PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University

Nijmegen

The following full text is a publisher's version.

For additional information about this publication click this link.

http://hdl.handle.net/2066/91314

Please be advised that this information was generated on 2015-01-31 and may be subject to

change.

Persistent m edically unexplained sym ptom s

in primary care

The patient, the doctor and the consultation

T im C. o ld e H artm an

Colophon

This thesis has been prepared by the D epartm ent of Prim ary and C om m unity Care of the Radboud U niversity Nijmegen

Medical Centre, the Netherlands. The Departm ent of Prim ary and Com m unity Care participates in the N etherlands School

of Prim ary Care research (CaRe), w hich has been acknowledged by the Royal N etherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

(KNAW) in 1995.

Design:

Joost Perik

Photo W aal Bridge:

Edw in H obert (ww w .edw inenleonie.nl)

Penrose triangle:

by Oscar Reutersvärd, 1934

Layout:

Joost Perik

Digital version of thesis:

Tables:

Joost Perik, by an idea of Fons v an Bindsbergen

QR-code:

Lea Peters

Print:

Ipskam p Drukkers, Enschede (w w w .ipskam pdrukkers.nl)

ISBN:

978-94-91211-99-7

Financial support

This thesis w as made possible by grants of:

-

ZonM w (the N etherlands O rganization for H ealth Research and Developm ent, grant no. 920-03-339)

-

D epartm ent of Prim ary and C om m unity Care, R adboud U niversity Nijmegen Medical Centre

-

SBOH, em ployer of general practitioner trainees

SBCH—

ZonMw

Nijmegen, 2011

Copyright

© T.C. olde H artm an, Nijmegen, the N etherlands, 2011. All rights reserved. No part of this book m ay be reproduced or

transm itted in any form, by print, photo print, microfilm or otherwise, w ithout prior w ritten perm ission of the holder of the

copyright.

Niets uit deze uitgave m ag w orden verm enigvuldigd e n /o f openbaar gemaakt door m iddel van druk, fotokopie,

microfilm, of w elke andere wijze dan ook, zonder schriftelijke toestem m ing van de auteur.

Persistent m edically unexplained symptoms

in primary care

The patient, the doctor and the consultation

E en w etenschap p elijk e p ro ev e op h et gebied v a n de

M edische W eten sch ap p en

Proefschrift

te r v erkrijg in g v a n de g raa d v a n doctor

aa n de R ad b o u d U n iv ersiteit N ijm egen

op gezag v a n de rector m agnificus prof. m r. S.C.J.J. K ortm ann,

volgens b eslu it v an h et college v an decanen

in h et o p en b a ar te v e rd e d ig e n op d o n d e rd a g 13 o k to b er 2011

om 13.00 u u r precies

door

Tim Christian olde Hartman

g eboren op 13 m a a rt 1977

te Alm elo

Promotor:

Copromotoren:

D hr. prof. dr. C. v a n W eel

D hr. dr. P.L.B.J. Lucassen

D hr. dr. H .C.A.M . v a n Rijswijk

Manuscriptcommissie:

M w . prof. dr. A.E.M. Speckens (voorzitter)

D hr. prof. dr. B.G. v a n E ngelen

D hr. prof. dr. C.F. D ow rick (U niversity of L iverpool, Liverpool)

Paranimfen:

D hr. drs. H.J. M eijerink

M w . dr. L.J.A. H assink-F ranke

Contents

Chapter 1

G eneral In tro d u c tio n

8

based on H uisarts W et. 2007;50(1):11-5

T he p a tien t

Chapter 2

C hronic fun ctio n al som atic sym ptom s: a single sy ndrom e?

26

B r J Gen Pract. 2004;54(509):922-7

Chapter 3

M edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s, so m atisatio n d iso rd er an d

42

h ypochondriasis: course a n d p rognosis. A system atic review

J Psychosom Res. 2009;66(5):363-77

Chapter 4

The d o cto r-p atien t relatio n sh ip fro m th e p ersp ectiv e of p atien ts

68

w ith p ersisten t m edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s. A n interview

stu d y

subm itted

T he doctor

Chapter 5

E xplanation an d relations. H ow do g eneral p ractitio n ers deal

86

w ith p atien ts w ith p ersisten t m edically u n ex p lain ed sym ptom s:

a focus g ro u p stu d y

B M C Fam Pract. 2009;10:68

T he co n su lta tio n

Chapter 6

'W ell doctor, it is all a b o u t h o w life is lived': cues as a tool in

106

th e m edical co n sultatio n

M e n t H ealth Fam M ed. 2008;5:183-7

Chapter 7

H ow p atien ts an d fam ily p h y sician s co m m u n icate ab o u t

p ersisten t m edically u n ex p lain e d sym ptom s. A q u alitativ e

stu d y of v ideo -reco rd ed co n su ltatio n s

P atient Educ Couns. 2011; A p r 7. [Epub ahead o f print]

116

S tartin g p o in ts for im p r o v in g m an a g em en t

Chapter 8

E xperts' opin io n s o n th e m a n ag em en t of m edically u n ex p lain e d

136

sym p to m s in p rim a ry care. A q u alitativ e analysis of n arrativ e

review s a n d scientific ed itorials

Fam Pract. 2011;28(4):444-455

Chapter 9

E xplanatory m odels of m edically u n ex p lain e d sym ptom s: a

162

qualitative analysis of the literatu re

M e n t H ealth Fam M ed. 2010;7:223-31

Chapter 10

M edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s in fam ily m edicine: d efin in g

180

a research agenda. P roceedings fro m W O N C A 2007

Fam Pract. 2008;25(4):266-71

Chapter 11

G eneral D iscussion

196

Summary / Samenvatting

218

Dankwoord

234

List of publications

242

Curriculum Vitae

252

10 I Chapter 1

M edicine is n o t o nly a science; it is also an art. I t does n o t consist o f com pounding pills and plasters; it

deals w ith the very processes o f life, w hich m u st be understood before they m ay be guided. (Paracelsus (c.

1493-1541))

General introduction | 11

Background

P hysical sy m p to m s su ch as h eadach e, back pain , dizzin ess a n d fatig u e are com m o n in the

general p o p u latio n . Tw o th ird s of m en a n d fo u r fifth of w o m en re p o rt a t least on e physical

sy m p to m in th e last tw o w eeks.1;2H o w ev er m o st p eo p le do n o t contact pro fessio n al m edical care

for these sy m p to m s.3;4W hen peo p le contact th eir G eneral P ractitio n er (GP) for th ese sy m p to m s

80% rem a in restricted to one d o cto r-p atien t contact,5 su g g estin g th a t m o st of these sy m p to m s

are transient.

In ab o u t 25-50% of all sym p to m s p rese n ted in p rim a ry h ea lth care, no evidence can be fo u n d for

an u n d e rly in g physical disease, an d sh o u ld be co n sid ered as m edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s

(MUS).6;7 In specialist care these p ercen tag es are ev en higher, ra n g in g fro m 30-70%.8;9 MUS

u su ally d isa p p ea r sp o n ta n eo u sly in th e course of tim e or as a consequence of th e p hysician's

m anagem ent. A recent D u tch s tu d y fo u n d th a t o nly 2.5% of th e p atien ts in g eneral practice

p rese n tin g w ith m edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s m eet criteria for ch ronicity.“ H o w ev er, this

m inority rep rese n t a maj or p ro b lem in h ea lth care for th e fo llo w in g reasons:

a. p atien ts w ith persisten t MUS suffer fro m th eir sy m p to m s, are fu n ctio n ally im p aired , a n d

are at risk for poten tially h arm fu l a d d itio n a l te stin g a n d treatm ent;

b. these p atien ts are a b u rd e n for th e h ea lth care sy stem as th ey are resp o n sib le for high,

often unnecessary, h ea lth care costs;

c. p atien ts w ith persisten t MUS are often d issatisfied w ith th e m edical care th ey receive

d u rin g th eir illness;

d. these p atien ts often cause feelings of fru stra tio n an d irritatio n in th eir physicians; an d

e. th e suitability, applicability a n d effectiveness of specific in te rv en tio n s to w ard s p atien ts

w ith persisten t MUS in p rim a ry care are lim ited.

The p roblem s described above are at the basis of the stu d ies re p o rte d in th is thesis, w h ich

to g eth er aim ed at g aining m ore in sig h t into th e care p atien ts w ith p ersis ten t MUS expect

(the patient), th e w ay G Ps experience th e care th ey d eliv er for th ese p atien ts (the doctor) a n d the

care G Ps deliver d u rin g en co u n ters w ith these p atien ts (the consultation) in o rd er to g u id e n ew

in te rv en tio n strategies for these patients.

Confusing terms

D efinitions in literature

In the scientific literatu re there is d iscu ssio n a n d d ebate for the b est te rm to describe physical

com plaints of p atien ts w h e n the aetiology is unclear. L ipow ski d efin ed som atisation as the

tendency to experience a n d com m unicate psychological d istress in the fo rm of som atic

1

12 I Chapter 1

sym p to m s th a t th e p a tie n t m isin te rp rets as signifying serio u s physical illness.11 In DSM-IV

som atisation disorder is defin ed as a histo ry of m an y ph y sical co m p lain ts (four p a in sym ptom s,

tw o g astro in testin al sym ptom s, one sexual sy m p to m a n d one p seu d o n eu ro -lo g ical sym ptom )

b eg in n in g before th e age of 30 th a t occur o ver a p erio d of sev eral years. E scobar in tro d u c e d the

concept of abridged som atisation, a con stru ct for less severe fo rm s of so m atisatio n ch aracterized

by fo u r or m ore u n ex p lain e d physical sy m p to m s in m en an d six or m o re u n ex p lain e d physical

sym p to m s in w om en.12 In fu n ctio n a l som atic syndrom es a set of u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s is

clustered into a syndrom e. In th is w ay each m edical specialty h as his o w n fu n ctio n al som atic

syndrom e. For exam ple C hronic F atigue S y n d ro m e (CFS) in in tern al m edicine, Irritable Bowel

S y ndrom e (IBS) in g astroenterology an d F ibrom yalgia (FM) in rh eu m ato lo g y . In N ijm egen the

te rm chronic nervous fu n ctio n a l somatic sym ptom s h as b een d ev elo p ed .13 P atien ts m eet this

diagnostic category w h e n th ey rep e ate d ly p rese n t ph y sical sy m p to m s th a t rem a in m edically

u n ex p lain e d after ad e q u ate exam ination, in co m b in atio n w ith th e (presu m ed ) presen ce of

psychosocial p roblem s or psychological distress. This d iagnostic category has b ee n in c lu d ed in

th e C o n tin u o u s M orbidity R egistry (CMR) sy stem w h ich w as in tro d u c ed by th e N ijm egen

D ep a rtm en t of Fam ily M edicine in 1971.13-16T o o u r k n o w led g e, th e CM R is th e only classification

system w ith a se p arate category for p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS. In a fu rth e r elab o ratio n of

chronic n erv o u s-fu n ctio n al sym ptom s, th e th eo ry of 'som atic fixation' w as dev elo p ed . Somatic

fixa tio n is th e consequence of co n tin u o u s o n e-sid ed em p h asis on th e som atic aspects of

sy m p to m s a n d h ea lth p roblem s resu ltin g in p eo p le beco m in g m o re an d m o re e n tan g led in and

d e p e n d e n t of h ea lth care.17;18This th eo ry explicitly ack n o w led g es th e role of th e p h y sician in the

d ev elo p m en t of p ersisten t MUS.

