SCHOOL EXCELLENCE INITIATIVE teaching paperB

advertisement

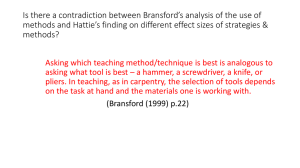

SCHOOL EXCELLENCE INITIATIVE Teachers: the key to student success The research evidence The Schools Excellence Initiative 2004 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 2 The research context .................................................................................................. 2 What the research tells us .............................................................................................. 3 Cognition: how people learn .................................................................................. 3 The impact of teaching on student outcomes ......................................................... 4 Inclusivity .............................................................................................................. 6 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... 8 Bibliography .................................................................................................................. 9 “What teachers know, do, expect and value has a significant influence on the nature, extent and rate of student learning. The powerful phrase ‘teachers make the difference’ captures the key role that professional educators play in shaping the lives and futures of their students.” (National Statement from the Teaching Profession on Teacher Standards, Quality and Professionalism, May 2003) Introduction The School Excellence Initiative is the overarching framework for achieving high standards in student learning, innovation and best practice in ACT Government schools. The concept of school excellence has the fundamental assumption that effective teaching is critical to student learning and that the degree of teacher expertise impacts on the outcomes of their students. Providing learning environments where every student is both supported and challenged is central to the ACT Government Schools Plans, Within Reach of Us All. The purpose of this paper is to support school excellence by summarising some key research on pedagogy and the characteristics of excellent teaching. It is a supplementary paper to the Discussion Paper Teachers: the key to student success, which provides a framework for professional dialogue and teacher learning across all schools in the ACT. The research context Over the past few years there has been a renewed focus locally, nationally and internationally on issues of pedagogy. All Australian governments are committed to supporting quality teaching. Reports from inquiries such as Quality Matters (the 2001 NSW Review into teacher education), The New Basics (Education Queensland, 2000) and Australia’s Teachers: Australia’s Future – Advancing Innovation, Science, Technology and Mathematics (the 2003 Commonwealth Review into teaching and teacher education) have affirmed that effective teaching is more important than any other factor in raising student achievement. The Australian Council of Deans of Education have issued a significant report The Role of the Teacher: Coming of Age (2003). All Australian Ministers have agreed to a National Framework for Professional Standards for Teaching (2003) which builds on work on teacher standards by teacher professional associations in English, Mathematics and Science. The Curriculum Renewal Evaluation Report, Every Chance to Learn, suggests that “the purpose of developing pedagogy is to improve student learning by selecting the most powerful teaching strategies for a specified learning outcome and to support different learners to achieve that outcome. The argument is not that one teaching strategy is always better than another, but rather that the strategies used need to be effective for the planned learning and for the learners. In a sense, it is about knowing how to choose the right tools for the job. Successful teachers establish effective relationships with their students, engage them in the learning and skilfully select the right strategies to ensure they achieve the desired outcomes.” (ACT Government, 2003:49) -2- What the research tells us Three key areas of research that impact on our understanding of pedagogy are: research into cognition, particularly the work of Bransford, Brown and Cocking research into the impact of teaching on student outcomes and on the dimensions of excellent teaching, particularly the work of Hattie and Martin research into supportive learning environments and ways of meeting the learning needs of students from diverse backgrounds and with differing learning styles, including the work of Grasha, Gardner, Vygotsky and Munns. Cognition: how people learn “If teaching is conceived as constructing a bridge between the subject matter and the student, learner-centered teachers keep a constant eye on both ends of the bridge.” (Bransford et al, 1999:136) Research into ‘the science of learning’ has provided new understandings about the way the human brain works and how students develop competence in an area of learning. Bransford, Brown and Cocking (1999) draw together this research and draw out three key implications for teaching. These are the need to: draw out and work with understandings that students bring with them develop students’ deep understanding and support their capacities to organise, retrieve and apply knowledge actively promote the development of students’ metacognitive skills. Draw out and work with