VISUAL SURVEY METHODS

advertisement

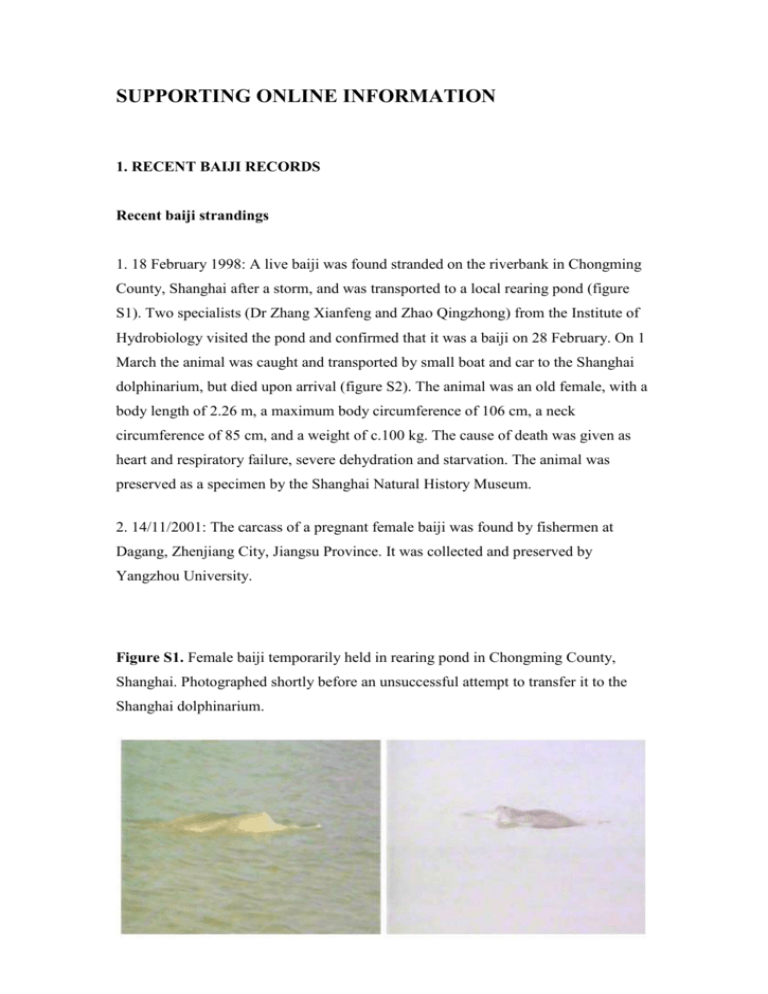

SUPPORTING ONLINE INFORMATION 1. RECENT BAIJI RECORDS Recent baiji strandings 1. 18 February 1998: A live baiji was found stranded on the riverbank in Chongming County, Shanghai after a storm, and was transported to a local rearing pond (figure S1). Two specialists (Dr Zhang Xianfeng and Zhao Qingzhong) from the Institute of Hydrobiology visited the pond and confirmed that it was a baiji on 28 February. On 1 March the animal was caught and transported by small boat and car to the Shanghai dolphinarium, but died upon arrival (figure S2). The animal was an old female, with a body length of 2.26 m, a maximum body circumference of 106 cm, a neck circumference of 85 cm, and a weight of c.100 kg. The cause of death was given as heart and respiratory failure, severe dehydration and starvation. The animal was preserved as a specimen by the Shanghai Natural History Museum. 2. 14/11/2001: The carcass of a pregnant female baiji was found by fishermen at Dagang, Zhenjiang City, Jiangsu Province. It was collected and preserved by Yangzhou University. Figure S1. Female baiji temporarily held in rearing pond in Chongming County, Shanghai. Photographed shortly before an unsuccessful attempt to transfer it to the Shanghai dolphinarium. Figure S2. Unsuccessful attempt to translocate female baiji from rearing pond to Shanghai dolphinarium on 1 March 1998. Recent sightings of live baiji Date 16/04/2000 17/04/2000 18/04/2000 20/04/2000 22/01/2001 27/05/2001 29/05/2001 29/05/2001 29/05/2001 30/05/2001 23/07/2001 23/11/2001 30/11/2001 05/01/2002 08/03/2002 09/03/2002 14/03/2002 30/04/2002 22/05/2002 02/06/2002 16/12/2002 28/02/2003 - /05/2004 16/07/2004 17/09/2004 - /- /2005 - /03/2006 - /05/2006 Section Tongling Tongling Tongling Tongling Tongling Tongling Tongling Tongling Tongling Tongling Tongling Tongling Honghu Honghu Honghu Honghu Tongling Tongling Tongling Honghu Honghu Tongling Tongling Honghu Tongling Honghu Honghu Honghu Number 1 2 2 2 1 1 3 2 1 1 2 1 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 1 3 1 2 Eyewitness ----------------Fisherman Fisherman Reserve staff ------Fishermen Fishermen Local Marine Affairs Administration staff Reference Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Note 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Ref. 1 Note 2 Note 3 Note 4 Table 1. Reported baiji sightings from 2000 until start of 2006 range-wide survey. Notes: 1. See figure S3. 2. Data source: Xiong Yuanhui, Honghu (Xin-Luo) National Baiji Reserve staff, cited in unpublished Honghu Reserve report submitted to Chinese Ministry of Agriculture, December 2006. 3. A local fisherman observed a baiji less than 100 m from the bank in the Paizhou area. The animal only surfaced once. Data source: see note 2. 4. Two staff from the local Maritime Affairs Administration observed two baiji swimming downstream at 100 m distance from the bank in the port area of Paizhou. The animals surfaced three times and then disappeared. One of the witnesses had previously visited the IHB dolphinarium in Wuhan and seen the captive baiji ‘Qi Qi’ before its death in 2002, and so is regarded as a reliable witness able to distinguish between baiji and finless porpoises. Data source: see note 2. Opportunistic baiji sightings were primarily reported to IHB staff by fishermen employed by the Baiji Monitoring Network in the Honghu National Baiji Reserve and Tongling Provincial Baiji Reserve. The predominance of baiji records from these two river sections therefore reflects a lack of monitoring effort elsewhere along the river, rather than necessarily indicating the absence of baiji in other sections of the Yangtze after 2000. During the 2006 survey, a possible sighting of two baiji was reported to IHB staff by retired schoolteacher Jian Bingzhang, who was doing morning exercises 2-3 m from the shore at Huangshi Beach Park, Hubei Province, between 0800-0900 on 02/12/2006 with a colleague when he saw two cetaceans swimming