Why parents decide to become involved

advertisement

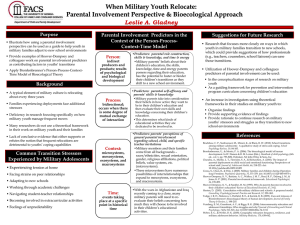

Parents’ motivations for involvement 1 Running head: PARENTS’ MOTIVATIONS FOR INVOLVEMENT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT This is a final draft of the manuscript: Green, C. L., Walker, J. M. T., Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. (2007). Parents’ motivations for involvement in children’s education: An empirical test of a theoretical model of parental involvement. Journal of Educational Psychology. 99, 532-544. Please see APA for a final version of the paper. Parents’ motivations for involvement in children’s education: An empirical test of a theoretical model of parental involvement Christa L. Green Vanderbilt University Joan M. T. Walker Long Island University Kathleen V. Hoover-Dempsey and Howard M. Sandler Vanderbilt University DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT Parents’ motivations for involvement 2 Abstract This study examined the ability of a theoretical model to predict types and levels of parental involvement during the elementary and middle school years. Predictor variables included parents’ motivational beliefs about involvement, perceptions of invitations to involvement from others, and perceived life context variables. Analyses of responses from 853 parents of 1st through 6th grade students enrolled in an ethnically diverse metropolitan public school system in the mid-South of the United States revealed that model constructs predicted significant portions of variance in parents’ home- and school-based involvement even when controlling for family SES. The predictive power of specific model constructs differed for elementary and middle school parents. Results are discussed in terms of research on parental involvement and school practice. Keywords: Parental Involvement, Parents’ Motivation for Involvement, Age-related Differences Parents’ motivations for involvement 3 Parents’ motivations for involvement in children’s education: An empirical test of a theoretical model of the parental involvement process Parental involvement has long been believed to be associated with a range of enhanced school outcomes for elementary, middle and high school students, including varied indicators of achievement and the development of student attributes that support achievement, such as self-efficacy for learning, perceptions of personal control over school outcomes, and self-regulatory skills and knowledge (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 1996; Brody, Flor & Gibson, 1999; Epstein & Van Voorhis, 2001; Fan & Chen, 2001; Frome & Eccles, 1998; Grolnick, Kurowski, Dunlap & Hevey, 2000; Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994; Henderson & Mapp, 2002; Hill & Craft, 2003; Jeynes, 2003; Xu & Corno, 2003). Although parental involvement is an important contributor to children’s positive school outcomes, much less is known about the factors that motivate parents’ involvement practices. A model by Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler (1995, 1997, 2005) provides a strong theoretical framework from which to examine specific predictors of parental involvement (see Figure 1). Grounded primarily in psychological literature, the Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler Model of the Parental Involvement Process proposes three major sources of motivation for involvement (Figure 1). The first is parents’ motivational beliefs relevant to involvement including parental role construction and parental self-efficacy for helping the child succeed in school. The second is parents’ perceptions of invitations to involvement including general invitations from the school (e.g., positive school climate), and specific invitations from teachers and children. The third source is personal life context variables that influence parents’ perceptions of the forms and timing of Parents’ motivations for involvement 4 involvement that seem feasible, including parents’ skills and knowledge for involvement, and time and energy for involvement. In this paper we report findings from an empirical examination of the relative contributions of model constructs, described in more detail below, to parents’ home- and school-based involvement activities. In addition, we consider the influence of student age-related differences in the model’s ability to predict parents’ involvement. The Model Constructs Parents’ Motivational Beliefs Parental role construction. Role activity for involvement incorporates parents’ beliefs about what they should do in relation to their children’s education (HooverDempsey & Sandler, 1995; Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2005). Parents’ beliefs about child rearing and child development and about appropriate home support roles in children’s education influence role construction. Parental role construction also grows from parents’ experiences with individuals and groups related to schooling, and is subject to social influence over time (Biddle, 1986; Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1997). Studies of diverse groups of elementary and middle school students provide empirical support for the power of role construction to influence and shape parental involvement (e.g., Chrispeels & Rivero, 2001; Drummond & Stipek, 2004; Grolnick, Benjet, Kurowski, & Apostoleris, 1997; Hoover-Dempsey, et al., 2005). In general, parents who hold an active role construction are more involved in their children’s education than parents who hold less active role beliefs (Deslandes & Bertrand, 2005; Gutman & McLoyd, 2000; HooverDempsey et al., 2005; Sheldon, 2002). Parents’ motivations for involvement 5 Parental self-efficacy for helping the child succeed in school. Self-efficacy is defined as a person’s belief that he or she can act in ways that will produce desired outcomes; it is a significant factor shaping the goals an individual chooses to pursue and his or her levels of persistence in working toward those goals (Bandura, 1997). Applied to parental involvement, self-efficacy theory suggests that parents make involvement decisions based in part on their thinking about the outcomes likely to follow their involvement activities (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1997; Walker et al, 2005). Like role construction, self-efficacy is socially constructed: it is influenced by personal experiences of success in parental involvement, vicarious experience of similar others’ successful involvement experiences, and verbal persuasion by others (Bandura, 1997). Positive personal beliefs about efficacy for helping one’s children succeed in school are associated with increased parental involvement among elementary, middle and high school students (e.g., Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara & Pastorelli, 1996;Grolnick et al., 1997; HooverDempsey, Bassler, & Brissie, 1992; Seefeldt, Denton, Galper, & Younoszai, 1998; Shumow & Lomax, 2002). Parents’ Perceptions of Invitations to Involvement from Others General school invitations. Several qualities of school environments (e.g., structure, climate, management practices) are associated with enhanced parental involvement (e.g., Griffith, 1998). Invitations are manifest, for example, in the creation of a welcoming and responsive school atmosphere, school practices that ensure that parents are well informed about student progress, school requirements, and school events; they are also reflected in school practices that convey respect for and responsiveness to parental questions and suggestions. Several investigators’ findings underscore the Parents’ motivations for involvement 6 importance of positive school invitations and a welcoming, trustworthy school climate to in supporting parental involvement (e.g., Christenson, 2004; Comer & Haynes, 1991; Griffith, 1998; Lopez, Sanchez, & Hamilton, 2000; Simon, 2004; Soodak & Erwin, 2000). Specific teacher invitations. Specific invitations to involvement from teachers have been identified as motivators of parental involvement in elementary through high school student populations (e.g., Epstein, 1986; Kohl, Lengua, & McMahon, 2002; Simon, 2004). Teacher invitations are influential in part because they underscore the teacher’s valuing of parent contributions to students’ educational success (Adams & Christenson, 2000; Kohl et al., 2002; Patrikakou & Weissberg, 2000). Responding to many parents’ expressed wishes to know more about how they can be helpful in their children’s learning (Corno, 2000; Hoover-Dempsey, Bassler & Burow, 1995), developers of varied intervention programs have reported notable success in increasing the incidence and effectiveness of parents’ involvement activities through teachers’ invitations to participate in specific involvement activities (e.g., Balli, Demo, & Wedman, 1998; Epstein & Van Voorhis, 2001; Shaver & Walls, 