Pediatric Abdominal Emergencies - Pediatric Emergency Medicine

advertisement

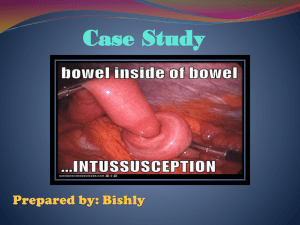

1 PEMdatabase.Org Pediatric Abdominal Emergencies Loren G. Yamamoto, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAP, FACEP Pediatric abdominal emergencies are challenging diagnostic entities (1). Whenever a correct diagnosis is made, a great deal of satisfaction results since significant morbidity and mortality is avoided. Yet, these diagnostic entities are difficult, resulting in frequent misdiagnoses and consequent morbidity and mortality. The purpose of this essay is to familiarize the reader with these entities which include appendicitis, intussusception, malrotation with midgut volvulus and Meckel's diverticulum. For all of these conditions, an early diagnosis is associated with a substantially better outcome, compared to a late diagnosis. Although there are other abdominal emergency conditions, this essay will be limited to covering these four topics. 2 Appendicitis Appendicitis is the most common of the serious abdominal conditions. Without quoting an actual incidence figure, it is only important to realize that children with appendicitis will be encountered frequently, especially in an emergency department. This makes appendicitis one of the most common serious pediatric conditions to be encountered. Parent/patient expectations regarding appendicitis are unforgiving in that since most lay perons have heard of appendicitis and have relatives or friends who have had appendicitis, this should be a very easy diagnosis to make in the minds of most parents/patients. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of appendicitis is difficulty. The misdiagnosis rate is difficult to determine since no one likes to brag about their high misdiagnosis rates in the literature. However, it may be as high as 50%, which means that roughly 50% of the patients who have appendicitis, have seen a physician on a previous encounter for which a different diagnosis (a misdiagnosis) was given. This is probably because roughly 50% of the cases present in an atypical fashion. The more atypical the clinical presentation is, the more likely it is, that a physician will misdiagnose the case (1-6). Adding to the difficulty, is that patients frequently present very early in their clinical course, when only mild and less specific symptoms may be present. Infants and young children are especially difficult to evaluate since they can't speak and their examination is difficult. Their chief complaint is often vomiting, which is often attributed to gastroenteritis. It is almost impossible to perform an adequate examination of the infant abdomen while they are supine on a gurney. It may be better to have the parent carry the child (upright with the child's head on the parent's shoulder) while the examiner wraps his/her hands around the infant's abdomen from behind. The fingers can then be used to press on the abdomen in the RLQ and other areas. Infants are usually content in this position and are easy to examine. Discomfort which occurs from pressing on the abdomen is suspicious for appendicitis, especially if it occurs on the right side. Older infants may still cry because of stranger anxiety, in which case, it is sometimes useful to explain this maneuver to the other parent, who can do this for you when you step out of the room. By utilizing the parent as an examiner, a more accurate exam can be done. Another useful maneuver for infants and young children, is to have 3 the parent bounce the child up and down (similar to an older child jumping). A happy and interactive child suggests the absence of peritonitis, while fussiness with this maneuver should raise the suspicion of peritonitis and appendicitis. Classic symptoms of appendicitis include right lower quadrant pain/tenderness, anorexia, peritoneal signs, fever, nausea, vomiting. Of these, the most important sign is tenderness in the right lower quadrant. Such classic presentations are the minority of presentations. Atypical features that increase the likelihood of a misdiagnosis include abdominal pain in a different location, diarrhea, respiratory symptoms and abdominal pain severity which is mild or minimal. A good appetite and the absence of fever are also misleading (2-6). CBC and acute phase reactants (ESR and CRP) are not very useful in establishing a diagnosis, nor in ruling it out (7-11). In fact, a normal ESR/CRP and/or the absence of a leukocytosis contributes to the likelihood of a misdiagnosis. Pyuria found on urinalysis is often present in appendicitis, but such cases are often misdiagnosed as a urinary tract infection (12). Gynecologic diagnoses may be a misdiagnosis or they may occur concurrently with appendicitis. Plain film abdominal radiographs are most often non-diagnostic. The presence of a fecalith (appendicolith) may be helpful, but this is a rare finding and occasionally, what appears to be a fecalith, may not be. The appearance of fecaliths varies considerably (13) and they are difficult to distinguish from other causes of calcification in the right lower quadrant. Rectal examination is most often nondiagnostic as well since it is unconfortable in children with and without appendicitis (1417). If a patient presents with classic appendicitis, the diagnosis is not likely to be missed. However, in many instances, the presentation will be atypical. Since clinical evaluation, laboratory evaluation and plain film radiographs are often unreliable in establishing or ruling out the possibility of appendicitis, clinicians must frequently consider the use of advanced imaging modalities such as CT scanning and ultrasound. The comparison between the two has been documented in numerous studies (18-32). To summarize these basically, ultrasound is faster, less invasive and less accurate, compared to CT scanning which is slower, results in radiation exposure, requires contrast, but it is more accurate. 