Lecture C1. Exposure of intraabdominal organs, technical aspects of

advertisement

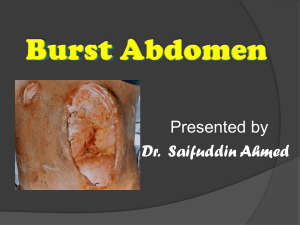

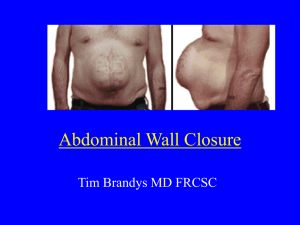

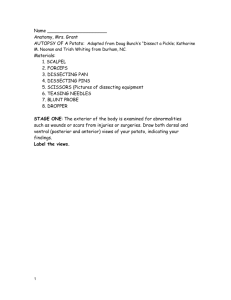

Lecture C1. Exposure of intraabdominal organs, technical aspects of laparotomy 1. Lecture C2. Incisions, exposure of intraabdominal organs 2. Appendectomy What is a „Modul”? A curricular structure to... - update new scientific and medical findings relevant to medical practice - enhance clinical reasoning and decision making - provide individual feedback and career advising Typical careers Surgery and surgical specialties, i. e. general, head and neck, plastics, thoracic, vascular, neurosurgery Gynecology Oncology Ophthalmology Orthopedics Urology Anesthesiology, emergency medicine, critical care Cardiology Goals - to foster skills-based decision making - to broaden the correlation of physiology, anatomy and pharmacology to acute clinical care Emphasis - procedures - critical thinking and assessment skills - to develop the knowledge and skills to support a career choice in those specialties in which expertise in anatomy/surgery is critical Format and topics Surgical principles taught on animals, including basic techniques and advanced interventions such as surgical operations, e.g. laparotomy, appendectomy and intestinal resection, bowel anastomosis and thoracotomy. General structure of lectures 1. History, background 2. Asepsis and antisepsis, complications 3. Anaesthesia 4. Anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology of the abdominal wall 5. Wound healing 6. Diagnostic and surgical interventions for a patient undergoing laparotomy 7. Intraoperative course for a patient undergoing acute and planned laparotomy, intraoperative problems 8. Appropriate patient position 9. Incisions used for the procedure 10. Procedural steps 11. Supplies, equipment, and instrumentation needed for the procedure 12. Postoperative care Terms and definitions Laparo-, lapar- (Greek:): the soft part of the body between the ribs and the hip; denotes the flank or loins and the abdominal wall. Sometimes this element is used loosely (even incorrectly) in reference to the abdomen in general. In surgery Cutting through the abdominal walls into the cavity of the abdomen; incision into the loin. Surgical incision through the flank; less correctly, but more generally, abdominal section at any point to gain access to the peritoneal cavity Laparotomy- investigation of abdominal pain • Emergency admissions: 50% of general surgical work load • Abdominal pain: 50% of emergency admissions • 70% of diagnoses can be made based on history alone. • 90% of diagnoses can be made based on history + physical exam. • Expensive tests: often confirm what is found during the history and physical examinations Conditions presenting with acute abdominal pain Condition % Non-specific abdominal pain 35 Acute appendicitis 17 Intestinal obstruction 15 Urological causes 6 Gallstone disease 5 Colonic diverticular disease 4 Abdominal trauma 3 Abdominal malignancy 3 Perforated peptic ulcer 3 Pancreatitis 2 Ruptured AAA <1 Inflammatory bowel disease <1 Gastroenteritis <1 Mesenteric ischaemia <1 Causes of Non-Specific Abdominal Pain Viral infections Bacterial gastroenteritis Worm infestations Irritable bowel syndrome Gynaecological causes Psychosomatic pain Abdominal wall pain Iatrogenic peripheral nerve injuries Hernia Myofascial pain syndrome Rib tip syndrome Nerve root pain Rectus sheath haematoma History of abdominal surgery 1809 (Christmas morning): Dr. Ephraim McDowell removed an ovarian tumor from Mrs. Crawford without anesthetic or antisepsis: "Having never seen so large a substance extracted, nor heard of an attempt, or success attending any operation such as this required, I gave to the unhappy woman…information of her dangerous situation…. The tumor…appeared full in view, but was so large we could not take it away entire…. We took out fifteen pounds of a dirty, gelatinous looking substance. After which we cut through the fallopian tube, and extracted the sac, which weighed seven pounds and one half…. In five days I visited her, and much to my astonishment found her making up her bed.„ McDowell E. Three cases of extirpation of diseased ovaria. Eclectic Repertory Anal Rev. 1817; 7:242-4. The risk of fatal infection was very high – the operation was bitterly criticized. 