1998; Shumow, 1998; Simon, 2004). Specific child invitations. Student invitations can be powerful in prompting parental involvement, in part because parents generally want their children to succeed and are motivated to respond to their children’s needs (e.g., Grusec, 2002; HooverDempsey et al, 1995). Implicit invitations to involvement may emerge as students experience difficulties in school or with aspects of schoolwork (Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2001; Xu & Corno, 1998). Explicit requests or invitations from children also often result in increased parental involvement (e.g., Balli et al., 1998; Deslandes & Bertrand, 2005; Parents’ motivations for involvement 7 Shumow, 1997). As true of all types of invitations to involvement, invitations from the child may be increased by school actions to enhance family engagement in children’s schooling (e.g., Balli et al., 1998; Epstein & Van Voorhis, 2001; Gonzalez, Andrade, Civil, & Moll, 2001; Simon, 2004). Parents’ Perceptions of Life Context Variables Skills and knowledge for involvement. Parents’ perceptions of personal skills and knowledge shape their ideas about the kinds of involvement activities they might undertake (Hoover-Dempsey et al., 1995, 2005). Skills and knowledge are combined in the model because they form a “set” of personal resources that theoretically impact a parent’s decisions about varied involvement opportunities in a similar manner. For example, a parent who feels more knowledgeable in math than in social studies may be more willing to assist with math homework; a parent who feels comfortable and effective in public-speaking may be more likely than a parent who does not believe he or she has such skills to agree to talk about his or her occupation in front of a class of students (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1995). Although skills and knowledge are related to selfefficacy for involvement, they constitute a theoretically and pragmatically distinct construct; individuals with the same level of skills and knowledge may perform differently given variations in personal efficacy beliefs about what one can do with that set of skills and knowledge (Bandura, 1997). Consistent with related empirical work (e.g., Dauber & Epstein, 1993; Delgado-Gaitan, 1992; Hoover-Dempsey et al., 1995; Kay, Fitzgerald, Paradee, & Mellencamp, 1994), inclusion of skills and knowledge in the model suggests that parents are motivated to engage in involvement activities if they Parents’ motivations for involvement 8 believe they have skills and knowledge that will be helpful in specific domains of involvement activity. Time and energy for involvement. Parents’ thinking about involvement is also influenced by their perceptions of other demands on their time and energy, particularly in relation to other family responsibilities and varied work responsibilities or constraints (Hoover-Dempsey et al., 1995; Lareau, 1989). For example, parents whose employment is relatively demanding and inflexible tend to be less involved than parents whose jobs or life circumstances are more flexible (Garcia Coll et al., 2002; Weiss et al., 2003), and parents with multiple child-care or extended family responsibilities may also be less involved, particularly in school-based activities (Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2005) Socioeconomic Status Although not included in the model, we wished to evaluate the predictive power of the model’s constructs relative to the influence of socioeconomic status (SES). SES has often been a variable of interest in studies of parental involvement, and the results have been mixed (Fan & Chen, 2001). On the one hand, some researchers have found SES and parental involvement to be positively related (Brody & Flor, 1998; Fan & Chen, 2001; Lareau, 1989; Stevenson & Baker, 1987). In fact, this connection has often served as a rationale for many intervention programs (e.g., Balli, 1996; Reynolds, 1994; Reynolds, Ou, & Topitzes, 2004), which assume that positive parenting behaviors – the target of interventions - may serve as a protective factor against the negative impact that stressors associated with low SES often have on children’s school achievement (McLoyd, 1998). On the other hand, other researchers have noted that SES variables do not directly explain the often large variability found in levels and effectiveness of involvement within Parents’ motivations for involvement 9 SES groups (Bornstein, Hahn, Suwalsky, & Haynes, 2003; Delgado-Gaitan, 1992; Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1997; Scott-Jones, 1987). Some researchers have argued that such findings indicate that SES variables are not as important as contextual processes that motivate parents’ involvement, such as school invitations to involvement and parents’ social networks (e.g., Sheldon, 2003). Thus, we tested not only model constructs but also the continued ability of model constructs to predict parental involvement practices when controlling for socioeconomic status. Outcome: Parents’ Home-Based and School-Based Involvement Practices Parental involvement has been defined in a variety of ways in the literature (Epstein, 1986; Fan & Chen, 2001). Although involvement is a complex process that often transcends geographic boundaries, researchers have often characterized involvement in two sub-types, home-based and school-based (e.g., Christenson & Sheridan, 2001). Such categories are useful because they are representative of relatively common but distinct activities expected of families in many large, urban public school systems. While more comprehensive measures of involvement activities are available and quite useful for varied purposes (e.g., Epstein, 1986; Epstein & Salinas, 1993; Garcia, 2004), this study offers an examination of a targeted range of involvement activities commonly used by parents of 1st – 6th grade children. Home-based involvement is generally defined in the literature as interactions taking place between the child and parent outside of school (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 2005). These parental behaviors generally focus on the individual child’s learning-related behaviors, attitudes, or strategies, and include parental activities such as helping with homework, reviewing for a Parents’ motivations for involvement 10 test, and monitoring the child’s progress. School-based involvement activities generally include activities typically undertaken by parents at school which are generally focused on the individual child, such as attending a parent-teacher conference, observing the child in class, and watching the child’s performance in a school club or activity. School-based involvement behavior may also focus on school issues or school needs more broadly, such as attending a school open house and volunteering to assist on class field trips. Age-Related Differences in Parental Involvement A second goal of this study was to examine levels and types of parental involvement across the elementary and middle school years. Parental involvement has consistently been shown to decrease as children age, both by grade level and by differences in school structures or school transitions (Eccles & Midgley, 1990; Grolnick, Kurowski, Dunlap, & Hevey, 2000; Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994). There are developmental reasons supporting decreases in parental involvement as the child moves from early to middle childhood and again into adolescence, including children’s increasing needs for independence and increasing focus on peer relationships (Matza, Kupersmidt & Glenn, 2001; Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, & Darling, 1992). However, appropriate parental involvement practices have been shown to increase positive student outcomes throughout children’s schooling, including the high-school years (Bogenschneider, 1997; Dornbusch, Ritter, Leiderman, Roberts, & Fraleigh, 1987; Fehrmann, Keith & Reimers, 1987; Hill & Taylor, 2004; Lamborn, Mounts, Steinberg & Dornbusch, 1991; Steinberg, Elman, & Mounts, 1989). Despite the number of studies that have found the continued positive influence of developmentally appropriate parental involvement on children’s academic achievement, few studies have documented age- Parents’ motivations for involvement 11 related changes in parental involvement from early elementary through middle school grades or the impact of child age or grade level on parents’ motivation for involvement. In a cross-sectional examination of parenting style and homework help, Cooper, Lindsey and Nye (2000) noted that although parents were less likely to be directly involved with homework in high-school than in elementary school, high-school parents were more likely to give autonomy support in relation to their children’s homework activities. Stevenson and Baker (1987), with a cross-sectional sample, and