Experience of Services as a Key Outcome in Amyotrophic Lateral

advertisement

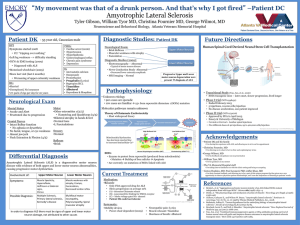

Experience of Services as a Key Outcome in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Care: The Case for a Better Understanding of Patient Experiences. Foley, Geraldine, Timonen, Virpi and Hardiman, Orla – all of Trinity College Dublin Published in American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 2012 Corresponding author: Geraldine Foley HRB Research Fellow School of Social Work and Social Policy Arts Building Trinity College Dublin Ireland foleyg3@tcd.ie geraldinefoley63@gmail.com Acknowledgements: This work is funded by the Health Research Board (HRB) of Ireland 1 Experience of Services as a Key Outcome in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Care: The Case for a Better Understanding of Patient Experiences. Abstract People with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) frequently express dissatisfaction with services. Service user satisfaction with services in ALS care is not always measured and service user perspectives are not usually included when evaluating outcomes of care. There is a lack of consensus on what constitutes satisfaction for service users in ALS care. To date, healthcare professionals’ conceptualisation of outcomes in ALS care has excluded measures of service user satisfaction with services. Exploring the context of the ALS service user experience of care will identify a conceptual framework that will include the domains of satisfaction with care for service users with ALS. An instrument that draws on the ALS service user perspective of services, developed on the basis of qualitative investigation, should be used to measure satisfaction with services. Key words Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, motor neurone disease, outcomes, satisfaction, experiences, services 2 Introduction Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), otherwise known as motor neurone disease (MND), is a rapidly progressive neurological disorder that results in diffuse motor neuron degeneration within the central nervous system. Up to 60% of people with ALS also experience cognitive impairment, and 15% of the population develop a fronto-temporal dementia. The life expectancy in ALS is 3-5 years. Physical disability affects limb and bulbar function and end-of-life is generally due to respiratory failure 1. The care approach in ALS is palliative from the point of diagnosis 2. A combination of symptomatic management, nutritional and respiratory support, assistive devices, and psychological support including advance directives are considered components of ALS care 3. Outcomes in healthcare are defined as measures of the value of service intervention 4. Outcome measures are usually independent of the service user perspective and include measures pertaining to survival, disease severity and cost, all of which are objective and unambiguous outcomes in healthcare. Healthcare services aim to prolong survival for service users and limit the impact of disease severity. Costbenefit analysis is undertaken to measure the effect of care in relation to the cost of care. The role of healthcare professionals in ALS is care is to provide services that are not only responsive to disease progression but also to service users’ perceptions about 3 services 2. Service users who live with a terminal illness may have different perspectives on care than service providers 5. Furthermore, experiences of care have a strong influence on outcomes for service users with terminal illness 6. Service users with advancing illness shift towards values of self direction and benevolence 7. They may choose interventions based on their perspective and decide about care in the context of the needs of those who support them. In recent years, there has been a shift towards incorporating service users’ perceptions of services (including satisfaction) when judging benefits of care 8. Service user satisfaction is defined as an evaluation of distinct healthcare dimensions 9. Some healthcare services research now compares satisfaction with care against outcomes 10 or measures service user satisfaction with care as an outcome measure 11. Despite positive outcomes in ALS multidisciplinary care, literature that reports on the ALS service user perspective suggests, for the most part, dissatisfaction with services. In highlighting this disparity between outcomes and experiences, we draw on a systematic review of the literature pertaining to service user experience of care and care preferences in ALS 12 and on defined web-based data from the service user perspective. We define multidisciplinary care in ALS and report on the effects of ALS multidisciplinary care. We show that studies of outcomes in ALS multidisciplinary care for the most part neglect the service user perspective. We offer suggestions as to why