4 Ultrasound is highly dependent on the interpreter of the study (i.e., the skill of the ultrasonographer or radiologist). Most studies investigating its diagnostic accuracy have originated from ultrasound supercenters utilizing ultrasound superspecialists. Such expertise is not likely to exist in community general hospitals. Ultrasound is frequently non-diagnostic in that the appendix is not visualized directly. The presence of absence of free fluid in the abdomen may be helpful, but it is not definitive enough. The advantage of ultrasound is that it is non-invasive and it does not expose the patient to radiation. In females, ovarian pathology may be identified as an alternate diagnosis (but only if the patient's bladder is full, required for transabdominal ultrasound). Vaginal probe ultrasound use is generally not feasible in children. CT scanning is more accurate. Most centers utilize GI contrast (either PO or rectal) plus IV contrast. Contrast is not absolutely necessary, but it appears to add to the diagnostic accuracy. Rectal contrast is faster, but it is messy and uncomfortable, making some children fussy during the CT scan. PO contrast is slower since it is preferable for the the contrast to travel down as far as possible (frequently 1 to 2 hours). Vomiting patients can be given 1 to 1.5 mg/kg of Zofran (ondansetran) IV, to help them hold down oral contrast, but this sometimes does not work. Combining ultrasound with CT scan in a strategic fashion requires knowledge of the expertise available in a specific institution. For example, if a highly skilled ultrasonographer is available, it may be advantageous to start with ultrasound. However, if a general adult radiologist is on call for ultrasonography, it may be preferable to go straight to a CT scan. Parents/patients should also understand that if an ultrasound is done first and it is non-diagnostic, they will still be charged for the ultrasound, plus the subsequent CT scan. Whetever advanced imaging modality is selected, 100% accuracy is not guaranteed. A patient with a high clinical probability of appendicitis and an imaging study negative for appendicitis should still be hospitalized. A second opinion to interpret the CT scan can also be requested in some institutions (especially those that utilize teleradiology). Some general hospitals may benefit by utilizing a pediatric radiology group to interpret their CT scans by teleradiology. 5 Surgical consultation has changed dramatically with the use of advanced imaging. In the past, a patient suspected of having appendicitis would require a consultation with a reluctant surgeon who frequently asked questions over the phone regarding the WBC, temperature, location of pain, rebound, etc. Most of these surgical consultations were negative and the accuracy of the surgeon was not perfect. With advanced imaging, consulting a surgeon is now an efficient process consisting of a brief telephone interchange. "Dr. Surgeon, I have a 7 year old with appendicitis confirmed on CT scan." The surgeon replies, "I'll be there." The evolution of this consultation pattern is still maturing. A patient who has a high clinical probability of appendicitis should probably have an immediate surgical consultation, avoiding an advanced imaging study. However, surgeons are loathe to operate on non-appendicitis case as well, since what appears to be appendicitis clinically, may not be such. Thus, even in classic presentations of appendicitis, the consulting surgeon will often order an imaging study to confirm this to assist with the decision on whether to operate. The decison on when to consult a surgeon should depend on the resources available at the institution. In an institution with only one surgeon who was up all night the previous night, it would be preferable to consult this extremely budy and tired individual, only after imaging confirmation of appendicitis. But in an institution with surgical residents or many surgeons immediately available, it would be preferable to consult a surgeon earlier. A suggested algorithm follows: For a patient with a high clinical probability of appendicitis: Go straight to a surgical consultation or advanced imaging study. For all other patients with abdominal pain: Consider starting with an optional abdominal series. If constipation is suspected, administer an enema. If the enema treatment results in 100% resolution of the abdominal pain, then the patient can be discharged with the abdominal pain instruction sheet. Such patients should be able to jump up and down without any pain. However, if pain is still present, then an assessment of the probability of appendicitis (or other serious condition) should be considered and discussed with the parents. In a low risk patient, home observation with specific instructions is acceptable, as long as this is acceptable to the parents and their assessment skills are deemed to be satisfactory. If any party (clinician or parents) are uncomfortable about the possibility of appendicitis, then advanced 6 imaging is indicated. Optional laboratory studies can be ordered simultaneously (CBC, lipase, ALT, UA, chemistry, etc.). In my experience, I have seen patients with appendicitis who present with epigastric pain, left sided pain and minimal pain while they jump up and down. Consider advanced imaging for all causes of abdominal pain. There are more advanced imaging studies being ordered than ever before. CT scans have proliferated to nearly every hospital in the U.S.A. There are two sides of this argument. Some might consider this to be an excessively liberal use of advanced imaging. Others would argue that by restricting advanced imaging use, we are withholding technology from patients. Both arguments are valid, leaving clinicians to make the decision. Clinical Tips: 1. Have the patient cough, then jump up and down. For infants and young children, have the parents bouce the child and observe them for discomfort. 