Izzo, Weissberg, Kasprow, and Fendrich, (1999), with a longitudinal examination of 1st – 3rd grade students, both noted that parent-teacher interactions and parent participation at school decreased with each grade level. While these studies noted that involvement generally decreases, discussions about how child age may be related to different facets of parental involvement motivators were not examined. In the results reported below, we examine the influence of child age-related differences on model constructs and parental involvement practices. Summary This study examined the capacity of hypothesized constructs (role construction, personal self-efficacy for involvement, general invitations from the school, specific invitations from the teacher and child, self-perceived skills and knowledge, and selfperceived time and energy) to predict parents’ self-reported involvement in educationrelated activities based at home (e.g., helping with homework) and at school (e.g., attending school functions). Although our theoretical focus was on the modelhypothesized contributions of constructs that are subject to change by school and family action, indicators of family SES were included as a test of the model’s ability to predict Parents’ motivations for involvement 12 parents’ involvement activities when controlling for SES. The influence of child age on parents’ involvement was also examined, with specific attention to the model’s ability to predict levels and types of involvement among parents of elementary and middle school students. Method Participants Participants were 853 parents of 1st through 6th grade children enrolled in a socioeconomically and ethnically diverse metropolitan public school system in the mid-South of the United States. Parents were recruited at two time points (labeled Sample 1 and Sample 2) at different schools through questionnaire packets sent home with, and returned by, children from participating schools. Participants at the two time points were independent. Only one parent filled out a questionnaire per child; if the family had more than one child, they were asked to fill out a questionnaire only for the oldest child at the school. Information on participant demographic variables at each time point is summarized in Table 1. Overall demographic characteristics of participants at the two time points were slightly different; specifically, parents in the first sample had a slightly lower mean education (high-school or equivalent rather than some college), slightly lower mean family income (between $20,000-$30,000 rather than $30,000-$40,000), and the sample contained a slightly higher percentage of Hispanic families. Both samples are more diverse than typically seen in the regional population, with income levels that are grouped around the average per capita income of the region. To ensure that participants in both samples were from the same population and that generalization error based on resampling was minimized, a cross-validation analysis Parents’ motivations for involvement 13 was conducted. First, a developmental sample (Sample 1) was used to find a regression equation for predicting an aggregate parental involvement measure using model constructs. Score estimates were then found for study participants in the cross-validation sample (Sample 2) using the regression equation developed in Sample 1. A correlation was obtained by comparing the predicted cross-validation sample score estimates to the actual scores found in Sample 2. Despite small changes in scales between samples and the number of variables tested, the correlation obtained was considered acceptable (rY’Y = .57, p < .01). Measures Study measures were developed and refined during the course of a long-term project (see Walker et al., 2005 for scale development information); thus, there were slight differences in length and specific items included in the measures used in the two samples. Although we keep the two samples separate when discussing measures, the samples are later combined for analyses and results. All measures (at both time points) underwent face and content validity evaluations by a panel of five persons who had expert knowledge of the constructs being evaluated. All model measures employed a sixpoint Likert-type response scale. Measures of predictor constructs used an ‘agreedisagree’ response scale, whereas the measure of parental involvement practices used a ‘never-to-daily’ response scale. Reliability scores are noted for measures as used in each sample. Parents’ Motivational Beliefs Parental Role Activity Beliefs. Parental role activity beliefs included parents’ beliefs about what they should do and how active they should be in relation to their Parents’ motivations for involvement 14 children’s education (e.g., “It’s my job to explain tough assignments to my child;” “I believe it is my responsibility to volunteer at the school”: Sample 1, seven items, = .67; Sample 2, 10 items, = .83). Factor analysis in previous work indicated that role activity is a single construct (Walker et al., 2005), incorporating parental beliefs about both home- and school-based involvement. Parental Self-Efficacy for Helping Child Succeed in School. Parental sense of efficacy included parents’ beliefs about their personal ability to make a difference in the child’s educational outcomes through their involvement (e.g., “I feel successful about my efforts to help my child learn”; Sample 1, seven items, = .78); Sample 2, five items, = .80. Parents’ Perceptions of Invitations to Involvement from Others Perceptions of General School Invitations to Involvement. These items tap parents’ perceptions that school staff and the school environment make the parent feel like a valued and welcomed participant in the child’s education (e.g., “I feel welcome at this school”: Sample 1 and 2, six items, = .88 and .79, respectively). Perceptions of Specific Teacher Invitations to Involvement. Grounded in part on work by Epstein and Salinas (1993), these items ask parents to report direct requests from the teacher for involvement at home or in school-based activities (e.g., “My child’s teacher asked me or expected me to supervise my child’s homework”: Sample 1, six items, = .81; Sample 2, five items, = .67). Perceptions of Specific Child Invitations to Involvement. This scale measured parents’ perceptions of child requests for parental help or engagement in school-related Parents’ motivations for involvement 15 activities at home or at school (e.g., “My child asked me to help explain something about his or her homework”: Sample 1, six items = .70; Sample 2, five items, = .64). Parents’ Perceptions of Life Context Variables Skills and Knowledge. The scale assessed parents’ perceptions of personal skills and knowledge relevant to involvement in the child’s education (e.g., “I know enough about the subjects of my child’s homework to help him or her”; Sample 1, nine items, = .83; Sample 2, six items, = .82). Although these constructs could be separated, they are conflated here into one construct because, theoretically, they influence parental involvement practices in a similar manner. Time and Energy. This construct included parents’ perceptions of demands on their time, especially those related to employment and family needs that may influence parents’ thinking about the possibilities of involvement (e.g., “I have enough time and energy to attend special events at school”: Sample 1, eight items, = .84; Sample 2, five items, = .81). Again, although these constructs could be separated, they are combined because, theoretically, they affect parental involvement practices similarly. Socioeconomic Status SES generally refers to a measure of an individual or family’s relative economic and social ranking and can be constructed based on father’s education level, mother’s education level, father’s occupation, mother’s occupation, and family income (Bornstein et al., 2003; National Center for Education Statistics’ Glossary, n.d.). We assessed SES with seven separate variables: parent’s highest level of education completed (eight choices, from less than high school to doctoral degree), parent’s occupation (14 choices, from unemployed/retired/student to professional/executive), and number of hours worked Parents’ motivations for involvement 16 per week; the same items were used to assess the spouse’s or partner’s standing in each area. In addition, family income was assessed (seven choices, from less than $5,000 to over $50,000). These variables were entered separately into a single block in regression analyses, consistent with some researchers’ (e.g., Duncan & Magnuson, 2003) suggestions that aggregating or simplifying SES measures ignores the complexity and fluctuations that may characterize the components of family SES. Outcome: Parental Involvement Practices This scale assessed how frequently parents