understandings that students bring with them Research indicates that the most important aspect of learner-centred teaching is building on the students’ prior knowledge and connecting to students’ experiences. Students use their current level of learning to discover, construct and incorporate new knowledge, skills and understanding. “Teachers must actively inquire into students’ thinking by creating classroom activities and conditions under which student thinking can be revealed. Students’ initial understandings can then provide the foundation on which more formal understanding of the subject matter is built.” (ACT Government, 2004) This implies too that teachers need to identify pre-existing student preconceptions or misconceptions that make learning more difficult so that they can challenge these and lead students to new understandings. Develop students’ deep understanding and support their capacities to organise, retrieve and apply knowledge Research into brain function, and particularly into the way long-term memory works, shows that effective learning occurs when fewer topics are covered but at a greater depth. “Curricula that are a ‘mile wide and an inch deep’ run the risk of developing disconnected rather than connected knowledge.” (Bransford, Brown and Cocking, 1999: 5) -3- It is important for teachers to develop a sound basis of factual knowledge, and help students build conceptual frameworks that facilitate knowledge retrieval and application. Students need to be given many opportunities to practise what is learnt in a variety of contexts, to reinforce learning and support knowledge transfer. “Key concepts need to be explored in a variety of ways over a period of time in order for students to carry ideas forward and develop formal, transferable understandings to new ideas and areas of study.” (ACT Government, 2004: 51) Wiggins and McTighe (1998) suggest that understanding is developed when key ideas and skills are reiterated, explored and rethought. These key ideas and skills need to have value beyond the classroom and to be linked to real world issues, so that students are engaged in processes of inquiry and problem-solving that have some meaning to their own lives and to the issues facing contemporary society. Actively promote the development of students’ metacognitive skills “Metacognition refers to thinking about thinking in general, and reflecting on and regulating one’s own thinking and learning in particular. It is a kind of internal dialogue in which the learner monitors his or her own developing skills, understanding of concepts and mental approaches to the learning as it occurs.” (ACT Government: 2004) Teachers need to help students develop strategies to better understand, monitor and improve their own learning. As these strategies differ across learning areas and subjects, students need to be 'let into the secrets' of the area of study. Teachers need to explicitly share with students the keys to understanding and using the knowledge structures, terminology, and processes of a subject discipline or learning area. (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001, referenced in ACT Board of Senior Secondary Studies, 2003) Making reflection and self-assessment an integral part of the learning process supports metacognition and improves student learning. Metacognitive strategies also help students transfer learning from one context to another. “When students consciously develop ways of organising knowledge and learn to apply that knowledge to new issues and new problems, they are reinforcing generic capabilities. These are the capabilities they will need to maintain learning throughout their lives, within and beyond the workplace.” (ACT Board of Senior Secondary Studies, 2003) The impact of teaching on student outcomes “The quality of teaching is by far the most important influence on cognitive, affective and behavioural outcomes of schooling, regardless of a student’s gender or background.” (Australian Council for Educational Research, October 2003) In the 1960s and 70s, research suggested that family and socio-cultural background had the greatest influence on a child’s achievement and that schools could do little to ameliorate significant disadvantage (Coleman, 1966, and Jenks, 1972, referenced in Darling-Hammond, 2000). The whole school reform movement (characterised by the work of Newmann and the Coalition of Essential Schools in the United States and in Australia by the National Schools Network) countered this pessimistic view. Research supporting whole school improvement and the effectiveness of ‘learning -4- organisations’ suggested that student outcomes were significantly enhanced if they attended schools that had strong leadership and an effective learning culture. More recent research has focussed on the differences between whole school effects and within-school effects on student learning outcomes. In his analysis of research related to the educational outcomes of boys, Martin (2002) indicated that the teacher and class levels were “considered amongst the most critical points at which student outcomes can be improved.” He suggested that enhancing teacher effectiveness (for both boys and girls) involved assisting teachers in “dealing with diversity, promoting active learning, developing students’ higher order thinking, creating effective learning zones, promoting mastery and success, providing effective feedback