humeri were collected from Anatomy Department, Gauhati Medical College and were examined. Results: Out of 80 humeri, we found one humerus of left side with a bony projection from antero-medial surface of its distal shaft. The bone was then examined, studied, photographed and its dimensions were recorded. Conclusion: Knowledge of this variation may be of great importance to anatomists and anthropologists, because of possible link to the origins and relations of the human races. Introduction Race estimation from skeletal data has always been a central focus in anthropology1. Also, knowledge of variations in anatomy which is important to anatomists, radiologists, anesthesiologists and surgeons, has gained more importance due to wide use and reliance on computer imaging in diagnostic medicine2. Morphological differences are the tools being used to find the missing links between the different stages of evolution. One of such variations is the “supracondylar” processes. The spur of the humerus or supracondylar process was first reported by Struthers in 1849. It has been referred to as the “supraepitrochlear”, “supracondyloid” “epicondyloid” or “a supratrochlear spur” by various authors3. It is a normal anatomical structure in climbing animals4. In human, it is a rare, anomalous, beaklike bony process on the anteromedial surface of the humerus. It represents the embryologic vestigial remnant of climbing animals and seen in many reptiles, most marsupials, cats, lemurs and American monkeys5. It is usually found 5 - 7 cm above the medial epicondyle. The process projects anteroinferomedially from the distal third of the humerus and presents in 0.7 to 2.7% of the population 4. A ligament called Struthers’ ligament extends from the apex of the process to the medial epicondyle3. Materials and methods The study was conducted on 80 humeri which were collected from the 1 st M.B.B.S students and from the osteology laboratory, Department of Anatomy, Gauhati Medical College. The bones were examined for any osseous projection from distal part under day light. Only one humerus of left side was found with an osseous spine on its distal anteromedial surface. Dimensions of the projection were recorded by a vernier calliper and the incidence was calculated. Results The bony projection was extending obliquely, medially and downward from the anteromedial surface of the distal humeral shaft approximately 4.4 cm above the medial epicondyle. This spine was reported & referred to as supracondylar process. Table1. Showing various measurements of the supracondylar process (bony spine) Measurement Of Spine (supracondylar Value(in cm) process) Length of spine 1.1 Distance of spine from medial epicondyle 4.4 Distance of spine from nutrient foramen 6.5 Breadth at the base of spine 1.5 The incidence calculated in this study is- 1 X 100 = 1.25% 80 Discussion Incidence varies according to report given by different authors. Percentage of incidence according to different authors in different population along with incidence determined from this study in the population of Assam are shown belowTable2: Showing incidence of supracondylar process reported in different studies SI.No. Author Incidence Population / Race 1 Gruber17 (1865) 2.7% European race 2 Danforth18 (1924) 0.5% Mixed (Review) 3 Adachi19 (1928) 0.8% Mixed (Review) 4 Terry12 (1930) 1.16 5 Terry12 (1930) 0.1% 6 Hrdlicka20 (1923) 7 Dellon21 (1986) 1.15% European race 8 Parkinson5 (1954) 0.4% Mixed population 9 Natsis22 (2008) 1.3% Caucasians 10 Gupta23 (2008) 0.26% Indians 11 Present study 1.25% Assam 1% European race Negroes American Indians There is a high incidence of unilateral supracondylar process of the humerus in 'Cornelia de Lange syndrome', an autosomal recessive trait, occurring in approximately one in every 10,000 live births6. It is usually clinically silent, but may become symptomatic by presenting as a mass or can be associated with symptoms of median nerve compression and claudication of the brachial artery7. The process ends in a roughened point at which a dense fibrous band (ligament of Struthers) continues to the medial epicondyle 5. From embryological point of view, the Struthers ligament lies between the tendon of the latissimus dorsi and the coracobrachialis and corresponds to the lower part of the tendon of the vestigial latissimo-condyloideus, a muscle found in climbing mammals which extends from the tendon of insertion of the latissimus dorsi muscle to the medial epicondyle8. Rarely, this fibrous band may ossify forming a supracondylar foramen, a tunnel which transmits the median nerve and the brachial artery and sometimes a variant ulnar artery9 or the ulnar nerve10. In lower mammals, the osseo-fibrous tunnel formed by the humerus, supracondylar process and the Struthers’ ligament serves to protect the nerves and vessels going to the forearm10. In human, the presence of supracondylar process and the Struthers’ ligament is usually asymptomatic, but also it is an important entrapment site for the median nerve and brachial artery. Entrapment of brachial artery and median nerve by this ligament at the level of supracondylar process is known as the supracondylar process syndrome which can be treated by surgical removal of the process and ligament11. The compression symptoms include severe paresthesia and hypersthesia of the hand and fingers, ischemic pain of the forearm, embolization of the distal arm arteries and disappearance of the radial or ulnar pulse on full extension and supination of the forearm8,10,16. More rarely, ulnar nerve compression can also occur if the fibromuscular band from the process, instead of being attached to the medial epicondyle, extends downward as a band which blends with the fibrous arch