Secularisms: José Casanova

advertisement

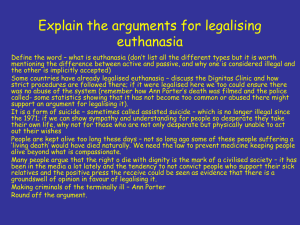

Secularisms: José Casanova “The fundamental question is how the boundaries are drawn and by whom.” Recap • ‘The secular’ has been conceived in three ways across its historical development • This development is contingent on the historical processes of western Europe • A secular world is a particular way of experiencing and conceiving of the universe and the self – Disenchantment – The ‘buffered’ vs. the ‘porous’ self 2 The Emergence of the Secular (Taylor) • Early religion sanctified the social order, such that it could be impossible to conceive of oneself outside the social matrix, accepted the order of things. – Embedded in both society and the cosmos • Durkheim & Eliade • It was celebrated by and for the community, and asked for wellbeing and worldly flourishing • Weber – “Pagan” emphasis on human flourishing has much in common with modern exclusive humanism • Postaxial religions (esp. Buddhism and Christianity) reject the world in the name of a higher truth – The order of things is called into question and delegitimized – Strong emphasis on individual thought and practice relative to preaxial religion – But the forms of preaxial religion (communal rituals, identities, etc.) remained, in tension with the implicit individualism of postaxial faiths (44-47) 3 The Emergence of the Secular (Taylor) • In the long reforming process that took place in Latin Christendom, individual practice was emphasized at the expense of ritual, which was disregarded as “magical” – “The ‘world’ itself would come to be seen as constituted by individuals.” – Efficacy of ritual comes to be inner: it doesn’t transform the world, it leaves the participant with a changed inner state • “Social life was to be purged of its connection to an enchanted cosmos and all vestiges removed of the old complementaries between spiritual and temporal, between a life devoted to God and life in the ‘world,’ between order and the chaos on which it draws.” – Social institutions come to be seen not as divinely ordained, but as human constructs enacted by free actors (47-49) – Secular good order comes to be viewed as the function of religion, meaning that it becomes possible to imagine a purely nonreligious world 4 The Emergence of the Secular (Taylor) • Multiple interacting vectors: personal commitment and disenchantment, reform and disembedding (individualism) • “The crucial change here could be described as the possibility of living within a purely immanent order; that is, the possibility of really conceiving of, or imagining, ourselves within such an order, one that could be accounted for on its own terms, which thus leaves belief in the transcendent as a kind of ‘optional extra’—something it had never been before in any human society.” – For this to happen, “there had to develop a social order, sustained by a social imaginary that had a purely immanent character, which we see arising, for instance, in the modern forms of the public sphere, market economy, and citizen state.” (50-51) 5 The Secular, Secularization, Secularism (Casanova) • The secular – “A central modern epistemic category” – Differentiated from “the religious” and so mutually constituted with it • Secularization – “actual or alleged empirical-historical patterns of transformation and differentiation” of the religious and secular spheres • Secularism – A range of views and ideologies, may become political projects (54-55) 6 Secularities • “One may distinguish three different ways of being secular: – A) that of mere secularity, that is, the phenomenological experience of living in a secular world and in a secular age, where being religious may be a normal, viable option – B) That of self-sufficient and exclusive secularity, that is, the phenomenological experience of living without religion is a normal, taken fore granted condition, and – C) That of secularist secularity, that is, the phenomenological experience of not only being passively free but also of actually having been liberated from ‘religion’ as a condition for human autonomy and human flourishing.” (60) 7 The Secular • A residual category, what’s left when religion is subtracted – But theories that posit this as a universal destiny attempt to universalize the particular Western European experience • Two kinds of Christian secularization: – The first “aims to spiritualize the temporal and to bring the religious life of perfection out of the monasteries into the secular world, so that eveyone may become ‘a secular religious monk.’” and transcending the secular/religious dichotomy by blurring the boundaries • Typical of Reformation, especially the Puritans – The second, almost opposite approach rigidly maintains the dichotomy, but aims to push the religious “into the margins, aiming to contain, privatize, and marginalize everything religious, while excluding it from any visible presence in the secular public sphere”, aiming to emancipate all secular spheres from clerical-ecclesiastical control.” • Typical of the French-Latin-Catholic cultural area, laicization and laïcité, the basic subtraction narrative (56-57) 8 But “secular” may more narrowly mean “devoid of religion” • Will modernity lead to universal irreligion as a default condition? – There are the US & South Korea, “which are fully secular in the sense that they function within the same immanent frame” yet their populations are also at the same time conspicuously religious – Modernization in non-Western societies is often accompanied by religious revival. Thus, secularization, in the sense of “devoid of religion” is hardly an inevitable or linear historical process • So it is Western Europe that appears to be the exception. Why? – According to Casanova, as a legacy of the specific political and social changes of the Enlightenment, Europeans developed a “stadial consciousness”, “which understands [the] anthropocentric change in the conditions of belief as a process of maturation and growth, as a ‘coming of age’ and as progressive emancipation.” • The experience the disappearance of religion as a natural consequence of modernization • In places where this ratcheting, “stadial consciousness” is less present, “processes of modernization are unlikely to be accompanied by processes of religious decline.” (58-60) 9 Secularizations • Secularization is talked about like it’s one thing, but it can be disaggregated into 3 related components: – A) Differentiation of ‘secular’ spheres (politics, economy, science, etc.) from religious norms & institutions – B) Theory that religious beliefs & practices decline as modernization progresses – C) Theory of privatization of religion as a precondition of modern secular & democratic politics • In Europe, these 3 things went together, so they have been presumed to be a single, teleological process – But the US is a paradigmatic case of A, while B & C have not occurred. Indeed, modernization there has often been accompanied by religious revivals • Though the separation between church & state is much stricter in the US than it is in most European societies, this does not imply the rigid separation of religion and politics • Understanding that Europe is not a universal paradigm of secularization & modernization lets us understand that there can exist multiple modernities, even within the West, and certainly in the non-West (60-61) 10 Secularizations • To make broad statements about the relationship of ‘religion’ to modernity is problematic because it’s difficult to say even what a religion is – Ironically, at the moment that scholars of religious studies begin to critique the category, “it has become an indisputable global social fact.” • “While the religious/secular system of classification of reality may have become globalized, what remains hotly disputed and debated almost everywhere in the world today is how, where, and by whom the proper boundaries between the religious and the secular ought to be drawn.” – Exactly as Europe’s secularization during modernization was historically contingent, so will non-Western modernities “also be particular and contingent refashionings and transformations of existing civilizational patterns and social imaginaries mixed with modern secular ones.” (62-64) 11 Secularizations • The fundamental question for any theory of secularization is how to account for the differences between the US and Western Europe – There is a need to “’provincialize Europe”. It is not the US that is the exception in the modernization story – Even in the West, “the modern ‘secular’ is by no means synonymous with the ‘profane,’ nor is the ‘religious’ synonymous with the modern ‘sacred.’” • The sacred remains identical with ‘the religious’ only in Durkheimian terms (ex: human rights) • “What we are repeatedly observing in the ‘glocal’ media of the global public sphere can be best understood not so much as clashes between ‘the religious’ and ‘the secular’ but, rather, as violent confrontations over ‘the sacred,’ over blasphemous and sacrilegious acts and speeches, and over the profanation of religious and secular taboos.” (64-66) 12 Secularisms • Secularism as statecraft doctrine – “Some principle of separation between religious and political authority [... This] neither presupposes or needs to entail any ‘theory,’ positive or negative, of ‘religion.’” • If it does have such a theory, it moves into the arena of ideology • Secularism as ideology – Type 1: Philosophical-historical: “secularist theories of religion grounded in some progressive stadial philosophies of history that relegate religion to a superseded age.” • Marx – Type 2: Political: “theories that propose that religion is either an irrational force or a nonrational form of discourse that should be banished from the democratic public sphere” (66-67) • Early Rawls, early Habermas 13 Ideological Secularism • Western Europeans – tend to embrace a stadial view of history, in which to be modern is “to leave religion behind, to emancipate oneself from religion, overcoming the nonrational forms of being, thinking, and feeling associated with religion. – “It also means growing up, becoming mature, becoming autonomous, thinking and acting on one’s own. It is precisely this assumption that secular people think and act on their own and are rational autonomous free agents, while religious people somehow are unfree, heteronomous, nonrational agents that constitutes the foundational premise of secularist ideology.” (68) • Americans, less influenced by the stadial view of history, see little conflict between religion and modernity (68) 14 Political Secularism • Does not tend to make the same set of assumptions about religion as ideological secularism, and may even value it as a positive force – “But political secularism would like to contain religion within its own differentiated ‘religious’ sphere and would like to maintain a secular public democratic sphere.” – “But the fundamental question is how the boundaries are drawn and by whom.” (69) 15 Political Secularism • “Political secularism falls easily into secularist ideology when the political arrogates for itself absolute, sovereign, quasi-sacred, quasi-transcendent character or when the secular arrogates for itself the mantle of rationality and universality, while claiming that ‘religion’ is essentially nonrational, particularistic, and intolerant (or illiberal)” and thus a threat to democratic politics. – In western Europe in 1998 (pre-9/11), more than 2/3 of every country agreed that religion is “intolerant” and “creates conflict” • Ahistorical: none of the ideologies that wracked western Europe in the 20th century were religious • This idea “has the function of positively differentiating modern secular European from ‘the religious other’” (premodern, religious Europeans, modern non-Europeans, esp. Muslims) (69-70) 16 Religion & Democracy • The First Amendment has two clauses: “no establishment” and “free exercise” of religion – Both of these are necessary for a coexistence of religion and democracy. Where there is no established (i.e. state, compulsory) church, politics and religion can have a friendly, rather than hostile separation of religion from democratic governance • “Disestablishment becomes a necessary condition for democracy whenever an established religion claims monopoly over a state territory, impedes the free exercise of religion, and undermines equal rights or access to all citizens.” (71-72) 17 Religion & Democracy • “Ultimately, the question is whether secularism is an end in itself, an ultimate value, or a means to some other end, be it democracy and equal citizenship or religious (i.e., normative) pluralism.” – If it is not an end in itself, “then it ought to be constructed in such a way that it maximizes the equal participation of all citizens in democratic politics and the free exercise of religion in society.” (72) 18