research in ALS to date has not investigated the relationship between outcomes of care and service user satisfaction with services or indeed measured 4 service user satisfaction with services as an outcome of care. We hypothesise that the inclusion of measures that tap into the ALS service user perspective would yield a different, and fuller, picture of outcomes. We conclude by recommending the construction of an outcome measure that draws on the ALS service user perspective on services. A qualitative investigation of the parameters of the ALS service user experience of services is the first step in developing this new outcome measure. Satisfaction and dissatisfaction with ALS services: the service user perspective The authors undertook a systematic review of recent literature pertaining to service users’ perceptions of and preferences for care in ALS 12. This review identified 43 studies which reported from the service user perspective, of which 20 dealt primarily with service user satisfaction with services. Here, we focus on these 20 studies pertaining to service user satisfaction with services and studies published on ALS service user satisfaction with services since we completed our review. Many studies have identified dissatisfaction with services. Most service users request services, but then confront various problems. These include: absence of specialised (tertiary) care and care co-ordinators; limited access to different healthcare disciplines and assistive devices; and a lack of knowledge about ALS among health care professionals 13-19. Inadequate home care and/or respite care are also problematic for service users 20-21. Delays in diagnosis are common 22-23. Some service users also report dissatisfaction with the way in which the diagnosis is provided and feel they receive inadequate information about the disease and care options following diagnosis 24-25. However, some studies report satisfaction with 5 disclosure 26-28. Studies that focus on the use of assistive devices report satisfaction with the use of these devices 29-35. Service user satisfaction with services has also been captured by defined web-based datasets. An online questionnaire to 247 people with ALS 36 found that service users wished for more information about ALS than what was provided to them. Service users who share health information online, experience greater satisfaction with services and have better outcomes from their perspective 37. Outcomes in multidisciplinary ALS care Multidisciplinary care in ALS refers to specialised care which comprises a number of different healthcare professionals including consultant physicians (in neurology, respiratory, gastroenterology, and palliative care), specialist nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, clinical nutritionists, and social workers. Specialised multidisciplinary ALS clinics are typically secondary or tertiary care facilities and provide both diagnostic and treatment services. They co-ordinate care and interface with primary healthcare professionals and the ALS voluntary sector 38. Multidisciplinary care in ALS achieves positive outcomes for service users and service providers 39-46. Positive outcomes include prolonged survival hospital admissions and in length of hospital stay 43. 39-43 and reduction in ALS multidisciplinary care also improves quality of life for service users in psychological and social domains without increased cost to services 45. 44 Intensive multidisciplinary intervention may 6 also be beneficial in limiting the effects of impairment on patient activity levels 46. The majority of these studies have achieved better outcomes when compared to care which is not multidisciplinary 39,40,43-45. One population based study found no difference in survival between multidisciplinary care and general care 47. Multidisciplinary care is also associated with well managed care at end-of-life 48 and better management of ALS symptoms 49 in line with ALS practice parameters 50-52. What explains the paradox between positive outcomes in ALS multidisciplinary care settings and dissatisfaction with services? It is difficult to gain an understanding of how service user satisfaction with services relates to other outcomes in ALS multidisciplinary care because no studies have tested the relationship between them. However, there is a disparity in the literature between predominantly positive outcomes on the one hand and generally low service user satisfaction on the other hand. We have identified a number of possible explanations for this. The majority of studies that report positive outcomes in multidisciplinary ALS care have done so based on survival and cost 39-43,45. One out-come study reports from 44, but no outcome studies report on the service user perspective on quality of life service user satisfaction with services. Whilst the North American ALS Patient Care Database 49,53 has measured service