2. Examine small children and infants from the back while the parent is carrying them. 3. Vomiting in infants should be worrisome and not routinely assumed to be gastroenteritis. 4. Utilize advanced imaging liberally. 5. Realize that appendicitis is common, so it is fairly likely that this patient will have it. 6. Although pneumonia is a common cause of abdominal pain, the presence of pneumonia does not rule out the possibility of appendicitis. 7. Provide all patients with a standardized information sheet on abdominal pain. Clinical Pitfalls: 1. Never tell a patient that they DO NOT have appendicitis. This diagnosis is too occult ever be sure about this. Instead, acknowledge the uncertainty honestly and encourage them to return or call if their condition worsens. 7 2. In patients with a high clinical probability of appendicitis, it may be preferable to hospitalize patients with negative abdominal CT scans or ultrasounds (i.e., CT and ultrasound are not 100% accurate). References 1. Schnaufer L, Mahboubi S. Chapter 118-Abdominal Emergencies. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 4th edition, 2000. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp. 1513-1538 2. Horwitz JR, Gursoy M, Jaksic T, Lally KP. Importance of diarrhea as a presenting symptom of appendicitis in very young children. Am J Surg. 1997 Feb;173(2):80-82. 3. Reynolds SL. Missed appendicitis in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 1993;9(1):1-3. 4. Rothrock SG, Skeoch G, Rush JJ, Johnson NE. Clinical features of misdiagnosed appendicitis in children. Ann Emerg Med 1991;20(1):45-50. 5. Rappaport WD, et al. Factors Responsible for the High Perforation Rate Seed in Early Childhood Appendicitis. Am Surg 1989;10(55):602. 6. Bender JD, et al. Childhood Appendicitis: Factors Associated with Perforation. Pediatrics 1985;76(2):301. 7. Gronroos JM. Do Normal Leucocyte Count and C-Reactive Protein Value Exclude Acute Appendicitis in Children? Acta Ped 2001;90:649. 8. Chung JL, et al. Diagnostic Value of C-Reactive Protein in Children With Perforated Appendicitis. Eur J Ped 1996;155(7):529. 9. Lau WY, et al. Leucocyte Count and Neutrophil Percentage in Appendectomy For Suspected Appendicitis. Aust N Z J Surg 1989;59:395. 10. Miskowiak, J., et al. The White Cell Count in Acute Appendicitis. Dan Med Bull 1982;29(4):210. 11. Bower RJ, et al. Diagnostic Value of the White Blood Count and Neutrophil Percentage in the Evaluation of Abdominal Pain in Children. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1981;152(4):424. 8 12. Scott JH III, et al. Abnormal Urinalysis in Appendicitis. J Urol 1983;129(5):1015 13. Yamamoto LG, Goto CS. Appendicoliths. Radiology Cases In Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 1999, Volume 6, Case 18. Available on CD-ROM and online at: www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v6c18.html 14. Brewster GS, et al. Medical Myth: A Digital Rectal Examination Should be Performed on all Individuals with Possible Appendicitis. West J Med 2000;173:207. 15. Jesudason EC, et al. Rectal Examination in Paediatric Surgical Practice Br J Surg 1999;86(2):376. 16. Scholer SJ, et al. Use of the Rectal Examination on Children with Acute Abdominal Pain Clin Ped 1998;37:311. 17. Dickson AP, et al. Rectal Examination and Acute Appendicitis. Arch Dis Child 1985;60(7):666. 18. Sivit CJ, Applegate KE, Stallion A, et al. Imaging evaluation of suspected appendicitis in a pediatric population: effectiveness of sonography versus CT. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(4):977-980. 19. Pena BM, Taylor GA, Fishman SJ, Mandl KD. Costs and effectiveness of ultrasonography and limited computed tomography for diagnosing appendicitis in children. Pediatrics 2000;106(4):672-676. 21. Garcia Pena BM, Mandl KD, Kraus SJ, et al. Ultrasonography and limited computed tomography in the diagnosis and management of appendicitis in children. JAMA 1999;282(11):1041-1046. 22. Rice HE, Arbesman M, Martin DJ, et al. Does early ultrasonography affect management of pediatric appendicitis? A prospective analysis. J Pediatr Surg 1999;34(5):754-758. discussion 758-759. 23. Carrico CW, Fenton LZ, Taylor GA, et al. Impact of sonography on the diagnosis and treatment of acute lower abdominal pain in children and young adults. Am J Roentgenol 1999;172(2):513-516. 24. Ramachandran P, Sivit CJ, Newman KD, Schwartz MZ. Ultrasonography as an adjunct in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a 4-year experience. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(1):164-167; discussion 167-169. 9 25. Wong ML, Casey SO, Leonidas JC, et al. Sonographic diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children. J Pediatr Surg 1994;29(10):1356-1360. 26. Sivit CJ, Newman KD, Boenning DA, et al. Appendicitis: usefulness of US in diagnosis in a pediatric population. Radiology 1992;185(2):549-552. 27. Siegel MJ, Carel C, Surratt S. Ultrasonography of acute abdominal pain in children. JAMA 1991;266(14):1987-1989. 28. Quillin SP, Siegel MJ, Coffin CM. Acute appendicitis in children: value of sonography in detecting perforation. Am J Roentgenol 1992;159(6):1265-1268. 29. Lowe LH, Penney MW, Stein SM, et al. Unenhanced limited CT of the abdomen in the diagnosis of appendicitis in children: comparison with sonography. Am J Roentgenol 2001;176(1):31-35. 30. Sivit CJ, Applegate KE, Berlin SC, et al. Evaluation of suspected appendicitis in children and young adults: helical CT. Radiology 2000;216(2):430-433. 