Factors - Northern Arizona University

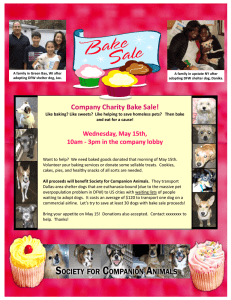

advertisement