Submissions for the Proposed Australian Biofouling Management

advertisement

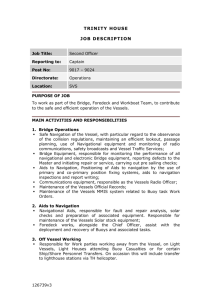

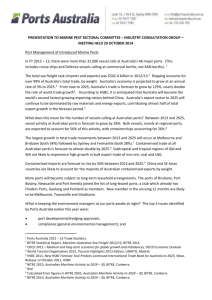

Submissions for the Proposed Australian Biofouling Management Requirements Consultation Regulation Impact Statement A submission received from GHD, Queensland Submission Q1. Do the proposed operating time restrictions on vessels achieve an appropriate balance between minimising biological risk (which increases with time) and minimising the impact on vessel operators (who may need more time)? If not, why and what would be a better balance? Information provided in regards to the proportion of vessels subject to OTR indicates that 44% of vessels could be affected. However, this could be an underestimate as it is not clear whether this accounts for vessels that do not spend longer than 48 hrs in a port but do breach other OTR. A consideration with forcing (potentially) 44% of vessels visiting Australian waters to be subject to an in-water pest inspection (or slippage) is the ability to service that demand requirement within the OTR. Further, it is not clear how this analysis deals with vessels that currently standby at anchor offshore of ports. Queuing at Australian ports likely would not align with the OTR or in-water inspection opportunities forcing vessels to queue elsewhere, which may have a flow on affect to our ability to export commodities. If vessels chose to queue in (e.g.) Singapore only mobilising to Australia to align with OTR the risk of the vessel housing a pest could increase. However, it could provide opportunity for vessels to achieve pre-entry inspections. Hence, it is unclear from the information provided the extent to which these OTR or requirement for in-water inspection may impost vessels. Further, insufficient knowledge is presented regarding the risk that a pest may be introduced within those OTR to clarify whether that risk is adequately managed. It is noted (Appendix D) that all SOC are assumed to have an equal probability of arrival, however, whether this also infers an equal probability of establishment is unclear. Section 14 Appendix D notes that all SOC are assumed an equal impact potential, which begins immediately upon establishment – not arrival. For this response it is assumed that arrival equates to establishment, for simplicity. In that regard, introduction risk could also consider frequency of inoculation, a proxy for which could be visitation frequency of vessels from known destinations. For common trading partners vessels have known operational runs between designated Australian and international ports. Identifying these operational routes and accounting for them in conjunction with hull cleanliness could better inform risk of translocation between those ports and enable targeted management. Given high risk vessels subject to OTR are required to leave Australian waters or be subject to a hull inspection in Australian waters if they cannot meet the OTR, the onus would be on Australian service providers to achieve inspection within the designated OTR. This would not be feasible for most of the geographies in Australia where these inspections may be required. Vessels would likely require longer than the OTR timeframe of 48 hours within a port to actually enable inspection to occur. This is reflected by the ‘opportunity costs of travelling’ being considered to be 4 days. How this time impost has been accounted for with regard to the OTR is unclear. Noting, of course, that in-water inspection does not provide opportunity to examine key niche environments for species of risk, primarily ballast intake points. As such, this approach may not reduce risk but provide a ‘false’ finding that a vessel is not a high risk vessel. Q2. How might vessel operators’ behaviour change in response to the proposed regulations? As noted above queuing at Australian ports awaiting loading of bulk export commodities may not be achievable within the OTR. Any change to this behaviour could have flow affects to the volume of trade achieved and the management of import/export operations for Australia. It is plausible that vessel operators could choose to be inspected more regularly or to achieve inwater cleaning outside of Australian waters, however, the level of change that may be executed in this regard is unclear. In-water cleaning of anti-fouling paints can decrease the life of the paint or its efficacy and may not address key niche areas such as ballast intakes. Q3. What specific types of flow-on costs and benefits to the Australian economy of the proposed regulations might be significant? Apart from the significant manpower within government to execute the entry checks and inspections, there would need to be an ability for in-water inspection or slippage of designated vessels to actually occur. Vessel inspections for pest SOC requires a set of skills which are not readily available in Australia currently to service the inspection demands which could be required. As such, Australia is not well positioned to support legislation of this nature. Of distinct concern is the lack of appropriately trained taxonomic specialists who could verify any detected specimens with regard to SOC status. Training new people for this role would be an upfront cost, but one which could have long term benefits to support this service provision in Australia. A key to success would, however, be provision of work opportunities for taxonomically trained persons to maintain them in