report that they engage in a sample of home-based and school-based involvement activities. Home-based items included statements such as “I kept an eye on my child’s progress” and “Someone in this family talks with this child about the school day” (Sample 1, four items, = .70; Sample 2, five items, = .79). School-based involvement items included statements such as “Someone in this family attends PTA meetings” (Sample 1, six items, = .82; Sample 2, five items, = .71). Age-related Differences Age-related differences in parental involvement were assessed in two sets of analyses described in more detail below; in the first set, age-related differences were assessed by separating each grade level (grades 1st – 6th); in the second set, age-related differences were assessed by separating elementary school grades (grades 1st – 4th) from middle school grades (grades 5th and 6th) in accordance with school structures in the participating school district. Results Parents’ motivations for involvement 17 The two samples were combined for all analyses. Table 2 summarizes descriptive statistics and correlations for all model variables. Multiple hierarchical regressions were conducted to test hypotheses focused on the power of model constructs to predict parents’ home-based and school-based involvement. SES variables were then added to the multiple hierarchical regressions to test the model’s ability to predict involvement when controlling for SES. Finally, age-related differences were examined with ANOVAs comparing 1st-6th grade levels; multiple hierarchical regressions were used with elementary (1st-4th grades) and middle (5th and 6th grades) school parents to test the predictive power of the model. Predictors of Involvement Home-Based Involvement. Multiple hierarchical regressions were conducted using factors in the following blocks to predict parental home involvement: Block 1, motivational beliefs related to involvement (role activity and parental self-efficacy); Block 2, perceptions of invitations to involvement (general invitations from the school, specific teacher invitations, specific child invitations); Block 3, perceived life context variables (skills and knowledge, time and energy). Table 4 summarizes the results. The constructs accounted for a significant portion of the variance (F[7, 852] = 78.32, p < .01; Adj. R2 = .39). Specifically, parental role activity beliefs, parental self-efficacy, specific child invitations, and parental perceptions of time and energy predicted significant amounts of variance. General invitations to involvement from the school, specific teacher invitations, and self-perceived skills and knowledge were not significant predictors, although all three constructs were significantly correlated with home-based involvement (see Table 2). Parents’ motivations for involvement 18 School-Based Involvement. Multiple hierarchical regressions were conducted as described above. Table 4 summarizes the results. The model constructs accounted for a significant 48.8% of the variance (F[7, 852] = 117.09, p < .01) in parents’ reports of school-based involvement; specifically, parental role activity beliefs, parental selfefficacy, specific teacher invitations, specific child invitations, and parental reports of time and energy for involvement were significant predictors. General invitations for involvement from the school and skills and knowledge were not significant predictors, although both constructs were significantly correlated with school-based involvement (see Table 2). Considering SES Table 3 summarizes descriptive statistics and correlations for all SES variables. The multiple hierarchical regressions above were repeated with SES variables added as the first block (motivational beliefs related to involvement in block 2, perceptions of invitations to involvement in block 3, and self-perceived life context in block 4). The SES variables were not significant in predicting variance in parents’ reported home-based involvement, demonstrating that the model constructs continued to be significant predictors of parental involvement even after controlling for SES. However, in predicting school-based involvement, one SES predictor remained significant: spouse/partner’s education ( = .09, t[573] = 3.01, p < .01), although the zero-order correlation between school-based involvement and spouse/partner’s education was not significant (r = .06, ns; see Table 3). Predicting Age-Related Differences in Parental Involvement Activities Parents’ motivations for involvement 19 Differences by Grade Level. To examine the hypothesis that patterns of parental involvement activities are related to child grade level, the sample was first divided into individual grade levels, and the means for each type of involvement were examined. Involvement generally decreased at each grade level across the elementary and early middle school years (Figure 2); home-based involvement was higher than school-based involvement at all grade levels. To determine if differences in involvement between individual grade levels were significant, omnibus significance tests were conducted. We conducted two separate one-way ANOVAs and found significant differences for both types of involvement (Home-based involvement, F[5, 843] = 19.30, p < .01; 2 = .10: School-based involvement, F[5, 843] = 35.91, p < .01; 2 = .18). Although ANOVA analyses indicate differences between grade levels, they do not indicate how the groups differ. Because we had no specific hypotheses about significant differences between grade levels beyond those based on elementary and middle school differences, and because sample sizes differed widely across groups (n = 1st grade: 84; 2nd grade: 85; 3rd grade: 75; 4th grade: 157; 5th grade: 200; 6th grade: 243), planned complex contrasts to determine between-grade-level differences were not conducted. Post-hoc Tukey comparisons indicated that first through third grade significantly differed from fifth and sixth grade on home-based and school-based involvement. This led us to further explore differences based on school type. Differences by School Type: Elementary v. Middle School. To test the hypothesis that involvement decreases from elementary (1st – 4th grade) to middle (5th and 6th grade) school, independent sample t-tests with unequal variances were conducted (Table 5). Parents of elementary school students reported significantly more home-based and Parents’ motivations for involvement 20 school-based involvement than parents of middle school students. A general linear model was conducted on the interactions between school type and all study variables to see if differences in study variables existed for elementary and middle school parents when we predicted home and school involvement (Table 6). Significant differences were found between school type and all study variables (except skills and knowledge) in either homebased or school-based involvement. Hierarchical multiple regressions were then used to explore how well the model fit elementary school parental involvement behaviors and middle school parental involvement behaviors. Although involvement decreased between elementary and middle school, the predictive power of the model was sustained. In elementary school parents (Table 7), model constructs accounted for 27% of the variance of home-based involvement and 47% of the variance of school-based involvement. In the middle school group (Table 8), involvement trends differed: 48% of the variance was accounted for in home-based involvement and 36% of the variance was accounted for in school-based involvement. These differences between home- and school-based involvement among middle and elementary school parents led to further analyses to determine if the differences were significant and to explore possible causes of these differences. Significance tests of the R2 for home- and school-based involvement revealed differences between the two groups: for home-based involvement, the difference between the R2 was .20, (SERsquare1-Rsquare2 = .05), significant at the 95% confidence interval (0.10 to .30); for school-based involvement, R21 – R22 = .11 (SERsquare1-Rsquare2 = .05), which was significant at the 95% confidence interval (.01 to .21). Further examination of regression coefficients suggested Parents’ motivations for involvement 21 that one construct in particular (specific child invitations) was responsible for the high amount of variance predicted in home-based involvement for the middle school group ( = .60 versus .32). Discussion While evidence generally suggests that parental involvement is beneficial for children’s academic success, less is known about parental motivations for involvement and how these motivations influence specific involvement decisions. This study examined the relative contributions of three major psychological constructs (parents’ motivational beliefs, perceptions