31. Pena BM, Taylor GA, Lund DP, Mandl KD. Effect of computed tomography on patient management and costs in children with suspected appendicitis. Pediatrics 1999;104(3 Pt 1):440-446. 32. Balthazar EJ, Rofsky NM, Zucker R. Appendicitis: the impact of computed tomography imaging on negative appendectomy and perforation rates. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93(5):768-771. Intussusception Intussusception is similar to appendicitis in that this is a condition that must be diagnosed promptly. The consequence is bowel infarction and perforation. Intussusception is most common in children under 2 years of age. However, from 2 to 7 years, it can still occur. After 7, it is unlikely to occur (1-5). There are two common and classic presentations for intussusception: 1) Vomiting with crampy abdominal pain. 2) Lethargic infant. Most patients present with vomiting and crampy abdominal pain. The abdominal manifests as severe crying episodes lasting 1 to 5 minutes separated by 3 to 30 minutes of 10 normal behavior (sometimes quiet and drowsy behavior due to exhaustion) where they have no pain. This cyclic pattern occurs as the peristaltic wave encounters the intussception region. The vomitus does not have to be bilious since the obstruction is usually in the ileocecal region. The lethargic infant pattern is less common and it has been described in multiple case reports, but unlike most case reports, this actually DOES occur. Most pediatric emergency physicians will encounter this several times in their careers. Thus, if an infant presents with lethargy and the diagnostic considerations include sepsis, hypoglycemia, infant botulism, Guillaine Barre syndrome, etc., one should add intussusception to this list of possibilities (6,7). Atypical presentations include older children who have crampy intermittent discomfort without vomiting, vomiting without the crampy abdominal pain, and very early presentations of vomiting that resemble gastroenteritis. Since vomiting is a common chief complaint, it may be difficult to identify the occasional vomiting patient with intussusception. It is useful to ask parents if they think that their child may be having abdominal pain. In most instances of gastroenteritis, parents will respond that they do not think that their child is having abdominal pain. However, in intussusception, pain is usually a prominent part of the chief complaint. The classic triad of intussusception include vomiting, crampy abdominal pain, and currant jelly stool. Currant jelly stool probably occurs less frequently now, since it appears that the diagnosis is being made earlier. A sausage shaped abdominal mass is also part of the classic presentation, and perhaps it should now become part of the classic triad since currant jelly stool is uncommon. This sausage mass can best be palpated in those who have very soft abdomens. In most infants and children with intussusception, the abdomen is very soft once the painful cycle has passed, facilitating the palpation of this mass, usually in the right side of the abdomen. In infants and children who have a lot of muscle tone in their abdominal wall, palpation of the mass, may be very difficult. Currant jelly stool has been alleged to be misleading term because most clinicians don't know what it looks like and it does not occur commonly. Intussusception will more often present with blood in the stool that does NOT resemble currant jelly. Although the term, "currant jelly" has flair and it is easy to remember, it can distract a clinician from 11 considering the possibility of intussusception if the blood in the stool does not resemble currant jelly. Thus, whenever the term "currant jelly" is described in teaching clinicians about intussusception, it should be pointed out that there are more cases of intussuception that have blood in the stool which does NOT resemble currant jelly. In fact, there is not "typical" appearance of the blood in intussusception. Classically, the "currant jelly" appearance is gelatinous red, burgundy or maroon colored blood in the stool. The blood may be mixed more homogenously with the stool resulting in a maroon stool or bloody streaks in the stool. The stool may appear to be normal, but occult blood is detectable on guaiac testing. If the stools are loose, it may have the appearance of dysentary (i.e., bloody diarrhea). Any type of blood in the stool should raise the possibility of intussusception (8,9). What appears to be blood on gross inspection, should always be guaiac'd, since children will frequently ingest red substances (fruit punch and gelatin are common) which is the cause of the red appearance mimicking blood. The intussusception usually originates in the ileocecal region (called ileocecal or ileocolic intussusception). The terminal ileum intussuscepts into the cecum, then up the ascending colon. If allowed to progress, it then proceeds to the left through the transverse colon, then inferiorly down the descending colon. Occasionally, intussusception may originate within the small bowel itself. Ileo-ileal intussusception is uncommon, but when it occurs, it may be difficult to diagnose. Patients with intussusception are frequently dehydrated, so IV fluids are usually indicated. However, patients presenting early or those assessed as low risk initially, may not immediately require an IV. Laboratory studies are not helpful in diagnosing intussusception. Plain film radiographs of the abdomen can be diagnostic, but the findings are frequently subtle. Radiographic signs indicating the presence of intussusception include: the target sign, the crescent sign, the absence of the subhepatic angle, and a bowel obstruction (10-12). All these signs cannot be described sufficiently with words. Examples of these signs can be viewed using the online resources cited. The target sign is a faint doughnut shaped mass in the right upper quadrant. The reason for its radiographic appearance is difficult to understand. Suffice it to say that it is subtle, you must specifically be looking for it, and its presence is almost diagnostic of intussusception. 