Which term w ill w e use in this thesis?

A n u m b e r of term s a n d definition s are u se d for p ersisten t sy m p to m s w ith o u t obvious

pathology. Som atisation has b een criticized, as it su g g ests th a t ph y sical sy m p to m s o rig in ate from

psychosocial distress. F u rth erm o re th is te rm assu m es p ath o g en ic p rocesses a n d tendencies,

such as illness b eh av io u r, o n th e p a rt of th e p atien t, w ith o u t co n sid erin g at all th e role of the

physician.19 C oncerning fu n ctio n a l somatic syndrom es, research ers arg u e th a t th e existing

definitions of these in d iv id u a l sy n d ro m es are of lim ited v alu e because: (1) th e su b stan tial

overlap b etw e en the in d iv id u a l sy n d ro m es a n d (2) th e sim ilarities b etw een th e m o u tw eig h the

differences.20F u rtherm ore, th e re is som e co n fu sio n reg a rd in g its core concept as it m ay refer to a

fun ctio n al distu rb an ce of org an s or th e b ra in sy stem s or it m ay refer to th e fu n ctio n of sym p to m s

w ith in the fra m ew o rk of seco n d ary gain.21 This also ap p lies for th e te rm chronic nervousfu n ctio n a l som atic sym ptom s. It has b een criticized for su g g estin g (1) th e tran slatio n of m ental

distress into physical sym ptom s, (2) th e im p licatio n th a t p atien ts h o ld o n to som atic a ttrib u tio n

of sym ptom s, a n d (3) a 'function' of th e sy m p to m s in ex p ressin g psychological d istress.22

H ow ever, a lth o u g h doctors m ay th in k th e te rm 'functional' is pejorative, p atien ts do n ot

General introduction | 13

perceive it as such.23 The te rm p ersistent m edically unexplained sym ptom s h as g ain ed p o p u la rity

d u rin g recent y ears am o n g general p ractitio n ers. A lth o u g h it defines p atien t's sy m p to m s by

w h a t they are n ot, rath e r th a n b y w h a t th ey are, an d a lth o u g h it reflects dualistic th in k in g , this

te rm is p u re ly descriptive an d th e m o st n e u tra l as it does n o t in d icate an u n d erly in g causal

m echanism or in te rp re tatio n .24H ow ev er, it has n eg ativ e co n n o tatio n s for p atien ts.23

These v ario u s term s a n d definitions reflect th e d ifficulties in th e concept of u n ex p lain e d bodily

com plaints w h ich is n o t u n equivocally d efined.25 A s a consequence of co n cep tu al problem s

d o cto r-p atien t com m unication a n d sy m p to m ex p lan atio n d u rin g co n su ltatio n is h am p ered .23

F urth erm o re, it com plicates research in th is p o p u la tio n as a a p p ro p ria te selection of th e stu d y

p o p u la tio n , a accurate definition of reference sta n d a rd s a n d a u sefu l d efin itio n of outcom e

m e asu res are lacking.26

In the light of the foregoing, w e d ecid ed to use th e te rm persisten t m edically unexplained sym ptom s

(p ersistent MUS) in this thesis, because w e th in k th is is th e m o st n e u tra l te rm a n d because this

te rm is w id ely accepted in to d a y 's scientific co m m u n ity a n d in p rim a ry ca re.

The patient, the doctor and the consultation

In 1979 researchers of the d e p a rtm e n t of Fam ily M edicine of th e R ad b o u d U n iv ersity N ijm egen

M edical C entre in th e N eth e rlan d s sta rte d a stu d y of som atic fixation.17This stu d y cu lm in ated in

th e book ' To heal or to harm. The prevention o f somatic fixa tio n in general practice' by R ichard G rol et

al.18 The concept of som atic fixation co nnected a th eo ry of h ea lth a n d illness w ith c o n su ltatio n

skills. Som atic fixation assum es a ten d en cy w ith in p atien ts to p ersisten tly experience

sym ptom s, freq u en tly as a consequence of psychological problem s. P atien ts w h o are inclined

to w ard s som atic fixation also te n d to in a d eq u a te h elp seeking b eh a v io u r a n d d ep en d en ce on

h ea lth care professionals. The re su lt of th ese ten d en cies is th a t th e p a tie n t focuses o n his or her

b o d y an d denies the relatio n b etw e en b o d ily sy m p to m s a n d psychosocial problem s.

A ccording to th a t theory, th e G P has p o w erfu l tools to p re v e n t som atic fixation an d w ith it

p ersisten t MUS. These tools - co n su ltatio n an d co m m u n icatio n skills - com p rise a goal-oriented

a n d system atic ap p ro ach , effective m a n ag em en t of th e d o cto r-p atien t relatio n sh ip an d

ad e q u ate tre a tm e n t of b o th som atic a n d psychosocial sy m p to m s. H o w ev er, d esp ite th e u se of

these tools, a sm all gro u p of p atien ts en d s u p w ith p ersisten t MUS. R esearch o n th e m an ag em en t

by G Ps of those functionally im p a ired an d su fferin g p atien ts an d reg a rd in g th e care these

p atien ts expect is still lim ite d .

14 I Chapter 1

E laborating o n the theory of som atic fixation a n d th e role of th e p atien t, th e d octor an d the

co n su ltatio n w e w ill (1) explore the k n o w led g e reg a rd in g th e p ro b lem s arisin g w h e n G Ps m eet

p atien ts w h o have d evelo p ed p ersisten t MUS in daily practice, a n d (2) in d icate k n o w led g e gaps

reg a rd in g the care G Ps deliver a n d the care p atien ts expect w h e n en c o u n te rin g w ith p ersisten t

MUS.

The patient

P atients w ith p ersisten t MUS often h av e the feeling th a t doctors do n o t ackn o w led g e the

legitim acy of th eir sym ptom s, a n d th a t th ey co n stan tly h av e to o p p o se th eir doctor's

skepticism .27 M any p atien ts feel th a t th eir doctors label th em as 'psychological cases'.28;29

F u rtherm ore, p atien ts have th e feeling th a t G Ps d o n 't take th e m serio u sly because G Ps o ften tell

th e m 'it is n o th in g ' or 'you do n o t have a disease'.27;30'33

P atients w ith distin ct fun ctio n al sy n d ro m es are o ften dissatisfied w ith the m edical care th ey

receive d u rin g their illness.28;34 They sense th e n ee d to fig h t to gain reco g n itio n a n d acceptance

fro m th e ir GP. O ften, these p atien ts co n sid er th eir d octor in co m p eten t an d them selv es as

experts reg a rd in g their o w n sym ptom s.35P atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS u se strateg ies to keep u p

m edical atten tio n w h e n they m eet an atm o sp h ere of d istru st in the co nsultation. These include

so m atizin g (i.e. p ersistin g in b odily explanations), claim ing u n d e r cover (i.e. referrin g to other

au th o rities such as TV or a n eig h b o u r w h o is a doctor), an d p le ad in g (crying a n d begging) to

catch th e d octor's interest.32;36

Which care do patients with persistent MUS expect?

The freq u en tly ex pressed dissatisfactio n by p atien ts w ith th e m edical care received d u rin g

illness m ig h t o rig in ate fro m the m ism atch b etw e en w h a t p atien ts w a n t a n d w h a t th ey actually

receive fro m their GP. A nalysis of v id e o ta p e d co n su ltatio n s sh o w ed th is m ism atch clearly

d u rin g th e initial p rese n tatio n of MUS in p rim a ry care. Salm on et al. sh o w ed th a t p atien ts w ith

MUS w ish to have a convincing, legitim atin g a n d e m p o w erin g ex p lan atio n for th eir sym p to m s

w hich, u n fo rtu n a te ly , is n o t given by th e ir GP.37-40 F u rth erm o re th ey in d icated th a t th ey w a n t

m ore em otional s u p p o rt fro m th eir G P.30 H o w ev er, research to w ard s preferen ces of p atien ts

w ith persisten t MUS reg a rd in g th e care th ey expect a n d receive in p rim a ry care is still lacking.

