What complications could arise from this case

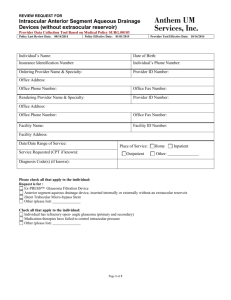

advertisement

What complications could arise from this case? Retinal Detachment The complications that could arise from retinal detachment are blindness, formation of an epiretinal membrane, optic nerve disorder and photopsia. The retina, a light-sensitive layer of tissue that lines the inside of the eye sends visual messages through the optic nerve to the brain. When the retina detaches, it is lifted or pulled from its normal position, away from the choroid which supplies it with nutrient and oxygen. If not treated promptly, detached retina will lead to permanent vision loss. Epiretinal membranes have been commonly found in association with ocular trauma, retinal breaks and detachments. They occur as a result of retinal glial cell proliferation along the surface of the ILM. Small, focal defects in the ILM allow these cells to "break through" to the retinal-vitreous interface and reproduce, creating a thin veil of tissue. Localized epiretinal membranes may occur at the posterior pole of the eye without clinical signs or may cause marked loss of vision as a result of covering, distorting, or detaching the fovea centralis. Epiretinal membranes may cause vascular leakage and secondary retinal edema. Photopsia which is the perception of flashes of lights by the patient is almost always a result of retinal detachment. It probably arises from the separation of the posterior vitreous.As the vitreous gel separates from the retina, it stimulates the retinal tissue mechanically, resulting in the release of phosphenes and the sensation of light. It may be induced by eye movements and appears to be more noticeable in dim illumination. Hyphema Complications of traumatic hyphema may be directly attributed to the retention of blood in the anterior chamber. The four most significant complications include posterior synechiae, peripheral anterior synechiae, corneal bloodstaining, and optic atrophy. Posterior synechiae Posterior synechiae may form in patients with traumatic hyphema. This complication is secondary to iritis or iridocyclitis. However, they are relatively rare complications in patients who are medically treated. Posterior synechiae occur more frequently in patients who have had surgical evacuation of the hyphema. Peripheral anterior synechiae Peripheral anterior synechiae occur frequently in medically treated patients in whom the hyphema has remained in the anterior chamber for a prolonged period, typically 9 or more days. The pathogenesis of peripheral anterior synechiae may be due to a prolonged iritis associated with the initial trauma and/or chemical iritis resulting from blood in the anterior chamber. Alternately, the clot in the chamber angle may subsequently organize, producing trabecular meshwork fibrosis that closes the angle. Both mechanisms are likely to be involved. Corneal bloodstaining Corneal bloodstaining primarily occurs in patients with a total hyphema and associated elevation of intraocular pressure. The following factors may increase the likelihood of corneal bloodstaining; all of these factors affect endothelial integrity: * Initial state of the corneal endothelium; decreased viability resulting from trauma or advanced age (eg, cornea guttata) * Surgical trauma to the endothelium * Large amount of formed clot in contact with the endothelium * Prolonged elevation of intraocular pressure Corneal bloodstaining may occur with low or normal intraocular pressure; rarely, it may also occur in less than total hyphemas. However, these latter 2 instances probably can be anticipated only in eyes with a severely damaged or compromised endothelium. Corneal bloodstaining is more likely to occur in patients who have a total hyphema that remains for at least 6 days with concomitant, continuous intraocular pressures of greater than 25 mm Hg.4 Clearing of the corneal bloodstains may require several or many months. Generally, the corneal bloodstains form centrally and then spread to the periphery of the corneal endothelium. During resolution, corneal bloodstaining clears peripherally and then centrally, reversing the sequence of the initial staining process. Optic atrophy Optic atrophy may result from either acute, transiently elevated intraocular pressure or chronically elevated intraocular pressure; each occurrence was studied in a series of patients with hyphema in an attempt to identify predisposing factors. Nonglaucomatous optic atrophy in patients with hyphema may be due to either the initial trauma or the transient periods of markedly elevated intraocular pressure. Diffuse optic pallor (and not glaucomatous cupping) is the result of transient periods of markedly elevated intraocular pressure. Pallor occurs with constant pressure of 50 mm Hg or higher for 5 days or 35 mm Hg or higher for 7 days. The authors have observed numerous patients with sickle cell trait who developed a nonglaucomatous optic atrophy with relatively low elevations of intraocular pressure of 35-39 mm Hg for 2-4 days.4 In spite of maximum medical therapy, final visual acuity was less than 20/400 in all patients. The authors continue to observe optic atrophy in patients with sickle cell trait who are referred to their institution and who have not had vigorous control of intraocular pressure and/or delay in paracentesis. Other studies indicate that patients with sickle cell hemoglobinopathies and anterior chamber hyphemas have more sickled erythrocytes in their anterior chambers than in their circulating venous blood.21 The sickled erythrocytes obstruct the trabecular meshwork more effectively than healthy cells, and a consequent elevation of intraocular pressure occurs with lesser amounts of hyphema. Systemic hypotensive agents, such as acetazolamide and methazolamide, may not always be successful in reducing the intraocular pressure. In fact, they may be contraindicated in high or repeated dose regimens because of their possible contribution to intravascular hemoconcentration and increased microvascular sludging, both of which are detrimental in sickle cell hemoglobinopathy. The increased intraocular pressure may not be tolerated well in these patients because of the increased susceptibility to impaired vascular perfusion within the optic nerve and the retina. Indeed, moderate elevation of intraocular pressure in patients with sickle cell hemoglobinopathy may produce rapid deterioration of visual function because of profound reduction of central retinal artery and posterior ciliary artery perfusion. For African American patients, the prevention of secondary hemorrhage is a critical factor. Other complications associated with hyphema involve disruption of the posterior segment. These complications include, but are not limited to, choroidal rupture, macular scarring, retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, and zonular dialysis. Even a case of sympathetic ophthalmia following hyphema has been reported.