1879: Jules Émile Péan (1830-1898) opened the abdomen of a patient with cancer of the pylorus. The diseased section was cut out, the remainder was sewed to the duodenum. The patient died 5 days later. 1880: Ludwig Rydyger: same procedure but it had been planned in advance; the patient died within 12 hrs of "exhaustion." 1881: Christian Albert Theodor Billroth (1829-1894): successful operation (the patient died 4 months later due to the propagation of the tumor). Two other, deadly operations: Billroth was stoned on the streets of Vienna. 1885: Billroth II (pylorus cc): successful operations Technical background of abdominal incisions. Incisions – basic principles Abdominal incisions are based on anatomical principles They must allow adequate assess to the abdomen They should be capable of being extended if required Ideally muscle fibres should be split rather than cut Nerves should not be divided The rectus muscle has a segmental nerve supply. It can be cut transversally without weakening a denervated segment Above the umbilicus tendineus intersections prevent retraction of the muscle Site, type, etc. of laparotomy is depending on: The disease process, Body habitus, Operative exposure, Simplicity, Previous scars, Cosmetic factors, The need for quick entry into the abdominal cavity Recap: relevant anatomy of the abdominal wall Layers to be cut: Skin Superficial fascia (Camper’s), Deep fascia (Scarpa’s) Anterior rectus sheath, Rectus abdominis muscle Posterior rectus sheath down to arcuate line Transversal fascia Extraperitoneal connective tissue Peritoneum Recap: vessels of the anterior abdominal wall The superficial vasculature originates from branches of the femoral artery and includes the superficial epigastric, the superficial circumflex, and the superficial external pudendal arteries. These vessels course through the tissues anterior to the rectus sheath. The deep vasculature = from the external iliac and the internal thoracic artery. Inferior epigastric a. originates from the external iliac and courses posterior to the lateral 1/3 of the rectus m. Deep circumflex a., branch of the external iliac, courses cephalad lateral to the inferior epigastric artery. The superior epigastric a. (branch of the internal thoracic a.) forms anastomosis with the inferior epigastric. The internal thoracic artery is the source of the musculophrenic artery - anastomosis with deep circumflex. Recap: important things about nerves • Lateral to the midline, a transverse incision is least likely to injure nerves • The iliohypogastric (ih) and ilioinguinal (ii)nerves are sensory: – ih injury loss of sensation in skin over mons – ii injury loss of sensation in labia majora • Both IH and II supply the lower fibers of the internal oblique and transversus, if divided, denervate these fibers and can increase risk of inguinal hernia Recap: principles of healing • Patient factors that negatively affect wound healing: – Diabetes, obesity – Poor nutrition – Prior radiation or chemotherapy – Age – Alcohol – Ascites, malignancy – Immunosuppression – Coughing, wretching • Hospital factors that negatively affect wound healing: – Long operations – Long time in hospital pre-op – Drains through incision – Shaving prior to surgery – Type of suture – Closure technique Prevention of wound complications • Same scalpel can not be used for skin and deep incisions (?) • Avoid deep subcutaneous sutures, but may use 4.0 Dexxon subcutaneously to decrease tension on the skin • Never use cat-gut on fascia or subcutaneously • Contaminated or dirty wounds: – delayed closure – staples with saline soaked gauze • Opening of a bacteria-containing organ: – – – – delayed closure irrigation of all layers monofilament, delayed: non-absorbable suture systemic antibiotics 30 min before operation or asap and repeat if prolonged case Surgical intervention: anesthesia • Method: general anesthesia • Equipment: typical monitors, respirator, warming blanket • Anesthesia will insert a nasogastric tube after intubation Surgical intervention: positioning • Position during procedure: supine with arms on armboards • Supplies and equipment: insertion of Foley catheter, application of electrodispersive pad • Special considerations: high-risk areas (for geriatric, pay particular attention to skin and joints). Surgical intervention: Skin prep • Method of hair removal: clipper or wet • Anatomic perimeters: traditional abdominal from nipple line across chest from table side to table side to mid-thigh • Solution options: Betadine (povidon-jodid) or