The doctor

R esearch p o in te d o u t th a t d octors o ften experience p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS as difficult to

m anage.27;41 F urth erm o re, th ey indicate th a t effective m a n ag em en t strateg ies are lacking.42 In

fact, m a n y GPs th in k th a t p ersisten t MUS are asso ciated w ith p erso n ality or psychiatric

diso rd ers.4443 F u rtherm ore, m an y doctors re g a rd p ersisten t MUS as a n ex p ressio n of

psychological distress w ith p atien ts failing to see th e co n n ectio n b etw e en th e physical

General introduction | 15

sym p to m s a n d the psychological distress.'41;44 A ccording to m an y G Ps, th e physical sy m p to m s

are n o t the real problem .44In ad d itio n , m an y d octors rem a in skeptical ab o u t ph y sical sy m p to m s

th a t can n o t be explained b y a physical disease.45 C o m p ared w ith p atien ts w ith 'real' diseases,

p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS do n o t h av e m u c h p restig e in th e m edical arena.46 In fact, research

has sh o w n th a t doctors' ju d g m e n ts re g a rd in g th e in ten sity of p ain felt by p atien ts is associated

w ith th e presence o r absence of su p p o rtin g m edical evidence.47W h en th e re is objective m edical

evidence for th e pain, doctors w ere m o re inclined to accept th e p atien t's claim reg a rd in g th e p ain

intensity. F urth erm o re, doctors te n d to believe th a t th ere is inco n g ru en ce b etw een the

p rese n tatio n of MUS a n d th e actual b u rd e n in th is case.45

W h en facing p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS, m an y G Ps feel p re ssu riz e d to offer som atic

interv en tio n s.44148This feeling of b ein g p re ssu riz e d has b een w id ely a ttrib u te d to p atien ts' belief

th a t sy m p to m s are cau sed by physical disease a n d to th eir rejection of psychological help .42;49

In conclusion, G Ps' subjective feelings of b ein g p ressu riz ed for som atic in te rv en tio n s as w ell as

G Ps' skepticism reg a rd in g p ersisten t MUS h elp s to ex p lain th eir d issatisfaction w ith

con su ltatio n s w ith p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS an d th e w id e sp re a d labelling of th em as

'heartsink' or 'difficult' patien ts.42;50-53 H o w ev er, d esp ite th is fru stra tio n a n d skepticism , m any

G Ps believe th a t p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS sh o u ld be m a n ag e d in p rim a ry care as p ro v id in g

reassurance, counselling a n d acting as a 'gatekeeper' to p re v e n t in a p p ro p ria te in v estig atio n s are

c o n sid ered im p o rta n t roles for G P m an ag em en t.42

How do GPs experience the care they deliver fo r these patients ?

A s can be expected fro m the afo rem en tio n ed difficulties w ith p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS, GPs

experience difficulties in th e ir m a n ag em en t of these p atien ts. P rev io u s stu d ies rev ealed th a t

these difficulties are m ainly associated w ith th e co m m u n icatio n a n d th e d o cto r-p atien t

relatio n sh ip w ith these p atien ts.27;45;54-59H o w ev er, m o st stu d ies d id n o t focus specifically o n GPs'

experiences of th e care th ey d eliver to p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS. A s p atien ts w ith p ersisten t

MUS w ill keep atte n d in g th e consu ltin g h o u rs of th eir G Ps w ith th eir sy m p to m s, G Ps h av e to

fin d strategies to specifically deal w ith th e co m m u n icatio n a n d th e d o cto r-p atien t relatio n sh ip

d u rin g th e enco u n ters w ith these chronic p atien ts. U n fo rtu n ately , h o w ev er, k n o w led g e ab o u t

these strategies an d G Ps ' experiences, w h ich are b u ilt o ver tim e d u rin g th e co n tin u in g pro cess of

GPs' h ea lth care delivery for these patien ts, is still lacking.

The consultation

A n u m b e r of stu d ies reg a rd in g the d o cto r-p atien t co m m u n icatio n d u rin g co n su ltatio n s w ith

MUS p atien ts h ave b een p u b lish ed .38* 61The resu lts of these stu d ies are im p o rta n t because th ey

d em o n strate th a t G Ps com m unicate w ith MUS p atien ts m ore p o o rly th a n p rev io u sly th o u g h t.

^

16 I Chapter 1

In contrast to con su ltatio n s w ith p atien ts w ith ex p lain ed sy m p to m s, G Ps d id explore the

sym ptom s, feelings, concerns, o pinio n s an d expectations of th e p a tie n t less ad eq u ately in

consultations w ith p atien ts w ith MUS. It seem s th a t th e d o cto r-p atien t co m m u n icatio n in

p atien ts w ith MUS is less p atien t-c en tred co m p ared to p atien ts w ith ex p lain ed sym ptom s.

A lth o u g h p atien t-c en tred com m unicatio n is of m ajor im p o rtan ce, th e resu lts d em o n strate d th at

doctors co m m unicated in a d eq u a tely in precisely those co n su ltatio n s w h ere p atien t-cen tred

com m unication is m o st d esired a n d ad v a n ta g eo u s.38

These stu d ies also sh o w ed th a t p atien ts w ith MUS d id n o t req u e st som atic in te rv en tio n s m ore

fre q u en tly th a n p atien ts w ith m edically ex p lain ed sym ptom s. A d d itio n ally , p atien ts w ith MUS

d id n o t ask for an ex p lan atio n or req u ire reassu ran ce m o re often th a n p atien ts w ith m edically

ex plained sym ptom s. These fin d in g s refu te th e GPs' subjective feeling of b ein g p ressu rized . The

only difference b etw e en p atien ts w ith ex p lain ed sy m p to m s a n d p atien ts w ith u n ex p lain e d

sy m p to m s w as th a t p atien ts w ith MUS d esired m o re em otional s u p p o rt fro m th e ir G P.60

H ow ever, G Ps w ere less em pathic to w a rd th ese patien ts. F u rth erm o re, in co n su ltatio n s w ith

patien ts w ith MUS, G Ps are m ore inclined to offer a p resc rip tio n th a n th a t p atien ts ask ed for a

presc rip tio n them selves (70% v ersu s 58%). Sim ilar resu lts w ere fo u n d w ith resp ect to p ro p o sals

for ad d itio n a l tests (35% v ersu s 13%) a n d su g g estio n s for referrals (20% v ersu s 14%).

D u rin g m o st consultations (m ore th a n 95%) w ith p atien ts w ith MUS, p atien ts in d ic ated one or

m ore psychosocial problem s. F urth erm o re they su g g e sted th a t the problem (s) m ay cause or

influence th eir sym ptom s. H ow ever, m o st G Ps do n o t seem to resp o n d to these cues.62;63

What care do GPs deliver during encounters with patients with persistent MUS ?

D octor-patient com m u n icatio n in p atien ts w ith MUS is a com plex p h en o m en o n . M ost stu d ies

described above stu d ie d th e d o cto r-p atien t in teractio n d u rin g th e initial p rese n tatio n of MUS

an d d id n o t focus o n p atien ts w ith persisten t MUS.38;60-61 H o w ev er, in g eneral m o st of th e tim e

MUS are tran sien t a n d im prove w ith o u t fu rth e r in te rv en tio n s after one or tw o consultations.

W hen sy m p to m s evolve into a chronic a n d d isab lin g co n d itio n (i.e. persisten t MUS), encounters

as w ell as d o cto r-p atien t com m unicatio n becom e m ore com plicated. H o w ev er, k n o w led g e of

th e d o cto r-p atien t com m u n icatio n in p atien ts w ith p ersistent MUS is still lacking.

Rationale for this thesis

As d escribed above, there is alread y su b stan tial k n o w led g e re g a rd in g the problem atic

interactio n w h e n G Ps m eet p atien ts d u rin g th e p rese n tatio n of MUS. H o w ev er m ost of this

research d id n o t focus specifically o n p a tie n t w ith persisten t MUS. The initial p rese n tatio n of

General introduction | 17

MUS does n o t rep rese n t a large p ro b lem for h ea lth care, as m ost of th ese sy m p to m s are tran sien t

an d have a good prognosis. The m ain p ro b lem w ith MUS p atien ts rises w h e n th ese sy m p to m s

develop to w ard s a chronic co n d itio n in w h ich p atien ts p ersisten tly p rese n t MUS to th eir GP.

From this p o in t o n th e G P has to fin d a w ay to m an ag e these p atien ts in o rd er to im p ro v e

patien ts' subjective w ell-being, sy m p to m red u c tio n a n d q u ality of life, to p re v e n t p o ten tial

h arm fu l investigations a n d referrals, a n d to p re v e n t G Ps o w n dissatisfactio n a n d fru stra tio n

•l1 these

l1

L* L 7;38;64;65

w ith

patients.

To im prove th e q u ality of care for p atien ts w ith persisten t MUS, w e n ee d in sig h t in to th e care G Ps

deliver an d the care p atien ts expect. This w ill lead to a b etter u n d e rs ta n d in g of strateg ies for the

m a n ag e m en t of p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS by GPs. F u rth erm o re, giv en th e lim ited

suitability, applicability a n d effectiveness of specific in te rv en tio n s in p rim a ry care (such as a n ti­

d ep ressan ts, cognitive b eh av io u ral th e ra p y a n d re a ttrib u tio n th erap y ) for p atien ts w ith

p ersiste n t M US,66-70 k n o w le d g e

of p a tie n ts o p in io n s, G Ps' v ie w s a n d d o c to r-p a tie n t

com m unication m ig h t gu id e n ew in te rv en tio n strateg ies for p atien ts w ith persisten t MUS in

p rim a ry care a n d enhance th e satisfactio n of G Ps as w ell as p atien ts w h ile en c o u n te rin g daily GP

practice.

Objectives of this thesis

T he aim of th is thesis w as to o b ta in m o re in sig h t in w h a t h ap p e n s w h e n G Ps en c o u n ter p atien ts

w ith persisten t MUS a n d w h ic h p roblem s th e n arise. Specifically w e w ere in te reste d in th e care

G Ps d eliver a n d th e care p atien ts expect w h e n v isitin g th e G P w ith persisten t MUS. T herefore, w e

d esig n ed a s tu d y to ev alu ate the three essential p a rts in th e care for th ese p atients: th e p atient,

th e doctor a n d th e consultation.

R eg ard in g the p a tien t w e aim ed to an sw er th e fo llo w in g research questions:

1. W h at are the characteristics of p atien ts w h o p rese n t p ersisten t MUS in p rim a ry care?

2. W h at is the course of MUS a n d w h ich facto rs influence its course?

3. W h at are patien ts' opin io n s ab o u t en co u n ters in w h ich th ey p rese n t p ersisten t MUS?

R eg ard in g the doctor w e aim ed to an sw er the fo llo w in g research questions:

1. W h at are G Ps' p ercep tio n s ab o u t en co u n ters w ith p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS?