user satisfaction with services, only one study 18 has used a generic patient satisfaction with care measure and only few studies (using Likert scales) have measured satisfaction with specific aspects of care 27,29,30,33-35. It is also noteworthy that many studies which report on service user satisfaction with 7 services have included participants who may not have accessed ALS multidisciplinary care 14,15,18-21,23,24. Service user satisfaction The outcomes used in ALS multidisciplinary outcome studies until now (survival, cost and physical activity), are conceptually different from satisfaction. Satisfaction with services is subjective; cost and survival are objective. Survival in ALS can be clearly defined and death rate is the least variable and most easily identifiable measure of survival in ALS 54. Cost of services (both direct and indirect) in ALS can also be clearly defined, usually by actual costs 45 or by estimated costs 55. Satisfaction is a more complex construct than survival and cost. Satisfaction with health care services is defined as the extent to which service users’ expectations of services are met across specific domains of care. It constitutes an emotional and/or cognitive evaluation of care. Satisfaction is influenced by numerous factors (including education, expectations of services and acceptance of illness) 56 which have not been controlled for in existing studies on satisfaction with services in ALS. Satisfaction is also influenced by the effects of illness and moderated by the effects of available treatments. It reflects the complex interplay of expectations and experiences of health care services. Although a number of quality of life (QoL) measures 57-60 and a meaning of life measure 61 are used in ALS to capture service users’ views on what is important to them 62-64, they are rarely used to evaluate their perceptions of services or indeed the impact of care from their perspective. This is hardly surprising as QoL 8 measures are self appraisals of wellbeing 65 and can exist independently of specific experiences of health care services. One possible factor for influencing outcomes and satisfaction with services could be care provided by specialised ALS centres versus general neurology care, and it is important to note that the studies that have yielded positive outcomes in multidisciplinary care sampled service users who attended specialised ALS clinics 45. 39- It is also of relevance that the majority of multidisciplinary clinic settings that have sought to measure service user satisfaction report high level of service user satisfaction with healthcare services 49,53 and/or satisfaction with respect to distinct components of care 26-35. Measuring satisfaction with services for terminally ill service users Expert consensus for clinical and service user metrics in palliative care services includes patient satisfaction 8. However, the lack of a conceptual basis for service user satisfaction has resulted in the development of many different measures 66. Service providers and researchers who measure satisfaction among people with lifelimiting conditions conduct patient satisfaction surveys (questionnaires) that assess either overall satisfaction with services (thus aggregating all aspects of care into a global measure of satisfaction) or satisfaction with one or very small number of specific aspects of care, such as assistive devices, information or care providers 67. Satisfaction questionnaires may comprise only domains of care deemed important by service providers and neglect domains of care which service users consider meaningful 68. The use of generic palliative care outcome tools themselves may not 9 necessarily be sensitive to the needs of specific groups including people with ALS 69. ALS is always terminal and in comparison to other conditions (including cancer), there is more certainty regarding the period of time to death. Hence, it is conceivable that the domains of satisfaction with services for ALS service users may differ from the domains of satisfaction with services for other groups who live with terminal illness. Conceptualisation of ‘outcomes’ and ‘patient satisfaction’ in ALS care The previous section demonstrated that researchers and service providers in ALS care have to date largely neglected measuring satisfaction with services because of a lack in standard approaches to measuring satisfaction. Neither have researchers and service providers yet tested the relationship between outcomes in ALS care with satisfaction with services because their conceptualisation of outcomes pays little attention to the service user experience. Whilst service providers may view satisfaction in ALS as an important component within care, they generally do not view satisfaction with care as an outcome that is beneficial to facilitating the process of care. The need to identify the domains of satisfaction with care in ALS The dominant view in ALS is that service users’ perspective on care should remain central to the care process 2. Despite this, the experience of services for ALS service users is poorly understood and few studies have investigated the experiences of services from the service user viewpoint. What constitutes domains of satisfaction with services for people with ALS and what influences these domains is unknown. 