12 The crescent sign occurs because the leading point of the intussusception (intussusceptum) will often protrude into a gas filled pocket. When this occurs, a crescent shape may result and this is highly indicative of intussusception. The shape of the cresecent will always be in the direction such that the intussusceptum is pointing in the direction of the colon (i.e., upward in the ascending colon, right to left in the transverse colon, and downward in the descending colon). If the shape of the crescent is going the wrong way, then this is not a true crescent sign. Sometimes, the pocket of gas is large, so that if the intussusceptum protrudes into this, the shape will not be that of a crescent. The "crescent sign" should be more accurately called the "intussusceptum protruding into a gas filled pocket sign", but this is too long to say. The absence of the subhepatic angle is present when a soft tissue mass is present in the right upper quadrant obscuring the identification of the inferior liver margin. When this occurs, look carefully for a target sign because it is frequently the target sign itself that is obscuring the liver margin. Without the target sign, the absence of the subhepatic angle is suspicious for intussusception, but the diagnostic probability increases greatly when the target sign is present. Intussusception may also present with a bowel obstruction picture on play film radiographs. The mnemonic double AIM (A-A-I-I-M-M) can be used to remember the causes of a bowel obstruction which include: adhesions, appendicitis, intussusception, incarcerated inguinal hernia, malrotation/volvulus and Meckel's diverticulum. Radiographic criteria for a pediatric bowel obstruction differ from the adult criteria. Pediatric bowel obstructions will usually have a dominant radiographic appearance as a paucity of gas or (not and) bowel dilation (13). The absence or paucity of bowel gas is highly suggestive of a bowel obstruction. Bowel dilation (i.e., distention) criteria is not based on the measured diameter of the bowel, but rather the smoothness of the bowel walls, which indicates the loss of bowel haustration and plication, resulting in a picture resembling sausages or hoses. Intussusception is a common cause of the paucity of gas type of bowel obstruction in infants. Some experts claim that plain film radiographs are almost always abnormal in intussusception (4). However, this is usually determined after the fact. While plain film 13 radiographs can be used to confirm or modify the likelihood of intussusception, normal abdominal radiographs may not be sufficient to rule out intussusception. If there intussusception is suspected, an advanced imaging study must be performed to confirm its presence or to rule it out. A contrast enema is the most definitive study available since a normal contrast enema will rule out the possibility of intussusception. If the contrast enema identifies intussusception, then the pressure from the contrast enema will usually be sufficient to reduce the intussusception, curing the condition immediately. Patients with a high clinical probability of intussusception should have a contrast enema performed. However, a contrast enema is uncomfortable, it results in a higher xray radiation exposure and it has a modest complication rate. Thus, an alternative imaging method may be considered for patients with a low or moderate clinical probability of intussusception. CT scan and ultrasound are capable of diagnosing intussusception. CT scanning is usually done when appendicitis is suspected, but intussusception is found instead. Ultrasound is fairly accurate (14,15), but it is most accurate when the study is being interpreted by a highly skilled ultrasonographer. If an ultrasound is being considered, one must consider whether a normal ultrasound will sufficiently rule out intussusception. In other words, if the radiologist tells me that the ultrasound is normal, am I certain that intussusception is rule out. If significant uncertainly still exists despite a normal ultrasound (i.e., intussusception is still possible), then the ultrasound should not be ordered in the first place. If the ultrasound is positive for intussusception, a contrast enema must be done to attempt reduction. If the ultrasound is negative for intussusception, a contrast enema must still be done to rule it out more definitively. Thus, an ultrasound should only be ordered if the clinical probability of intussusception is low or moderate, and a highly skilled ultrasonographer is available who can reliably rule out intussusception on ultrasound. If a contrast enema is indicated, the options include enemas using air contrast, barium or water soluble contrast (16,17). Most pediatric centers are favoring the use of air contrast enemas. The reasons cited for this preference include a higher reduction success rate and a lower risk of complications (18,19). Both of these claims are difficult to substantiate (20). Air must be pumped in under pressure, while barium is hung from a 14 bag, which presumably provides a steadier pressure gradient. If a bowel perforation occurs during the contrast enema, air is less messy to remove compared to barium (18). However, air flows in to the abdomen rapidly, which may cause respiratory failure (necessitating immediate transabdominal needle decompression). Barium is less likely to cause respiratory failure. A newer option which has been described in the literature is to use saline or air to reduce the intussusception under ultrasound guidance (21,22). This is not