R eg ard in g their consultations w e aim ed to an sw er th e fo llo w in g research questions:

1. H ow do G Ps talk to p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS d u rin g en co u n ters in w h ich p atien ts

p rese n t p ersisten t MUS?

18 I Chapter 1

W e fu rth e rm o re s tu d ie d th e literatu re aim in g to fin d sta rtin g p oints fo r im proving the m anagem ent

of p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS. W e th erefo re aim ed to an sw er th e fo llo w in g research

questions:

1. W hat are, according to experts in th e field, im p o rta n t a n d effective elem ents in the

trea tm e n t of MUS in p rim a ry care?

2. W hich explan ato ry m odels for MUS are describ ed in th e literatu re?

Outline of this thesis

The patient

In C h ap ter 2 w e p rese n t d ata ab o u t co m orbidity, referrals, d iagnostic tests, a n d h o sp ital

ad m issions over a p erio d of 10 y ears p rio r to th e diag n o sis chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s

in fo u r general practices p articip a tin g in th e C o n tin u o u s M o rb id ity R egistry (CMR) of the

u n iv ersity of N ijm egen.

C h ap ter 3 contains a system atic review a n d best-ev id en ce sy n th esis of th e literatu re on the

course of MUS, so m atisatio n diso rd er, h y p o ch o n d riasis, a n d rela ted p ro g n o stic factors.

C h ap ter 4 includes patien ts' opin io n s ab o u t en co u n ters in w h ich th ey p rese n t p ersisten t MUS.

A s w e consider the d o cto r-p atien t relatio n sh ip as a key factor in th e m a n ag em en t of p atien ts

w ith p ersisten t MUS, w e specifically ex p lo red p atien ts' o p in io n s ab o u t th e d o cto r-p atien t

relationship.

The doctor

C h ap ter 5 describes GPs' percep tio n s a b o u t en co u n ters w ith p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS. W e

focused o n percep tio n s a b o u t explain in g MUS to p atien ts a n d G Ps' p ercep tio n s ab o u t how

relatio n sh ip s w ith these p atien ts evolve o ver tim e in daily practice.

The consultation

C h ap ter 6 describes a co n su ltatio n w ith a p a tie n t w ith u n ex p lain e d p alp ita tio n s d u rin g

v a c u u m in g w hich ch an g ed m y perso n al co m m u n icatio n skills d u rin g en co u n ters w ith p atien ts

w ith p ersisten t MUS.

C h ap ter 7 p ro v id es insig h ts in how G Ps talk to p atien ts w ith p ersisten t MUS d u rin g th eir

encounters. W e focused p rim a rily on G Ps' ex p lo ratio n of p atien ts' sy m p to m s an d p ro b lem s and

G Ps d istrib u tio n of th e available tim e o n d ifferen t stages in th e p ersisten t MUS consultations.

Starting points for improving the management

In C h ap ter 8 w e p rese n t th e resu lts of a q u alitativ e analysis of n arrativ e rev iew s an d scientific

edito rials to explore experts opin io n s reg a rd in g effective m a n ag em en t strateg ies for p atien ts

w ith MUS.

General introduction | 19

C h ap ter 9 p ro v id es an overview of ex p lan ato ry m odels (i.e. m o d els of ex p lain in g th e n a tu re of

th e sym ptom s) of MUS described in th e scientific literatu re th a t m ay be of u se in daily general

practice.

C h ap ter 10 contains th e resu lts of a sy m p o siu m a n d w o rk sh o p o n MUS in p rim a ry care h eld a t

th e W onca W orld C onference 2007 in S ingapore. D u rin g th is m eetin g w e fo cu sed o n detecting

k n o w ledge g aps in MUS a n d establish in g p rio rities in MUS research.

In C h ap ter 11 th e resu lts of this thesis are critically rev iew ed , a n d reco m m en d atio n s for clinical

practice, m edical ed u c atio n an d fu tu re research are given.

1

20 I Chapter 1

Reference List

1

H o u tv ee n JH. D e d o k ter k an n iets v in d en . A m sterdam : U itgeverij B ert Bakker; 2009.

2

K roenke K, S pitzer RL. G en d er differences in th e rep o rtin g of physical a n d so m ato fo rm

3

G reen LA, F ryer GE, Jr., Y aw n BP, L anier D, D ovey SM. The ecology of m edical care

4

v a n de L isdonk EH. E rvaren en aan g eb o d e n m o rb id iteit in de h u isartsp rak tijk . Thesis.

sym ptom s. P sychosom M ed 1998; 60(2):150-155.

revisited. N Engl J M ed 2001; 344(26):2021-2025.

N ijm egen: K atholieke U n iversiteit N ijm egen, 1985.

5

v a n d er L inden M, W estert G, de Bakker D, Schellevis F. T w eede N atio n ale S tu d ie n aa r

ziekten en v errich tin g en in de h u isartsp rak tijk : k lach ten en a a n d o en in g en in de b ev o lk in g

en in de h u isa rtsp ra k tijk (Second N atio n al S urvey of m o rb id ity a n d in te rv en tio n s in general

practice: sy m p to m s a n d diseases in th e p o p u la tio n ). 2004.

Ref Type: R eport

6

P eveler R, K ilkenny L, K inm on th AL. M edically u n ex p lain e d ph y sical sy m p to m s in

p rim a ry care: a co m p ariso n of self-rep o rt screen in g q u estio n n aires an d clinical op in io n . J

Psychosom Res 1997; 42(3):245-252.

7

Barsky AJ, Borus JF. S om atizatio n a n d m ed icalizatio n in th e era of m a n ag e d care. JAMA

1995; 274(24):1931-1934.

8

N im n u a n C, H o to p f M, W essely S. M edically u n ex p lain e d sym ptom s: an epidem iological

stu d y in seven specialities. J P sychosom Res 2001; 51 (1):361-367.

9

Reid S, W essely S, C rayford T, H o to p f M. M edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s in fre q u en t

a tten d e rs of secondary h ea lth care: retro sp ectiv e co h o rt stu d y . BMJ 2001; 322(7289):767.

10 V erhaak PF, M eijer SA, V isser AP, W olters G. P ersisten t p rese n tatio n of m edically

u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s in general practice. Fam P ract 2006; 23(4):414-420.

11 L ipow ski ZJ. S om atization: the concept an d its clinical ap plication. A m J P sy ch iatry 1988;

145(11):1358-1368.

12 E scobar JI, G old in g JM, H o u g h RL, K arno M, B urnam M A, W ells KB. S o m atizatio n in the

com m unity: relatio n sh ip to disability an d u se of services. A m J Public H ea lth 1987;

77(7):837-840.

13 v a n W eel-B aum garten EM. D epression: th e lo n g -term perspective. A fo llo w -u p s tu d y in

general practice. Thesis. N ijm egen: R ad b o u d U n iv ersity N ijm egen M edical C entre, 2000.

14 v a n W eel C. V alid atin g long te rm m o rb id ity recording. J E pidem iol C o m m u n ity H ealth

1995; 49 S u p p l 1:29-32.

15 v a n W eel C, de G rau w WJ. Fam ily practices reg istra tio n n etw o rk s co n trib u ted to p rim a ry

care research. J C lin E pidem iol 2006; 59(8):779-783.

16 v a n W eel C. The C o n tin u o u s M orb id ity R eg istratio n N ijm egen: b ac k g ro u n d a n d h isto ry of a

D u tch general practice database. E ur J G en P ract 2008; 14 S u p p l 1:5-12.:5-12.

General introduction | 21

17 v an Eijk JT, G rol R, H u y g en FJ, M esker P, M esker-N iesten J, v a n M ierlo G et al. The fam ily

doctor a n d the p rev e n tio n of som atic fixation. Fam ily System s M edicine 1983;

1:5-15.

18 G rol R. To heal or to harm . The p rev e n tio n of som atic fix atio n in G eneral Practice. L ondon:

Royal College of G eneral P ractitioners; 1981.

19 K irm ayer LJ, Robbins JM. T hree form s of so m atizatio n in p rim a ry care: p revalence, co­

occurrence, a n d sociodem ograph ic characteristics. J N erv M ent Dis 1991;

179(11):647-655.

20 W essely S, N im n u a n C, S harpe M. F unctional som atic syndrom es: one or m any? L ancet

1999; 354(9182) :936-939.

21

C reed F, G u th rie E, Fink P, H en n in g sen P, Rief W , S h arp e M et al. Is th e re a b etter te rm th a n

"m edically u n ex p lain e d sym ptom s"? J P sychosom Res 2010; 68(1):5-8.

22 de W aal MW , A rnold IA. S om atoform d iso rd ers in g eneral practice. E pidem iology,

tre a tm e n t a n d com orbidity w ith d ep ressio n a n d anxiety. Thesis. L eiden: U niversiteit

L eiden, 2006.

23 Stone J, W ojcik W, D urran ce D, C arso n A, L ew is S, M acK enzie L et al. W h at sh o u ld w e say to

p atien ts w ith sym p to m s u n ex p lain e d by disease? The "num ber n e e d e d to offend". BMJ

2002; 325 (7378):1449-1450.

24 de W aal MW , A rn o ld IA, E ekhof JA, v a n H em ert AM. S om atoform d iso rd ers in general

practice: prevalence, fun ctio n al im p a irm en t a n d co m o rb id ity w ith anxiety a n d d ep ressiv e

disorders. Br J P sychiatry 2004; 184:470-6.:470-476.

25 v a n B okhoven MA. Blood test o rd erin g for u n ex p lain e d co m p lain ts in g eneral practice. The

feasibility of a w atch fu l w aitin g ap p ro ach . Thesis. M aastricht: M aastrich t U niversity, 2008.

26 v a n B okhoven MA, K och H , v a n d er WT, D in an t GJ. Special m eth o d o lo g ical challenges

w h e n s tu d y in g th e diagnosis of u n ex p lain e d co m p lain ts in p rim a ry care. J C lin E pidem iol

2008; 61(4):318-322.

