AAA5)The first Great Debate

advertisement

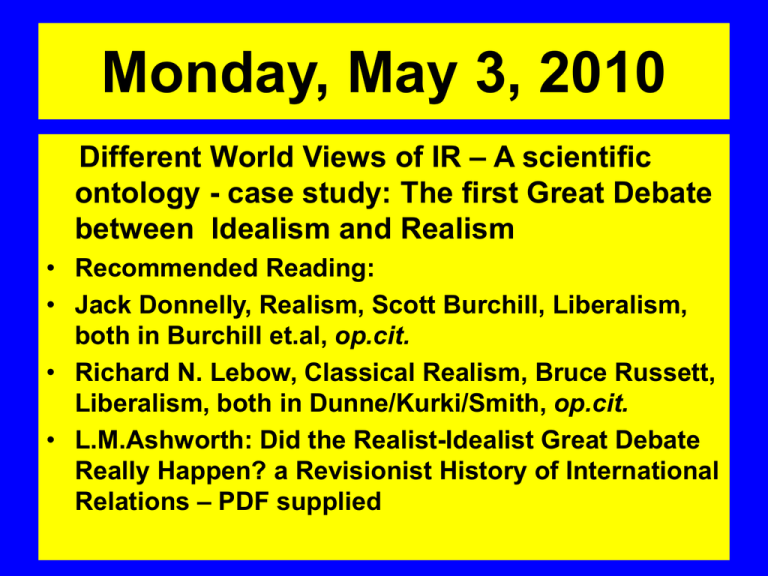

Monday, May 3, 2010 Different World Views of IR – A scientific ontology - case study: The first Great Debate between Idealism and Realism • Recommended Reading: • Jack Donnelly, Realism, Scott Burchill, Liberalism, both in Burchill et.al, op.cit. • Richard N. Lebow, Classical Realism, Bruce Russett, Liberalism, both in Dunne/Kurki/Smith, op.cit. • L.M.Ashworth: Did the Realist-Idealist Great Debate Really Happen? a Revisionist History of International Relations – PDF supplied Grand Theories of International Relations In its effort to find answers to extra-scientific political and societal crises and problems, the science of International Relations, over time, has produced a number of different Grand Theories of international politics, which try to grasp its subject matter and phenomena on the basis of different perspectives of perception/interpretation different sets of questions different anthropological different normative and ethical and different methodological predispositions and presuppositions Grand Theories of I.R. II • Grand Theories differ in view of their ontological assumptions, i.e. those assumptions referring to the nature of their research objects. • Grand Theories formulate different premisses and assumptions regarding the international milieu, i.e. the characteristic outlook, quality, and structure of the environment in which international actors act the quality, character, and substance of international actors themselves actors‘ aims and interests and the means which actors, as a rule, use in the fulfillment of their aims and interests. Grand Theories and World Views • Each and every Grand Theory formulates a characteristic world view of International Relations: Grand Theories and their world views compete with each other without offering science a possibility to decide which of the Grand Theories is the (only) correct representation of international reality. • If it would want to decide this question, science would need an Archemedian point over and beyond the competition of the Grand Theories, which would enable it to establish firm criterias for deciding on the truth or falseness of those premisses on which Grand Theories base their ontological edifice. • This Archemedian point is nowhere in sight !! Grand Theories of International Relations Grand Theory Actor Realism Milieu Structural Principle World of states as an-archic state of nature Vertical segmentation, unlimited zerosum game for power, influence, ressources World of states as legally constituted society Vertical Segmentation, zero-sum game regulated by norm and agreement World society as society of individuals and their associations Universalistic constitution Nation State English School or Rationalism Idealism Individual Grand Theories of International Relations II Grand Theory Actor Milieu Structural Principle Interdependencyoriented Globalism Individual or societal actors Transnational society Functional border-crossing networks Theories of Imperialism Individual or societal actors representing class interests International class society Border-crossing horizontal layering Dependency oriented Globalism: Dependency Theories and Theories of the Capitalist world system Societal and national actors representing class interests World system of Capitalism as layering of metropoles and peripheries Horizontal layering of national actors in the world system; structural dependence of peripheries on metropoles; structural heterogenity of peripheries States as international gatekeepers IGO = government State C = society Society C State A State B Society B Society A INGO = foreign or international societal interactions = foreign or international political interactions The modern territorial State – Substrate of the Billard-Ball-Model of International Politics Premiss: Legitimation of the state by successful completion of its functions: guarantee of law and order domestically and protection against (military)attacks in its external relations Factors of Change: Medieval starting point Development of the forces of production and destruction Wall-protected impenetrability cancels Gun powder revolution of the late middle ages: development of artillery and distance weapons Territorial State: hard shell of fortresses round periphery & parallell abolition of independence of interior fortified places by the central power Fortress protected impenetrability manifestations Strategy military power Politics: Independence Premiss: warfare rests in the horizontal Law Sovereignty Modern State: domestically pacified and externally hard shelled defensible Unit with monopoly of the use of physical force on its territory Impenetrability based on military, political, legal developments cancels Air warfare: ballistic carriers and nuclear weapons of mass destruction Political Realism • Realism, also known as political realism (in order to distinguish it from philosophical Realism), encompasses a variety of theories and approaches, all of which share a belief that states are primarily motivated by the desire for military and economic