10 How context e.g. relationship with service providers, cognitive impairment, psychological well-being, coping strategies, severity of illness, symptomatic treatment, carer support, expectations and carer views on services may affect the service user perspective on services, remains unclear. Whilst context does not necessarily determine experiences and/or set the course of interaction between service users and service providers, it does incorporate a set of conditions which influence how people respond to healthcare services. Satisfaction with life and QoL measures are used in ALS care, but no studies have indentified the key domains of ALS service user satisfaction with health and social care services, let alone provided a substantive explanation of how people with ALS experience care services. The parameters of the ALS service user experience of healthcare services have not yet been mapped out. Apart from a limited number of qualitative studies on perceptions about services meaning of care in ALS 73,74 15-17,19,20,22,25,28,70-72 and the little is known about how people with ALS interpret, approach and experience their healthcare services. Further research is required to pinpoint the key parameters of the ALS service user experience of health and social care services. Grounded theory is a research method which builds concepts and theory from qualitative data 75. The use of grounded theory method to identify the key parameters of the ALS service user experience of services will facilitate the development of a theoretical framework that explains how people with ALS understand and use their healthcare services. This framework will include the domains of service user satisfaction with health and social care services in ALS. Such a framework will not only incorporate relevant domains of care but also account for 11 variation, that is, dimensions of the service user experience within these domains. Importantly, grounded theory method is concerned with process, that is, variation in response according to context 75. Response shifts (which are recaliberations of patients’ internal views usually associated with changing circumstance 76) have been identified in ALS 62. This process of adaptation is poorly understood. Hence, a qualitative investigation of the parameters of service users’ experiences of services through grounded theory method will shed further light on this phenomenon. Conclusion This article has shown that studies on outcomes in ALS care have to date paid little attention to service users’ perceptions of services. We argue that the inclusion of measures that include the ALS service user perspective on services would yield a different, and fuller, picture of outcomes. We recommend the development of a new instrument for measuring ALS service users’ satisfaction with services based on an improved understanding of their experience of healthcare services. Identifying the parameters of ALS service users’ use and understanding of services through qualitative research will unearth the key domains of satisfaction with healthcare services in ALS. A qualitative investigation will be the first step in grounding such a measure in the lived experiences and perceptions of ALS service users. Open-ended questions will be posed to respondents who will be invited to recount their experience and views at length; the ensuing qualitative interview data will be analysed with the help of open, axial and selective coding, a largely inductive process which will yield the main categories of the ALS service user experience and a theory to explain relationships between these categories. The main parameters of the 12 service user experience will be translated into a set of questions and responses (scales) that measure those parameters 77 and tested for reliability and validity with a variety of ALS populations as per standard survey design principles. This in turn will provide a measure to be used in quantitative studies of service user satisfaction with ALS healthcare services. The use of such a measure with large and randomly sampled populations where key variables are controlled for will for the first time, give an accurate and representative picture of ALS service users’ views on the services that they receive. The measurement of the key domains of care through the use of such a scale will enable researchers and service providers to measure key components of the service user experience of ALS services and to test the relationship between service users’ satisfaction with services and other outcomes of care. This will help to improve the quality of care and promote services that are driven by service user need. It will also improve the utility of ALS services and be a useful tool in the cost-benefit analysis of ALS healthcare services. References 1. Chio A, Logroscino G, Hardiman O et al. Prognostic factors in ALS: a critical review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009; 10: 310-323 2. Oliver D, Borasio GD, Walsh D. Palliative care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. From diagnosis to bereavement. 