CAUSATION

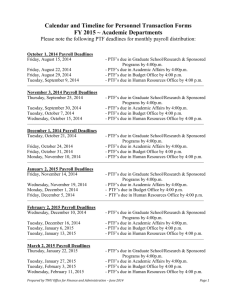

advertisement

CAUSATION In order to establish a cause of action in negligence, a major requirement is that the plaintiff must show a causal link between the defendant’s breach of duty and the injury suffered by the plaintiff. Before we deal with causation, let us first dispose of the question of “injury” or “damage” which the law of negligence would countenance. Damage Defined Negligence law does not countenance mere violation of dignitary interest like one’s personal reputation or integrity. Rather, the type of “damage” or “injury” which negligence law would offer redress is often a question of policy defined by reference to whether a “duty of care” obligated the defendant NOT TO cause the “injury” or damage in question. Damage Defined The concept of “damage” is relative, dependent on the circumstances of the occasion. Physical injuries and property damage are apparent and far less problematic. On the other hand, mental injuries and economic losses are actionable only under more restrictive conditions. There are circumstances where the injury takes a long time to manifest, in those cases, no right of action will arise until the injury manifests itself. Damage Defined The importance of this principle may be summarized thus: A) It avoids speculative claims, B) It sets the time when the statute of limitation begins to run (this is advantageous to plaintiffs). THEORIES OF CAUSATION As already noted, there is no liability in negligence unless the dft’s negligent conduct “caused” the ptf’s “injury”. The question then is whether “causation” is a matter of fact (objective) or a policy driven (subjective) criterion? Fleming and some other scholars posit that the issue is one of fact. Other scholars have argued that policy considerations may weigh heavily in determining “cause in fact”, eg, in injury arising from a “chain reaction” or by “Murphy’s law”. Fleming on Causation Fleming argues that causation is a solely a question of whether “the dft’s breach of duty and the ptf’s injury is one of CAUSE and EFFECT in accordance with objective notions of PHYSICAL SEQUENCE. If such a causal relation does not exist, that puts an end to the ptf’s case.” Fleming, at 218. Barnett v. Chelsea & K. Hospital A watchman, after drinking some “tea” which made him vomit, went to the casualty department of the defendant’s hospital. His complaints were recorded by the nurse who in turn passed them on to a casualty medical officer. The latter asked the nurse to tell the watchman to go home and consult his own doctor. Some hours later, the watchman died from arsenical poisoning. The court absolved the dft from liability on the ground that the negligence of the dft did not cause the death. Causation ad infinitum? Given that the consequences of a negligent act may theoretically stretch into infinity, there must be a limit to the legal responsibility for the consequences of the negligent act. It is within this context that the theory of “causation” as a construction of policy (subjective) becomes tenable. Value judgments and legal policy may be deployed to delimit “causation.” …For Want of a Nail… For want of a nail the shoe was lost For want of a shoe the horse was lost For want of a horse the rider was lost For want of a rider the battle was lost For want of a battle the kingdom was lost And all for the want of a horseshoe nail Query: Who lost the kingdom? The negligent blacksmith? Kaufmann v. T.T.C While ascending an escalator at the St. Clair station of TTC, ptf was injured when she fell after two scuffling youths ahead of her fell back on a man, who in turn, fell back on her. The SC reasoned that given that the provision of better handrails at the station would not have prevented the accident, there was no causal link between the ptf’s injury and the lack of better hand rails at the station. PROOF OF CAUSAL LINK The courts have not developed a single test for satisfying the causal requirement. In theory, every injury is the culmination of many conditions that are “jointly sufficient to produce it.” There are complex contributory factors at work to produce damage or injury. For example, dropping a lighted match in a wastepaper basket ignites the basket. Note that there must be (a) combustible material (paper) and (b) oxygen to produce the fire. Query: What “caused” the fire? The “But for” Test The first test is whether the alleged factor in the “causation” chain is NECESSARY to complete the set of conditions sufficient to produce the injury in question.This test is universally known as the “But For” test. If it can be proved, on the balance of probabilities, that the plaintiff’s injury would not have occurred WITHOUT (but for) the defendant’s negligent conduct, the causal connection IN FACT is established. (Klar, at 321) …But For… In other words, applying the “but for” test, there would be no liability where the injury or damage would have regardless of the defendant’s conduct. The primary function of the test is to weed out from further consideration factors which would not have made any difference to the outcome. It is thus a speculative and evaluative test. …But For… The “but for” test requires the court to use its human experience, best judgment, intuition, common sense, and sometimes, expert evidence to speculate on what might ordinarily have happened “but for” the defendant’s conduct. However, the decision is one which need not be made with mathematical certitude. The Scope of the “But For” Test The test is not necessarily CONCLUSIVE. The factor in question, beyond passing the “but for” test must scale the additional hurdle of “proximate” or “legal” cause. The “but for” test is thus a NECESSARY but insufficient condition of legal responsibility. Material