to students, recognising and creating learning windows, developing good relationships with students, engaging in productive pedagogy and listening to and valuing student perspectives.” (Martin, 2002: 7) Some of the most compelling research about teacher effectiveness comes from the work of Hattie. He reviewed the literature on the difference between expert and experienced teachers and, working with researchers and teachers, identified dimensions of teaching that most influenced student learning outcomes. Hattie suggests that, while “what students bring to the table predicts achievement more than any other variable (about 50%)” teachers are by far the most profound influence on student achievement within schools (30%, with school, principal and peer effects each less than 10%). Hattie comments that “we need to ensure that this greatest influence is optimised to have powerful and sensationally positive effects on the learner.” (Hattie, 2003:1-3) From this research, Hattie identified three key elements of teacher expertise that had the most effect on student learning outcomes. These were: challenge to students deep representation of knowledge effective monitoring and feedback. Challenge to students Students learn best when teachers have high expectations. All students are best supported in reaching challenging goals when teachers have a deep knowledge of their subject or learning area, a detailed understanding of the outcomes they expect students to achieve. when they select teaching strategies that build on students’ prior knowledge and provide structure and sequence for learning and when they use assessment tasks that expect students to go beyond knowledge recall and simple practical tasks. Such teachers believe that all students need to be ‘stretched’ as well as supported and make those beliefs explicit to students. "Believing that abilities are developed through effort is most beneficial to the learner, and teachers and others should cultivate that belief." (Graham & Weiner, 1996, referenced in US National Academy of Sciences, 2002: Chapter 6: 7). Deep representation of knowledge Hattie reaffirms the Bransford research about the importance of deep rather than surface learning. “Surface learning is more about the content (knowing the ideas and doing what is needed to gain a passing grade), and deep learning more about -5- understanding (relating and extending ideas, and an intention to understand and impose meaning).” (Hattie, 2003:9) The research evidence also demonstrates the importance of ‘pedagogical content knowledge’ (the application of general pedagogy to a subject or learning area). It contradicts the view that ‘a good teacher can teach anything’. Outstanding teachers have a strong grasp of learning theory and general pedagogical principles but a distinguishing feature is their expert application of such principles to the particularities of their subject or learning area. “There is a dynamic interaction between teachers' knowledge of their discipline and their knowledge of pedagogy.” (Bransford, Brown & Cocking, 1999, quoted in Alton Lee, 2003:10) A high level of pedagogical content knowledge enables teachers to draw on their deep knowledge, to improvise, to make connections to other areas of learning and to current local and global issues and to constantly challenge and extend student learning. Teachers’ deep knowledge helps build the deep knowledge of their students. This research supports a co-constructivist model of learning and teaching. Students do not construct their knowledge and skills in isolation from the teaching and learning context. Learning is a partnership between students and their teachers, who should not resile from their responsibility for developing and extending their students’ capacities. Effective monitoring and feedback Hattie’s research supports a weight of evidence about the importance of assessment for learning. The UK based Assessment Reform Group (2002) defines assessment for learning as “the process of seeking and interpreting evidence for use by learners and their teachers to decide where the learners are in their learning, where they need to go and how best to get there.” Assessment for learning needs to be aligned with assessment of learning, for the purposes of grading and reporting. Sound assessment and reporting practices are based on a knowledge of how people learn and are integral to the learning process. They support students’ understanding of how they learn and how they might improve their learning. Expert teachers align their curriculum goals and their assessment practice and make the purposes and criteria for assessment clear to students. They use tasks that promote inquiry, deep knowledge, higher order thinking and demonstration of knowledge and skills in authentic contexts. Inclusivity “Inclusivity in education starts with the recognition of our diversity. It is treating students as individuals rather than as a homogeneous group. It is about involving all students in classroom practices by valuing their uniqueness and what they bring to the classroom. It is about valuing their interests, experiences, abilities, insights, needs, cultural and ethnic backgrounds, learning styles and intelligences.” (ACT Department of Education, Youth and Family Services, 2002:1) ‘Learner-centred teaching’ is a commonly used term. Bransford uses the term to refer to environments that pay careful attention