2nd ed. Oxford: University Press; 2006 13 3. Mitsumoto H, Rabkin J. Palliative care for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. “Prepare for the worst and hope for the best”. JAMA. 2007; 298: 207-216 4. Kane RL. Understanding Health Care Outcomes Research. 2nd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones Bartlett; 2006 5. Rodriguez KL, Young AJ. Patients’ and healthcare providers’ understanding of life-sustaining treatment: Are perceptions of goals shared or divergent? Soc Sci Med. 2006; 62: 125-133 6. Normand C. Measuring outcomes in palliative care: limitations of QALYs and the road to PaIYs. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009; 38: 27-31 7. Fegg MJ, Wasner M, Neudert C, Borasio GD. Personal values and individual quality of life in palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005; 30: 154-159 8. Weissman DE, Morrison RE, Meier DE. Center to advance palliative care palliative care clinic clinical care and customer satisfaction metrics consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2010; 13: 179-184 9. Pascoe GC. Patient satisfaction in primary healthcare: a literature review and analysis. Eval Program Plan. 1983; 6:185-210 10. Alazri MH, Neal RD. The association between satisfaction with services provided in primary care and outcomes in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2003; 20: 486-490 11. Howard M, Goertzen J, Hutchison B, Kaczorowski J, Morris K. Patient satisfaction with care for urgent health problems: A survey of family practice patients. Ann Fam Med. 2007; 5: 419-424 14 12. Foley G, Timonen V, Hardiman O. Patients’ perceptions of services and preferences for care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. A review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012; 13: 11-24 13. Ng L, Talman P, Khan F. Motor neurone disease: disability profile and service needs in an Australian cohort. Int J Rehabil Res. 2011; 34:151-159 14. van Teijlingen ER, Friend E, Kamal AD. Service use and needs of people with motor neurone disease and their carers in Scotland. Health Soc Care Community. 2001; 9: 397-403 15. Brown JB, Lattimer V, Tudball T. An investigation of patients’ and providers’ views of services for motor neurone disease. B J Neuro Nurs. 2005; 1: 249-252 16. O’Brien MR, Whitehead B, Murphy PN, Mitchell JD, Jack BA. Social services homecare for people with motor neurone disease/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: why are such services used or refused? Palliat Med. 2012; 26: 123131 17. Hughes RA, Sinha A, Higginson I, Down K, Leigh PN. Living with motor neurone disease: lives, experiences of services and suggestions for change. Health Soc Care Community. 2005; 13: 64-74 18. Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, Yates P. Are supportive services meeting the needs of Australians with neurodegenerative conditions and their families? J Palliat Care. 2006; 22: 151-157 19. Murphy J. “I prefer contact this close”: perceptions of AAC by people with motor neurone disease and their communication partners. ACC. 2004; 20: 259-271 15 20. McCabe MP, Roberts C, Firth L. Satisfaction with services among people with progressive neurological illnesses and their carers in Australia. Nurs Health Sci. 2008; 10: 209-215 21. Krivickas LS, Shockley L, Mitsumoto H. Home care of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 1997; 152(Suppl. l): 82-89 22. Hugel H, Grundy N, Rigby S, Young CA. How does current care practice influence the experience of a new diagnosis of motor neurone disease? A qualitative study of current guidelines-based practice. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2006; 7: 161-166 23. Belsh JM, Schiffman PL. The amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patient perspective on misdiagnosis and its repercussions. J Neurol Sci. 1996; 139: 110-116 24. McCluskey L, Casarett D, Siderowf A. Breaking the news: A survey of ALS patients and their caregivers. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2004; 5: 131-135 25. O’Brien MR, Whitehead B, Jack BA, Mitchell JD. From symptom onset to a diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis / motor neurone disease; experiences of people with ALS/MND and family caregivers: a qualitative study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011; 12: 97-104 26. Callagher P, Mitchell D, Bennett W, Addison-Jones R. Evaluating a fast-track service for diagnosing MND/ALS against traditional pathways. B J Neuro Nurs. 2009; 5: 322-325 16 27. Chio A, Montuschi A, Cammarosano S et al. ALS patients and caregivers communication preferences and information seeking behaviour. Eur J Neurol. 