Patient Selection for Uterine Fibroid Embolization

advertisement

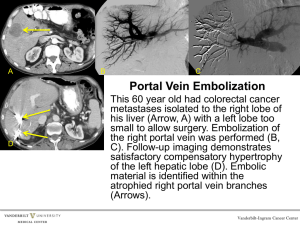

681445102 Uterine Fibroid Embolization: Is it Universally Suitable? J. Spies Associate Professor of Interventional Radiology, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, U.S.A. Introduction The growing acceptance of uterine artery embolization (UAE) as a treatment for leiomyomata has led to its use in many centers across the country and the world. It has created considerable interest among women and the lay press. Gynecologists are becoming aware of the procedure and, in many centers, are regularly referring patients for evaluation and treatment. With several years of experience with this treatment around the world, sufficient data is now available to allow some perspective of the outcome from this procedure. In this brief overview, we will touch on the success of uterine embolization and then discuss the failures: why they occur and how they may be avoided. We will conclude with a detailed discussion of the criteria that are used in patient selection. Symptomatic Outcome Since 1998, 10 case series of 49 patients or larger have been published (excluding duplicate reports) (1-10). These published results indicate that embolization is effective in improving symptoms in the large majority of patients. Between 81 and 94% of patients have improvement in their menorrhagia. For the bulk-related symptoms caused by fibroids, which include pelvic pain, pressure and bloating, as well as urinary frequency, symptoms are improved in 64-96% of patients. The variability in outcome relates in part 1 681445102 to the means of assessment of outcome. In most of these series, the symptom follow-up was obtained via questionnaire, with patients rating their symptom change. Conversely, about 10 to 15% of patients are not improved after uterine embolization. A systematic analysis of failure has never been published to our knowledge. However, one can theorize the reasons that patients may fail to have symptomatic improvement. First, misdiagnosis of the cause of a patient’s symptoms may occur. Once fibroids are diagnosed, there is an assumption that all symptoms are related to the fibroids. Careful evaluation before any fibroid intervention should reduce this occurrence. From a technical perspective, the procedure may fail for 3 reasons. First, there may be failure of catheterization and thus non-embolization of one side of the uterus. There may also be reperfusion of the fibroids after apparently successful embolization of the blood supply. This may result from redistribution of the particles after final embolization images are obtained. Finally, parasitization of vascular supply from other sources may result in failure. The most common source is the ovarian artery, which may supply the fibroids in up to 5% of cases. For any of these reasons the fibroids may fail to infarct and thus the symptoms may not improve. Complications are very infrequent after uterine embolization. In a recent scientific abstract detailing adverse events in 400 patients, complications occurred in 10%, the large majority of which were minor, requiring treatment with medications only (11). There was only 1 hysterectomy required for an adverse event, in this case bleeding associated with fibroid expulsion 4 months after treatment. There have been hysterectomies that have been required in less than 1% of patients (4, 10, 12) and 2 reported deaths, one from sepsis (13) and one from pulmonary embolus (14). Perhaps the 2 681445102 most common complication requiring gynecologic intervention is fibroid expulsion that occurs in 2.5 to 5% of patients (11, 15). This is one complication that may occur weeks or months after the procedure. Patient Selection As with all medical therapies, the effectiveness and safety of uterine embolization will be enhanced by the proper assessment and selection of patients prior to therapy. Not only does the diagnosis of fibroids need to be confirmed, but also the symptoms that the patient is having should correspond to the size and position of the fibroids. In addition, other likely causes of symptoms and even important asymptomatic pathology should be excluded. These efforts are greatly facilitated by a routine protocol for pre-procedure assessment. This presentation is intended to provide the basis for developing a preprocedure evaluation protocol for fibroid patients. Pre-Procedure Gynecologic Evaluation Every patient should be evaluated by a gynecologist prior to UAE, preferably within three months prior to therapy. This is not just to confirm the diagnosis of fibroids and to confirm that the symptoms the patient is experiencing are due to fibroids. A patient’s overall gynecologic health must be confirmed, including insuring that a Pap smear is negative. In those cases when atypical symptoms are present or the pattern of bleeding is unusual, additional gynecologic evaluation may be needed. For all these reasons, a cooperative relationship with gynecologists is important. For appropriate selection of patients for UAE and other fibroid therapies, it is important that both specialties contribute their skills. As most interventionalists will realize, some 3 681445102 patients are best treated by medical or surgical therapies and the relationship with gynecologists will be reciprocal. Pre-procedure Imaging It is important to confirm the diagnosis of fibroids with pre-procedure imaging, but also to assess the size and location of