downstream. He stated that the animals were 60-70 m from the bank and 20 m apart, and disappeared after surfacing three times (Jian himself saw the animal break the surface twice, and then told his colleague, who saw it surface a third time). The animals were identified as baiji rather than finless porpoises because both individuals apparently had dorsal fins. There was no glare interference during the period of the sighting. It is impossible to evaluate such opportunistic sightings made by non-specialists. However, it is important to note that several finless porpoises were observed during the 2006 survey rolling sideways and exposing their pectoral fins; these superficially appeared to be dorsal fins, making the porpoises resemble baiji on initial viewing even to experienced observers. Figure S3. Two photographs of a single baiji in Tongling Reserve on 22 May 2002. This represents the last authenticated sighting of a baiji in the wild. 2. NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2006 SURVEY METHODS Visual survey methods Two 36 m vessels (KeKao No. 1 and Honghu) surveyed the entire historical range of the baiji in the main channel of the Yangtze from Yichang to Shanghai, travelling upstream from Wuhan to Yichang, then downstream to Shanghai and back upstream to Wuhan. The survey was designed both to maximize the probability of finding baiji, and to estimate the abundance of the sympatric Yangtze finless porpoise. Observation stations were approximately 4 m above the river surface on the exposed roof of the bridge of each vessel and had unobstructed 360º viewing. Vessels maintained a speed of approximately 15 km/hour and a maximum distance of 300 m from the nearest bank. Going upstream, KeKao No. 1 covered the north side of the Yangtze channel and Honghu covered the south side; positions were reversed going downstream, so that each vessel covered the survey area independently. The two vessels surveyed roughly the same section of the river each day, but maintained a separation of approximately 3-5 km, to ensure that sighting probabilities remained Figure S4. Histogram of total survey effort under different weather conditions during the November-December 2006 Yangtze cetacean survey. _____________________________________ independent. When there were navigable channels on both sides of an island or sand bar, vessels coordinated their efforts to cover both channels (unless only one channel was navigable); however, the survey trackline was often restricted to the main Yangtze shipping lane because of regional navigation laws. When sighting conditions were too poor to allow observation (e.g. due to fog, rain and/or high wind), the vessels stopped and resumed the survey when conditions improved (figure S4). The boats were tied together each night, so scientists could meet to discuss the day’s events and prevent protocol differences from developing. Each vessel carried two highly experienced marine mammal observers, who acted as independent observers (IOs), and 5-6 primary observers (POs) with prior experience in observing finless porpoises and/or other small cetacean species. Observers were distributed during survey effort in the same configuration on both vessels (figure S5). -10 left +10 right recorder -90 +90 Figure S5. Areas covered by the primary observers: left observer -90° to +10°, right observer -10° to +90°, recorder -90° to +90°. The independent observer was positioned on the raised platform (represented by the square), or on the mounted 25× Fujinon binoculars (represented by the circle). POs rotated every 30 minutes through three positions – left observer, data recorder and right observer – and then rested for 60-90 minutes. 