The incidence of acute upper airway obstruction, and

advertisement

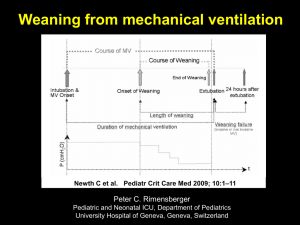

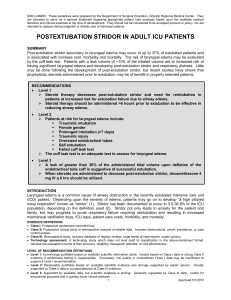

Guidelines for Evaluating the Airway Prior to Extubation in the ICU. Background The incidence of acute upper airway obstruction (UAO), and particularly stridor associated with laryngeal/subglottic edema following extubation is in the range of 2-16%.1 Approximately 1% of all extubated patients will require re-intubation specifically for stridor.2 Stirdor usually occurs within several minutes3 to 1 hour4 following extubation, but also has been reported to occur up to 8 hours.2 There are several risk factors associated with the development of acute UAO following extubation. Prominent risk factors include difficult/traumatic intubation,2 prolonged requirement for mechanical ventilation,2 prior incidence of traumatic self-extubation (i.e.: decannualtion with an inflated cuff),5 neurotrauma,6 female gender7 and obesity.8 Analysis of data from the SFGH quality-assurance weaning data base revealed that in 318 medical/surgical/trauma patients who required more than 48hrs of mechanical ventilation, and who underwent an initial trial of extubation, 9 patients required re-intubation for some form of upper airway obstruction within 96 hours (2.8%). Of these 9 cases, stridor was specifically cited in 3 cases (0.9%). The majority of patients (67%) required re-intubation within 24 hrs (mean time to re-intubation = 7.7 hrs). These patients were characterized as having a prolonged course of mechanical ventilation (mean = 6 days), having neurological disease/trauma (67%), female (56%) and older (mean age = 55 years). To reduce the probability of acute upper airway obstruction following extubation at SFGH, the following guidelines were created to standardize evaluation of the airway in order to improve identification of patients at increased risk. In addition, we have made recommendations for the approach to extubating patients at high-risk for acute upper airway obstruction, as well as therapeutic interventions that should be implemented when airway obstruction occurs. Identification of patients who are at high risk for developing acute upper airway obstruction following extubation can be analyzed according to 3 categories that address anatomic considerations, patient history and diagnostic tests. It is particularly important that the risk assessment include standard anatomic features likely to make re-intubation difficult in the event of acute UAO (Table 1). From this we have devised a tool to guide the clinician in utilizing the anesthesia service for an airway consultation (Table 2). Approved 3/1/2010; Revised 6/7/2012 Process for Airway Evaluation 1. Formal Airway History is gathered by members of the ICU team (physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists) upon admission to the ICU/at the time of intubation. The respiratory therapists will be primarily responsible for maintaining the airway history data for determination of the Extubation Risk Assessment Score (Appendix). 2. The primary document of interest is the record of intubation (anesthesia record, intubation record or emergency department record). In addition, as part of their report, respiratory care practitioners assisting with intubation should also document this information in their notes. The following information should be gathered: a. The degree of difficulty (defined as greater than 3 attempts (by an experienced anesthesiologist or emergency department physician (e.g.: failed attempts at intubation by an intern or subintern does not constitute a difficult intubation). b. The ease of manipulating the head into a sniff position c. The ability to visualize the vocal cords during intubation. d. Evidence of airway trauma as a result of intubation attempts (suctioning of blood from the hypopharynx or the trachea following intubation). 3. Mandated Cuff Leak Tests: Prior to initiating the SBT/DSI protocol, respiratory therapists will perform a cuff leak test in patients determined to have High Risk for developing acute UAO. These being: a. Presence > 3 “Moderate” Risk Factors b. Factors that carry a very significant for UAO (e.g. high cervical cord damage, upper airway infection, trauma or surgery, inhalation injury, etc (see Airway Risk Assessment Tool). c. Cuff leak test can be performed in non-high risk patients at the discretion of The ICU team. 4. Cuff Leak Test Methodology: In adult patients all cuff leak tests are performed using the volume-based measurement described by Miller.5 Analysis of SFGH qualityassurance data using the volume cuff leak test in over 160 patients reveals a positive predictive value of 55% and negative predictive value of 97% using the cutoff value of 110 mL. An appropriate volume-based measurement is not currently available for pediatric patients. Therefore alternative pressure-based reclusion-based tests may be used to evaluate airway patency in pediatric patients ventilated with small tidal volumes. 