alternate: Hibiclens (USA) Surgical intervention: draping/incision • Types, order of drapes: 4 towels, laparotomy T-sheet • Special considerations: – in case of exploration: usually midline. It gives best exposure to all segments of bowel (depends on location of lesion—could be paramedian or oblique, etc.) Surgical intervention: supplies • General: blades (3) # 10 and (1) # 15, electric unit pencil, suction tubing, hemostats (all sizes); staples (optional) • Specific – Suture: ample supply of free ties. Sizes 2-0 and 3-0 are most common. – Catheters and drains: may use Penrose drain for retraction Lecture C2. Incisions, exposure of intraabdominal organs 2. Appendectomy Major types of incisions Longitudinal Midline Supraumbilical (upper midline) Infraumbilical (lower midline) Right and left paramedian McEvedy (1950) preperitonal approach for inguinal and femoral hernia repair (McEvedy PG: Femoral hernia. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1950;7:484–496.) Oblique Kocher for cholecystectomy (sec. Theodor Kocher (1841-1917) 1909: Nobel prize for medicine and physiology, mainly for thyroid surgery) McBurney for appendectomy (Charles McBurney (1845–1913) in 1897 performed his first operation for appendicitis) Right and left inguinal Thoraco-abdominal Transverse Maylard Pfannenstiel Cherney Transverse muscle splitting Gable Lanz Midline incision Characteristics • The commonest approach to the abdomen • The following structures are divided: skin - linea alba - transversalis fascia extraperitoneal fat - peritoneum • The incision can be extended by cutting through or around the umbilicus • Above the umbilicus the falciform ligament should be avoided • The bladder can be accessed via an extraperitoneal approach through the space of Retzius • In case of previous operations go higher and open peritoneum where unlikely to be scarred • Ensure hemostasis of the above layers before entering the peritoneum Advantages • Excellent exposure to abdomen and pelvis • Easily extended • Rapid entry into abdominal cavity • Midline is least hemorrhagic incision • Easy to perform • Linea alba guide the midline Disadvantages • Scar may be wide and not beautiful • Possible increase in hernias and dehiscence with midline Paramedian incision Characteristics • Site: parallel to and approx. 3 cm from the midline • The following structures are divided: skin - anterior rectus sheath (m. rectus is retracted laterally) - posterior rectus sheath (above the arcuate line) - transversalis fascia - extraperitoneal fat - peritoneum • Closed in layers Advantages the rectus muscle is not divided (the incisions in the anterior and posterior rectus sheath are separated by muscle) has a lower incidence of incisional hernia Disadvantages takes longer to make and close may decrease risk of incisional hernia vs midline but strength of closure is equivalent increased risk of infection, intraop. bleeding, risk of nerve damage if placed beside a midline, can compromise blood supply in the middle restricted to need for excellent exposure on one side of abdomen/pelvis Transverse Incisions Advantages • best cosmetic results • 30x stronger than midline incisions • less painful than longitudinal incisions • less interference with respiration • No difference in dehiscence rate Disadvantages • more time consuming • more hemorrhagic • nerves sometimes divided • spaces opened and potential for hematomas • limited upper abdominal access Transverse incisions - Pfannenstiel • most wound security (in case of pelvic incisions), least exposure • usually 10-15 cm long • separates the perforating nerves and small vessels from ant. rectus → may weaken incision • if extended past the m. rectus can damage ih and ii nerves • may require subfascial drainage Transverse Incisions – Maylard • used for radical pelvic surgery • • • • • true transverse muscle cutting incision good pelvic exposure transverse incision 3-8 cm above symphysis ligation of inf. epigastric artery before dividing the rectus no need to include muscles in fascial closure Transverse Incisions – Cherney • like a Pfannenstiel incision but divides the m. rectus at the tendinous insertion to symphysis • excellent access to space of Retzius • re-attachment of muscle tendons to rectus sheath, not symphysis → avoid osteomyelitis Transverse Incisions – Lanz Characteristics Special incision, better cosmetic results than McBurney Main indication: exposure of appendix and coecum; mirror image (left iliac