27 M a lteru d K. S ym ptom s as a source of m edical know ledge: u n d e rs ta n d in g m edically

u n ex p lain e d d iso rd ers in w om en. F am M ed 2000; 32(9):603-611.

28 Page LA, W essely S. M edically u n ex p lain e d sym ptom s: exacerb atin g factors in th e doctorp a tie n t encounter. J R Soc M ed 2003; 96(5):223-227.

29 K ouyanou K, P ither CE, R abe-H esketh S, W essely S. A co m p arativ e s tu d y of iatrogenesis,

m ed icatio n abuse, a n d psychiatric m o rb id ity in chronic p a in p atien ts w ith a n d w ith o u t

m edically explained sym ptom s. P ain 1998; 76(3):417-426.

30 P eters S, S tanley I, Rose M, S alm on P. P atien ts w ith m edically u n ex p lain e d sym ptom s:

sources of p atien ts' a u th o rity a n d im plications for d em an d s o n m edical care. Soc Sci M ed

1998; 46(4-5):559-565.

31 S alm on P, P eters S, S tanley I. P atien ts' p ercep tio n s of m edical ex p lan atio n s for so m atisatio n

disorders: q u alitativ e analysis. BMJ 1999; 318(7180):372-376.

22 I Chapter 1

32 Johansson EE, H am b erg K, L in d g ren G, W estm an G. "I've b een crying m y w ay "--qualitative

analysis of a gro u p of fem ale patien ts' co n su ltatio n experiences. Fam P ract 1996; 13(6):498503.

33 N ettleto n S, W att I, O 'M alley L, D uffey P. U n d e rsta n d in g th e n arrativ es of p eo p le w h o live

w ith m edically u n ex p lain e d illness. P atien t E duc C o u n s 2005; 56(2):205-210.

34 D eale A, W essely S. P atients' percep tio n s of m edical care in chronic fatig u e sy n d ro m e. Soc

Sci M ed 2001; 52(12) :1859-1864.

35 S alm on P. P atients w h o p rese n t ph y sical sy m p to m s in th e absence of ph y sical pathology: a

challenge to existing m odels of d o cto r-p atien t interaction. P atien t E duc C o u n s 2000;

39(1):105-113.

36 W ern er A, M a lte ru d K. It is h a rd w o rk b eh a v in g as a credible patien t: en co u n ters b etw een

w o m en w ith chronic p a in a n d th e ir doctors. Soc Sci M ed 2003; 57(8):1409-1419.

37 Ring A, D ow rick C, H u m p h ris G, Salm on P. Do p atien ts w ith u n ex p lain e d physical

sy m p to m s p ressu rise g eneral p ractitio n ers for som atic treatm en t? A q u alitativ e stu d y . BMJ

2004; 328(7447):1057.

38 E pstein RM, S hields CG, M e ld ru m SC, Fiscella K, C arroll J, C arney PA et al. P hysicians'

responses to patien ts' m edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s. P sychosom M ed 2006; 68(2):269276.

39 D ow rick CF, R ing A, H u m p h ris GM , S alm on P. N o rm alisatio n of u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s

by general practitioners: a functio n al typology. Br J G en P ract 2004; 54(500):165-170.

40

Coia P, M orley S. M edical reassu ran ce a n d p atien ts' responses. J P sychosom Res 1998;

45(5):377-386.

41 W oivalin T, K rantz G, M a n ty ra n ta T, R ingsberg KC. M edically u n ex p lain e d sym ptom s:

percep tio n s of physicians in p rim a ry h ea lth care. F am P ract 2004; 21 (2) :199-203.

42 Reid S, W hooley D, C rayford T, H o to p f M. M edically u n ex p lain e d sym ptom s--G P s'

attitu d e s to w ard s their cause a n d m an ag em en t. F am P ract 2001; 18(5):519-523.

43 S harpe M, M ayou R, W alker J. Bodily sym ptom s: n ew ap p ro ach es to classification. J

P sychosom Res 2006; 60(4) :353-356.

44 W ilem an L, M ay C, C h ew -G raham CA. M edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s a n d th e p ro b lem

of p o w er in the p rim a ry care consultation: a q u alitativ e stu d y . F am P ract 2002; 19(2):178182.

45 A sbring P, N a rv a n e n AL. Ideal v ersu s reality: p h y sician s p ersp ectiv es o n p atien ts w ith

chronic fatig u e sy n d ro m e (CFS) an d fibrom yalgia. Soc Sci M ed 2003; 57(4):711-720.

46 A lbum D, W estin S. D o diseases h av e a p restig e hierarchy? A su rv ey am o n g p h y sician s an d

m edical stu d en ts. Soc Sci M ed 2008; 66(1):182-188.

47 Tait RC, C hibnall JT. P hysician ju d g m e n ts of chronic p a in patien ts. Soc Sci M ed 1997;

45(8):1199-1205.

General introduction | 23

48

A rm stro n g D, Fry J, A rm stro n g P. D octors' p ercep tio n s of p ressu re fro m p atien ts for

referral. BMJ 1991; 302(6786):1186-1188.

49 G o ld b erg DP, B ridges K. Som atic p rese n tatio n s of p sychiatric illness in p rim a ry care

setting. J P sychosom Res 1988; 32(2):137-144.

50 G arcia-C am payo J, S anz-C arrillo C, Yoldi-E lcid A, L opez-A ylon R, M o n to n C. M an ag em en t

of som atisers in p rim a ry care: are fam ily doctors m o tiv ated ? A u st N Z J P sy ch iatry 1998;

32(4):528-533.

51 H a rtz AJ, N oyes R, B entler SE, D am iano PC, W illard JC, M om any ET. U n ex p lain ed

sy m p to m s in p rim a ry care: p ersp ectiv es of d o cto rs a n d p atien ts. G en H o sp P sy ch iatry 2000;

22(3):144-152.

52 S teinm etz D, T abenkin H. The 'difficult p atien t' as p erceiv ed by fam ily physicians. Fam

P ract 2001; 18(5):495-500.

53 M athers N, Jones N , H an n a y D. H ea rtsin k p atients: a s tu d y of th eir g eneral p ractitio n ers. Br

J G en P ract 1995; 45(395):293-296.

54 W alker EA, U n u tze r J, K aton WJ. U n d e rsta n d in g a n d carin g for th e d istre ssed p a tie n t w ith

m u ltip le m edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s. J A m B oard Fam P ract 1998;

11(5):347-356.

55 Lin EH, K aton W , V on K orff M, B ush T, L ipscom b P, R usso J et al. F ru stra tin g patients:

physician a n d p a tie n t p erspectives am o n g d istressed h ig h u sers of m edical services. J G en

In tern M ed 1991; 6(3):241-246.

56 W alker EA, K aton WJ, K eegan D, G a rd n e r G, S ullivan M. P red icto rs of p h y sician fru stra tio n

in the care of p atien ts w ith rh eu m ato lo g ical com plaints. G en H o sp P sychiatry 1997;

19(5):315-323.

57 L u n d h C, S egesten K, B jorkelund C. To be a helpless helpoholic--G Ps' experiences of w o m en

p atien ts w ith non-specific m uscu lar pain. Scand J P rim H ea lth C are 2004; 22(4):244-247.

58 S m ith S. D ealing w ith the difficult p atien t. P o stg rad M ed J 1995; 71(841):653-657.

59 H a h n SR, T hom pson KS, W ills TA, S tern V, B u d n er NS. The difficult d o cto r-p atien t

relationship: so m atization, p erso n ality a n d psy ch o p ath o lo g y . J Clin E pidem iol 1994;

47(6):647-657.

60 S alm on P, Ring A, D ow rick CF, H u m p h ris GM. W h at do g eneral practice p atien ts w a n t

w h e n th ey p rese n t m edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s, an d w h y do th e ir doctors feel

p ressu rized ? J P sychosom Res 2005; 59(4):255-260.

61 Ring A, D ow rick CF, H u m p h ris GM , D avies J, S alm on P. The so m atisin g effect of clinical

consultation: W hat p atien ts a n d doctors say a n d do n o t say w h e n p atien ts p rese n t m edically

u n ex p lain e d physical sym ptom s. Soc Sci M ed 2005; 61 (7):1505-1515.

62 C egala DJ. A s tu d y of doctors' a n d p atien ts' co m m u n icatio n d u rin g a p rim a ry care

consultation: im plications for com m u n icatio n training. J H ea lth C o m m u n 1997;

2(3):169-194.

24 I Chapter 1

63 Salm on P, D ow rick CF, Ring A, H u m p h ris GM. V oiced b u t u n h e a rd agendas: q u alitativ e

analysis of the psychosocial cues th a t p atien ts w ith u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s p rese n t to

general p ractitioners. Br J G en P ract 2004; 54(500):171-176.

64 L ucassen P, olde H a rtm a n TC, B orghuis MS. Som atische fixatie. Een n ie u w lev en v o o r een

o u d begrip. H u isa rts en W etenschap 2007; 50(1):11-15.

65 S m ith GR, Jr., M onson RA, Ray DC. P atien ts w ith m u ltip le u n ex p lain e d sym ptom s. Their

characteristics, functional health , a n d h ea lth care u tilization. A rch In tern M ed 1986;

146(1):69-72.

66 K roenke K. Efficacy of tre a tm e n t for so m ato fo rm disorders: a rev iew of ran d o m ized

co ntrolled trials. P sychosom M ed 2007; 69(9):881-888.

67 S u m ath ip ala A. W hat is the ev idence for th e efficacy of trea tm e n ts for so m ato fo rm

disorders? A critical review of p rev io u s in te rv en tio n stu d ies. P sychosom M ed 2007;

69(9):889-900.

68 M orriss R, G ask L, D ow rick C, D u n n G, P eters S, R ing A et al. R an d o m ized trial of

rea ttrib u tio n o n psychosocial talk b etw e en d o cto rs an d p a tie n ts w ith m edically

u n ex p lain e d sym ptom s. P sychol M ed 2010; 40(2) :325-333.