done in most U.S. centers; however, it is a trend that may gain popularity. Another consideration is that the first goal of the contrast enema is to determine whether intussusception is present. It is clearly easier to see using barium compared to air. This doesn't appear to matter for highly skilled radiologists, but for non-radiologists such as myself, it is much easier to see with barium. Textbooks covering the topic of intussusception always show a picture of it using a barium contrast study, rather than an air contrast study. That's because it is much easier to see with barium. After all these considerations, the decision of which type of contast to use, should really be left to the radiologist performing the procedure (16,23,24). If the radiologist is very familiar with barium, and unfamiliar with air, then barium should be used and vice-versa. A suboptimal study will result if the radiologist is forced to use a contrast material which he/she is unfamiliar with. The intussusception will usually be identified within the colon. However, with ileo-ileal intussusception which has not yet crossed the ileocecal valve, contrast (air, barium, etc.) must enter the terminal ileum to complete the study. In some instances, the radiologist may have difficulty getting contrast past the ileocecal valve. In such instances, ileo-ileal is not ruled out. Is hospitalization required for all those with intussusception reduced with a contrast enema? It is certainly reasonable to hospitalize these patients for observation or extended bowel rest. Patients who have had symptoms for a prolonged period should be hospitalized in most instances. If the duration of symptoms has been brief, and the child's clinical condition has normalized following intussusception reduction and the parents are reliable and they feel comfortable with discharge to home, then this is reasonable as well. Clinical Tips 15 1. For all patients who present with vomiting, ask parents about the presence of abdominal pain. 2. Plain film signs of intussuception are subtle. Review the sample radiographs in the online references to familiarize yourself with these findings. 3. A pediatric bowel obstruction has a different appearance than an adult bowel obstruction. Most pediatric bowel obstructions are due to serious intestinal conditions requiring immediate intervention. 4. For patients at low risk of intussusception, document that the patient does not exhibit a crampy abdominal pain pattern on observation. 5. Although some experts suggest that air contrast enema is superior to barium enema, this decision is best left to the radiologist performing the procedure. Clinical Pitfalls 1. Bloody diarrhea is often due to bacterial dysentary such as shigella. However, intussusception is a possible cause. 2. Currant jelly stools occur in the minority of cases. Any type of blood in the stool may be due to intussusception. 3. Ordering an ultrasound for intussusception is a difficult decision and it should depend on the diagnostic skill of the ultrasonographer. If the radiologist is unable to rule out intussusception via ultrasound, then an ultrasound study should not be done in the first place. 4. Intussusception cannot be totally ruled out unless contrast has entered the terminal ileum. 5. Failure to recognize a bowel obstruction can have serious consequences since many of the conditions causing a bowel obstruction must be corrected soon. References 1. Schnaufer L, Mahboubi S. Chapter 118-Abdominal Emergencies. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 4th edition, 2000. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp. 1513-1538. 16 2. Kuppermann N, O'Dea T, Pinckney L, Hoecker C. Predictors of intussusception in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154(3):250-255. 3. Luks FI, Yazbeck S, Perreault G, Desjardins JG. Changes in the presentation of intussusception. Am J Emerg Med 1992;10(6):574-576. 4. Eklof O, Hartelius H. Reliability of the abdominal plain film diagnosis in pediatric patients with suspected intussusception. Pediatr Radiol 1980;9(4):199-206. 5. Stein M, Buchta R, Raszynski A, Nyhan WL. Intussusception. West J Med 1979;130(1):35-42. 6. Hickey RW, Sodhi SK, Johnson WR. Two children with lethargy and intussusception. Ann Emerg Med 1990;19(4):390-392. 7. Heldrich FJ. Lethargy as a presenting symptom in patients with intussusception. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1986 Jul;25(7):363-365. 8. Yamamoto LG, Morita SY, Boychuk RB, Inaba AS, Rosen LM, Yee LL, Young LL. Stool Appearance in Intussusception: Assessing the Value of the Term "Currant Jelly". Am J Emerg Med 1997;15(3)293-298. 9. Losek JD, Fiete RL. Intussusception and the diagnostic value of testing stool for occult blood. Am J Emerg Med 1991;9(1):1-3. 10. Young LL, Yamamoto LG. The Stomach Flu? - The Target, Crescent, and Absent Liver Edge Signs Radiology Cases In Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 1994, Volume 1, Case 2. Available on CD-ROM and online at: www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v1c02.html 11. Yamamoto LG. Find the Intussusception Target and Crescent Signs. Radiology Cases In Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 2002, Volume 7, Case 18. Available on CD-ROM and online at: www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v7c18.html 12. Yamamoto LG. Lethargy and Vomiting Following Child Abuse. Radiology Cases In Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 1996, Volume 5, Case 10. Available on CDROM and online at: www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v5c10.html 17 13. Chan-Nishina CC, Tim-Sing PML. Test Your Skill In Distinguishing Obstruction From Ileus. Radiology Cases In Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 1995, Volume 3, Case 18. Available on CD-ROM and online at: www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v3c18.html 14. Harrington L, Connolly B, Hu X, et al. Ultrasonographic and clinical predictors of intussusception. J Pediatr 1998;132(5):836-839. 