2008; 15: 55-60 28. Beisecker AE, Cobb AK, Ziegler DK. Patients’ perspectives of the role of care providers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1988; 45: 553-556 29. Trail M, Nelson N, Van JN, Appel SH, Lai EC. Wheelchair use by patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a survey of user characteristics and selection preferences. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001; 82: 98-102 30. Ward AL, Sanjak M, Duffy K et al. Powered wheelchair prescription, utilisation, satisfaction, and cost for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: preliminary data for evidence-based guidelines. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010; 91: 268-272 31. Vitacca M, Paneroni M, Trainini D et al. At home and on demand mechanical cough assistance program for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010; 89: 401-406 32. Lopes de Almeida JP, Pinto AC, Pereira J, Pinto S, de Carvalho M. Implementation of a wireless device for real-time telemedical assistance of home-ventilated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: a feasibility study. Telemed J E Health.2010; 16: 883-888 33. Nijeweme-d’Hollosy WO, Janssen E, Huis in t Veld R, Spoelstra J, Vollenbroek-Hutten M, Hermens HJ. Tele-treatment of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Telemed Telecare. 2006; 12(Suppl. 1): S31-34 17 34. Gruis KL, Wren PA, Huggins JE. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients’ selfreported satisfaction with assistive technology. Muscle Nerve. 2011; 43: 643647 35. Hossler C, Levi BH, Simmons Z, Green MJ. Advance care planning for patients with ALS: Feasibility of an interactive computer program. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011; 12: 172-177 36. Wicks P, Frost J. ALS patients request more information about cognitive symptoms. Eur J Neurol. 2008; 15: 497-500 37. Wicks P, Massagli M, Frost J et al. Sharing health data for better outcomes on PatientLikeMe. J Med Internet Res. 2010; 12: e19 38. Hardiman O, Traynor BJ, Corr B, Frost E. Models of care for motor neurone disease: setting standards. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2002; 3: 182-185 39. Traynor BJ, Alexander M, Corr B, Frost E, Hardiman O. Effect of a multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) clinic on ALS survival: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003; 74: 1258-1261, 40. Lee JRJ, Annegers JF, Appel SH. Prognosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and the effect of referral selection. J Neurol Sci. 1995; 132: 207-215 41. Sorenson EJ, Mandrekar J, Crum B, Stevens JC. Effect of referral bias on assessing survival in ALS. Neurology. 2007; 68: 600-602 42. Rodriguez de Rivera FJ, Oreja Guevara C, Sanz Gallego I et al. Outcomes of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis attending a multidisciplinary care unit. Neurologia. 2011. DOI:10.1016/j.nrl.2011.01.021 18 43. Chio A, Bottacchi A, Buffa C, Mutani R, Mora G. Positive effects of tertiary centres for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis on outcome and use of hospital facilities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006; 77: 948-950 44. Van den Berg JP, Kalmijn S, Lindeman E et al. Multidisciplinary ALS care improves quality of life in patients with ALS. Neurology. 2005; 65: 1264-1267 45. Van der Steen I, Van den Berg JP, Buskens E, Lindeman E, Van den Berg LH. The costs of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, according to type of care. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009; 10: 27-34 46. Calzada-Sierra DJ, Gomez Fernandez L. The importance of multifactorial rehabilitation treatment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Revista de Neurologia. 2001; 32: 423-426 47. Zoccolella S, Beghi E, Palagano G et al. ALS multidisciplinary clinic and survival; results from a population-based study in Southern Italy. J Neurol. 2007; 254: 1107-1012 48. Mandler RN, Anderson FA, Miller RG, Clawson L, Cudkowicz M, Del Bene M. The ALS patient care database: insights into end-of-life care in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2001; 2: 203-208 49. Miller RG, Anderson F, Brooks BR et al. Outcomes research in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: lessons learned from the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinical assessment, research, and education database. Ann Neurol. 2009; 65(suppl): S24-S28 50. Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ et al. Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality 19 Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009; 73: 1218-1226 51. Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ et al. Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: multidisciplinary care, symptom management, and cognitive/behavioural impairment (an evidencebased review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009; 73: 1227-1233 52. Andersen PM, Borasio GD, Dengler R et al. Good practice in the management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: clinical guidelines. An evidence-based review with good practice points. EALSC Working Group. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2007; 8: 195-213. 53. Miller RG, Anderson FA, Bradley WG et al. The ALS Patient Care Database: Goals, design, and early results. Neurology. 2000; 54: 53-57 54. Gordon PH, Corcia P, Lacomblez L et al. Defining survival as an outcome measure in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2009; 66: 758-761 55. Lopez-Bastida J, Perestelo-Perez L, Monton-Alvarez F, Serrano-Aguilar P, Alfonso-Sanchez JL. Social economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Spain. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009; 10: 237-243 56. Fakhoury WK. Satisfaction with palliative care: what should we be aware of? Int J Nurs Stud. 1998; 35:171-176 57. O’Boyle CA, McGee HM, Hickey A, O’Malley K. Individual quality of life in patients undergoing hip replacement. Lancet. 1992; 339: 1088-1091 20 58. Hickey AM, Bury G, O’Boyle A, Bradley F, O’Kelly FD, Shannon W. A new short form individual quality of life measure (SEIQol-DW): application in a cohort of individuals with HIV/AIDS. BMJ. 1996; 313: 29-33 59. Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, Bui F. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: a measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced diseases. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med. 1995; 9: 207-219 60. Simmons Z, Felgoise SH, Bremer BA, et al. The ALSSQOL. Balancing physical and non-physical factors in assessing quality of life in ALS. Neurology; 67: 1659-1664 61. Fegg MJ, Kramer M, L’hoste S, Borasio GD. The Schedule for Meaning in Life Evaluation (SMiLE): Validation of a new instrument for meaning-in-life research. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008; 35: 356-364 62. Clarke S, Hickey A, O’Boyle C, Hardiman O. Assessing individual quality of life in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 2001; 10: 149-158 63. Chio A, Gauthier A, Montuschi A et al. A cross sectional study on determinants of quality of life in ALS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004; 75: 1597-1601 64. Fegg MJ, Kogler M, Brandstatter M et al. Meaning in life in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010; 11: 469-474 65. Bromberg MB. Quality of life in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2008; 19: 591-605 66. Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Lorenz KA, Mularski RA, Lynn J. A systematic review of satisfaction with care at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008; 56: 124-129 21 67. Sen S, Fawson P, Cherrington G et al. Patient satisfaction in the disease management industry. Dis Manag. 2005; 8: 288-300 68. Aspinal F, Addington-Hall J, Hughes R, Higginson IJ. Using satisfaction to measure the quality of palliative care: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2003; 42: 324-339 69. Hughes RA, Aspinal F, Higginson IJ et al. Assessing palliative care outcomes for people with motor neurone disease living at home. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2004; 10: 449-453 70. Sundling IM, Ekman SL, Weinberg J, Klefbeck B. Patients’ with ALS and caregivers’ experiences of non-invasive home ventilation. Adv Physio. 2009; 11: 114-120 71. Lemoignan J, Ells C. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and assisted ventilation: How patients decide. Palliat Support Care. 2010; 8: 207-213 72. Young JM, Marshall CL, Anderson EJ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients’ perspectives on use of mechanical ventilation. Health Soc Work. 1994; 19: 253-260 73. Bolmsjo I. Existential issues in palliative care: interviews of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Palliat Med. 2001; 4: 499-505 74. Brown JB. User, carer, and professional experiences of care in motor neurone disease. Prim Health Care Res Devel. 2003; 4: 207-217 75. Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2008 76. Wilson I. Clinical understanding and clinical implications of response shift. Soc Sci Med. 1999; 45: 1577-1588 22 77. Coyle J, Williams B. An exploration of the epistemological intricacies of using qualitative data to develop a quantitative measure of user views of health care. J Adv Nurs. 2000; 31: 1235-1243 78. Logroscino G, Beghi E, Hardiman O et al. Effect of referral bias on assessing survival in ALS. Neurology. 2007; 69: 939; author reply 939-940 23