power or security, rather than ideals or ethics. This term is often synonymous with power politics. What is Realism • The term "Realism" is used with such frequency that it appears to defy the need for definition - all that needs to be known about the concept seems to be encapsulated in the word. Yet closer examination uncovers a great deal of variation. Each of the principal Realist theorists - Carr, Morgenthau and Waltz - offer their own definitions, and often focus on the aspects they wish to emphasise. • Divisions of opinion exist between the classical (or traditional) Realists and the structural Realists (neorealists); and within these broad groupings there are further variations and shades of opinion. All share a large part of a common body of thought, but many have particular aspects on which they differ. Too precise a definition excludes some individuals; too broad a description loses some common threads of thought. What is Realism II • Of the threads that make up the Realist school, the most important ideas include: • International relations are subject to objective study. Events can be described in terms of laws, in much the same way that a phenomenon in the sciences might be described. These laws remain true at all places and times. • The state is the most important actor of internaqtional politics. At different times in history the state may be represented by the tribe, city-state, empire, kingdom or nation-state. Implicit in this is that supra-national structures, sub-national ones and individuals are of lesser analytical importance. Thus the United Nations, Shell, the Papacy, political parties, interest groups, etc, are all relatively unimportant to the Realist. • The first corollary is that the international system shows a structure of anarchy, with no common sovereign. • A second corollary is that the state is a unitary actor. The state acts in a consistent way, without any sign of split purposes. • Further, state behaviour is rational - or can best be approximated by rational decision-making. States act as though they logically assess the costs and benefits of each course open to them and then optimize/maximize their gains. . What is Realism II contd. • States act to maximise either their security or power. The distinction here often proves moot as the optimum method to guarantee one‘s security is frequently equated with maximising one‘s power. • States often rely on the threat of or application of force to achieve their ends. • The most important factor in determining what happens in international relations is the distribution of power between international actors. • Ethical considerations are usually discounted. Universal moral values are difficult to define, and unachievable without both survival and power. Recommended reading Classical Authors of International Relations • • • • • • • Hedley Bull: The Anarchical Society. A Study of Order in World Politics. 3. Aufl.Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2002 Edward Hallett Carr: The Twenty Years’ Crisis 1919 – 1939. An Introduction to the Study of International Relations. 2.Aufl. London: Macmillan 1974 Hans J. Morgenthau: Politics Among Nations. New York:Alfred A.Knopf 1960 Edward L.Morse: Modernization and the Transformation of International Relations. New York: Free Press 1976 Kenneth N. Waltz: Man, the state and war. A theoretical analysis. New York: Columbia UP 1959 Adam Watson: The Evolution of International Society. A comparative historical analysis. London: Routledge 1992 Martin Wight: International Theory. The three traditions, ed. Gabriele Wight & Brian Porter. Leicester: Leicester U.P. 1991 Realism: More Characteristics • The international system is anarchic. There is no authority above states capable of regulating their interactions; states must arrive at relations with other states on their own, rather than it being dictated to them by some higher controlling entity. • Sovereign states are the principal actors in the international system. International institutions, nongovernmental organizations, multinational corporations, individuals and other sub-state or trans-state actors are viewed as having little independent influence. • States are rational unitary actors each moving towards their own national interest. There is a general distrust of long-term cooperation or alliance. Realism: Still more Characteristics • The overriding 'national interest' of each state is its national security and survival. • In pursuit of national security, states strive to amass resources. • Relations between states are determined by their comparative level of power derived primarily from their military and economic capabilities. • There are no universal principles which all states can use to guide their actions. Instead, a state must be ever aware of the actions of the states around it and must use a pragmatic approach to resolve the problems that arise. Realism – yet more… • To sum up, realists believe that mankind is not inherently benevolent but rather self-centered and competitive. This Hobbesian perspective, which views human nature as selfish and conflictual, leads to a state of nature