“Fastrack” post-operative management protocol for patients with

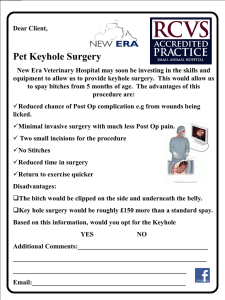

advertisement

“FASTRACK” PROTOCOLS IMPROVE OUTCOME FOR COLORECTAL SURGERY Anthony J. Senagore, MD,MS. Krause-Lieberman Chair in Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery Department of Colorectal Surgery Cleveland Clinic Foundation, 9500 Euclid Avenue, A-30 Cleveland, Ohio 44195, USA email: senagoa@ccf.org Introduction Ttraditionally, postoperative stay following major gastrointestinal surgery has been between five and ten days, with recent Medicare data revealing a mean length of stay of 11.3 days for DRG 148. The emphasis on reducing resource utilization brought about by transitions in payment for medical services, coupled with improved understanding of perioperative physiology have significantly reduced the hospitalization after colectomy. A further pressure reducing length of stay after colectomy has been the greater use of minimally invasive surgical techniques which have been associated with postoperative stays of 2.1 to 4.5 days. . . A variety of factors contribute to the length of stay including inadequate analgesia, nausea and vomiting, delay in ileus resolution, and stress-induced organ dysfunction. In addition, iatrogenic factors including use of nasogastric tubes, transabdominal drains, and enforced malnutrition and bed rest all adversely affect patient recovery after colectomy. Kehlet et al have recently attempted to employ a multimodal rehabilitation program aimed at reducing both the physiologic and iatrogenic 1 factors delaying post-operative recovery. The key components of this program are routine use of thoracic epidural anesthesia and analgesia with local anesthetics, and early feeding coupled with the use of cathartics. Using this approach they were able to produce a median postoperative stay of two days after elective sigmoid colectomy in an initial group of 18 patients. These results were maintained in a larger cohort of 60 patients, who demonstrated a median stay of two days, and included 32 patients discharged within 48 hours. A number of authors have described perioperative care plans, although not routinely using pre-emptive epidural analgesia and oral cathartics. These plans have consistently reduced length of stay, however they have been associated with relatively high early readmission rates of 9-11%. In addition, many of the protocols have altered discharge criteria from typically accepted thresholds by allowing discharge on clear liquids without any evidence of return of bowel function. Finally, these pathways are generally reserved for patients undergoing relatively straightforward, uncomplicated colonic resections. We have employed a similar conceptual approach to “fast-track” recovery after colectomy for both laparoscopic resections and complex re-operative bowel resection and pelvic surgery. A key component of success in our experience has been to carefully explain the principles of the ‘fast-track’ care to each patient prior to surgery. It is important to describe the daily benchmarks expected for the patient (including discharge criteria) prior to admission and to reinforce the same message daily. We avoid the routine use of NG tubes after surgery and limit the use of abdominal drains. Patients are expected to walk the evening of surgery if at all possible and are ambulated at least 5 times per day thereafter. The initial meal offered is full liquids followed by advancement to a GI diet as soon as tolerated. We have not routinely employed epidural analgesia however attempts are made to transfer all patients to oral narcotic based analgesia regimens supplemented with NSAID’s within 24 hours. 2 We have evaluated this protocol in 58 complex bowel resection patients with a mean age was 44.4 ± 13.5 years (range 13 to 70). Thirty-four patients had undergone one or more previous major laparotomies (58.5%), two had undergone minor laparotomies (3.5%; appendicectomy and cholecystectomy), and 22 had never had a laparotomy (38%). Patients who were classified as being in DRG 148 (n=40) stayed 4.6 ± 1.7 days, significantly longer than those in DRG 149 (n=18) who stayed only 3.5 ± 0.8 days (p=0.01). The presence of a defunctioning loop ileostomy, or a history of previous abdominal surgery did not affect time to discharge. Hospital stay was longer in 8 eight patients who complied poorly with the fastrack protocol (from 4.3 to 5.1 days, p=0.02). There were 4 readmissions within 30 days postoperatively, although none were due to GI failure. We subsequently evaluated the historical length of stay at our institution for patients in DRG 148 and 149 has shown a slight reduction for the year 1999, when compared to the decade from 1991 to 1999 (148: 8.4 vs 9.6 days; 149: 6.4 vs 4.3 days). Utilization of the same care plan for laparsocopic colectomy patients has yielded a mean length of stay of 2.4 days. Our work has identified several issues