Administrative Office St. Joseph`s Hospital Site, L301

advertisement

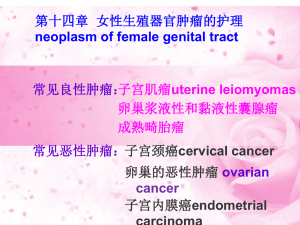

Administrative Office St. Joseph's Hospital Site, L301-10 50 Charlton Avenue East HAMILTON, Ontario, CANADA L8N 4A6 PHONE: (905) 521-6141 FAX: (905) 521-6142 http://www.fhs.mcmaster.ca/hrlmp/ Issue No. 88 QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER June 2006 Update on the Bleeding Time in the Assessment of Bleeding Problems The bleeding time (BT) was developed more than a century ago to evaluate primary hemostasis. This newsletter provides an update on the BT and the alternative test, closure time (CT) measured by the Platelet Function Analyzer (PFA)-100®. Severe defects in primary hemostasis can prolong these tests, but neither the BT nor CT are adequately sensitive to screen for common bleeding problems (1-4). Prolonged BT and CT can reflect drugs or other problems, such as anemia (Table 1) (1-4). Table 1: Summary of Bleeding Time and Closure Time Findings with Common Abnormalities Bleeding Time PFA-100® Closure Time Reduced hematocrit Normal or Normal or Reduced platelet count Normal or Normal or von Willebrand factor abnormalities Normal or Normal or in Type 1, in most other types Common inherited platelet disorders NSAID-induced platelet dysfunction Normal or Normal or mild Normal or Normal or BT and CT are considered optional tests, that are not offered by all laboratories (1,2). BT are not recommended for preand peri-operative testing, as BT do not predict surgical bleeding or adequately detect increased bleeding risks (1,5-10). In selected groups, prolonged BT are associated with increased risks for procedural bleeding (11), however, these risks correlate with other abnormalities (e.g. thrombocytopenia, markers of more severe liver disease) (12). The usefulness of BT, and CT, for screening individuals with significant bleeding histories has been questioned as more specific diagnostic tests are always required (1,2,3,4,13). Like BT, CT has not been accepted as an adequate screen for von Willebrand disease (VWD) and should not be used to monitor therapy (2,4). Locally, the estimated cost of CT are similar to von Willebrand factor screens, which provide more information. Although BT and CT can be prolonged by severe platelet dysfunction, their sensitivity is poor for common defects, such as dense granule deficiency and secretion defects (1-3). One restricted use of the BT is in the assessment of some inherited platelet defects for possible response to desmopressin therapy (13). We are currently analyzing data from a prospective study of individuals with possible bleeding disorders (CHAT study) to see if BT provides helpful information; our preliminary analysis confirms that the BT lacks sensitivity for common defects. BT and CT are normal in many patients on NSAID therapy (1,2,14), and because BT and CT have never been established to predict NSAID (or other drug-related bleeding), this use cannot be recommended. Like the BT, CT should not be used to define “aspirin resistance” or to assess anti-platelet therapy outside of clinical trials (1,2,14). In patients with uremia, BT and CT are not required to manage bleeding, and test prolongations often reflect anemia (1,2,15). In summary, the indications for BT are exceedingly limited. To screen for VWD, we recommend requesting a von Willebrand factor screen, which can be done rapidly on automated instruments when an indication for urgent testing is approved by the laboratory hematologist. For patients who are suspected to have platelet function defects, a hematology consultation is recommended to coordinate the complex, costly testing; performing a BT before referral is not recommended. Summary Messages on the Bleeding Time: Evidence-based indications for this test are extremely limited Inclusion of the BT in hemostasis screens is not recommended because the test is: Inadequate to rule out von Willebrand disease or common platelet disorders - 2 Not of proven value for evaluating NSAID, other drug-related bleeding, or bleeding risks Not of proven value for pre- or peri-operative assessments Does not provide specific diagnostic information Has restricted value in assessments for bleeding (e.g. assessing likelihood of desmopressin responses for some inherited platelet defects) Currently recommended investigations for suspected von Willebrand factor/platelet function defects Take a thorough bleeding history Check the platelet count Do not order a BT Order a “von Willebrand factor screen” to exclude von Willebrand disease Refer the patient to a hematologist to coordinate specialized testing for platelet disorders Acknowledgments This newsletter was prepared in collaboration with the Division of Hematology. Reference List 1. Lind SE. The bleeding time. In: Michelson AD, editor. Platelets. Boston: Academic Press, 2002: 283-289. 2. Hayward CP, Harrison P, Cattaneo M, Ortel TL, Rao AK. Platelet function analyzer (PFA)-100 closure time in the evaluation of platelet disorders and platelet function. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:312-319. 3. Quiroga T, Goycoolea M, Munoz B et al. Template bleeding time and PFA-100 have low sensitivity to screen patients with hereditary mucocutaneous hemorrhages: comparative study in 148 patients. J Thromb Haemost 2004; 2:892-898. 4. Hayward CP. Diagnosis and management of mild bleeding disorders. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program ) 2005;423-428. 5. De Catarina R, Lanza M, Manca G, Strata GB, Maffei S, Salvatore L. Bleeding time and bleeding: an analysis of the relationship of the bleeding time test with parameters of surgical bleeding. Blood 1994; 84:3363-3370. 6. Lind SE. The bleeding time does not predict surgical bleeding. Blood 1991; 77:2547-2552. 7. Barber A, Green D, Galluzzo T, Ts'ao CH. The bleeding time as a preoperative screening test. Am J Med 1985; 78:761-764. 8. Burns ER, Lawrence C. Bleeding time. A guide to its diagnostic and clinical utility. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1989; 113:1219-1224. 9. Gewirtz AS, Miller ML, Keys TF. The clinical usefulness of the preoperative bleeding time. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1996; 120:353-356. 10. Gewirtz AS, Kottke-Marchant K, Miller ML. The preoperative bleeding time test: assessing its clinical usefulness. Cleve Clin J Med 1995; 62:379-382. 11. Boberg KM, Brosstad F, Egeland T, Egge T, Schrumpf E. Is a prolonged bleeding time associated with an increased risk of hemorrhage after liver biopsy? Thromb Haemost 1999; 81:378-381. 12. Violi F, Leo R, Vezza E, Basili S, Cordova C, Balsano F. Bleeding time in patients with cirrhosis: relation with degree of liver failure and clotting abnormalities. C.A.L.C. Group. Coagulation Abnormalities in Cirrhosis Study Group. J Hepatol 1994; 20:531-536. 13. Hayward CP, Rao AK, Cattaneo M. Congenital platelet disorders: overview of their mechanisms, diagnostic evaluation and treatment. Haemophilia 2006; 12 Suppl 3:128-136. 14. Michelson AD, Cattaneo M, Eikelboom JW et al. Aspirin resistance: position paper of the Working Group on Aspirin Resistance. J Thromb Haemost 2005; 3:1309-1311. 15. Sohal AS, Gangji AS, Crowther MA, Treleaven D. Uremic bleeding: Pathophysiology and clinical risk factors. Thromb Res 2006; 118:417-422. Dr. Catherine Hayward, MD PhD FRCP(C) Discipline of Hematology Hamilton Regional Laboratory Medicine Program McMaster University Health & Science Centre