fossa) can be used for for left colon (not for rectum). Site: right iliac fossa. As compared to McBurney: transverse, more medial toward rectus, closer to iliac crest (spina iliaca anterior superior) Disadvantage Due to its transverse direction ih and ii nerves can be damaged, incidence of hernia is higher. Oblique incisions McBurney or gridiron – Uncomplicated appendectomy – Extraperitonal drainage of pelvic abscess – Sigmoid colostomy Rockey Davis (Elliot) – Alternative to McBurney – Extends to lateral border of rectus Extraperitonal incisions for staging J-shaped 3 cm medial to iliac crest Extraperitoneal removal of paraaortic nodes Can be left-sided also but right is easier “Sunrise” incision 6 cm above umbilicus Extraperitoneal removal of paraaortic nodes Allows immediate irradiations Closure of laparotomy Basic principles of closing fascia • As few knots as possible is best • Place suture far enough back from edges of the fascia to account for some necrosis (1 cm back – 1 cm apart) • Place even tension on the suture (appose, do not necrose) • Avoid incorporating fat or underlying tissue when possible (except in en mass closure) Fascia closure: Smead Jones technique • “far-far, near-near” • includes a “mass” far bite on each side followed by “near” fascia-only bite with next bite • theoretically allows good healing by removing tension with “far” bites and closing fascia with “near” ones • takes a lot of time Muscle - midline incisions (Ceydeli A et al.: Finding the best abdominal closure: an evidence-based review of the literature. Curr Surg.; 62(2):220-5, 2005.) • rectus m. should not be sutured together unless symptomatic diastasis • mass closure better than layered closure • #1 or #2 absorbable monofilament suture • paramedian: layered or mass closure Drain – drainage in laparotomy • “passive” vs “active” • passive drains must never be brought out of the incision for risk of infection • often used if wound is contaminated or if persistent oozing, or large potential space • controversial whether prophylactic drains are beneficial in clean wounds • closed suction may be beneficial in clean/contaminated cases – but mainly if no antibiotics are to be used Obese patients • “morbid” if >130% weight or BMI> 30 • any transverse incision should be far removed from moist warm pannicular folds • modified “obese patient” routine: – cleaning of umbilicus – pre-op shower – 5000-8000 U /12 h heparin starting 2 hr pre-op – sequential compressing stockings – clip prep of abdominal hair – careful prep, under pannus, too – pannus retracted caudal – running mass closure – drains placed above the fascia, removed after 72 hrs or with output < 50 ml/24 hrs – staples left for 2 weeks Dehiscence • Fascial dehiscence complicates 0.3% - 3% of all pelvic surgery • Mortality of evisceration: up to 35% – Superficial: skin down to fascia – Complete: if involves disruption of peritoneum – Evisceration: intestine protrudes through the wound Risk factors for complete dehiscence • Metabolic – Malnutrition – Poorly controlled diabetes – Corticosteroid use – Older age • Mechanical: – Obesity – Abdominal distention (incl. ascites re-accumulation) – Infection – Coughing Signs • Usually occurs 5-14 days post op (mean: approx. 8 days) • Warning sign: seepage of pink fluid from intact wound • Usually a tissue failure, not a suture failure (88% of eviscarations had tearing of fascia and knots intact) • Approximate, do not strangulate, or you will eviscerate! Repairing a dehiscence • Usually should be closed immediately • Always in operating room • If delay required (e.g. patient just had lunch) – replace bowels with sterile gloves and – soak with povidone–iodine lap pads – abdominal binder • Broad spectrum antibiotics • Removal of necrotic tissue, clots, old suture • Bacteriology, cultures from the abdomen • Irrigation with warm saline • Fascia: – If intact: Smead-Jones closure • Skin left open for secondary closure – If damaged: retention suture with #2 nylon or polypropylene • Suture: 2.5-3 cm from skin edges, passed through all layers, 2 cm apart to allow for edema • Leave for 3 weeks Irrigation • „The solution to pollution is dilution” • Irrigation with saline or water is beneficial to remove contamination • Irrigation with antiseptics, such as 1% povidon-iodide may be cytotoxic to fibroblasts • Iv or oral antibitics are probably better choice if there is a concern Laparotomy – GI operations - surgical conditions Mechanical lesion Large bowel obstruction Band/adhesion Malignancy Volvulus Intussussception Fecal Impaction Trauma Blunt / penetrating Inflammatory Diverticulosis/diverticulitis Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease Appendicitis Vascular Ischemic colitis Vascular occlusion/infarction Arterio-venous malformation Recap – history of appendectomy 1521: Jacopo Berengario da Capri (1460-1530): appendix as anatomical structure 1600- Vidus Vidius’s book of anatomy (Guido Guidi, 1500-1569): appendix. cc. 1710: Philippe Verheyen (1648-1710): appendix vermiformis 1800: „Lower abdominal pain" 1812: Connection between peritonitis and necrotic appendix (Parkinson). 