related to the use and efficacy of these protocols. We believe that the ‘fastrack’ approach is applicable to the large majority of cases undergoing colorectal surgery. However, in contrast to the findings of Basse and colleagues who found that patients do equally well, whatever their status of co-morbidity, we have determined that patients without comorbidity do even better than those with co-morbidity and can achieve hospital stays of only 3.5 ± 0.8 days. This is not affected by prior abdominal surgery and confirms that these clinical pathways should be available to all cohorts of colectomy and pelvic surgery patients. The benefits of early discharge have been variously argued in the literature, with some suggesting only marginal cost savings due to the difference in resource consumption early in the 3 perioperative period. This contention, however assumes that the institution is under no constraints related to hospital occupancy or access to nursing services. Neither is the case at our institution where hospital census routinely runs above 95% and there is a severe nursing shortage in the region. Thus the benefit of safe early discharge allows us to admit another patient for surgery which improves patient access as well as providing financial benefit to the institution. . Indeed, as Taheri and colleagues have themselves previously argued, the payments received for these patients can be thought of as pure profit (apart from direct expenses), because staff and institutional costs have been paid already (17). Our experience with these protocols for both open and laparoscopic colectomy have lead to several conclusions. First, the use of a ‘fastrack’ protocol is well tolerated by all patient cohorts regardless of co-morbidity or complexity of procedure. Second, the protocol permits rapid recovery and early discharge from hospital, without adverse events related to the accelerated nature of the postoperative care. Third, the approach is enthusiastically embraced by the educated patients. The ability of the modern abdominal surgeon to embrace these concepts of enhanced recovery after surgery has the potential of allowing patients to be discharged significantly earlier from hospital, reducing rates of nosocomial infection, allowing more efficient use of hospital beds and reducing hospital costs. 4 SELECTED REFERENCES 1. Schoetz DJJ, Bockler M, Rosenblatt MS, et al. 'Ideal' length of stay afer colectomy: whose ideal? Dis Colon Rectum 1997; 40:806-10. 2. Retchin SM, Pinberthy L, Desch C, et al. Perioperative management of colonic cancer under Medicare risk programs. Arch Int Med 1997; 157:1878-84. 4. Pearson SD, Goulart-Fisher D, Lee TH. Critical pathways as a strategy for improving patient care. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123:941-8. 5. Archer SB, Burnett RJ, Flesch LV, et al. Implementation of a clinical pathway decreases length of stay and hospital charges for patients undegoing total colectomy and ileal pouch/anal anastomosis. Surgery 1997; 122:699-705. 6. Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth 1997; 78:606-17. 7. Kehlet H, Mogensen T. Hospital stay of 2 days after open sigmoidectomy with a multimodal rehabilitation programme. Br J Surg 1999; 86:227-30. 8. Basse L, Jakobsen DH, Billesbolle P, et al. A clinical pathway to accelerate recovery after colonic resection. Ann Surg 2000; 232:51-7. 9. McClane SJ, Senagore AJ, Marcello P. Experience-based post-operative care in laparoscopic-assisted colectomy reduces length of stay. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43:A55. 10. Bardram L, Funch-Jensen P, Jensen P, et al. Recovery after laparoscopic colonic surgery with epidural analgesia and early oral nutrition and mobilisation. Lancet 1995; 345:763-4. 11. Binderow SR, Cohen SM, Wexner SD, Nogueras JJ. Must early postoperative oral intake be limited to laparoscopy? Dis Colon Rectum 1994; 37:584-9. 5 12. Reissman P, Teoh T-A, Cohen SM, et al. Is early feeding safe after elective colorectal surgery? A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 1995; 222:73-7. 13. Di Fronzo LA, Cymerman J, O'Connell TX. Factors affecting early postoperative feeding following elective open colon resection. Arch Surg 1999; 134:941-6. 14. Bradshaw BCG, Liu SS, Thirlby RC. Standardized perioperative care protocols and reduced length of stay after colon surgery. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 186:501-6. 15. Behrns KE, Kircher AP, Galanko JA, et al. Prospective randomized trial of early initiation and hospital discharge on a liquid diet following elective intestinal surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 2000; 4:217-21. 16. Taheri PA, Butz DA, Greenfield LJ. Length of stay has minimal impact on the cost of hospital admission. J Am Coll Surg 2000; 190:123-30. 17. Taheri PA, Butz DA, Greenfield LJ. Academic health systems management: the rationale behind capitated contracts. Ann Surg 2000; 231:849-59. 6