VACCINATION IN PATIENTS WITH CIDP AND GBS

advertisement

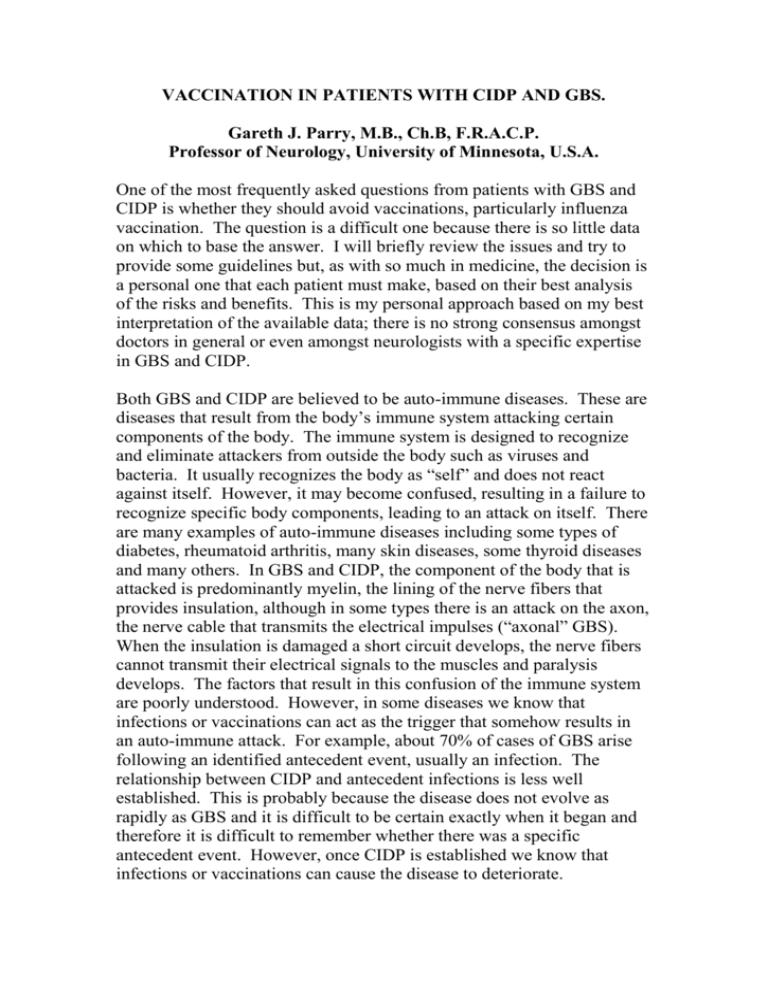

VACCINATION IN PATIENTS WITH CIDP AND GBS. Gareth J. Parry, M.B., Ch.B, F.R.A.C.P. Professor of Neurology, University of Minnesota, U.S.A. One of the most frequently asked questions from patients with GBS and CIDP is whether they should avoid vaccinations, particularly influenza vaccination. The question is a difficult one because there is so little data on which to base the answer. I will briefly review the issues and try to provide some guidelines but, as with so much in medicine, the decision is a personal one that each patient must make, based on their best analysis of the risks and benefits. This is my personal approach based on my best interpretation of the available data; there is no strong consensus amongst doctors in general or even amongst neurologists with a specific expertise in GBS and CIDP. Both GBS and CIDP are believed to be auto-immune diseases. These are diseases that result from the body’s immune system attacking certain components of the body. The immune system is designed to recognize and eliminate attackers from outside the body such as viruses and bacteria. It usually recognizes the body as “self” and does not react against itself. However, it may become confused, resulting in a failure to recognize specific body components, leading to an attack on itself. There are many examples of auto-immune diseases including some types of diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, many skin diseases, some thyroid diseases and many others. In GBS and CIDP, the component of the body that is attacked is predominantly myelin, the lining of the nerve fibers that provides insulation, although in some types there is an attack on the axon, the nerve cable that transmits the electrical impulses (“axonal” GBS). When the insulation is damaged a short circuit develops, the nerve fibers cannot transmit their electrical signals to the muscles and paralysis develops. The factors that result in this confusion of the immune system are poorly understood. However, in some diseases we know that infections or vaccinations can act as the trigger that somehow results in an auto-immune attack. For example, about 70% of cases of GBS arise following an identified antecedent event, usually an infection. The relationship between CIDP and antecedent infections is less well established. This is probably because the disease does not evolve as rapidly as GBS and it is difficult to be certain exactly when it began and therefore it is difficult to remember whether there was a specific antecedent event. However, once CIDP is established we know that infections or vaccinations can cause the disease to deteriorate. Development of GBS following vaccination is remarkably uncommon. The most highly publicized occurrence followed the influenza vaccination program in the United States in 1976. In anticipation of a potentially severe form of influenza (known as the swine influenza) arriving in the U.S. that year President Ford ordered a national vaccination program. Approximately 50 million people received the vaccine and the incidence of GBS following that vaccination was more than 20 times the expected incidence or the incidence in non-vaccinated individuals. However, the risk seems to have been attached to that specific vaccine. Prior to 1976 there had been only three cases of GBS following influenza vaccination despite very widespread vaccination programs and there has been no increase