69 M orriss R, D ow rick C, S alm on P, P eters S, D u n n G, R ogers A et al. C luster ran d o m ised

controlled trial of train in g practices in re a ttrib u tio n for m edically u n ex p lain e d sym ptom s.

Br J P sychiatry 2007; 191:536-42.:536-542.

70 M ultidisciplinary g uideline m edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s a n d so m ato fo rm d iso rd e rs].

T rim bos In s titu u t/N e th e rla n d s In stitu te of M ental H ea lth an d A d d ictio n , editor. 2009.

H o u ten , L adenius C om m unicatie BV.

Ref Type: R eport

General introduction | 25

28 I Chapter 2

Abstract

Background.

Reliable lo n g itu d in al d a ta of p atien ts w ith fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s in

g eneral practice are lacking.

Aim.

T o identify distinctive featu res in p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sym ptom s,

an d to determ in e w h e th e r these sy m p to m s su p p o rt th e h y p o th esis of th e existence of specific

som atic syndrom es.

Design.

O bservational stu d y , w ith a co m p ariso n co n tro l group.

Setting.

Four p rim a ry care practices affiliated w ith th e U n iv ersity of N ijm egen in The

N etherlands.

Methods.

O ne h u n d re d an d eig h ty -tw o p atien ts d ia g n o sed b etw e en 1998 a n d 2002 as

h av in g chronic fun ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s an d 182 controls m atch ed by age, sex,

socioeconom ic statu s, a n d practice w ere in clu d ed . D ata on co m orbidity, referrals, diagnostic

tests, a n d h o sp ital adm issio n s over a p erio d of 10 y ears p rio r to th e diag n o sis w ere collected.

M edication use a n d n u m b e r of visits to th e g eneral p ractitio n er (GP) w ere extracted fro m the

m o m en t co m p u teriz ed reg istratio n w as started.

Results.

In th e 10 y ears before th e d iag n o sis chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s,

significantly m ore p atien ts th a n controls p rese n t fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s in at least tw o

b o d y system s, a n d u se d m ore som atic a n d psy ch o tro p ic d ru g s. T hey v isit th e G P tw ice as m uch,

statistically h a d significantly m ore p sychiatric m o rb id ity , a n d w ere referred m o re often to

m ental h ea lth w o rk e rs a n d som atic specialists. The n u m b e r of p atien ts u n d e rg o in g diagnostic

tests w as higher for p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s th a n for controls, b u t

h o sp ital ad m issions rates w ere equal.

Conclusion.

P atients w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s h av e a g reat d iv ersity of

fun ctio n al som atic sym ptom s. They u se m o re som atic a n d p sy ch o tro p ic d ru g s th a n controls in

th e y ears before diagnosis. M oreover, th ey sh o w h ig h rates of referrals an d psychiatric

m orbidity. The div ersity of sym p to m s of p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s

su p p o rts th e concept th a t sym p to m s do n o t cluster in w ell-d efin ed d istin ct syndrom es.

T herefore, p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s sh o u ld p referab ly n o t be

classified into m edical su bspecialty syndrom es.

Chronic functional somatic symptoms: a single syndrome? | 29

Introduction

M edically u n ex p lain e d sym p to m s are com m on, a n d acco u n t for one in five n ew co n su ltatio n s in

p rim a ry care.1;2In 20-25% of all p rim a ry care visits, no serio u s m edical (that is, organic) cause is

fo u n d to ex p lain th e p atien t's p rese n tin g sy m p to m , an d 20-40% of th e p atien ts seen by m edical

specialists do n o t receive a clear diag n o sis.3;4 The p rese n ted sy m p to m s are th e n referred to as

'm edically unex p lain ed ' or 'functional'.5 F unctional, or rath e r m edically u n ex p lain ed , som atic

sym p to m s are ran k e d second o n th e list of th e 10 m o st com m on physical sy m p to m s in p rim ary

care an d have a n incidence rate of 70 p e r 1000 p a tie n t y ears in th e N e th e rla n d s.6

A lth o u g h an occasional v isit to the general p ractitio n er (GP) for a fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m

seem s n atu ra l, rep e ate d consultations because of these sy m p to m s rep rese n t a serio u s problem .

P atients w h o do this are often d iag n o sed as h av in g 'chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sym ptom s'.

Psychological d istress or psychosocial p ro b lem s are p re su m e d to b e th e u n d e rly in g cau ses.7As

such, diag n o sin g chronic fun ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s req u ires th e p a tie n t to rep eated ly

p rese n t physical sy m p to m s th a t rem a in m edically u n ex p lain e d after ad e q u ate exam ination,

an d indications, fro m the patien ts' p erso n al circum stances of p re su m e d psychosocial p roblem s

or psychological distress.

A s p atien ts w ith chronic functional som atic sy m p to m s are fu n ctio n ally im p aired , h av e h ig h

rates of com orbid psychiatric disorders, a n d are at risk of u n n ecessary d iagnostic p ro ced u res

an d treatm en ts, 1;4;<M1a correct d iagnosis is of p a ra m o u n t im p o rtan ce. H o w ev er, m o st research on

this topic has b ee n p erfo rm ed either o n u n selected p o p u la tio n -b ase d sam p les,12^3or in selected

patien ts referred to seco n d ary care.14;15 M oreover, m o st of th ese stu d ies m ake use of

q u estio n n aires in w h ich p atien ts h av e to recall a v arie ty of sy m p to m s ex istin g for a considerable

am o u n t of tim e.10;16;17This m e th o d has b een sh o w n to p ro d u ce u n stab le resu lts in w h ich lifetim e

sym p to m s p rese n t a t baseline are n o t rem em b ered a t fo llo w -u p .18 R esearch o n p atien ts from

p rim a ry care settings in w h o m th e diag n o sis h a d b een m ad e o n reliable lo n g itu d in al d ata is

generally lacking.

M oreover, th e re is considerable d ebate re g a rd in g th e q u estio n of w h eth e r fu n ctio n al som atic

sym p to m s cluster in w ell defin ed distin ct sy n d ro m es, su ch as fib rom yalgia, chronic fatig u e

syndrom e, or ten sio n headache, or w h eth e r th ese specific som atic sy n d ro m es are largely an

artefact of m edical sp ecilization.7;19In th is d ebate reliable d ata o n p rim a ry care p atien ts are also

n ee d ed , w h ereas m o st research on th is topic is p erfo rm ed in referred p o p u la tio n s2“21

concentrating o n specific sy m p to m s,22-24 or in co m m u n ity sa m p le s25 u sin g q u estio n n aires in

w h ich inconsistencies of recall m ay h av e a g reat effect o n th e assessm en t of th e u ltim ate

diagnosis.1826 The aim s of th is stu d y , therefore, are to explore w ith lo n g itu d in al data:

30 I Chapter 2

• h o w an d how often p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s p rese n t to their

G P a n d oth er m edical in stitution s,

• w h e th e r p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s in d e ed p rese n t m ore

functional som atic sy m p to m s in th e y ears before th e diagnosis,

• if sy m p to m s p rese n ted b y p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s su p p o rt

the existence of specific som atic syndrom es.

Methods

Continuous Morbidity Registration database

This s tu d y uses d ata fro m the C o n tin u o u s M o rb id ity R eg istratio n (CMR) d atab ase, a project of

th e d e p a rtm e n t of Fam ily M edicine of th e U n iv ersity of N ijm egen th e N eth e rlan d s.27-30 This

project w as sta rted in 1971 in fo u r practices in a n d a ro u n d N ijm egen31an d m o n ito rs a p o p u la tio n

of ap p ro x im ately 12 000 patien ts, rep rese n tativ e of th e D u tch p o p u la tio n w ith re g a rd to age an d

sex. E very episode of illness seen by, or re p o rte d to, th e G P is reg istered as so o n as it is

estab lish ed u sin g an ad a p te d v ersio n of th e E-list.32 D iagnoses an d codes are co rrected w h en

necessary. O ver m an y years, m o n th ly m eetin g s of all G Ps in v o lv ed are h eld to discuss

classification problem s, to m o n ito r th e a p p licatio n of d iagnostic criteria, a n d to discuss co ding

p roblem s of h y p o th etical case histories. As w ell as m edical d ata, th e fo llo w in g in fo rm atio n is

available: age, sex, socioeconom ic sta tu s (low, m id d le a n d high), a n d m arital statu s. In the

b eg in n in g th e reg istra tio n w as p erfo rm ed o n th e m edical chart; since 1994 a co m p u terized

reg istra tio n has b een used.

Patients with chronic functional somatic symptoms

W e selected all p atien ts fro m the CMR d atab ase in w h o m chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sym p to m s

w ere d iag n o sed for the first tim e b etw e en 1998 a n d 2002 (n = 182). For a p erio d of 10 y ears before

this diagnosis, th e follow ing variab les h ad b een collected: sociod em o g rap h ic characteristics;

m orb id ity data; a n d d a ta o n referrals, d iagnostic tests, a n d h o sp ital adm issions. U se of m edical

facilities w as assessed by the n u m b e r of contacts w ith th e GP. D ata on m ed icatio n use co u ld be

extracted fro m w h e n co m p u teriz ed reg istra tio n sta rted , a n d m ed icatio n d ata w ere tran sfo rm ed

in to th e p re sc rib e d

d a ily

d o se b y u sin g th e A n a to m ic a l T h e ra p e u tic a l C h em ical

C lassificatio n /D efin ed D aily D oses (A T C /D D D ) system .33As a pro x y of som atic m o rb id ity , w e

assessed three p rev a len t categories of chronic d iso rd ers (diabetes m ellitus, asth m a /c h ro n ic

obstru ctiv e p u lm o n a ry disease [COPD], an d card io v ascu lar diseases) a n d th ree p rev alen t

categories of self-lim iting d iso rd ers (skin d iso rd ers, m usculoskeletal, a n d airw ay) in o rd er to

stu d y th e h y p o th esis th a t p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s are at risk for

som atic m o rb id ity .37

Chronic functional somatic symptoms: a single syndrome? | 31

W e allocated the reg istered functional som atic sy m p to m s to specific b o d y system s; for exam ple,

g astro in testin al or m usculoskeletal, as described by E scobar et al.10 Irritab le b o w el sy n d ro m e

an d h y p erv e n tila tio n sy n d ro m e, som etim es re g a rd e d as m edically u n ex p lain e d sy m p to m s, are

n o t in c lu d ed in this study.