of invitations to involvement from others, and perceived life context) hypothesized to predict parental involvement decisions, We also examined the model’s continued ability to predict involvement when controlling for SES, and assessed the model’s ability to predict age-related patterns of involvement despite anticipated decreases in parents’ participation across the elementary and middle school years. Findings for a relatively large and diverse set of parents whose children were enrolled in a metropolitan public school system suggest that the model offers a useful framework for understanding what prompts parents’ home-based and school-based involvement. Supporting the value of examining intrapersonal (i.e., parents’ personal beliefs) and interpersonal factors (e.g., perceptions of others’ invitations) in concert, both forms of involvement were predicted by parents’ perceptions of invitations to involvement from others, motivational beliefs, and perceived life context, respectively. Specifically, parents’ home-based involvement was predicted by perceptions of specific child invitations, self-efficacy beliefs, and self-perceived time and energy for Parents’ motivations for involvement 22 involvement. These same constructs, along with perceptions of specific teacher invitations, predicted parents’ school-based involvement. It is interesting to note that selfefficacy beliefs are a strong positive predictor of home-based involvement, but a small negative predictor of school-based involvement; this may be because parents who are strongly motivated to be involved but do not feel efficacious in their involvement efforts are likely to reach out to the school for assistance. The contributions of these psychological constructs are robust even when family status variables such as parents’ income and level of education are included in the analyses. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Delgado-Gaitan, 1992; Scott-Jones, 1987; Sheldon, 2003), these findings suggest that parental involvement is motivated primarily by features of the social context, especially parents’ interpersonal relationships with children and teachers, rather than by SES (even when broadly defined.) Finally, they suggest that the model may be reasonably applied to parents from a wide variety of socioeconomic backgrounds. The relative contributions of model constructs varied according to child age. As expected, involvement decreased as child age increased. Interestingly, motivations for elementary and middle school parents’ involvement at home and school differed. For elementary school parents, home-based involvement was predicted by perceptions of invitations from children, motivational beliefs (i.e., self-efficacy and role activity beliefs), and perceived time and energy for involvement, respectively. This same order of constructs predicted the home-based involvement of middle school parents with the exception of role activity beliefs. This was counter to our expectation that role beliefs would contribute to maintaining home-based involvement during middle school, a period Parents’ motivations for involvement 23 when children typically press for greater independence and schoolwork becomes increasingly difficult. However, these findings may also indicate that parents’ role beliefs about home-based involvement change as children assert greater independence. This possibility is supported by the fact that the majority of variance in middle-school parents’ home-based involvement is accounted for by perceptions of child invitations. For both groups of parents, school-based involvement was predicted most notably by invitations from teachers and children. Other predictors included perceived time and energy and role activity beliefs, although these constructs appeared most salient to parents of middle school children. In contrast to its importance for many parents’ homebased involvement, self-efficacy did not appear to contribute uniquely to school-based participation. Two constructs, parents’ self-perceived skills and knowledge and perceptions of general school invitations, were significantly correlated with outcome variables but did not predict involvement. Multicollinearity may have played a suppressing role; for example, intercorrelations between parental self-efficacy and self-perceived knowledge and skills may have obscured the specific contributions of each. The failure of general school invitations to predict involvement may be related to the correlation with specific teacher invitations, suggesting that general school invitations may generally influence parental involvement only through specific teacher invitations. The failure of general school invitations to predict involvement may also be due to limited variability in school climate across varied schools in the district, although the researchers view this as unlikely given the apparent uniqueness of school climate across many of the participating schools. Other limitations include the potential ‘halo-effect’ bias of parental self-report. Future Parents’ motivations for involvement 24 studies might use multiple methods (e.g., parent interviews in addition to parent survey responses) and acquire information from multiple sources (e.g., teacher, child, and parent reports for some variables). Also, it is important to keep in mind that claims in this study about declines in parental involvement between elementary and middle school are based on cross-sectional rather than longitudinal data. Implications for Research and Practice This study has two specific implications for research in parental involvement. First, when the contributions of SES, parents’ personal beliefs, perceptions of invitations from others, and perceived life context are compared, parents’ interpersonal relationships with children and teachers emerge as the driving force behind their involvement in children’s education. This finding is important because it highlights the reciprocal nature of parent-child and family-school relationships. Second, the model’s differential ability to explain levels of home-based and school-based involvement suggests the importance of carefully defining types of parental involvement. Moreover, distinguishing between parents’ home- and school-based involvement revealed important information about how parents’ participation in children’s education changes and may be sustained across the transition to middle school. Construct definition and developmentally related differences in parents’ thinking and behavior related to parental involvement are issues of increasing concern as the body of research on parental involvement continues to grow. To test the model’s generalizability, a logical next step is to examine its predictive power across cultural groups, school types, and developmental levels. We are currently examining the model’s ability to explain the involvement practices of Latino American and Anglo American parents. Other examinations have compared the model’s capacity to Parents’ motivations for involvement 25 predict the involvement of parents who choose to home-school rather than participate in traditional formal schooling (Green & Hoover-Dempsey, 2007). Although socioeconomic status was included in this study to assess the validity of empirically testing the Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler Model of Parental Involvement, we understand that the contributions of SES to parental involvement and students’ school outcomes are the subject of much discussion in the literature and some disagreement among varied theoretical perspectives. We recommend that future research continue to examine the specific contributions of SES variables to parental involvement decisions. Future research, for example, might examine whether SES variables moderate the relationship between model constructs and parents’ involvement decisions. Although the low correlations between our SES measures and involvement suggests that a moderating effect is unlikely, some researchers (e.g., Desimone, 1999; Lareau, 1989; Spera, 2005; Stevenson & Baker, 1987) have noted that SES (or specific components thereof, e.g., parental education level) is likely an important contributor to understanding parents’ involvement. In addition, it was the goal of this paper to examine the Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler Model of the Parental Involvement Process and to test the model’s ability to predict parental involvement practices. The model suggests that psychological constructs directly impact parental involvement practices, so we have examined the main effects of these variables. Other researchers may be interested in various interactions between the variables; for example, life context may better serve as a moderator rather than as a direct contributor (influencing the degree or type of involvement rather than whether the parent