15. Verschelden P, Filiatrault D, Garel L, et al. Intussusception in children: reliability of US in diagnosis--a prospective study. Radiology 1992;184(3):741-744. 16. Calder FR, Tan S, Kitteringham L, Dykes EH. Patterns of management of intussusception outside tertiary centres. J Pediatr Surg 2001;36(2):312-315. 17. del-Pozo G, Albillos JC, Tejedor D, et al. Intussusception in children: current concepts in diagnosis and enema reduction. Radiographics 1999 Mar-Apr;19(2):299319. 18. Pediatr Radiol 1995;25(2):81-8 Perforation during attempted intussusception reduction in children--a comparison of perforation with barium and air. Daneman A, Alton DJ, Ein S, Wesson D, Superina R, Thorner P. 19. Lui KW, Wong HF, Cheung YC, et al. Air enema for diagnosis and reduction of intussusception in children: clinical experience and fluoroscopy time correlation. J Pediatr Surg 2001;36(3):479-481. 20. Maoate K, Beasley SW. Perforation during gas reduction of intussusception. Pediatr Surg Int 1998 Dec;14(3):168-170. 21. Khong PL, Peh WC, Lam CH, et al. Ultrasound-guided hydrostatic reduction of childhood intussusception: technique and demonstration. Radiographics 2000;20(5):E1. 22. Shehata S, El Kholi N, Sultan A, et al. Hydrostatic reduction of intussusception: barium, air, or saline? Pediatr Surg Int 2000;16(5-6):380-382. 23. Poznanski AK. Why I still use barium for intussusception. Pediatr Radiol 1995;25(4):318. 24. Schmit P, Rohrschneider WK, Christmann D. Intestinal intussusception survey about diagnostic and nonsurgical therapeutic procedures. Pediatr Radiol 1999 Oct;29(10):752-761. 18 Malrotation and Volvulus In the normal abdomen, the small bowel is suspended by mesentary which contains the vascular supply to the bowel. This mesentary has a broad attachment to the abdominal wall. When considering the length of the small bowel and its multiple loops and turns (similar to a bowl of spaghetti), it is truly remarkable that the bowel, or parts of it, does not twist on itself (forming a volvulus) more often. The reason for this is the broad mesentary attachment (1,2). Think of this as a broad fan or sheet of tissue suspending the bowel, making it almost impossible for it to twist on itself. In a malrotation, the mesentary is suspended by a stalk containing the vascular supply, rather than a broad fan, which is susceptible to twisting. The term "malrotation" focuses attention to its embryology which has no clinical importance to most of us. This term has a tendency to misguide us on the true importance of its clinical consequence. Malrotation should be renamed "Guts on a Stalk Syndrome" to emphasize the clinical importance this abnormality. Recall from the previous section in intussusception, that the causes of a bowel obstruction include A-A-I-I-M-M. One of the M's stands for malrotation. In a malrotation, i.e., Guts on a Stalk Syndrome (GOSS), a bowel obstruction can occur in two ways. 1) The stalk can compress the duodenum (a phenomenon called Ladd's bands). 2) The entire stalk can twist, which is known as midgut volvulus. The former (Ladd's bands compression of the duodenum) condition is less serious in that it can easily be corrected surgically and time is not a critical factor. However, a midgut volvulus is potentially catastrophic. If the entire stalk twists, then ischemia to the ENTIRE small bowel results. Failure to surgically correct this condition soon, will result in an infarction of the entire small bowel, a condition which requires lifelong TPN (total parenteral nutrition) for survival. Roughly half of those born with malformation (GOSS), will manifest with an acute bowel obstruction during the first few months of life. The remainder will often present acutely with a bowel obstruction at any time in later life. The term "volvulus" is used loosely, but more accurate terminology is preferable. A midgut volvulus involves the entire small bowel twisted on its vascular stalk which 19 occurs in a malrotation. This is truly a serious condition. A sigmoid volvulus is a condition that occurs sometimes in the elderly, in which the sigmoid colon is long and loose, occasionally twisting and trapping a large amount of gas. This can frequently be reduced with a rectal tube. A sigmoid volvulus usually does not result in a bowel obstruction and it usually does not require an immediate surgical procedure. Vovulus of the cecum (cecal volvulus) occurs occasionally, in which the cecum twists. A patient with an acute bowel obstruction requires an immediate evaluation to determine its cause. Symptoms and signs may include vomiting (often bilious), dehydration, abdominal distention, abdominal pain, pallor, etc. Consultation with a surgeon and/or pediatric radiologist will help to determine the next step in evaluation. Plain film radiographs can usually identify a bowel obstruction, but the radiographic findings are not always obvious (2,3). The radiographic appearance of a bowel obstruction due to a midgut volvulus is variable. An upper GI series would appear to show no passage of barium past the stomach. Careful identification of the duodenum will demonstrate that the duodenal/jejunal junction (ligament of Trietz) is inferior to its normal location (a subtle but reliable sign). Thin barium or water soluble contrast may be able to diffuse into the midgut volvulus revealing a corkscrew appearance of the midgut volvulus twist (4). A barium enema will probably identify the cecum to be in the wrong position. This is highly indicative of a malrotation, but it is possible for the cecum to be in the correct position, despite a malrotation, so a barium