5. Anesthesia Consult required in high risk patients with a poor or absent cuff leak, in whom extubation is contemplated. A formal airway evaluation may be performed by an anesthesia resident or fellow in consultation with and anesthesia attending. Part of this evaluation may include direct laryngoscopic visualization to examine the vocal cords and upper airway. An anesthesia consult can be requested in any patient in whom the ICU team has airway concerns. 6. Interservice Communication: Extubation should be deferred temporarily in patients with direct visual evidence of airway edema. Decisions regarding subsequent airway management should be reached by consensus between the anesthesia, primary and critical care services. These decisions include whether to defer extubation pending re-evaluation at a further time point, short course [24 hr] of steroid therapy, extubation in the OR, or conversion to a tracheostomy). Approved 3/1/2010; Revised 6/7/2012 7. Patients who undergo steroid therapy should be re-evaluated either by cuff leak test and laryngoscopic exam after 24 hrs of steroid therapy and prior to an extubation trial. 8. Extubation of High Risk Patients: Extubation of high risk patients with an insufficient cuff leak test should be undertaken only at a time when an attending anesthesiologist or his/her designee is readily available to perform reintubation if necessary during the periextubation period (i.e.: 30 minutes). In addition, it should only occur at a time when a respiratory therapist can be readily available to initiate emergency therapy. Extubation of the patient with a diagnosis of “difficult airway” should only occur during the day. Easy availability of emergency respiratory therapy interventions (such as the ability to deliver aerosolized racemic epinephrine along with non-invasive ventilation or heliox) should be in place prior to extubation. Therapeutic Options: Prophylaxis In patients with direct visual evidence of airway edema, a short course [24 hr] of steroid therapy may reduce airway inflammation sufficiently to allow successful extubation. A recent metaanalysis9of 7 prospective, double-blinded, randomized-controlled trials concluded that corticosteroids administered prior to a planned extubation reduces the risk of post-extubation stridor and subsequent need for re-intubation. Steroids are more likely to be effective if administration begins at least 4 hours prior to extubation, and are most appropriate when targeted to patients at high-risk for developing postextubation. In the experimental studies reviewed, a variety of dosages were studied. Typically either 40 mg methylpredisolone or 5 mg dexamathasone is administered intravenously every six hours for 24 hours prior to extubation. A cuff leak test and or direct laryngoscopy should be repeated after steroid therapy and prior to the extubation trial. Treatments Patients who are at high-risk for developing acute UAO should have at least one the following therapies readily available at/near the bedside prior to extubation. All patients who develop signs of UAO should have therapy initiated rapidly. The following are guidelines for escalating therapy in response to acute UAO post-extubation. Stridor 1. All at-risk patients should receive prophylactic therapy using warm humidified oxygen immediately following extubation. This is the most basic treatment for mild stridor and should be instituted for at least 4-8 hrs following extubation. 2. For patients who develop post-extubation stridor, aerosolized racemic epinephrine (Vaponefrin, Micronefrin) should be administered. Approximately 2-5 mg (1-2 mL of a 2.25% solution) diluted in 3-5 mL of NS should be aerosolized preferably using a small-volume mask nebulizer. An additional treatment can be given at approximately 15 min. Onset of action is approximately 5 min with a duration of approximately 1 ½ to 3 hrs. Repeated use of racemic epinephrine should be done with caution as tachyphylaxis and paradoxical bronchospasm, therefore alternative adjunctive therapies should be considered (see #3). Racemic epinephrine should be used with caution in patients with hypertension or recent myocardial infarction. Approved 3/1/2010; Revised 6/7/2012 3. Patients in whom stridor worsens or does not improve after 1-2 aerosolized racemic epinephrine treatments should be re-intubated promptly. 4. If aerosolized racemic epinephrine appears to ameliorate stridor, consideration should be given to incorporating other therapy options such as non-invasive ventilation or heliox therapy. Heliox has been reported in the pediatric literature to reduce severe croup scores as effectively as racemic epinephrine.10 Therefore heliox can be used as a temporizing measure to limit dosing requirements with racemic epinephrine. Effective heliox therapy requires an FiO2 of < 0.40 and therefore is not an option in patients with severe hypoxemia. 5. At the discretion of the respiratory therapist/ ICU physician, aerosolized racemic epinephrine can be delivered in conjunction with either non-invasive ventilation or heliox depending upon the level of respiratory distress. 