7×50 power hand-held binoculars were used for surveying, mounted on a 45 cm central wooden staff that could be held at waist level to reduce fatigue. POs were instructed to constantly scan their areas primarily with binoculars but occasionally with naked eyes, to minimise the risk of not detecting cetaceans surfacing close to the survey vessels. At the beginning of each rotation, the new recorder would record the following information on the data sheet: time, distance and direction to nearest bank, overall sighting conditions (poor, fair, good or excellent), observers on watch, and passing or closing mode (see below). Every 10 minutes, distance to the nearest bank was recorded using a digital laser rangefinder, and each vessel’s position was recorded using a GPS. Data sheets and GPS positions were inputted or downloaded to a computer each evening. When a cetacean sighting was made, the observer estimated distance of the animal(s) to the vessel and to the nearest bank, angle (read from an angle board), group size, and coded habitat type. During the rest period the sighting observer completed a more detailed form for each sighting indicating specific identification features and behaviour. Distances of groups of porpoises from the vessel and the nearest bank were estimated by eye, and observers were instructed to practice estimating distances using the laser rangefinder on the numerous other vessels and buoys on the river, with a distance calibration exercise conducted every week for all members of the survey team. The primary purpose of the IOs was to gather data to allow the estimation of the probability of detecting animals on the trackline g(0), a critical parameter for linetransect analyses2. Because POs varied in their level of experience, the IOs could also focus their attention where their greater experience was most needed. Both baiji and finless porpoises surface briefly and have intervals beneath the surface lasting up to several minutes3-8, and so having the area ahead of the vessel covered by at least three observers at all times (i.e., even when the recorder was not looking) was necessary to maximize the chances that animals are sighted. Sightings by the IOs were recorded in separate notebooks, and then given to the recorder during a subsequent off-effort rest period. If IOs thought that a poor estimate was made of group size and their boat was in closing mode (see below), they could request to suspend the survey effort and return to the sighting to get a better estimate. Survey protocol differed slightly for each vessel to maximize the ability both to detect baiji and to obtain an abundance estimate for finless porpoises. IOs on KeKao No. 1 used only mounted 25× Fujinon binoculars (‘big eyes’) to maximize the ability to detect baiji at greater distances. Increasing detection distance was needed for sections of the river that could not be approached closely by either boat and where observers were unlikely to detect baiji using 7× binoculars. These areas tended to be behind river bars or up tributaries or side-channels (most of which were non-navigable). During the first part of the survey from Wuhan-Shanghai, the IOs on Honghu instead used 7×50 binoculars, and stood on a 20 cm high platform immediately behind the primary observers. This allowed them to see over the POs, and to calibrate PO sighting probabilities, but did not appreciably increase the detection distance. During the second part of the survey, IOs focused their effort on detecting baiji, and spent time opportunistically scanning tributaries, side channels, and behind river bars as well as the area from -90° to +90° on the survey trackline. The IOs on Honghu also switched to using ‘big eyes’. Although each vessel was instructed to radio the other one if baiji were detected, the survey design ensured that both vessels were completely independent, i.e. did not cue each other about sightings. This independence was necessary for an unbiased estimate of finless porpoise abundance. Vessels traded roles daily, between ‘passing’ (in front) and ‘closing’ (behind) modes. The closing mode vessel would ‘close’ on sightings where group size was in question, i.e. suspend effort and spend time with groups of animals to estimate group size. When the leading vessel had a sighting with a poor estimate of group size, observers