to the knowledge, skills, attitudes and -6- beliefs that learners bring to the educational setting. This term includes teaching practices that have been called ‘culturally responsive’, ‘culturally appropriate’, ‘culturally compatible’ and ‘culturally relevant’.” (Bransford., Brown & Cocking, 2000: 133-134) Bransford draws on research to demonstrate the importance of teachers recognising and valuing student differences in cultural background and in learning style and the importance of building a supportive classroom environment. There are four aspects to consider in addressing diversity and inclusivity: individual differences and starting points socio-cultural effects the limitations of a ‘supportive’ approach the need to develop a ‘community of learners’ Individual differences The research of Gardner and Grasha suggests that intelligence has many different dimensions (Gardner, 1993; Grasha, 1996). Students learn in different ways and at different rates. There are many ways in which they can demonstrate what they know and what they can do. Grasha has defined learning styles as "personal qualities that influence a student's ability to acquire information, to interact with peers and the teacher, and otherwise participate in learning experiences" (Grasha, 1996: 41) The implication of this research is that teachers need to employ a repertoire of teaching strategies to allow for individual differences, including the use of information and communication technologies. They also need to give students choices within the framework of agreed curriculum requirements and use assessment tools that are fair and equitable. Socio-cultural effects Individual learning and the development of public bodies of knowledge (including the development of curriculum ‘subjects’) are both situated in social, historical and cultural contexts. A socio-cultural model of learning recognises that knowledge is not fixed and that understanding is developed through the interaction between individuals, their culture(s) and the learning at hand. Adopting a socio-cultural model necessitates the fostering of critical literacies so that students can better understand how meaning is constructed and influenced by its context and purpose. The socio-cultural model also requires teachers to examine critically their own beliefs and assumptions. More students will experience success where their cultural background, including language, is both respected and drawn upon in their schooling. For example, an analysis of Australia’s Indigenous Education Strategic Initiatives Program (IESIP) identified cultural recognition, acknowledgement and support as critical factors in ‘what works’ for indigenous students. (McRae et al, 2000) Such recognition relates closely to the key Bransford research finding that building on students’ prior knowledge and experience is the most critical factor for educational success. The limitations of a ‘supportive’ approach Intentions to provide an inclusive curriculum often falter when they come up against day-to-day realities of classroom management. Munns has conducted research in -7- classrooms in low socio-economic areas, with large indigenous and culturally diverse student populations, which point up the limitations of a ‘supportive’ approach. Munns uses the metaphor of school as a cubby-house. Children, secure in their cubbyhouse, can play and pretend. However, this is an illusion. In the end a cubbyhouse offers no protection from or preparation for the world.” Cultural sensitivity and supportive relationships are important but they are insufficient if students are not engaged in challenging tasks and cannot achieve educational outcomes that will give them power over their future lives. “The irony is that the socially just intentions of the school over a prolonged period of time resulted in a curriculum that reinforced the educational disadvantage of its most needy students.” (Munns, date unknown:1) A community of learners The research of Vygotsky has been particularly influential in illustrating how social interaction plays a fundamental role in the development of cognition. Vygotsky suggests that every function in a child’s development occurs twice. Learning occurs first on a social level, between people, and only then on an individual level, when the child internalizes a concept. A major aspect of Vygotsky’s theory is what he terms ‘the zone of proximal development’. By this he means that students need adult guidance, peer collaboration and plenty of practice in order to fully develop their understandings and skills. (‘Vygotsky, 1978) “… the question confronting educators today is not whether group learning should happen: rather it is a matter of identifying the ways that educators can support and deepen the quality of learning that can occur whenever individuals are together in a group. Learning in a group fosters a kind of emotional and intellectual learning and understanding that is qualitatively different from that which results in individuals working alone.” (Krechevsky & Stork, 2000) Learning is strengthened in classroom communities where students are engaged in substantive conversations and collaborative tasks and where students feel connected to the school community, the local community and the wider world. Bransford emphasises the importance of ‘learner-centred, knowledge-centred and community centred’ teaching. His notion of community centred