the fibroids. In particular, it is important to correlate the fibroid’s position with the symptoms that the patient is experiencing. The standard method of pre-procedure imaging is ultrasound, but we have routinely used MRI instead. We chose to use MRI for several reasons. First, it gives much superior anatomic detail of the location and size of the fibroids when compared to ultrasound. The measurements obtained are not as operator dependent as those obtained with ultrasound. Ultrasound often has difficulty penetrating through very large uteri and often the ovaries cannot be identified. In nearly all cases, we have been able to visualize the ovaries with MRI. The internal architecture of the fibroids is much more readily apparent with MRI and in particular it is possible to determine if a fibroid has already degenerated prior to treatment. With the use of contrast, the enhancement pattern of the fibroids and the surrounding uterus can easily be evaluated. If we determine that a fibroid is avascular before treatment, we will be concerned that embolization will not help. Contrast use is particularly important on follow-up scans. On occasion, we will note that a patient’s fibroid may have only decreased in volume 10 or 20% three months post treatment. With MRI, one can readily determine if the fibroid has successfully infarcted or whether there is persistent viable tissue. This has helped us sort out those that were successfully treated 4 681445102 from those that have failed as a result of aberrant or parasitized blood supply or inadequate embolization. Another key reason for using MRI is it is more accurate in diagnosing adenomyosis. We have discovered several patients that had pure adenomyosis that had had previous ultrasound diagnoses of fibroids. At this time it is not known if adenomyosis can be treated with embolization with the same result as fibroids and therefore we believe accurate diagnosis is important. MRI protocol includes breathhold orthogonal single shot fast spin echo (Haste) and T1 weighted spoiled gradient echo sequences obtained at 30 seconds, 60 second, and 90 seconds after the dynamic infusion of intravenous gadolinium. We believe follow-up imaging after embolization should be obtained at least once in each patient. This is important to ensure that the fibroid is infarcted and that it is shrinking. If there is continued growth of the fibroid, it may mean that the “fibroid” was in fact a leiomyosarcoma, which will obviously require surgery. Patient Selection Who to treat and who not to treat After the work-up is completed, the decision remains: Should this patient be offered UAE or should she have a different therapy? The first decision is whether the patient’s symptoms warrant therapy. Presuming that the symptoms are due to fibroids, are they severe enough to affect the daily life and activities of the patient? Many patients will present with a diagnosis of fibroids and a recommendation by a gynecologist to have a hysterectomy. This recommendation may be given even in the absence of symptoms. The patient may then seek an alternative therapy, 5 681445102 such as UAE. Many of these patients may only need reassurance that no therapy is necessary, or at least not currently. The only circumstances when therapy is needed in asymptomatic patients are those with hydronephrosis, a uterine mass that appears to represent a sarcoma, and in patients with fertility problems that are directly referable to the fibroids. In this last group, myomectomy is currently the procedure of choice. The same logic can be used when the symptoms are mild. For heavy bleeding that is only mildly increased over normal, medical therapy can be recommended when the bleeding is not severe. These therapies include NSAIDS, birth control pills, and progesterone agents. Bulk-related therapies do not respond well to medical therapies and generally UAE or surgery are the only practical therapies. However, the patient should be reassured that treatment can wait for the symptoms to become more severe before treatment is undertaken. It should be remembered that our results are measured in symptom improvement, and minimal symptoms will result in minimal benefit. Given sufficient symptoms to treat, most patients are candidates for UAE. The patients that might be better served by other therapies include those with pedunculated submucosal fibroids, pedunculated dominant serosal fibroids, and massively enlarged uteri. Pedunculated submucosal fibroids may be amenable to hysteroscopic resection. This is a simple outpatient procedure with excellent results in experienced hands. However, the procedure usually requires pre-treatment with Lupron for three months to devascularize the fibroid and reduce its size. Also, large (>4cm) fibroids may not be easily resectable. However, we refer all patients with significant intra-cavitary fibroids for a gynecologic second opinion. UAE certainly works in this group of fibroids and we 6 681445102 have treated many patients in this group. However, these are in circumstances in which hysteroscopic resection has failed or in which the patient has refused. Large pedunculated subserosal fibroids that are the dominant or sole fibroid are usually referred for myomectomy. UAE may work, but there have been concerns that these may have parasitized blood supply from other pelvic vessels. There has also been at least one case in France and perhaps others in which a pedunculated subserosal fibroid sloughed into the abdominal