which can only be overcome by a social contract on the societal level. Thus establishing a Leviathan on the state level, the state of nature is freed to move up the ladder of analysis to the level of the international system. • Further, they believe that states are inherently aggressive (offensive realism) and/or obsessed with security (defensive realism); and that territorial expansion is only constrained by opposing power(s). This aggressive build-up, however, leads to a security dilemma where increasing one's own security can bring along greater instability as the opponent(s) build up their own arms. Thus, international and/or security politics is a zerosum game where an increase in one party‘s security means a loss for the security of others. The Security Dilemma-Theorem Anarchic international Self-help-system Insecurity of individual actor Security regarded as military superiority Protection by military (re-)armament A arms A feels threatened A arms marginally more than B B feels threatened B arms marginally more than A B feels threatened etc. etc. What is a security dilemma ? Definition by Herz 1961 Das Sicherheits- oder Machtdilemma ist „…diejenige Sozialkonstellation, die sich ergibt, wenn (a) Machteinheiten (wie z.B. Staaten und Nationen in ihren außenpolitischen Beziehungen) nebeneinander bestehen, (b) ohne Normen unterworfen zu sein, (c) die von einer höheren Stelle gesetzt wären und sie hindern würden, sich gegenseitig anzugreifen. In einem derartigen Zustand treibt ein aus gegenseitiger Furcht und gegenseitigem Misstrauen geborenes Unsicherheitsgefühl die Einheiten in einem Wettstreit um Macht dazu, ihrer Sicherheit halber immer mehr Macht anzuhäufen, ein Streben, das unerfüllbar bleibt, weil sich vollkommene Sicherheit nie erreichen läßt.“ (Herz 1961: 130f.) Recommended Reading John H.Herz: Weltpolitik im Atomzeitalter. Stuttgart 1961. John H.Herz: Staatenwelt und Weltpolitik. Aufsätze zur internationalen Politik im Nuklearzeitalter. Hamburg 1974. The Birth of Realism: Morgenthau • In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, Hans J. Morgenthau was credited with having systematised classical Realism. His Politics Among Nations became the standard textbook, and continued to be reprinted after his death. • Morgenthau starts with the claim that he is presenting a "theory of international politics". He sees his theory bringing "order and meaning" to the mass of facts of international politics. It both explains the observed phenomena and is logically consistent, based on fixed premisses. Like Carr, he sees this Realism as a contrast to liberal idealism. The Birth of Realism: Morgenthau II Morgenthau’s theory is based on six principles he enumerates in his first chapter. In summary, these principles are: • 1. Politics, like society in general, is governed by objective laws that have their roots in human nature which is unchanging: therefore it is possible to develop a rational theory that reflects these objective laws. • 2. The main signpost of political realism is the concept of interest defined in terms of power which infuses rational order into the subject matter of politics, and thus makes the theoretical understanding of politics possible. Political realism stresses the rational, objective and unemotional. • 3. Realism assumes that interest defined as power is an objective category which is universally valid but not with a meaning that is fixed once and for all. Power is the control of man over man. The Birth of Realism: Morgenthau III • 4. Political realism is aware of the moral signifigance of political action. it is also aware of the tension between moral command and the requirements of successful political action. • 5. Political realism refuses to identify the moral aspirations of a particular nation with the moral laws that govern the universe. It is the concept of interest defined in terms of power that saves us from moral excess and political folly. • 6. The political realist maintains the autonomy of the political sphere. He asks "How does this policy affect the power of the nation?" Political realism is based on a pluralistic conception of human nature. A man who is nothing but "political man" would be a beast, for he would be completely lacking in moral restraints. But, in order to develop an autonomous theory of political behavior, "political man" must be abstracted from other aspects of human nature. Recommended reading • E.H.Carr: The 20 Years‘ Crisis 1919 – 1939. An Introduction to the Study of International Relations. 2nd ed. London: Macmillan 1974 u.