would radio the trailing vessel after they deemed the sighting to be sufficiently far behind that the second vessel would also have passed it. This method worked best if observers on the two vessels could still be seen by one another (within about 3 kilometres), as observers on the leading vessel could judge the position of the trailing vessel relative to the sighting. Because in previous surveys baiji had sometimes been observed associating with groups of finless porpoises3,7,9, the additional time spent obtaining accurate porpoise group size estimates also provided further opportunity for observers on the closing mode vessel to investigate whether baiji were also present. The survey design was broadly similar to the approaches used by Chinese scientists to count baiji in the past3,9. However, there were some noteworthy differences. The surveys of the lower reaches of the Yangtze in 1989-1991 involved 4-8 fishing boats with outboard engines travelling side-by-side at speeds of 7-8 km/hr [ref. 9]. Each boat had two primary observers described as ‘trained fishermen operators/observers’. Platform height was not reported but presumably was close to water level on at least some of the boats. Evidently searching was without the aid of binoculars. The surveys of the middle and lower reaches (and including both Dongting and Poyang Lakes) in 1997-99 also involved multiple boats – two per section covering 16 river sections simultaneously – and more than 300 people3. Platform height varied from 2-4 m; the boats travelled in parallel along opposite sides of the channel at speeds of 8-12 km/hr; and three trained observers on each boat (at least one of them ‘experienced’) searched for baiji with hand-held 7× to 10× power binoculars. Mounted ‘big eye’ binoculars, stick supports for regular binoculars, and a strictly observed rotation schedule to reduce fatigue were not used in any of these previous surveys. In our 2006 survey the same two vessels, each manned by a team of experienced observers, carried out the entire survey, and the platform height of our vessels was equal to that of the largest boat involved in the 1997-1999 surveys3. In addition, none of the previous surveys included an acoustic detection component. The only aspect of our 2006 survey methodology that might be viewed as disadvantageous in comparison to previous Yangtze surveys is the faster reported vessel speed: 15 km/hr versus 7-8 km/hr [ref. 9] or 8-12 km/hr [ref. 3]. Comparison of porpoise sighting data from KeKao No. 1 and Honghu indicates that both vessels independently detected very similar numbers of porpoises in the Yangtze, both on a daily basis and over the course of the survey (figure S6; tables S2-3). This close correspondence in porpoise sightings between the two vessels is persuasive evidence that no baiji were missed in the main Yangtze channel by the survey teams. Figure S6. Count of daily finless porpoise sightings over the course of the NovemberDecember 2006 baiji survey by KeKao No. 1 and Honghu (excluding porpoises counted in the mouth of Poyang Lake), showing close correspondence in survey effectiveness between the two vessels. Upstream Downstream Subtotal On-effort PO 185/147 163/162 348/309 Off-effort IO 58/51 54/68 112/119 Subtotal 243/198 217/230 460/428 29/15 21/13 Table S2. Total numbers of individual finless porpoises seen during the 2006 survey by the two survey vessels (KeKao No. 1/Honghu). Upstream Downstream Subtotal On-effort PO 100/73 76/77 176/150 Off-effort IO 35/28 34/34 69/62 Subtotal 135/101 110/111 245/212 11/4 10/4 Table S3. Total numbers of finless porpoise sighting events during the 2006 survey by the two survey vessels (KeKao No. 1/Honghu). Acoustic survey methods One vessel also carried a full-time acoustic survey team consisting of two on-effort researchers using a towed hydrophone (C54XRS with 87 m cable, Cetacean Research Technology). The acousticians listened continuously for potential baiji whistle signals in real time for the entire duration of the survey. An acoustic baiji database, obtained in 1996 from a translocated free-ranging female baiji held in the Tian’e-Zhou National Baiji Reserve, demonstrates whistle signals with a frequency range between 3.8 kHz and 6.8 kHz (figure S7, Electronic Appendix Audio File) [ref. 10]. We monitored the frequency band from 4-6 kHz to focus on the fundamental frequency component of the baiji’s whistle, using a band pass filter (NF3611) to eliminate background noise. The whistle’s source level calculated by ref. 10 was 143.2 dB rms re 1 uPa (s.d.