Controls

For each p a tie n t w ith chronic fun ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s, a control m atch ed b y age, sex,

socioeconom ic sta tu s, a n d practice w as d ra w n fro m th e CMR p o p u latio n . The o nly exclusion

criterion in th e control g ro u p w as the diag n o sis chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s. P atients

w h o w ere controls h a d to have h a d at least one reg istered ep iso d e of illness d u rin g th e p erio d

they h a d b een o n th e practice list. For controls, th e sam e in fo rm atio n as describ ed for p atien ts

w ith chronic fun ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s w as o b tain ed fro m 1990-2000.

Statistical methods

O u r analysis p rim arily in v o lv ed co m p arin g p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s

w ith th eir m atch ed controls. S tatistical analyses w ere co n d u cted u sin g SPSS 9.0. D escriptive

statistics w ere calculated for all variables. The d a ta o n specific b o d y sy stem s w ere an aly sed

u sin g explo rato ry factor analysis, a n d th e n sim p lified by v arim ax ro tation. The j 2 te st an d

stu d e n t's t-test w ere u se d for co m p arin g m eans of co n su ltatio n s an d m ed icatio n use in b o th

groups. O d d s ratio s (ORs) a n d 95% confidence in terv als (CIs) w ere u se d as th e m ain

m easu rem en t for associations, p articu larly w ith reg a rd to fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s,

com orbidity, referrals, diagnostic tests a n d h o sp ital adm issions. All P -values are tw o-tailed.

Results

Characteristics of subjects

O f the 182 in c lu d ed p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s in c lu d ed in th e stu d y ,

141 (77.5%) w ere w om en; th e m ean age of all p atien ts w as 42.0 y ears (range = 10-85 years). M ost

subjects w ere of low (44.5%) or m id d le (42.9%) socioeconom ic class.

Functional somatic symptoms

The incidence rate of p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s w as 3.5 p er 1000

p a tie n t years, w h ereas th e p revalence of p atien ts k n o w n to h av e chronic fu n ctio n al som atic

sym p to m s is established o n 68.8 p er 1000 p a tie n t years.

The p rese n ted fun ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s in v ario u s b o d y sy stem s in p atien ts a n d controls is

d isp lay ed in T able 1. For each sy m p to m g ro u p , p atien ts an d controls differ significantly

32 I Chapter 2

Table 1. Distribution of functional somatic symptoms in the various body systems (n = 182)

Pseu d o n eu ro lo g ical

Patients (%)

Controls (%)

Odds ratio (95% CI)‘

54 (29.7)

13 (7.1)

5.5 (2.8 to 11.1)

G astro in testin al

69 (37.9)

15 (8.2)

6.8 (3.6 to 13.1)

M usculoskeletal

58 (31.9)

6 (3.3)

13.7 (5.5 to 36.5)

C ard io resp irato ry

74 (40.7)

16 (8.8)

7.1 (3.8 to 13.5)

H ead ach e a n d o th er p a in

80 (44.0)

15 (8.2)

8.7 (4.6 to 16.6)

Pseu d o p sy ch iatric

150 (82.4)

48 (26.4)

13.1 (7.7 to 22.4)

O thers

66 (36.3)

10 (5.5)

9.8 (4.6 to 12.2)

U nknow n

67 (36.8)

0 (0)

aStatistical significant difference between patients and controls.

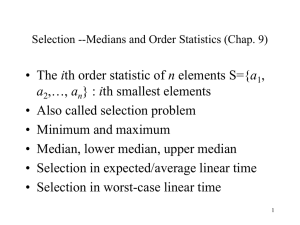

(P<0.05). It is rem arkable th a t m an y p atien ts h a d sy m p to m s in v ario u s b o d y sy stem s - a fin d in g

th a t is su p p o rte d by the factor analysis (Figure 1) - as it is often co n sid ered th a t th e re are a

n u m b e r of w ell-d efin ed distin ct fun ctio n al som atic sy n d ro m es, clu sterin g a ro u n d physical

sym p to m s of one b o d y system . M oreover, factor analysis su g g ests th at, o n th e one han d ,

gastrointestinal, ca rd io resp irato ry , a n d p seu d o p sy ch iatric sy m p to m s are lin k ed an d , o n the

Figure 1. Symptom diversity in patients with chronic functional somatic symptoms and their matched controls

controls

patients

number of affected body systems

Chronic functional somatic symptoms: a single syndrome? | 33

other, th a t pseu d o n eu ro lo g ical sym pto m s, m u scu lo sk eletal sy m p to m s, a n d h ead ach e a n d other

pain, are lin k ed w ith each other. S ignificantly m o re p atien ts th a n controls p rese n ted sy m p to m s

in tw o or m ore b o d y system s (87.9 v ersu s 19.8%; OR = 29.5, 95% CI = 16.0 to 54.9). O f all the

patien ts, 25 % p rese n ted sym p to m s in fo u r or m o re b o d y sy stem s.

H alf of th e p atien ts h a d th ree or m ore ep iso d es of fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s before he or she

w as d iag n o sed as h av in g chronic functio n al som atic sy m p to m s; 25% of th e p atien ts h ad five or

m ore episodes before chronic fun ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s w ere d iagnosed.

Comorbidity: somatic and psychiatric

P atients w ith chronic fun ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s h ad significantly m ore psychiatric

d iso rd ers in co m p ariso n w ith controls (OR = 2.4) (Table 2). P atien ts d id n o t h av e a m u c h higher

rate of chronic a n d self-lim iting som atic co m orbidity, a n d th ey h a d o nly slig h tly m o re episodes

of self-lim iting airw ay p roblem s th a n controls.

Consultations, referrals, diagnostic tests and hospital adm issions

The n u m b e r of consultations in p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s is

significantly h ig h er (n = 9.8 v ersu s n = 4.2, P<0.001), as th e n u m b e r of subjects referred for

diagnostic te stin g (n = 156 v ersu s n = 140, OR = 1.8). The n u m b e r of hom e visits w as eq u al in b o th

groups. A b o u t th ree -q u a rters of p atien ts h a d b een referred to som atic specialists, com p ared

w ith ab o u t half of th e controls. A bo u t o n e-th ird of th e p atien ts h a d b een referred to m ental

h ea lth sources co m p ared w ith less th a n 10% in controls. H o sp ital ad m issio n s w ere th e sam e.

T hese d a ta are o u tlin ed in T able 2.

Medication use

The resu lts reg a rd in g m ed icatio n use are d etailed in Table 3. W e fo u n d th a t p atien ts w ith

chronic functional som atic sym ptom s u se d a significant m o re som atic m ed icatio n (2.6 v ersu s

1.5, P<0.001) a n d p sychotropic d ru g s (0.4 v ersu s 0.05, P<0.001) p er y ear co m p ared w ith controls.

The n u m b e r of p atien ts u sin g a n tid ep ressan ts a n d b en zo d iazep in es is statistically d ifferen t in

b o th g ro u p s (35.6% v ersu s 5.9%; 52.5% v ersu s 12.7% respectively, P<0.001).

In p atien ts u sin g m edication, an tid ep ressan ts w ere u sed for a m ean of 20 days a year an d

b en z o d ia ze p in es for 9 d ays a y ear co m p ared w ith 5 a n d 4 days, respectively, in controls.

H ow ever, these fin d in g s do n o t reach statistical significance. M oreover, th ere is no difference in

p rescrib ed daily dose for p atien ts a n d controls.

34 I Chapter 2

Table 2. Number of consultations, comorbidity, referrals, diagnostic tests, and hospital admissions in patients

and controls (n = 182)

<0.001b

0.53

00

C o m o rb id ity (n [%])

Som atic chronic:

D iabetes M ellitus

A sth m a/C O P D

C ard io v ascu lar

P-value

\o

CM

LO

fN

00

Os

G P consultations in one y e ara

(mean [range])

Practice visits

H om e visits

0.2 (0-3.5)

Controls

LO

o

<N

Patients

0.3 (0-7.1)

Odds ratio (95% CI)

-

5 (2.7)

20 (11.0)

16 (8.8)

4 (2.2)

10 (5.5)

8 (4.4)

-

1.3 (0.3 to 5.7)

2.1 (0.9 to 5.0)

2.1 (0.8 to 5.5)

Som atic self-lim iting:

Skin

M usculoskeletal

A irw ay

96 (52.7)

130(71.4)

136 (74.7)

82 (45.1)

115(63.2)

113 (62.1)

-

1.4 (0.9 to 2.1)

1.5 (0.9 to 2.3)

1.8 (1.1 to 2.9)b

Psychiatric0

41 (22.5)

20 (11.0)

-

2.4 (1.3 to 4.4)b

R eferrals (n [%])

Somatic: M edical

Somatic: P a ra m e d ic a l

M ental H ealth

130 (71.4)

129 (70.9)

59 (32.4)

97 (53.3)

87 (47.8)

15 (8.2)

-

2.2 (1.4 to 3.5)b

2.6 (1.7 to 4.2)b

5.3 (2.8 to 10.3)b

D iagnostic teste (n[%])

156 (85.7)

140 (76.9)

-

1.8 (1.0 to 3.2)b

H osp ital ad m issio n s (n [%])

Som atic

Psychiatric

57 (31.3)

1 (0.5)

51 (28.0)

1 (0.5)

-

1.2 (0.7 to 1.9)

-

1.0

an = 118: one general practice did not use the computerised registration, so consultation could not be established in this practice.bStatistically significant

difference between patients and controls P<0.05. Including schizophrenia, depression, psychoses, hysteria, phobia, neuroses, post-traumatic stress

disorder, alcoholism, use of street drugs. Including physiotherapist, dietician. Including hematological tests, x-ray examinations, ultrasonography,

electrocardiography.