ö. • Kenneth N. Waltz: Man, the State and War. A theoretical analysis. New York: Columbia UP 1959 • John A. Vasquez: The Power of Power Politics. From Classical Realism to Neotraditionalism. Cambridge: Cambridge UP 1998 Kennlinien des klassischen Realismus Historischer Hintergrund: Radizierung von Herrschaft Genese der friedens- und sicherheitsstiftenden Funktion des Territorialstaats Trennung von Innen und Aussen Entstehung des europäischen Staatensystems seit 1648/1713 Ideengeschichtliche Quellen: Machiavelli Entwicklung des Staatsräsongedankes als legitimatorischer Bezugspunkt für die Selbstbehauptung des modernen Territorialstaats. Hobbes Überwindung des innergesellschaftlichen Naturzustands durch die gesellschaftsvertragliche Begründung des Leviathan; Legitimation von Herrschaft als Garant einer territorial abgegrenzten sicherheitsgemeinschaftlichen Schutzzone: Basis der Souveränitätsanspruchs; Freisetzung des Naturzustands-Konzepts zur Charakterisierung der Beziehung zwischen solchen Schutzzonen (d.h. souveränen Staaten) Idealtypisch-metaphorische Charakteristika der internationalen Politik Idealtypisch-metaphorische Charakteristika der internationalen Politik Systemebene anarchische Struktur Sicherheitsdilemma: Erhöhung der eigenen Sicherheit durch Stärkung militärischer Fähigkeiten verringert die Sicherheit anderer; Folge: spiralenförmiger Rüstungswettlauf Gleichgewicht der Mächte durch Abschreckung Internationale Politik als Nullsummenspiel staatlicher Akteure um Macht, Ressourcen, Einfluss Akteursebene exklusiver Handlungsanspruch der Akteure im Bereich der „high politics“ Territorialität: Schutzfunktion der harten Schale zweckrationales, nutzenmaximierendes /nutzen-optimierendes Handeln Prinzip der (notfalls militärischen) Selbsthilfe bei der Durchsetzung von Interessen Recommended reading • Robert G. Wesson: State Systems. International Pluralism, Politics, and Culture. New York: Free Press 1978 • Hedley Bull: The Anarchical Society. A Study of Order in World Politics. 3.Aufl. Basingstoke: Palgrave 2002 • Barry Buzan/Richard Little: International Systems in World History. Oxford: OUP 2000 • Heinz Duchhardt/Franz Knipping (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Geschichte der Internationalen Beziehungen in 9 Bänden. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh 1997ff The English School in IR Theory The 'English School' • Particular strand of international relations theory, also known as Liberal Realism, Rationalism, Grotianism or the British institutionalists, maintains that there is a 'society of states' at the international level, despite the condition of 'anarchy' (literally the lack of a ruler or world state). Its strongest influence is functionalism, but it also draws heavily on realist and critical theories. also known as International Society Theory • focuses on the shared norms and values of states and how they regulate international relations. Examples of such norms include diplomacy, order, and international law. Unlike neo-realism, it is not necessarily positivist. Theorists have focused particularly on humanitarian intervention, and are subdivided between solidarists, who tend to advocate it more, and pluralists, who place greater value in order and sovereignty. Reexamination of traditional approaches • A great deal of the English School of thought concerns itself with the examination of traditional international theory, casting it into three divisions (described by Buzan as the English schools' triad): • Realist or Hobbesian (after Thomas Hobbes) • Rationalist (or Grotian, after Hugo Grotius) • Revolutionist (or Kantian, after Immanuel Kant). • In broad terms, the English School itself has supported the rationalist or Grotian tradition, seeking a middle way (or via media) between the 'power politics' of realism and the 'utopianism' of revolutionism. • Later Wight changed his triad into a four part division by adding Mazzini (see: Martin Wight, Four Seminal Thinkers in International Theory: Machiavelli, Grotius, Kant, and Mazzini). International Society • International relations represents a society of states. This international society can be detected in the ideas that animate the key institutions that regulate international relations: war, the great powers, diplomacy, the balance of power, and international law, especially in the mutual recognition of sovereignty by states. • Kai Alderson/Andrew Hurrell (eds.): Hedley Bull on International Society. Basingstoke 1999 • Cf. also HIP, 11th ed, Krieg und Frieden, Fig. 4 International Society II • There are differing accounts concerning the evolution of those ideas, some (like Martin Wight) arguing their origins can be found in the remnants of medieval conceptions of societas Christiana, and others such as Hedley Bull, in the concerns of sovereign states to safeguard and promote basic goals, especially their survival. Most English School understandings of international society blend these two together, maintaining that the contemporary society of states is partly the product of a common civilization - the Christian world of medieval Europe, and before that, the Roman Empire - and partly that of a kind of Lockean contract. Recommended reading: Key Works • Hedley Bull, The Anarchical Society (1977). • Herbert Butterfield, Martin Wight (eds), Diplomatic Investigations (1966). • Martin Wight, Four seminal thinkers in international theory : Machiavelli, Grotius, Kant, and Mazzini (2005) • Martin Wight, Systems of States (1977) • Martin Wight, Power Politics (1978) • Martin Wight, International Theory. The three traditions (1991) Recommended reading • Adam Watson: The Evolution of International Society. A comparative historical analysis. London 1992 • Hedley Bull/Adam Watson (eds): The Expansion of International Society. Oxford 1984 • Tim Dunne: Inventing International Society. A History of the English School. Basingstoke 1998 • Barry Buzan: International Society and World Society, Cambridge 2004 • Andrew Linklater and Hidemi Suganami, The English school of international relations: a contemporary reassessment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 2006) Website • www.polis.leeds.ac.uk/research/internat ional-relations-security/english-school/ Liberalism – result of changing internat. boundary conditions overcomes Military and political impenetrability protected by force underlines Penetrability Globalization functional Interdependence Transnational networking Further differentiation of international division of labour Environmental problems & their secondary effects crossing borders Intensification of social and cultural forces by social change Replacement of Fordistic by Postfordistic Accumulation Air Warfare, in particular ballistic weapons of mass destruction Modern industrial dynamics LOOKING AT THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM FROM A RECENT INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS PERSPECTIVE For some time already, the analysis of International Relations is characterised by a change in perspective - away from the state as a unitary actor acting as a gatekeeper between the domestic and international policy areas - up, down, and sideways to supra-state, sub-state, and non-state actors. From the society of states, our focus of attention has consequently shifted to transnational and transgovernmental societies which take the form of boundary-crossing networks amongst individuals and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs). Cobweb model of international Relations International flight connections, 2010 Transnational Society (of Actors) Government Government Government Transnational Society A Society National Actor B Society C Society Transnational Politics Government A Society Government B Society Government C Society Liberalism/Idealism • Liberalism or Idealism covers a fairly broad perspective ranging from Wilsonian Idealism through to contemporary neo-liberal theories and the democratic peace thesis. • States are but one actor in world politics, and even states can cooperate through institutional mechanisms and bargaining that undermine the propensity to define survival interests simply in military terms. • States are interdependent and other actors such as Transnational Corporations, INGOs, IGOs, and the United Nations play a decisive international role • Source: http://home.pi.be/%7Elazone/ir_theory_overview.html Liberalism/Idealism II • The goal of liberal internationalism is to achieve global structures within the international system that are inclined towards promoting a liberal world order. To that extent, global free trade, liberal economics and liberal democratic political systems are all encouraged. In addition, liberal internationalists are dedicated towards encouraging democracy to emerge globally. Once realized, it will result in a 'peace dividend', as liberal states have relations that are characterized by nonviolence, and that relations between democracies is characterized by the democratic peace thesis. Recommended reading • Relevant chapters in David A. Baldwin (ed): Neorealism and Neoliberalism: The Contemporary Debate, and Charles W. Kegley (ed): Controversies in International Relations: Realism and the Neoliberal Challenge. • Michael W. Doyle: Liberalism and World Politis, in: American Political Science Review 80 (1986), pp. 1151 - 1169 Liberalism/Idealism III • Key intellectual progenitors: Locke, Rousseau, Kant • Variants – Idealism/ Liberal Internationalism: A political theory founded on the natural goodness of humans and the autonomy of the individual. It favours civil and political liberties, government by law with the consent of the governed, and protection from arbitrary authority. Corporations, the IMF and the United Nations play a role. (Source: http://www.irtheory.com/know.htm) – Neoliberalism – Complex Interdependence – Democratic Peace Theory (Kant) Waltz v. Kegley Waltz Kegley International politics is anarchical, and anarchy is the necessary cause of war. Therefore, war and conflict are ultimately located at the international level and cannot be eliminated because anarchy cannot be eliminated International politics can be reorganized around international society rather than international anarchy, potentially eliminating problems like war and conflict and replacing international anarchy with international hierarchy (world government) Two Most Different Accounts of International Anarchy Realism Idealism Goals Survival Survival Actors’ behavior under Anarchy Increase power to ensure survival Promote social learning though: •Institutions •Ideas What forms state behavior? Self-help because •No world gov’t •Cooperation amongst states unreliable International society as cooperation of free association of individuals Logic of anarchy Conflictual, zerosum game Cooperative, win-winsituations Good evening & good bye…