File - Teaching With Crump!

advertisement

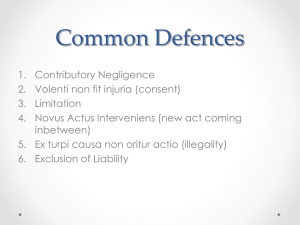

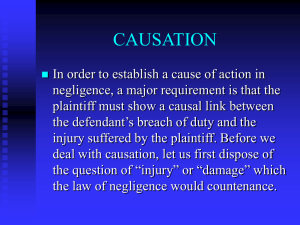

Liability in Negligence Damage caused by the Defendant’s breach Lesson Objectives • I will be able to distinguish between causation in fact and remoteness of damage • I will be able to distinguish between damage and damages • I will be able to state and explain factual causation in negligence • I will be able to state and explain the test for remoteness of damage General Principles • If there is to be liability in negligence, the broken duty must have caused the loss complained of, and the loss must not be too remote from the act • This is often referred to as damage and must be distinguished from damages which is the amount of compensation awarded • There are two parts to damage: causation and remoteness. Causation is the idea that the defendant must have caused the loss complained of – this is causation in fact (this is the same concept as in criminal law, but it illustrated by examples from the law of negligence) • If no loss is caused then there is no claim in negligence • Remoteness is concerned whether the loss is reasonably foreseeable: causation in law • Both must be proved following a broken duty of care if there is to be liability for a claim in negligence Situation: Defendant’s act or omission Drives car into claimant’s car Causation in fact: Apply ‘but for’ test Minor damage to car and whiplash injury to claimant Causation in law: Take your victim as you find him/unusual form of foreseeable injury Claimant already has a weak neck from previous accident and in fact breaks neck Causation in fact • This is the starting point – if there is no causation in fact, there is no point in considering whether there has been causation in law • Causation in fact is determined by the ‘but for’ test – this test is satisfied if it can be said that, but for the defendant’s act or omission the claimant would not have suffered loss or harm • A different way of stating the test is to ask whether the prohibited result would have occurred if the defendant had not acted – if it still would have occurred, even without the D’s actions, then factual causation is not present • Barnett v Chelsea and Kensington Hospital Management Committee (1968) – this is an example where there was no causation in fact as the hospital could not have done anything to save Barnett’s life. The cause of the death was the original poisoning, not the hospital’s failure to examine him properly Multiple causes • It is not always straightforward to establish that the defendant’s act or omission caused the loss complained of – sometimes there is more than one possible cause • The courts have started to use a modified rule on the grounds of public policy where there are ‘special circumstances’ • Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd (2002) – the normal rule on causation in fact can be modified on policy grounds where there are ‘special circumstances’. Here this was because it is impossible to prove when asbestos actually entered the system to cause illness • Barker v Corus (2006) – this case modifies the ‘but for’ test in asbestos cases only and should be seen as a special exception to ensure some remedy for the victim Intervening events • As with criminal law, an intervening act can break the chain of causation – novus actus interveniens (new act intervening) • The defendant’s act may be said to cause the claimant’s damage, in that it satisfies the ‘but for’ test, but a second factual cause is the real cause of the damage • The principle that is applied is whether the resulting damage was a foreseeable consequence of the original act. The cases often appear to be decided on the basis of producing a just result as each set of facts are very different • Smith v Littlewoods (1987) – vandals breaking into an unoccupied, but secured, building and setting fire to it was a new act intervening when vandals were not common in the area • Corr v IBC Vehicles (2006) – depression following a serious accident and subsequent suicide is seen as a result of the original accident and not as a novus actus interveniens Remoteness of damage – the test of reasonable foreseeability • Where there is factual causation, the claimant may still fail to win his case, as the damage suffered may be too remote – the breach of duty may have significant results, but the defendant will not be liable for everything that can be traced back to the original act • Clearly there are some far-fetched results that are not foreseeable and therefore are not recoverable – example from the book • The test is that the defendant is liable for damage only if it is the foreseeable consequence of the breach of duty • Overseas Tankship (UK) Ltd v Morts Dock and Engineering Co. Ltd (1961) – known by the ship’s name: The Wagon Mound – damage by the spilt oil was foreseeable; damage by the fire was not foreseeable and was therefore too remote Remoteness of damage – the kind of damage must be reasonably foreseeable • The principle here is that as long as the type of damage is foreseeable, it does not matter that the form it takes is unusual • Bradford v Robinson Rentals (1967) – as long as the type of damage is foreseeable, it does not matter that the form it takes is unsual. In this case, frostbite was an extreme form of injury from the cold • Hughes v Lord Advocate (1963) – another example of a claimant succeeding for injury caused by an extreme type of harm (an explosion and fire being an extreme type of a burn) • Doughty v Turner Asbestos (1964) – the claimant was injured when a lid was knocked into a vat of molten metal and the vat erupted. Scientific knowledge could not predict the eruption, so the event was unforeseeable. The claim failed Remoteness of damage – take your victim as you find him • This is similar to the concept in criminal law – a person’s liability in negligence is not extinguished or lessened because the claimant had a pre-existing condition that made the injuries worse • Smith v Leech Brain (1962) – the claimant had a pre-cancerous condition. He was splashed on the lip by some molten metal. The burn turned into a cancer as a result of his condition. His claim succeeded Remoteness of damage – a recent example of how a judge should apply the principle of reasonable foreseeability • Gabriel v Kirklees Metropolitan Council (2004) – this example of how a judge should apply the reasonable foreseeability test involved children playing on an unfenced building site