1824: Connection between periappendicular innflammation and necrotic appendix (LouyerVillermay). 1827: Connection between periappendicular abscess and appendix (Mellier). 1848: Surgical drainage of periappendicular abscess (Hancock). 1856: Surgical drainage of periappendicular abscess No.2. (Levis). 1874: Surgical drainage of periappendicular abscess No. 3. (Parker). 1882: Death of Leon Gambetta, Prime Minister of France. Autopsy: periappendicular abscess. 1886: Reginald H. Fitz (pathologist): „lower abdominal pain„ = "appendicitis”; proposes surgery in case of signs and symptoms. 1887 April 27: George Thomas Morton: first successful human appendectomy, removal of a perforated appendix. 1889: John Murphy’s series of 100 successful appendectomies. Relevant anatomy • The appendix does not elongate as rapidly as the rest of the colon: thus forming a wormlike structure. Average length: 10 cm (2-20) • Inner circular, outer longitudinal (continuation of the taeniae coli) muscle layers. Submucosal lymphoid follicles enlarge (peak 12-20 years) and then decrease: correlating with the incidence of appendicitis. • Blood supply: appendicular artery (branch of the ileocolic artery). • The base is at a constant location, whereas the position of the tip of the appendix varies; 65%: retrocecal position; 30%: at the brim or in the true pelvis; 5%: extraperitoneal, behind the cecum, ascending colon, or distal ileum. • The location of the tip of the appendix determines early signs and symptoms. Open appendectomy Incision • RLQ (right-lower quadrant) incision over the McBurney point (2/3 of the distance between the umbilicus and the anterior superior iliac spine) • The subcutaneous tissue and Scarpa fascia are dissected until the external oblique aponeurosis is identified. This aponeurosis is divided sharply along the direction of its fibers. • A muscle-splitting technique is then used to gain access to the peritoneum. Once the peritoneum is entered, any purulent fluid should be cultured. Delivering the appendix • Retractors are placed into the peritoneum, and the cecum is identified and partially exteriorized using a moist gauze pad. The taenia coli is followed to the point where it converges with the other taenia, leading to the base of the appendix. • The appendix is brought into the field of vision. Gentle manipulation may be required to bluntly dissect any inflammatory adhesions. Division of the mesoappendix and ligation of the appendix Once the appendix is exteriorized, the mesoappendix is divided between clamps, divided, and ligated. Removal • The base of the appendix is clamped then tied off with a 0 suture. • The appendix is amputated and passed off the field as a specimen. • The mucosa of the appendiceal stump may be cauterized to avoid future mucus production. • Purse-string suture is used to invert the appendiceal stump (some authors state that it is not necessary). „Z” suture of the serosa. • The cecum and appendiceal stump are then placed back into the abdomen. • If free perforation is encountered, thorough irrigation of the abdomen with warm saline solution and drainage of obvious cavity, well-developed abscesses is required. Closure of the incision • The peritoneum is identified, and closed with a continuous 2 or 3-0 suture. The inferior oblique muscles are re-approximated with a figure-of-eight interrupted absorbable 0 to 3-0 suture, and the external oblique fascia is closed with interrupted 20 PG suture. • The skin may be closed with interrupted 2/0 monofilament non-absorbable suture, staples or subcutaneous sutures can be used too. Use of staples is recommended if the appendix was perforated and skin closure is to be performed. • The skin should be left open in cases of perforated appendicitis, with delayed primary closure performed on postoperative day 4 or 5.