enema is not perfect at identifying a malrotation. An ultrasound may be able to demonstrate the midgut volvulus. It may also be able to see an abnormal anatomic location of the superior mesenteric axis that is often (but not always) seen with a malrotation (5). Some patients with malrotation have a phenomenon called intermittent volvulus (2). If a midgut volvulus occurs, it starts with an initial twist. From the initial twist, it could untwist or it could twist tighter. If the patient is lucky enough for it to spontaneously untwist, the symptoms are likely to consist of brief bowel obstruction symptoms followed by relief. Such episodes may recur periodically. A history 20 suggesting intermittent volvulus should prompt an imaging evaluation looking for an asymptomatic malrotation, utilizing one of the imaging studies described above. Clinical Tips: 1. The term "malrotation" should be more accurately called Guts on a Stalk Syndrome. 2. A history suggesting an intermittent volvulus should prompt an imaging evaluation looking for an occult malrotation. Clinical Pitfalls: 1. Failure to recognize a pediatric bowel obstruction can be catastrophic if a midgut volvulus is present. 2. Midgut volvulus is serious emergency requiring immediate diagnosis and urgent surgical intervention. 3. The term "volvulus" by itself is an inadequate description of this clinical condition. 1. Schnaufer L, Mahboubi S. Chapter 118-Abdominal Emergencies. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 4th edition, 2000. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp. 1513-1538 2. Rosen LM, Yamamoto LG. Abdominal Pain and Vomiting in a 7-Year Old. Radiology Cases In Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 1995, Volume 2, Case 8. Available on CD-ROM and online at: www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v2c08.html 3. Chan-Nishina CC, Tim-Sing PML. Test Your Skill In Distinguishing Obstruction From Ileus. Radiology Cases In Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 1995, Volume 3, Case 18. Available on CD-ROM and online at: www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v3c18.html 4. Yamamoto LG. Bilious vomiting in a 3-month old. Radiology Cases In Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 1995, Volume 3, Case 17. Available on CD-ROM and online at: www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v3c17.html 21 5. Zerin JM, DiPietro MA. Superior mesenteric vascular anatomy at US in patients with surgically proved malrotation of the midgut. Radiology 1992;183(3):693694. Meckel's Diverticulum Meckel's diverticulum is a special diverticulum located in the jejunum or ileum. It has several distinct clinical consequences (1,2). It contains gastric mucosa, so it may secret acid and cause a bleeding ulcer. In such instances, painless rectal bleeding may be the presenting complaint. A "Meckel's scan" (nuclear medicine scintigraphy) can be done to identify this condition. The radioisotope is taken up by gastric mucosa, so it will typically image the stomach, but if a Meckel's diverticulum is present, the scan will identify the stomach plus an ectopic source of acid secreting gastric mucosa. Barium enema and upper GI series will often fail to identify the Meckel's diverticulum. Meckel's diverticulum is a diverticulum (a tubular pouch), therefore, it may become inflammed similar to the appendix resulting in Meckel's diverticulitis (3). The clinical picture may be similar to acute appendicitis, but the pain may be in an atypical location. This is another reason why abdominal pain in areas other than the right lower quadrant could still be serious. In some instances, the appendicitis pain is located elsewhere, and in rarer instances, it is a Meckel's diverticulitis causing the symptoms. The Meckel's diverticulum may occasionally ulcerate and perforate which may present as a bowel perforation without the preceding diveriticulitis symptoms. A CT scan or ultrasound can sometimes identify this, but this can be a difficult diagnosis to establish prior to surgery. A Meckel's diverticulum may be attached to the abdominal wall and form a stalk like connection, around which a volvulus can occur (4). A Meckel's diverticulum may form a lead point for an intussusception (often ileo-ileal intussusception). In both such presentations, the patient may present with symptoms of a bowel obstruction. In summary, Meckel's diverticulum, presents with a diverse set of serious acute surgical conditions. Many textbooks describe Meckel's diverticulum following the rule 22 of 2's: a) 2% of the population are born with a Meckel's. b) Only 2% of those with a Meckel's manifest clinical problems. c) Usually located 2 feet proximal to the terminal ileum and the diverticulum is usually 2 inches long. d) Symptoms commonly manifest at age 2 years. 1. Goglia RP. Meckel's Diverticulum. In: Ashcraft KW, Holder TM (eds). Pediatric Surgery, second edition. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, 1993, pp. 435-439. 2. Schnaufer L, Mahboubi S. Chapter 118-Abdominal Emergencies. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 4th edition, 2000. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp. 1513-1538 3. Yamamoto LG. Periumbilical Abdominal Pain (Meckel's diverticulitis case). Radiology Cases In Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 1996, Volume 4, Case 9. Available on CD-ROM and online at: www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v4c09.html 4. Yamamoto LG. Bowel Obstruction With Intra-Intestinal Sand (A case of a bowel obstruction and midgut volvulus due to a Meckel's diverticulum). Radiology Cases In Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 1996, Volume 5, Case 19. Available on CDROM and online at: www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v5c19.html