Discussion

Strengths and limitations of this study

The stre n g th of th e p rese n t stu d y is th a t th e p atien ts w h o w ere in c lu d ed w ere those w ho

consu lted th eir GP, irrespective of th e p rese n ted sy m p to m s. T herefore, a th resh o ld of relevance

of the sy m p to m s for th e p a tie n t w as estab lish ed an d w e w ere able to analyse all sym p to m s

presen ted . M ost p o p u la tio n -b ase d stu d ies assess all sy m p to m s irresp ectiv e of th e p erceived

n ee d for help.10;16;17 M oreover, in p o p u la tio n -b ase d stu d ies, in te rv iew in g p atien ts rep eated ly

does n o t lead to a consistent classification of so m ato fo rm d iso rd ers,18w h ereas o u r classification

of th e p rese n ted m o rb id ity is b ased on v ery stable d ata,29;34 in w h ich lo n g itu d in al research is

allow ed an d recall bias w ill n o t occur.

Chronic functional somatic symptoms: a single syndrome? | 35

Table 3. Medication use in patients and controlsa (n = 118)

Odds ratio

(95% CI)

Patients

Controls

P-value

N u m b e r of som atic m ed icatio n p e r y e ar (mean [range])

N u m b e r of psych o tro p ic d ru g s p e r y ear (mean [range])

2.6 (0-18.0)

0.4 (0-9.0)

1.5 (0-7.5)

0.05 (0-0.62)

<0.001b

<0.001b

-

N u m b e r of p atien ts u sin g psych o tro p ic d ru g s (n [%])

A ntid ep ressan ts

B enzodiazepines

O thers

42 (35.6)

62 (52.5)

3 (2.5)

7 (5.9)

15 (12.7)

3 (2.5)

-

7.5 (3.1to18.9)b

5.8 (3.0to11.1)b

1.0

19.5 (1.9-297.0)c 5.0 (1.62-91.7)d

8.9 (0.4-322.5)c 4.2 (1.1-90.8)d

3.8 (0.2-25.1)d

34.3 (1.7-58.2)

-

-

0.76 (0.20-1.37)c 0.77 (0.13-2.00)d

0.62 (0.06-1.50)c 0.61 (0.20-1.54)d

0.51 (0.25- 0.75) 0.31 (0.25-0.40)d

-

-

D ays of p sy chotropic d ru g use p e r y e ar (median

[range])

A ntid ep ressan ts

B enzodiazepines

O thers

P rescribed d a ily d ose (mean [range])

A ntid ep ressan ts

B enzodiazepines

O thers

an = 118: one general practice di not use the computerised registration, so medication could not be established in this practice. bStatistically ignificant

difference between patients and controls P<0.05. cFor patients with antidepressants, benzodiazep nes and other psychotropic drugs, n = 42 62, and 3,

respectively. dFor controls with ntidepressants, benzodiazepines and other psychotropic drugs, n ==7, 15 and 3, respectively.

The lim itations of the stu d y are the retro sp ectiv e u se of d ata in existing m edical reco rd s a n d the

possible in terd o cto r v aria tio n of th e diag n o sis of chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s.35 The

in terd o cto r v aria tio n is p artly a consequence of n o t h av in g explicitly sta te d criteria for chronic

fun ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s in the CMR. This subjectivity w ill p ossibly alw ay s exist because

d iag n o sin g chronic fun ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s rem ain s an in te rp re tatio n of th e sym ptom s,

an d is influenced by forek n o w led g e a n d context.27H o w ev er, it is k n o w n fro m th e literatu re th a t

th e G P's ju d g e m e n t o n so m atisatio n seem s v alid in daily practice. M oreover, ad d itio n al

v alid atio n of clinical ju d g e m e n t is possible th ro u g h lo n g itu d in al fo llo w -u p .36The subjectivity of

th e diagnosis a n d th e d o cto r-p atien t relatio n sh ip also m ake im p o rta n t co n trib u tio n s to the

genesis an d persistence of fun ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s.37 The d octor's k n o w led g e of the

p atien t's com plaints is an im p o rta n t issue a n d is asso ciated w ith a b etter outcom e.

O f all variables described, only consult freq u en cy is d irectly lin k ed w ith th e diag n o sis of chronic

fun ctio n al som atic sym p to m s - as such, th e h ig h er freq u en cy of G P visits w as to be ex pected a

p rio ri.38

36 I Chapter 2

Summary of main findings

This is th e first observational s tu d y u sin g lo n g itu d in al d a ta d escrib in g p atien ts in w h o m

consu ltin g th e G P for functional som atic sy m p to m s h as becom e a reg u la r w ay of presen tin g .

D u rin g th e 10 y ears before th e d iagno sis of chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s is estab lish ed

by the G P, p atien ts consult th eir G P tw ice as m uch, u se m u c h m o re som atic an d psychotropic

m edication, have m ore psychiatric m o rb id ity an d are m o re often referred to m en tal h ealth

w o rk e rs th a n controls. D u rin g these 10 years, th e n u m b e r of d iagnostic tests is slightly h ig h er in

p atien ts an d th e n u m b e r of h o sp ital ad m issio n s is eq u al in co m p ariso n w ith controls. P atients

w ith chronic functional som atic sy m p to m s are m o re likely to p rese n t sy m p to m s in tw o or m ore

b o d y system s an d they p rese n t a hig h er n u m b e r an d g reater d iv ersity of sy m p to m s to th e GP

th a n control p atients. G Ps in th is s tu d y ap p e ar to classify p atien ts as h av in g chronic fu n ctio n al

som atic sym p to m s after th ree episo d es of p rese n tin g w ith fu n ctio n al som atic sym ptom s.

Comparison with the existing literature

The fin d in g th a t p atien ts could be reco g n ized as h av in g chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s

after they h a d experienced th ree episo d es of fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s p rese n ted in tw o or

m ore b o d y system s, is an im p o rta n t one. F un ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s are often recognized

after h av in g excluded o th e r possible diagnosis. This m ay be associated w ith u n n ecessary and

p ossibly h arm fu l diagnostic strategies a n d m ay p ro m o te som atic fixation. E arly id en tificatio n of

these p atien ts co u ld p re v e n t som atic fixation, a n d enables th e G P to m odify h is /h e r

p ro ceed in g s.39 A d d itionally, this fin d in g w as co n firm ed u sin g factor analysis an d sh o w s th a t

fun ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s prob ab ly do n o t clu ster in w ell defined specific som atic

syndrom es. It also suggests th a t sy m p to m v aria tio n is g reat in th ese patients.

The concept of p atien ts w ith functional som atic sy n d ro m es p rese n tin g sy m p to m s in m an y body

system s h as also b ee n su p p o rte d b y recen t stu d ies.20T herefore, th e existence op specific som atic

sy n d ro m es sh o u ld be challenged. W ith a b ro ad -b ase d ap p ro ach , th e G P m ig h t be the

a p p ro p ria te p ractitio n er to diagnose a n d trea t these p atien ts by e m p h asizin g th e bio m ed ical as

w ell as th e psychosocial factors in v o lv ed in sy m p to m p ro d u c tio n a n d p erc ep tio n .40

The fin d in g th a t p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s d id n o t h av e a h ig h er rate of

chronic a n d self-lim iting som atic com o rb id ity is rem ark ab le because it is sta te d in th e literatu re

th a t so m atisatio n w ith m ore fre q u en t ex am in atio n m ay increase th e chance for chronic diseases

to be d iscovered.36W e fo u n d th a t m o re fre q u en t co n su ltatio n d id n o t lead to m o re d iag n o sed

chronic a n d self-lim iting diseases in p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sym ptom s.

The diagnosis chronic functional som atic sy m p to m s is n o t rec o rd e d as su ch in th e DSM-IV

classification. It no d o u b t exists as p a rt of th e sp e ctru m so m ew h ere b etw e en so m atisatio n

Chronic functional somatic symptoms: a single syndrome? | 37

diso rd er a n d som atoform d iso rd er n o t o th erw ise specified. The co n d itio n resem bles the

concept of 'ab rid g ed som atizatio n ',10 b u t is n o t b ased o n th e n u m b e r of sy m p to m s. Both

'ab rid g ed so m atization' an d chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s p resu m e u n d erly in g

psychological distress. The prevalence of so m atisatio n d iso rd er acco rd in g to th e DSM-IV in

p rim a ry care is low because of th e strin g e n t c rite ria “141 O n th e o th er h an d , less severe fo rm s of

som atizatio n have a m ajor im pact o n q u ality of life a n d o n th e use of h ea lth services, a n d are

m ore prevalent.

Implications for further research and clinical practice

P atients w ith chronic functional som atic sy m p to m s m ay b e co n sid ered as p ersisten t

com plainers a n d consequently labelled as 'difficult' patien ts. The co n d itio n m ay in d e ed reflects

a greater p ro p en sity to com plain; h ow ever, as is a p p a re n t fro m th e excess of psychiatric

com orbidity, p atien ts w ith chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sy m p to m s also have m ore reaso n to

com plain. W ith re g a rd to these patien ts, it seem s th a t c o n su ltin g th e G P for fu n ctio n al som atic

sy m p to m s h as becom e a reg u la r w ay of p resen tin g , b u t it m ig h t also be th a t p atien ts w h o a tten d

m ore often are at h ig h er risk of b ein g co n sid ered as chronic fu n ctio n al som atic sym ptom s.

M oreover, the diagnosis m ig h t relate to fru stra te d d o cto rs as a consequence of lack of

u n d e rsta n d in g , or failures in th e com m u n icatio n b etw e en d octor an d patient.

C hronic fun ctio n al som atic sym p to m s are a m ajor cause of m o rb id ity a n d d eserve fu rth er

in v estig atio n to estim ate the im portan ce of the d o cto r-p atien t relatio n sh ip , the feasibility of

treatm en ts, a n d th e u n d e rsta n d in g of th e aetiology of fu n ctio n al sy m p to m s to id en tify p atien ts

w h o are likely to becom e p ersisten t co m p lain ers a n d d ev elo p th e b eh a v io u ral p a tte rn of p atien ts

w ith chronic fun ctio n al som atic sym ptom s.

Also, th e o verlap of chronic functional som atic sy m p to m s w ith th e v ario u s DSM-IV diagnoses