6. Close hemodynamic and Q-30 min to Q-1 hour arterial blood gas monitoring should be implemented in those patients who appear to be responding to therapy. Anatomic Obstruction ( poor upper airway muscle tone) The choice of interventions or order of escalation is left to the discretion of the clinician basedupon the severity of symptoms (e.g.: snoring vs. sustained complete obstruction of the upper airway) 1. Placement of nasal airway 2. Initiation of high-humidity, high-flow nasal oxygen therapy 3. Initiation of non-invasive ventilation either as nasal CPAP titrated between 5-15 cm H2O or BiPAP (inspiratory presures of 10-20 cm H2O with expiratory pressures of 5-10 cm H2O). Post-Obstructive Pulmonary Edema Following the relief of acute UAO, the development of post-obstructive pulmonary edema is a distinct possibility. Clinicians should be prepared to institute aggressive supportive therapy. The primary therapy for post-obstructive pulmonary edema is positive pressure ventilation (either invasive or non-invasive) with moderate-to high levels of PEEP (10-15 cm H2O) high FiO2, and lung-protective ventilation (VT 6-8 mL/kg). Ancillary therapies such as use of diuretics and/or aerosolized beta-agonists may accelerate the re-absorption of pulmonary edema and hasten recovery. Post-obstructive pulmonary edema, although sometimes dramatic, is a self-limiting phenomenon that generally resolves within 24 hours.11 Initial Quality Assurance Monitoring Plan A pilot monitoring project will be launched in both the MICU and SICU to evaluate all patients who either are intubated for > 48 hrs, or have an obvious risk factor for developing acute UAO (e.g.: morbid obesity, traumatic intubation, facial trauma, etc). The pilot project will assess the feasibility of the process and to detect deficiencies in the monitoring or treatment regimen, All completed ERAS worksheets will be collected and maintained by the critical care QA director and maintained in a database. Approved 3/1/2010; Revised 6/7/2012 References 1. Jaber S, Chanques G, Matecki S, et al. Post-extubation stridor in intensive care unit patients. Risk factors, evaluation and importance of the cuff-leak test. Intensive Care Med. 2003; 29:69-74. 2. Darmon JY, Rauss A, Dreyfuss D, et al. Evaluation of risk factors for laryngeal edema after tracheal extubation in adults and its prevention by dexamethasone: A placebocontrolled, double-blind multi-centered study. Anesthesiology 1992; 77(2): 245-251. 3. Wang C-L, Tsai Y-H, Huang C-C, et al. The role of the cuff leak test in predicting the effects of corticosteriod treatment on postextubation stridor. Chang Gung Med J. 2007; 30: 53-61. 4. Maury E, Guglielminotti J, Alzieu M, et al. How to identify patients with no risk for postextubation stridor? J Crit Care 2004; 19(1): 23-28. 5. Miller RL, Cole RP. Association between reduced cuff leak volume and postextubation stridor. Chest 1996; 110: 1035-1040 6. Sandhu RS, Pasquale MD, Miller K, et al. Measurement of endo tracheal tube cuff leak to predict postextubation stridor and need for reintubation. J Am Coll Surg. 2000; 190: 682-687. 7. Jaber S, Jung B, Chanques G, et al. Effects of steroids on reintubation and postextubation stridor in adults: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care 2009; 13:R49: 1-11. 8. Erginel S, Ucgun I, Yildrim H, et al. High body mass index and long duration of intubation increase post-extubation stridor in patients with mechanical ventilation. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005; 207: 125-132. 9. Jabir S, Jung B, Chanques G, Bonnet F, Marret E. Effects of steroids on reintubation and post-extubation stridor in adults: mata-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care 2009; 13: R49: 1-11. 10. Weber JE, Chudnofsky CR, Younger JG, et al. A randomized comparison of heliumoxygen mixture (heliox) and racemic epinephrine for the treatment of moderate to severe croup. Pediatrics 2001; 107(6): 1-4. 11. Kallet RH, Daniel BM, Gropper M, et al. Acute pulmonary edema following upper airway obstruction: case reports and brief review. Respir Care 1998; 43(6): 476-480. Approved 3/1/2010; Revised 6/7/2012 Table 1. Anatomic Features Associated with Difficult Translaryngeal Cannulation Short Neck Small Chin ↑ Neck Circumference Large Tongue Facial Hair ↑ Body Mass Index Facial/Neck Trauma Protruding Maxillary Incisors Table 2 Airway Risk-Assessment Tool (Modified Version) Risk Stratification High Risk: Moderate Risk: Intervention Leak Test Required Leak Test: Clinician’s Discretion Risk Factors 3 or More Moderate Risk Factors Traumatic or Difficult Intubation Documented trauma, or 4 attempts, or Fiberoptic scope required Inhalation Injury or Major Burns (> 30% TBS) Traumatic Extubation Upper Airway, Infection, Mass, Trauma or Surgery Morbid Obesity BMI > 35) Cervical Spine Fracture C1-C5 Neurologic Disease /Injury Anterior Spinal Surgery Mechanical Ventilation > 6 days (i.e: unplanned ETT removal with inflated cuff) (e.g.: prolonged prone position) Facial Trauma or Surgery Female *Anesthesia consult is indicated whenever an extubation trial is contemplated in a patient with High-Risk Factors AND a poor leak test (< 110 mL). The initial evaluation may be performed by an anesthesia resident in consultation with an anesthesia attending. Approved 3/1/2010; Revised 6/7/2012