this role capacity. If these persons were to be employed within government organisations in support of the biosecurity regulation funding to establish and maintain those roles would be a cost. Q4. The estimates of costs are based on average vessel numbers from 2002-2009. Is there any activity or trends that suggest any significant change in vessel movement or increased numbers of arrivals? Significant port expansion developments are currently occurring or are planned within a number of Queensland ports (at the minimum). There will, as a consequence, be a significant increase in vessel movements associated with these expansions. Those are likely not captured by the information supporting this RIS. Those ports are adjacent to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and would require anchorage within the park and transit through the park. Q5. Are the cost assumptions consistent with industry experience? (see appendix D for all cost assumptions). Are there better estimates of costs available? Introduction of a pest SOC may affect health, biodiversity and/or the economy. This can be related to an impact by the SOC on values of the receiving environment. Cost assumptions provided in the RIS (in part) reflect those costs incurred elsewhere to manage/respond to SOC incursions. They are a summary of experience from other geographies/incursions. Ecosystem service evaluation is an alternative approach used elsewhere to consider what costs may be realised from impacts to the environment. Similar could be applied here to support estimated costs of not managing risk of SOC introduction. The assumption that costs of verification and audit (refer Appendix D, Section 8) would be negligible is problematic. The ability to verify that the rating of ‘moderate’ to vessels is accurate is a different task to verifying that the ‘moderate’ fouled vessels do not carry SOC. The power to be sure of the finding will influence the number of vessels that need to be included in the audit for either approach. What is to be achieved through the audit task? Q6. Are the other assumptions used to estimate costs and benefits reasonable based on industry experience? If not, how could they be improved? No comment provided Q7. The methodology for estimating the economic value at risk relies on a series of assumptions about the value of commercial fishing and the Great Barrier Reef. Are there more plausible assumptions or approaches that could be used? Refer response provided under Q5 above – ecosystem service cost impacts could be used. Q8. What other evidence is there of the potential impacts of non indigenous marine species becoming established in Australia? No comment provided Q9. What is industry’s view of the likely effectiveness of a voluntary approach to reducing the risks associated with biofouling compared to a regulatory approach? While industry has to bear all costs with no regulatory “stick” as a motivator uptake of any additional maintenance over and above that nominated as appropriate for their vessels antifouling system management (specifically for SOC management) is likely to be low. Some higher risk activities are currently pseudo-regulated. For instance, some development projects are currently conditioned to require internationally sourced vessels to be free of marine pests of concern prior to entry to Australian waters. Q10. Do you have any other comments on the Regulation Impact Statement? Promotion of in-water inspection as a clearance of a vessel from SOC to reduce its risk categorisation provides concern for reasons including: some SOC are not able to be detected visually using in-water inspection – either because they are cryptic or of a physical size/nature to not be detected by any form of visual inspection diving is not a safe practice in all locations which would receive vessels which may require in-water inspection Qualifications could be provided to the RIS to note the ‘risks’ associated with clearing a vessel using visual inspection, particularly if achieve in-water by divers. How these risks compound or have been accounted for in determining the efficacy of each approach in terms of managing risk of SOC introduction should also be clarified. As noted under Q1, in forming this response it has been assumed that the RIS considers that arrival of a SOC equates to establishment. This may be discussed in the RIS, however, it was unclear at the time of reading. The process of infestation, and the chance of an introduced species becoming established and developing a population that causes economic, social or environmental harm is a complex one. It is expected that is well understood by the team that has developed the RIS, however, the assumptions made regarding what is considered to be an impactive introduction could (it is felt by this reader) be clearer. What consequences of breaching the legislation would be applied is not understood. Comments have been provided under Q5 regarding audit checks and how these may be time consuming and potentially costly. A cynical perspective could suggest that cost of vessel operators applying management measures to reduce their risk ranking could be weighted against the cost of incurring a fine if detected. Which would influence vessel operators adherence to this management for biofouling species even if regulated. It is expected that education of industry would be combined with implementation of regulation to influence a desire in industry to assist in management of SOC introduction risks.