teaching encompasses is based on an understanding of learning as a social activity and learners as social beings. He stresses the importance of learning communities with common purposes and opportunities for collaborative effort. These communities connect classroom learning to the local community and the world of work. They connect classroom learning with the wider world through engagement in significant local and global issues and through interactions with experts and learners across the world. Finally, Bransford emphasises that these classroom communities are supported (or inhibited) by whole school cultures and the extent to which teachers themselves feel part of professional learning communities Conclusion Learning and teaching are two sides of the same coin. The research evidence about how people learn best, about the dimensions of teaching that make the most difference to student outcomes and about the impact of students’ backgrounds and learning styles gives teachers a solid theoretical base from which to work. Insights gained from this research can help them reflect on their practice, share ideas with colleagues, shape -8- their own professional learning and – most importantly – improve learning experiences and outcomes for all their students. Bibliography ACT Board of Senior Secondary Studies 2003, Closing the Loop or Expanding the Circle: curriculum and assessment in ACT Senior Secondary Education, ACACA Conference Papers http://www.decs.act.gov.au/bsss/TeachingAndLearning/ACACA2003Paper.pdf ACT Department of Education, Youth and Family Services 2002, The Inclusivity Challenge, Canberra http://www.decs.act.gov.au/publicat/pdf/InclusivityReport.pdf ACT Government 2004, Every Chance to Learn: Curriculum Renewal Evaluation Report, Canberra http://activated.decs.act.gov.au/learning/curri_renewal.htm Alton-Lee, A, 2003, Quality Teaching for Diverse Students in Schooling: Best Evidence Synthesis, NZ Ministry of Education http://www.minedu.govt.nz/web/downloadable/dl8646_v1/quality-teaching-fordiverse-students-in-schoo.pdf Assessment Reform Group, Kings College London http://www.assessment-reform-group.org.uk/ Australian Council for Educational Research 2003, Quality Teaching Matters Most (media release) Australian Council of Deans of Education, 2003, The Role of the Teacher: Coming of Age, http://acde.edu.au/ Australian National Schools Network http://www.nsn.net.au Bransford, J, Brown, A & Cocking, R (eds) 1999, How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School, National Academy Press, Washington DC http://www.nap.edu/html/howpeople1/es.html Committee for the Review of Teaching and Teacher Education, 2003, Australia’s Teachers: Australia’s Future – Advancing Innovation, Science, Technology and Mathematics, Commonwealth of Australia http://www.dest.gov.au/schools/teachingreview/documents/Agenda_for_Action.pdf Darling-Hammond, L, 2000, Teacher Quality and Student Achievement: A Review of State Policy Evidence, Education Policy Analysis Archives Vol.8 No.1 http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v8n1 Gardner, H, 1993, Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice, Basic Books, NY Grasha, A, 1996, Teaching with Style, Alliance Publishers, Pittsburgh Hattie, J 1992, Measuring the effects of schooling, Australian Journal of Education Vol.36 Hattie, J, 2003, Teachers Make a Difference: What is the research evidence? ACER http://www.acer.edu.au/workshops/documents/Teachers_Make_a_Difference_Hattie. pdf Krechevsky, M & Stork, J, 2000, Challenging Educational Assumptions: lessons from an Italian-American collaboration, Cambridge Journal of Education, V30, No1 -9- Martin, A, 2003, Improving the Educational Outcomes of Boys, ACT Department of Education, Youth and Family Services http://www.decs.act.gov.au/publicat/pdf/ed_outcomes_boys.pdf McRae, D et al, 2000, What has worked (and will again): education and training for indigenous students, Australian Curriculum Studies Association & National Curriculum Services, Canberra Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs 2003, A National Framework for Professional Standards for Teaching Munns , G, date unknown, School as a Cubbyhouse: Tensions between Intent and Practice in Classroom Curriculum, University of Western Sydney National Academy of Sciences, Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, 2002, Learning and Understanding: Improving Advanced Study of Mathematics and Science in U.S. High Schools, National Academies Press http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10129.html National Statement from the Teaching Profession on Teacher Standards, Quality and Professionalism, 2003 http://www.austcolled.com.au/rand.php?id=206 Newmann (1996) Authentic Achievement: Restructuring Schools for intellectual quality, John Wiley Queensland Government, New Basics Project http://education.qld.gov.au/corporate/newbasics Ramsay, G, 2001, Quality Matters: Review of Teacher Education in NSW http://www.det.nsw.edu.au/teachrev/reports/ US National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, 1989, What Teachers Should Know and Be Able to Do www.nbpts.org/pdf/coreprops.pdf Vygotsky, L, 1978, Mind in Society, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA Wiggins, G & McTighe, J, 1998, Understanding by Design, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandra Note: all hyperlinks were active at the date of publication. -10-