in the expected number of GBS cases following subsequent influenza vaccination programs, even though other vaccines have contained the swine ‘flu virus. Nor is there an established risk of developing GBS following other vaccinations. There has been a suggestion that one polio vaccination program in Finland was associated with a slight increase in the number of GBS cases. Similarly, there have been isolated reports of GBS following many other vaccines but there has been no consistent relationship that would indicate a predictable occurrence. All of this information pertains to populations who have never had GBS; i.e., these studies have looked at the incidence of GBS following vaccination in normal populations. A related issue is whether people who have recovered from GBS are at increased risk from vaccination. Recurrent attacks of GBS, although rare, do occur and have been described following vaccines, including influenza vaccines. Recurrence of GBS may also occur following infections such as influenza. In any given individual, the risk of developing another attack of GBS is probably no greater than developing the first attack; i.e., having had GBS probably does not make it more likely that an individual will have a second attack. In patients with CIDP there is probably a greater risk that vaccinations of any kind will produce a relapse of their disease. On the other hand, the relapse is seldom severe; there may be a minor increase in numbness and tingling or weakness but almost never life threatening problems such as breathing or swallowing difficulties. Furthermore, the relapses are usually responsive to standard CIDP treatment. It is important to remember that the risk of developing new GBS, having a recurrence of GBS or developing a relapse of CIDP are all considerably greater following an infectious illness such as influenza than it is after vaccination. Thus, by preventing the infection, vaccinations may actually reduce the risk of one of these undesirable outcomes. For many diseases, such as polio, typhoid, tetanus, rabies and others, the result of getting the disease is so devastating that it is easy to recommend the vaccine, even if it does cause GBS or CIDP. It is with the less severe diseases such as influenza that the difficulties arise. Furthermore, most of the conditions mentioned above require only a single vaccination in a life time while influenza vaccines are recommended each year. In making the decision about whether an individual who has had GBS should receive the influenza vaccine (or any other vaccine for that matter) I ask the following questions:1. Was the initial attack of GBS triggered by an influenza vaccine? 2. Was the initial attack of GBS triggered by influenza? 3. Is the individual at increased risk of significant complications of influenza? This includes individuals with chronic respiratory disease such as asthma, chronic bronchitis or emphysema, people over the age of 70 years and people with other serious chronic diseases. If the answer to either of the first two questions is affirmative while the third is negative then the risk of the vaccine, although very small, may outweigh any benefit. If the answer to the third question is affirmative while the first two are negative then the benefit of the vaccination clearly outweighs the slight risk that it will cause a recurrence of the GBS or relapse of CIDP. If all three are affirmative then I usually still recommend vaccination but certainly emphasize to the patient the potential risk.