ASSC

advertisement

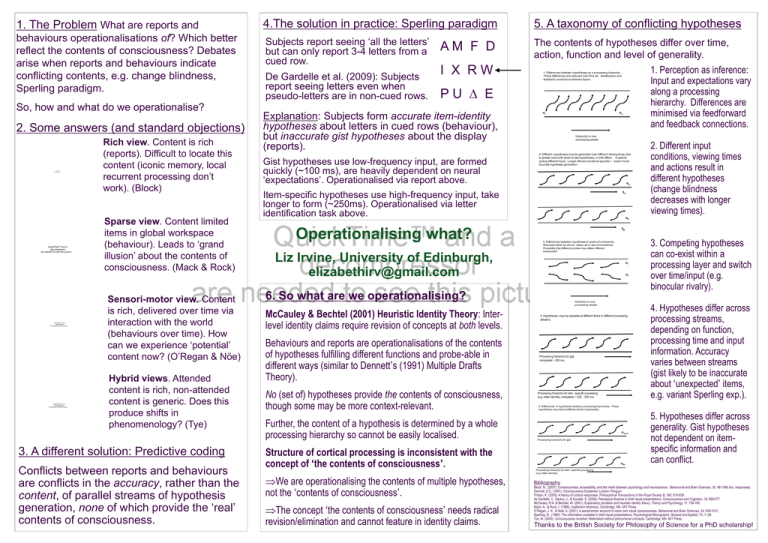

1. The Problem What are reports and 4.The solution in practice: Sperling paradigm 5. A taxonomy of conflicting hypotheses behaviours operationalisations of? Which better reflect the contents of consciousness? Debates arise when reports and behaviours indicate conflicting contents, e.g. change blindness, Sperling paradigm. Subjects report seeing ‘all the letters’ but can only report 3-4 letters from a cued row. The contents of hypotheses differ over time, action, function and level of generality. So, how and what do we operationalise? 2. Some answers (and standard objections) QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. Rich view. Content is rich (reports). Difficult to locate this content (iconic memory, local recurrent processing don’t work). (Block) Sparse view. Content limited items in global workspace (behaviour). Leads to ‘grand illusion’ about the contents of consciousness. (Mack & Rock) Sensori-motor view. Content is rich, delivered over time via interaction with the world (behaviours over time). How can we experience ‘potential’ content now? (O’Regan & Nöe) Hybrid views. Attended content is rich, non-attended content is generic. Does this produce shifts in phenomenology? (Tye) 3. A different solution: Predictive coding Conflicts between reports and behaviours are conflicts in the accuracy, rather than the content, of parallel streams of hypothesis generation, none of which provide the ‘real’ contents of consciousness. De Gardelle et al. (2009): Subjects report seeing letters even when pseudo-letters are in non-cued rows. AM F D I X RW 1. Perception as inference: Input and expectations vary along a processing hierarchy. Differences are minimised via feedforward and feedback connections. 1. Differences between hypotheses up a processing hierarchy . These differences are reduced over time via feedforward and feedback connections between layers. PU ∆ E Explanation: Subjects form accurate item-identity hypotheses about letters in cued rows (behaviour), but inaccurate gist hypotheses about the display (reports). Gist hypotheses use low-frequency input, are formed quickly (~100 ms), are heavily dependent on neural ‘expectations’. Operationalised via report above. H1 Hn Hierarchy in one processing stream 2. Different hypotheses may be generated over different viewing times (due to greater input with which to test hypotheses), or with differe nt actions (giving different input). Longer stimulus durations typically r esult in more accurate hypothesis generation. HA t1 Item-specific hypotheses use high-frequency input, take longer to form (~250ms). Operationalised via letter identification task above. Operationalising what? Liz Irvine, University of Edinburgh, elizabethirv@gmail.com HB t2 3. Differences between hypotheses in layers of a hierarchy. Resolved either by winner -takes -all or use of a threshold. Possibility that different probes may utilise different thresholds? H1 H2 6. So what are we operationalising? Hierarchy in one processing stream McCauley & Bechtel (2001) Heuristic Identity Theory: Interlevel identity claims require revision of concepts at both levels. 4. Hypotheses may be available at different times in different processing streams. Behaviours and reports are operationalisations of the contents of hypotheses fulfilling different functions and probe-able in different ways (similar to Dennett’s (1991) Multiple Drafts Theory). Processing hierarchy for gist, completed ~ 200 ms. No (set of) hypotheses provide the contents of consciousness, though some may be more context-relevant. Further, the content of a hypothesis is determined by a whole processing hierarchy so cannot be easily localised. Structure of cortical processing is inconsistent with the concept of ‘the contents of consciousness’. We are operationalising the contents of multiple hypotheses, not the ‘contents of consciousness’. The concept ‘the contents of consciousness’ needs radical revision/elimination and cannot feature in identity claims. 2. Different input conditions, viewing times and actions result in different hypotheses (change blindness decreases with longer viewing times). Processing hierarchy for item -specific processing (e.g. letter identity), completed ~ 220 -300 ms. 5. Differences in hypotheses between processing hierarchies. These hypotheses may exist at different levels of generality. HA=>B Processing hierarchy for gist HÂB 3. Competing hypotheses can co-exist within a processing layer and switch over time/input (e.g. binocular rivalry). 4. Hypotheses differ across processing streams, depending on function, processing time and input information. Accuracy varies between streams (gist likely to be inaccurate about ‘unexpected’ items, e.g. variant Sperling exp.). 5. Hypotheses differ across generality. Gist hypotheses not dependent on itemspecific information and can conflict. Processing hierarchy for item -specific processing (e.g. letter identity) Bibliography Block, N. (2007). Consciousness, accessibility, and the mesh between psychology and neuroscience. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30, 481-548 (inc. responses). Dennett, D.C. (1991). Consciousness Explained. London: Penguin. Friston, K. (2005). A theory of cortical responses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 360, 815-836. de Gardelle, V., Sackur, J., & Kouider, S. (2009). Perceptual illusions in brief visual presentations. Consciousness and Cognition, 18, 569-577. McCauley, R.N. & Bechtel, W. (2001). Explanatory pluralism and heuristic identity theory. Theory and Psychology, 11, 736-760. Mack, A., & Rock, I. (1998). Inattention blindness. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. O’Regan, J. K., & Noë, A. (2001). A sensorimotor account of vision and visual consciousness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24, 939-1031. Sperling, G., (1960). The information available in brief visual presentations. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 74, 1–29. Tye, M. (2009). Consciousness revisited: Materialism without phenomenal concepts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Thanks to the British Society for Philosophy of Science for a PhD scholarship!