=5.8). This amplitude was approximately 50 dB higher than the band noise level when towing low frequency hydrophones on the downstream portions of the survey. Under these ambient conditions, the detection distance of a baiji whistle was estimated to be 300 m, assuming simple omni-directional/spherical sound propagation. However, when travelling upstream the background noise level was only 10-20 dB higher than baiji source levels, because of the higher relative speed of the vessel against the water current in the river. Figure S7. Sonogram of whistle of a free-ranging baiji recorded in 1996. The acoustic baiji database indicates that the animal recorded in 1996 produced whistles with an average silent interval of 205 s (s.d.=254). Assuming a constant speed of 15 km/hour, the survey vessel travelled 854 m during this time interval, and the maximum detection range from the hydrophone was 300 m in any direction. This means that the acoustic monitoring system would have been able to detect approximately 70% of the baiji encountered directly on the survey trackline. However, as the width of the river varied from several hundred metres to a few kilometres, the overall coverage probability across the baiji’s historical range in the main Yangtze channel would have been substantially lower than 70%. References 1. Braulik, G. T., Reeves, R. R., Wang, D., Ellis, S., Wells, R. S. & Dudgeon, D. Report of the workshop on conservation of the baiji and Yangtze finless porpoise. Baiji.org Foundation, Zurich (2005). 2. Buckland, S. T., Anderson, D. R., Burnham, K. P., Laake, J. L., Borchers, D. L. & Thomas, L. Advanced distance sampling: estimating abundance of biological populations. Oxford Univ. Press (2004). 3. Zhang, X., Wang, D., Liu, R., Wei, Z., Hua, Y., Wang, Y., Chen, Z. & Wang, L. The Yangtze River dolphin or baiji (Lipotes vexillifer): population status and conservation issues in the Yangtze River, China. Aquatic Conserv.: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 13, 51-64 (2003). 4. Zhou, K. & Li, Y. Status and aspects of the ecology and behavior of the baiji, Lipotes vexillifer, in the lower Yangtze River. Occ. Papers IUCN SSC 3, 86-91 (1989). 5. Hua, Y., Zhao, Q. & Zhang, G. The habitat and behavior of Lipotes vexillifer. Occ. Papers IUCN SSC 3, 92-98 (1989). 6. Liu, R., Yang, J., Wang, D., Zhao, Q., Wei, Z. & Qang, X. Analysis on the capture, behavior monitoring and death of the baiji (Lipotes vexillifer) in the Shishou semi-nature reserve at the Yangtze River, China. IBI Reports 8, 11-21 (1998). 7. Würsig, B., Breese, D., Chen, P., Gao, A., Tershy, B., Liu, R., Ding, W., Würsig, M., Zhang, X. & Zhou K. Baiji (Lipotes vexillifer): travel and respiration behavior in the Yangtze River. Occ. Papers IUCN SSC 23, 49-53 (2000). 8. Akamatsu, T., Wang, D., Wang, K., Wei, Z., Zhao, Q. & Naito, Y. Diving behaviour of freshwater finless porpoises (Neophocaena phocaenoides) in an oxbow of the Yangtze River, China. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 59, 438-443 (2002). 9. Zhou, K., Sun, J., Gao, A. & Würsig, B. Baiji (Lipotes vexillifer) in the lower Yangtze River: movements, numbers threats and conservation needs. Aquat. Mamm. 24.2, 123-132 (1998). 10. Wang, K., Wang, D., Akamatsu, T., Fujita, K., Shiraki, R. Estimated detection distance of a baiji's (Chinese river dolphin, Lipotes vexillifer) whistles using a passive acoustic survey method. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 120, 1361-1365 (2006).