cavity and became infected or caused significant intra-pelvic adhesions. These fibroids are also easily accessible by surgery and until more data on the behavior of this group of fibroids after UAE, myomectomy may be preferred. Finally, we usually recommend that patients with a massively enlarged uterus (greater than 22 to 24 cm in length) have a hysterectomy. This is based on our experience that very large uteri appear to shrink more slowly and even with a 50% reduction in volume, a very large uterus will remain. We have had several patients that were disappointed when their uterus did not return to more normal size. There also have been some reports that some patients with massive uterus have had persistent pain for months after embolization and there is some concern that very large uteri may be more likely to become infected. While there is no published data in this regard, we have made the admittedly arbitrary judgment to refer this group for surgery. It is also important to be certain that the symptoms the patient has are related to fibroids. Fibroids do not cause heavy menstrual bleeding unless they are distorting the endometrial cavity or the adjacent myometrium. Thus, smaller intramural fibroids without this distortion may not be the cause of abnormal bleeding. Other causes to consider include endometrial polyp, endometrial hyperplasia, adenomyosis, and 7 681445102 dysfunctional uterine bleeding. We have seen many patients with trivial fibroids and abnormal bleeding who have been referred for uterine embolization and it is important to triage them appropriately to avoid a treatment failure due to misdiagnosis. Similarly, the bulk symptoms that patients have are generally in direct relation to their size and location. Again, very small fibroids without much bladder compression are unlikely to be the cause of urinary symptoms. All these recommendations are general in nature and each patient must be evaluated individually. For this reason we again recommend that a cooperative relationship be created with referring gynecologists. With appropriate collaboration, patients will obtain the best therapy and the best outcome. Summary UAE is a great advance in the treatment of uterine fibroids, but as in all medical or surgical therapies, it can only be effective when patients are properly evaluated and the therapy offered is appropriate for that patient. In this presentation, we focused on issues that are important in selecting patients for UAE and thus ensuring the best outcome. With a collaborative relationship between gynecologists and interventional radiologists, the patient will be offered the best choice of therapies and will therefore be best served. References 1. Andersen PE, Lund N, Justesen P, Munk T, Elle B, Floridon C. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids: Initial success and short-term results. Acta Radiol 2001;42(2):234-8. 2. Brunereau L, Herbreteau D, Gallas S, Cottier J-P, Lebrun J-L, Tranquart F, et al. Uterine artery embolization in the primary treatment of uterine leiomyomas: technical 8 681445102 features and prospective follow-up with clinical and sonographic examination in 58 patients. AJR 2000;175:1267-1272. 3. Goodwin S, McLucas B, Lee M, Chen G, Perrella R, Vedantham S, et al. Uterine artery embolization for the treatment of uterine leiomyomata: midterm results. JVIR 1999;10:1159-1165. 4. Hutchins F, Worthington-Kirsch R, Berkowitz R. Selective uterine artery embolization as primary treatment for symptomatic leiomyomata uteri. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1999;6:279-284. 5. McLucas B, Adler L, Perella R. Uterine Fibroid Embolization: Nonsurgical treatment for symptomatic fibroids. J Am Coll Surg 2001;192:95-105. 6. Pelage J, LeDref O, Soyer P, Kardache M, Dahan H, Abitol M, et al. Fibroid- related menorrhagia: treatment with superselective embolization of the uterine arteries and midterm follow-up. Radiology 2000;215:428-431. 7. Ravina J, Ciraru-Vigneron N, Aymard A, Ferrand J, Merland J. Uterine artery embolisation for fibroid disease: results of a 6 year study. Min Invas Ther & Allied Technol 1999;8:441-447. 8. Siskin G, Stainken B, Dowling K, Meo P, Ahn J, Dolen E. Outpatient uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids: experience in 49 patients. JVIR 2000;11:305-311. 9. Spies J, Ascher SA, Roth AR, Kim J, Levy EB, J. G-J. Uterine Artery Embolization for Leiomyomata. Obstet and Gynec 2001;98:29-34. 10. Walker W. Uterine Embolization for leiomyomata: midterm results. In: Society of Minimally Invasive Therapy; 1999; Boston, MA; 1999. 9 681445102 11. Spector A, Spies J, Roth A, Baker C, Mauro L. Complications after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2002;13:S65. 12. Worthington-Kirsch R, Popky G, Hutchins F. Uterine arterial embolization for the management of leiomyomas: quality-of-life assessment and clinical response. Radiology 1998;208:625-629. 13. Vashisht A, Studd J, Carey A, Burn P. Fatal septicaemia after fibroid embolisation. Lancet 1999;354(9175):307-308. 14. Lanocita R, Frigerio L, Patelli G, Di Tolla G, Preafico C. A fatal complication of percutaneous transcatheter embolization for treatment of uterine fibroids (abstract). In: SMIT/CIMIT 11th Annual Scientific Meeting; 1999; Boston; 1999. 15. Berkowitz R, Hutchins F, Worthington-Kirsch R. Vaginal expulsion of submucosal fibroids after uterine artery embolization: a report of three cases. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1999;44:373-376. 10