between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris13,14,15. The anterior surfaces of the humerus are also covered by the brachialis muscle. The spine is thus likely to be within the sub-stance of the brachialis muscle. This could probably impair the function of the muscle3. Terry (1925) states that supracondylar process gives rise to the pronator teres, and occasionally affords insertion to a persistent lower part of the coracobrachialis12. A supracondylar process should be differentiated from osteochondroma. The spur is oriented distally, towards the elbow joint and there is no discontinuity in the cortex of the humerus. An osteochondroma points away from the joint. X-ray films of the supracondylar process show an intact underlying humeral cortex, whereas in an osteochondroma, the cortex of the tumor is continuous with the humeral cortex. Heterotopic bone such as myositis ossificans may also mimic a supracondylar process14. The anteroposterior radiographic view is most important since the lateral view may fail to show the spur on the anteromedial surface of the humerus14. Treatment consists of excision of the supracondylar spur and the associated ligament of Struthers. The spur has been reported to recur, and it is therefore recommended that the spur be removed together with the overlying periosteum24,25. CONCLUSION: We documented the incidence of supracondylar process as 1.25 % in the population of Assam. The supracondylar process is frequently misjudged as a pathological condition of the bone rather than as a normal anatomical variation. Though the supracondylar process is a very rare vestigial structure in humans, yet it is known to have racial variations. Our finding is closer to 1.3% as reported by Natsis (2008) studied in caucasian population. Along with the anatomists and anthropologists, the supracondylar process is equally important for clinicians as it may be overlooked and there may be misdiagnosis. Reference 1. William PL, Bannister LH, Berry MM, Collins P, Dyson M, Dussek JE, Ferguson MWJ, (Ed).Gray’s Anatomy. 38th Ed. Churchill Livingstone. New York,1999:626. 2. Harry WG, Bennett JD, Guha SC. Scalene muscles and the brachial plexus: anatomical variations and their clinical significance. Clin. Anat. 1997; 10: 252. 3. Oluyemi Kayode A, Okwuonu Uche C, Adesanya Olamide A, Akinola Oluwole B, Ofusori David A, Ukwenya Victor O and Odion Blessing I. Supracondylar and infratubercular processes observed in the humeri of Nigerians. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2007 Novemver 5; Vol. 6 (21), pp. 2439-2441. 4. Aydinlioglu A, Cirak B, Akpinar F, Tosun N, Dogan A. Bilateral Median Nerve Compresion at the Level of Struthers’ Ligament. J. Neurosurg. 2000; 92: 693-696. 5. Parkinson C. The supracondylar process. Radiology. 1954; 62: 556-558. 6. Peters FLM. Radiologic manifestations of the Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 1975; 3:41-46. 7. Subasi M, Kesemenli C, Necmioqlu S, Kapukaya A, Demirtas M. Supracondylar process of the Humerus. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2002; 68 (1):7275. 8. Kessel L, Ring M. The supracondylar spur of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg. 1976; 48:765-766. 9. Barnard LB, Mccoy SM. The supracondyloid process of the humerus, J Bone Joint Surg, 1946; 28(4):845–850. 10.Mittal RL, Gupta BR. Median and ulnar-nerve palsy: an unusual presentation of the supracondylar process. Report of a case, J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1978; 60(4):557–558. 11.Pecina M, Boric I, Anticevic D. Intraoperatively Proven Anomalous Struthers’ Ligament Diagnosed by MRI. Skeletal Radiol. Sep 2002; 31(9): 532-535. 12.Terry RJ. On the Racial Distribution of the Supracondyloid Variation. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol., 1930; 14: 459-462. 13.Al-Qattan MM, Husband J.B. Median nerve compression by the supracondylar process:A case report. J. Hand Surg. 1991; 16B: 101-103. 14.Fragiadakis EG, Lamb DW. An unusual case of ulnar nerve compression. Hand, 1970; 2: 14-16. 15.Thomsen PB. Processus supracondyloidea humeri with concomitant compression of the median nerve and the ulnar nerve. Acta Orthop. Scand., 1977; 48: 391-393. 16.Talha H, Enon B, Chevalier JM, L’hoste P, Pillet J. Brachial artery entrapment: compression by the supracondylar process, Ann Vasc Surg, 1987; 1(4):479–482. 17.Gruber, W.; Ein Nachtrag zur Kenntnis des Processus supracondyloideus (internus) humeri des Menschen. Arch. Anat. Physiol. Wissen. Med. 1865; 267:367-376. 18.Danforth CH. The Heredity Of Unilateral Variations In Man; Genetics; 1924; 9: 199. 19.Adachi B. Das Arteriensystem der Japaner. Verlag der KaiserlicheJapanische University zu Kyoto, Kenyusha Press, Tokyo.1928. 20.Hrdlicka, A. Incidence of the supracondyloid process in whites and other races. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.1923; 6:405-412. 21.Dellon, Lee. Musculotendinous variations about medial humeral epicondyle. Journal of Hand Surgery (Br), 1986; 11B: 175- 181. 22.Natsis K. Supracondylar process of the humerus: study on 375 Caucasian subjects in Cologne, Germany. Clin Anat. 2008 Mar; 21(2):138-41. 23.Gupta RK, Mehta CD. A Study of the Incidence of Supracondylar Process of the Humerus. J. Anat. Soc. India, 2008. 57 (2):111-115. 24.Ivins G K, Fulton MO. Supracondylar process syndrome : A case report. J. Hand Surg., 1996, 21-A, 279-281. 25.Spinner RJ, Lins RE, Jacobson SR, Nunley J A, Durham NC. Fractures of the supracondylar process of the humerus. J. Hand Surg. 1994, 19-A, 10381041. Fig 1: Showing left sided humerus with supracondylar process. Fig 2: showing only the distal part of the humerus with supracondylar process Fig 3: Showing the measurement of distance of supracondylar process from nutrient foramen with vernier calliper