becomes involved; Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1995, 1997). Such interactions may Parents’ motivations for involvement 26 provide an interesting area for future research. In addition, researchers may be interested in employing statistical modeling techniques (such as structural equation modeling) to replicate model findings suggested in this study and to further explore the complexities and relationships of model constructs. If such techniques are used, care should be taken; the Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler model of the parental involvement process was not set up to be investigated as a structural equation model (for the evolution of the model, see Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1995; 1997; Walker et al., 2005). Certain graphical representations in the model may not represent efforts to capture latent variables with manifest variables. For example, we do not necessarily believe that an increase in parent’s perceptions of general invitations from the school will also coincide with an increase in parent’s perceptions of child invitations or teacher invitations. Rather, the model is set up to examine specific questions (why do parents become involved and how does their involvement influence child achievement) in order to make sense of a wide area of research and provide guidance for future empirical investigation. Results from this study may assist researchers interested in applying these techniques to statistical models informed by the Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler model of parental involvement process. Findings also suggest potentially fruitful next steps for school practice. For example, given that home- and school-based involvement relied heavily on specific invitations from teachers and children, parental involvement programs might consider emphasizing in-service teacher training for parental involvement (e.g., Hoover-Dempsey, Walker, Jones & Reed, 2002) and initiatives to increase parent’s school-related interactions with children at home (e.g., Balli, Demo & Wedman, 1998; Epstein & Van Parents’ motivations for involvement 27 Voorhis, 2001; Gonzalez, Andrade, Civil & Moll, 2001; Shumow, 1998). These programs may, in turn, enhance parents’ positive, active engagement at both home and school because they are targeted at increasing parents’ active role construction (e.g., “It’s my job to be involved in my child’s education”) and self-efficacy (e.g., “I can make a positive difference in my child’s education”). Schools might also implement programs that help parents overcome challenges posed by contextual variables, such as time and energy (e.g., offer flexible teacher-parent conference times, give specific time-limited suggestions for how to participate in the child’s homework), and work with families to discern existing involvement practices that may not be well-recognized by the school (e.g., Gonzalez et al., 2001; Trevino, 2004). Consistent with previous findings, we found that parental involvement decreased as children grew older. Yet, at all ages, specific invitations from the child and from the teacher were vital for parental involvement. The contribution of other model constructs varied as a function of age. Future research and parental involvement interventions should continue to examine the impact of development on parental involvement motivations and should take special care to target constructs most vital and appropriate to parents and families at each grade level. Future research and practice should particularly attend to the importance of invitations for parent’s involvement decisions. Parents’ motivations for involvement 28 References Adams, K. S., & Christenson, S. L. (2000). Trust and the family-school relationship: An examination of parent-teacher differences in elementary and secondary grades. Journal of School Psychology, 38, 447-497. Balli, S. J. (1996). Family diversity and the nature of parental involvement. The Educational Forum, 60, 149-155. Balli, S. J., Demo, D. H., & Wedman, J. F. (1998). Family involvement with children's homework: An intervention in the middle grades. Family Relations, 47, 149-157. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman. Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Multifacted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning. Child Development, 67, 12061222. Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent developments in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 12, 67-92. Bogenschneider, K. (1997). Parental involvement in adolescent schooling: A proximal process with transcontextual validity. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 59, 718-733. Bornstein, M. H., Hahn, C., Suwalsky, J. T. D., & Haynes, O. M. (2003). Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development: The Hollingshead Four-Factor Index of Social Status and the Socioeconomic Index of Occupations. In M. H. Bornstein & R. H. Bradley (Eds.), Socioeconomic status, parenting and child development. (pp. 29-82). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Brody, G. H., & Flor, D. L. (1998). Maternal resources, parenting practices, and child Parents’ motivations for involvement 29 competence in rural, single-parent African American families. Child Development, 69, 803-16. Brody, G. J., Flor, D. L., & Gibson, N. M. (1999). Linking maternal efficacy beliefs, developmental goals, parenting practices, and child competence in rural singleparent African American families. Child Development, 70, 1197-1208. 1197-1208. Chrispeels, J., & Rivero, E. (2001). Engaging Latino families for student success: How parent education can reshape parents’ sense of place in the education of their children. Peabody Journal of Education, 76, 119-169. Christenson, S. L. (2004). The family-school partnership: An opportunity to promote the learning competence of all students. School Psychology Review, 33, 83-104. Christenson, S. L., & Sheridan, S. M. (2001). School and families: Creating essential connections for learning. New York: The Guilford Press. Comer, J. P., & Haynes, N. M. (1991). Parent involvement in schools: An ecological approach. Elementary School Journal, 91, 271-277. Cooper, H., Lindsay, J. L., & Nye, B. (2000). Homework in the home: How student, family, and parenting-style differences relate to the homework process. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 464-487. Corno, L. (2000). Looking at homework differently. Elementary School Journal, 100, 529-548. Dauber, S. L., & Epstein, J. L. (1993). Parents’ attitudes and practices of involvement in inner-city elementary and middle schools. In N. F. Chavkin (Ed.), Families and schools in a pluralistic society (pp. 53-71). Albany: SUNY. Parents’ motivations for involvement 30 Delgado-Gaitan, C. (1992). School matters in the Mexican-American home: Socializing children to education. American Educational Research Journal, 29, 495-513. Desimone, L. (1999). Linking parent involvement with student achievement: Do race and income matter? Journal of Educational Research, 93, 11-30. Deslandes, R. & Bertrand, R. (2005). Motivation of parent involvement in secondarylevel schooling. Journal of Educational Research, 98, 164-75. Dornbusch, S. M., Ritter, P. L., Leiderman, P. H., Roberts, D. F., & Fraleigh, M. J. (1987). The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development, 58, 1244-57. Drummond, K. V., & Stipek, D. (2004). Low-income parents’ beliefs about their role in children’s academic learning. Elementary School Journal, 104, 197-213. Duncan, G. J. & Magnuson, K. A. (2003). Off with Hollingshead: Socioeconomic resources, parenting, and child development. In M. H. Bornstein & R. H. Bradley (Eds.), Socioeconomic status, parenting and child development. (pp. 83106). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Eccles, J. S., & Midgley, C. (1990). Changes in academic motivation during adolescence. In R. Montemayor, G. R. Adams, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), From childhood to adolescence (pp. 134-155). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Epstein, J. L. (1986). Parents’ reactions to teacher practices of parent involvement. The Elementary School Journal, 86, 277-294. Epstein, J. L., & Salinas, K. C. (1993). School and family partnerships: Surveys and summaries. Baltimore, MD : Johns Hopkins University, Center on Families, Communities, Schools and Children's Learning. Parents’ motivations for involvement 31 Epstein, J. L., & Van Voorhis, F. L. (2001). More than minutes: Teachers’ roles in designing homework. Educational Psychologist, 36, 181-193. Fan, X., & Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 13, 1-22. Fehrmann, P. G., Keith, T. Z., & Reimers, T. M. (1987). Home influence on school learning: Direct and indirect effects of parental involvement on high school grades. Journal of Educational Research, 80, 330-337. Frome, P. M., & Eccles, J. S. (1998). Parents' influence on children's achievement-related perceptions. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology.74, 435-452. Garcia, D.C. (2004). Exploring connections between the construct of teacher efficacy and family involvement practices: Implications for urban teacher preparation. Urban Education, 39, 290-315. Garcia Coll, C., Akiba, D., Palacios, N., Bailey, B., Silver, R., DiMartino, L., & Chin, C. (2002). Parental involvement in children’s education: Lessons from three immigrant groups, Parenting: Science & Practice, 2, 303-324. Gonzalez, N., Andrade, R., Civil, M., & Moll, L. (2001). Bridging funds of distributed knowledge: Creating zones of practice in mathematics. Journal of Education of Students Placed at Risk, 6, 115-132. Green, C. L., & Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. (2007). Why do parents home-school? A systematic examination of parental involvement. Education & Urban Society, 39, 264-285. Griffith, J. (1998). The relation of school structure and social environment to parent involvement in elementary schools. Elementary School Journal, 99, 53-80. Parents’ motivations for involvement 32 Grolnick, W. S., Benjet, C., Kurowski, C. O., & Apostoleris, N. H. (1997). Predictors of parent involvement in children’s schooling. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 538-548. Grolnick, W. S., Kurowski, C. O., Dunlap, K. G. & Hevey, C. (2000). Parental resources and the transition to junior high. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 10, 465488. Grolnick, W. S., & Slowiaczek, M. L. (1994). Parents' involvement in children's schooling: a multidimensional conceptualization and motivational model. Child Development, 65, 237-252. Grusec, J. E. (2002). Parenting socialization and children’s acquisition of values. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 5: Practical issues in parenting (pp. 143-167). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Gutman, L. M., & McLoyd, V. C. (2000). Parents’ management of their children’s education within the home, at school, and in the community: An examination of African-American families living in poverty. The Urban Review, 32, 1-24. Henderson, A. T., & Mapp, K. L. (2002). A new wave of evidence: The impact of school, family, and community connections on student achievement. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Laboratory. Hill, N. E., & Craft, S. A. (2003). Parent-school involvement and school performance: Mediated pathways among socioeconomically comparable African American and Euro-American families. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 74-83. Hill, N. E., & Taylor, L. C. (2004). Parental school involvement and children's Parents’ motivations for involvement 33 academic achievement. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 161164. Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Bassler, O. C., & Brissie, J. S. (1992). Explorations in parentschool relations. Journal of Educational Research, 85, 287-294. Hoover-Dempsey, K.V., Bassler, O.C., & Burow, R. (1995). Parents’ reported involvement in students’ homework: Parameters of reported strategy and practice. Elementary School Journal, 95, 435-450. Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Battiato, A. C., Walker, J. M. T., Reed, R. P., DeJong, J. M., & Jones, K. P. (2001). Parental involvement in homework. Educational Psychologist, 36, 195-210. Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Closson, K. E., Wilkins, A. S., & Sandler, H. M. (April, 2004). Crossing Cultural Boundaries: Latino Parents' Involvement in Their Children's Education. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA. Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. & Sandler, H. M. (1995). Parental involvement in children’s education: Why does it make a difference? Teachers College Record, 97, 310331. Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. & Sandler, H. M. (1997). Why do parents become involved in their children’s education? Review of Educational Research, 67, 3-42. Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. & Sandler, H. M. (2005). Final Performance Report for OERI Grant # R305T010673: The Social Context of Parental Involvement: A Path to Enhanced Achievement. Presented to Project Monitor, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, March 22, 2005. Parents’ motivations for involvement 34 Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Walker, J. M. T., Jones, K. P., & Reed, R. P. (2002). Teachers Involving Parents (TIP): An in-service teacher education program for enhancing parental involvement. Teaching & Teacher Education, 18, 843-867. Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Walker, J. M. T., Sandler, H. M., Whetsel, D., Green, C. L., Wilkins, A. S. & Closson, K.E. (2005). Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. Elementary School Journal. 106, 105-130. Izzo, C. V., Weissberg, R. P., Kasprow, W. J., & Fendrich, M. (1999). A longitudinal assessment of teacher perceptions of parental involvement in children’s education and school performance. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 817839. Jeynes, W. H. (2003). A meta-analysis: The effects of parental involvement on minority children's academic achievement. Education and Urban Society, 35, 202-218. Kay, P. J., Fitzgerald, M., Paradee, C., & Mellencamp, A., (1994). Making homework work at home: The parents’ perspective. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 27, 550-561. Kohl, G. W., Lengua, L. J., & McMahon, R. J. (2002). Parent involvement in school: Conceptualizing multiple dimensions and their relations with family and demographic risk factors. Journal of School Psychology, 38, 501-523. Lamborn, S. D., Mounts, N. S., Steinberg, L., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development, 62, 1049-1065. Lareau, A. (1989). Home advantage: Social class and parental involvement in elementary education. New York: Basic Books. Parents’ motivations for involvement 35 Lopez, L. C., Sanchez, V. V., & Hamilton, M. (2000). Immigrant and native-born Mexican-American parents’ involvement in a public school: A preliminary study. Psychological Reports, 86, 521-525. Matza, L. S., Kupersmidt, J. B., & Glenn, D. M. (2001). Adolescents' perceptions and standards of their relationships with their parents as a function of sociometric status. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11, 245-272. McLoyd, V. C. (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist, 53, 185–204. National Center for Education Statistics’ Glossary. (n.d.). Retrieved November 1, 2005, from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/glossary/s.asp Patrikakou, E. N. & Weissberg, R. P. (2000). Parents’ perceptions of teacher outreach and parent involvement in children’s education. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 20, 103-119. Reynolds, A. J. (1994). Effects of a preschool plus follow-on intervention for children at risk. Developmental Psychology, 30, 787-804. Reynolds, A. J, Ou, S., & Topitzes, J. W. (2004). Paths of effects of early childhood intervention on educational attainment and delinquency: A confirmatory analysis of the Chicago Child-Parent Centers. Child Development, 75, 1299–1328. Scott-Jones, D. (1987). Mother-as-Teacher in the families of high- and low-income black first-graders. Journal of Negro Education, 56, 21-34. Seefeldt, C., Denton, K., Galper, A., & Younoszai, T. (1998). Former Head Start parents' characteristics, perceptions of school climate, and involvement in their children's education. The Elementary School Journal, 98, 339-351. Parents’ motivations for involvement 36 Shaver, A.V., & Walls, R.T. (1998). Effect of Title I parent involvement on student reading and mathematics achievement. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 31, 90-97. Sheldon, S. B. (2002). Parents’ social networks and beliefs as predictors of parent involvement. Elementary School Journal, 102, 301-316. Sheldon, S. B. (2003). Linking school-family-community partnerships in urban elementary schools to student achievement on state tests. The Urban Review, 35, 149-165. Shumow, L. (1997). Daily experiences and adjustments of gifted low-income urban children at home and school. Roeper Report, 20, 35-38. Shumow, L. (1998). Promoting parental attunement to children’s mathematical reasoning through parent education. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 19, 109-127. Shumow, L., & Lomax, R. (2002). Parental efficacy: Predictor of parenting behavior and adolescent outcomes. Parenting: Science & Practice, 2, 127-150. Simon, B. S. (2004). High school outreach and family involvement. Social Psychology of Education, 7, 185-209. Soodak, L. C., & Erwin, E. J. (2000). Valued member or tolerated participant: Parents’ experiences in inclusive early childhood settings. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 25, 29-41. Spera, C. (2005). A review of the relationship among parenting practices, parenting styles, and adolescent school achievement. Educational Psychology Review, 17, 125-146. Parents’ motivations for involvement 37 Steinberg, L., Elman, J., & Mounts, N. (1989). Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity, and academic success among adolescents. Child Development, 60, 1424-1436. Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Dornbusch, S. M., & Darling, N. (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school environment, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development, 63, 1266-1281. Stevenson, D. L., & Baker, D. P. (1987). The family-school relation and the child's school performance. Child Development, 58, 1348-1357. Trevino, R. E. (2004). Against all odds: Lessons from parents of migrant high-achievers. In C. Salinas & M. E. Fránquiz (Eds.), Scholars in the field: The challenges of migrant education. Charleston, WV: AEL. Walker, J. M. T., Wilkins, A. S., Dallaire, J. P., Sandler, H. M., & Hoover-Dempsey, K.V. (2005). Parental involvement: Model revision through scale development. Elementary School Journal, 106, 85-104. Weiss, H. B., Mayer, E., Kreider, H., Vaughan, M., Dearing, E., Hencke, R., & Pinto, K. (2003). Making it work: Low-income working mothers’ involvement in their children’s education. American Educational Research Journal, 40, 879-901. Xu, J., & Corno, L. (1998). Case studies of families doing third grade homework. Teachers College Record, 100, 402-436. Xu, J., & Corno, L. (2003). Family help and homework management reported by middle school students. The Elementary School Journal, 103, 503-536. Parents’ motivations for involvement 38 Table l Demographic Information on Participants Sample 1 Sample 2 Date of data collection Fall 2002 Fall 2003 Participating public schools 3 elementary 5 elementary 2 middle 4 middle Parent participants Grades 1-6 Grades 4-6 Number 495 358 Mean parent education High school or equivalent Some college Mean family income $20,000-30,000 $30,000-40,000 16.5% 27.4% 5.6% 3.9% Race (% of total participants) African American Asian American Hispanic American 24.5% 6.4% White 30.5% 57.3% Other 7.7% 4.2% 15.2% 0.8% Male 18.5% 17.3% Female 66.8% 82.1% Missing Value 14.7% 0.6% Missing Value Gender, parents (% of total participants) Parents’ motivations for involvement 39 Table 2 Summary of Zero-Order Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Model Variables (N = 853). Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Psychological Motivators 1. Role Activity Beliefs - 2. Parental Self-Efficacy .16*** - 3. General School Invitations .54** .11** - 4. Specific Teacher Invitations .34** -.07* .39** - 5. Specific Child Invitations .30** -.08* .21** .59** - 6. Skills and Knowledge .45** .54** .45** .19** .14** - 7. Time and Energy .47** .36** .36** .19** .23** .66** - 8. Home-based Involvement Behavior .30** .24** .21** .33** .54** .32** .37** - 9. School-based Involvement Behavior .35** -.04 .31** .61** .59** .25** .34** .36** - 4.86 0.67 1-6 - 0.66 1.03 4.65 0.87 1-6 - 0.45 - 0.50 4.82 0.84 1-6 -1.15 1.91 2.54 1.15 1-6 0.64 - 0.43 3.20 0.93 1-6 0.38 0.16 4.64 0.79 1-6 - 0.71 0.68 4.45 0.9 1-6 - 0.75 0.63 4.95 0.99 1-6 -1.17 1.24 2.17 0.94 1-6 1.28 1.47 Invitations to Involvement Life Context Involvement Behaviors Mean SD Possible Range Skewness Kurtosis *p < .05, **p < .01 Parents’ motivations for involvement 40 Table 3 Summary of Descriptive Statistics for Socioeconomic Variables, and Zero-Order Correlations between Socioeconomic Variables and Home Involvement and School Involvement (N = 853). Parent occupation 7.38 5.01 1 – 14 r with Home Involve. -.03 Number of hours worked per week 30.21 16.26 0 – 90 -.07* -.09* Parent’s highest level of education 2.77 1.27 0–7 -.07 -.10** Spouse/partner occupation 5.60 4.96 1 – 14 -.04 -.03 Number of hours spouse/partner worked per week 31.19 17.56 0 – 90 -.01 -.07 Spouse/partner’s highest level of education 3.26 2.25 0–7 .02 .06 Family Yearly Income 4.48 1.92 1–7 -.09** -.19** Variable *p < .05, **p < .01 M SD Range r with School Involve. -.09* Parents’ motivations for involvement 41 Table 4 Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting Home and School Involvement, final model (N = 853). B SE B Role Activity Beliefs .08 .05 .05 Parental Self-Efficacy for Involvement .23 .04 .20** General School Invitations -.02 .04 -.02 Specific Teacher Invitations .00 .03 .00 Specific Child Invitations .54 .04 .51** Skills and Knowledge .05 .05 .04 Time and Energy .14 .04 .13** Role Activity Beliefs .08 .04 .06* Parental Self-Efficacy for Involvement -.08 .03 -.08** General School Invitations .00 .04 .01 Specific Teacher Invitations .29 .03 .36** Specific Child Invitations .31 .03 .31** Skills and Knowledge .05 .05 .05 Time and Energy .18 .04 .17** Variable Dependent Variable: Home Involvement Dependent Variable: School Involvement * p < .05, ** p < .01 F Adj. R2 78.32** .39 117.09** .49 Parents’ motivations for involvement 42 Table 5 Involvement Means and T-Test Results by School Type Home-based Involvement School-based Involvement School type n M (SD) Elementary 401 5.22 (.87) 2.50 (1.07) 443 4.69 (1.02) 1.86 (.66) (1, 787.65) = 10.07* (1, 656.46) = 10.30* .70 .73 (1st – 4th grade) Middle (5th – 6th grade) t - test (unequal variances) d *p < .05 Parents’ motivations for involvement 43 Table 6 Interaction Terms between School Type and Study Variables Predicting Home Involvement and School Involvement F - values Variable Home Involvementa School Involvementb Role Activity Beliefs 28.82** 7.59** Parental Self-Efficacy for Involvement .00 26.39** General School Invitations 9.18** 3.48 Specific Teacher Invitations 9.22** 73.67** Specific Child Invitations 62.75** 6.90** Skills and Knowledge .10 .40 Time and Energy 3.77* 6.85** *p < .05, **p<.01 Note: In this GLM model, a: F [7, 568] = 22.80**, Adj. R2 = .21, b: F [7, 568] = 29.23**, Adj. R2 = .26. Parents’ motivations for involvement 44 Table 7 Summary of Elementary School Students (Grades 1st -4th) Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting Home and School Involvement, final model (N = 401). B SE B Role Activity Beliefs .25 .07 .18** Parental Self-Efficacy for Involvement .22 .05 .22** General School Invitations -.04 .07 -.04 Specific Teacher Invitations .02 .04 .03 Specific Child Invitations .29 .04 .32** Skills and Knowledge .04 .08 .04 Time and Energy .11 .04 .12* Role Activity Beliefs .04 .08 .02 Parental Self-Efficacy for Involvement -.08 .05 -.07 General School Invitations .04 .08 .03 Specific Teacher Invitations .30 .04 .35** Specific Child Invitations .35 .05 .32** Skills and Knowledge .08 .08 .06 Time and Energy .23 .06 .19** Variable Dependent Variable: Home Involvement Dependent Variable: School Involvement * p < .05, ** p < .01 F Adj. R2 21.77** .27 51.01** .47 Parents’ motivations for involvement 45 Table 8 Summary of Middle School Students (Grades 5th and 6th) Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting Home and School Involvement, final model (N = 443). B SE B Role Activity Beliefs -.01 .06 -.00 Parental Self-Efficacy for Involvement .25 .05 .21** General School Invitations -.01 .05 -.01 Specific Teacher Invitations -.02 .05 -.02 Specific Child Invitations .76 .05 .60** Skills and Knowledge .07 .07 .04 Time and Energy .15 .05 .13** Role Activity Beliefs .11 .05 .11* Parental Self-Efficacy for Involvement -.04 .04 -.05 General School Invitations -.05 .04 -.07 Specific Teacher Invitations .23 .03 .32** Specific Child Invitations .23 .04 .27** Skills and Knowledge .05 .05 .07 Time and Energy .11 .04 .15** Variable Dependent Variable: Home Involvement Dependent Variable: School Involvement * p < .05, ** p < .01 F Adj. R2 57.51** .48 36.28** .36 Parents’ motivations for involvement 46 Figure Captions Figure 1. The first level of Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler’s revised theoretical model of the parental involvement process (adapted from Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 2005; Walker et al., 2005). Figure 2: Home-based and school-based involvement means by grade level. Error bars show the 95% confidence interval of the mean. Parents’ motivations for involvement 47 Parents’ Involvement Forms Home Involvement Parents’ Motivational Beliefs Parental Role Construction Parental SelfEfficacy School Involvement Parents’ Perceptions of Invitations for Involvement from Others Parents’ Perceived Life Context General Specific Specific Skills and School Teacher Child Knowledge Invitations Invitations Invitations Time and Energy Parents’ motivations for involvement 48 6.00 5.50 5.00 4.50 Home-based Involvement 3.50 School-based Involvement Means 4.00 3.00 2.50 2.00 1.50 1 2 3 4 Grade level 5 6