Contribution Test Initially, the courts insisted on a doctrine of strict proof of causation. While this doctrine was tenable in cases where a single cause could be attributed to a harm, in other cases where multiple, independent “causes” may bring about a single harm, the “but for” test proved unworkable. In the latter type of cases, it is virtually impossible to prove causation with mathematical precision. In attempting to remedy this defect, the courts devised another test known as the “material contribution test.” The Material Contribution Test Thus, in cases where more than one set of sufficient conditions can account for a single injury, the courts ask the question whether each of the conditions was a substantial factor. For example, if two persons simultaneously approach a leaking gas pipe with lighted candles and the resulting inferno burns down a neighboring house, it would be unwise to apply the “but for” test as both tortfeasors may then escape liability. See Walker Estate v. York Finch Gen. Hospital The Material Contribution Test In effect, where there are multiple “causes” each independently capable of “causing” the single harm in question, all that the plaintiff is required to prove is that the dft’s negligence “materially contributed” to the injury. Query: if firefighters arrive late and without equipment, would the owner of a burnt down house succeed in an action in negligence against the firefighters? Materially Increased Risk Another test, now discredited is “did the dft’s negligence “materially increase the risk” of injury to the ptf? This test was formulated McGhee’s case. The ptf contracted dermatitis from the dft’s brick yard. The dft’s failure to provide washing facilities was held to be negligent but it was unclear whether the provision of washrooms would have prevented the disease. There was evidence, however, that the absence of washrooms materially increased the risk of the ptf contracting dermatitis. Retreat from McGhee The full significance of McGhee is that all activities which unreasonably increase risk of injury in society are negligence in law even when such activities have not in fact caused any injury. This was a radical, albeit unintended redefinition of negligence law. Another implication is that proof by ptf that dft’s conduct “materially increased the risk” shifts the onus of proving lack of causation to the defendant. The SC departed from the logic of McGhee in Snell v. Farrell. Snell v. Farrell Ptf became blind in one eye following a cataract operation by the dft. The trial judge found the dft negligent because he continued with the operation after noticing bleeding in the ptf’s eye. Apart from the dft’s conduct, there were other probable causes of the ptf’s blindness. Applying McGee, the trial judge shifted the onus of proving lack of causation to the dft. On a final appeal to the SC, it was held that: Snell v. Farrell Ordinary causation principles properly applied are adequate to deal with most cases in negligence. Principles of proof must not be applied too rigidly . Causation is a practical question of fact that can be answered by ordinary common rather than abstract metaphysical theory. The courts may therefore use their general knowledge of life to draw reasonable inferences of causation. Impact of Snell on “but for” test Put simply, in cases where scientific evidence cannot establish on a balance of probabilities the connection between dft’s conduct and ptf’s injury, the ratio in Snell v. Farrell requires the courts to substitute the “but for” test with reasonable inference of the cause of the injury. This is a significant fudging of the rule that a ptf can only win if s/he proves his/her case on a balance of probabilities. Multiple Causes There are cases where an injury may have been caused by more than one tortfeasor. In such cases, proof of causation cannot be done by reliance on the “but for” test. In Fairchild’s case, the House of Lords (HOL) had cause to deal with this sort of problem. Employers had sued 2 employees for respectively failing to take measures that would have prevented the employees from inhaling asbestos. The employees had contracted mesothelioma. Multiple Causes Both employers exposed the employees to the risk of inhaling asbestos dust but it was unclear and could not be scientifically which particular employer had caused the damage. Both employers had exposed the employers to the same risk of injury. The HOL was faced with the dilemma of applying the “but for” test (which would lead to a dismissal of the suit against the dfts or tweaking the “but for” test in order to grant relief to the ptfs. Fairchild v. Glenhaven If the HOL applied the “but for” test, both employers would escape liability, as neither would be the cause of the mesothelioma. Applying the “material contribution” test, the HOL found for the ptfs. Query: What are the concerns with the “material contribution” test? And what policy reasons dictate its bias against well heeled defendants? Athey v. Leonati The material contribution test cannot be used to apportion liability between tortious and non-tortious causes. See Athey v. Leonati. For it to apply, both possible causes of the injury but respectively be tortious. Cottrelle v. Gerrard Ptf’s left foot became gangrenous and had to be amputated below the knee. Trial judge found that dft doctor was negligent in treating ptf’s diabetes. However, given the preexisting medical condition (First Nations Canadian, a smoker and thus at a higher risk of developing vascular disease and diabetes which could have developed into a gangrenous tissue on the foot) ptf and dft expert witnesses were unsure as to whether ptf’s left leg would have been saved by the dft. It was held that the dft was not liable.