Process Philosophy and Buddhism - Process Philosophy for Everyone

advertisement

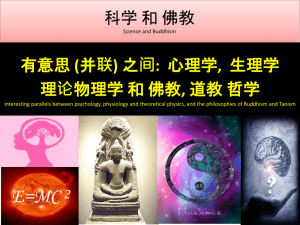

Process Philosophy and Buddhism Dr. Jay McDaniel Ecological Civilization International What is this Power Point About? For twenty five years scholars in different parts of the world have been drawing parallels between Whitehead’s “Process Philosophy” and ideas in Buddhism. I offer list of twenty-five parallels, each of which could become an article or book-length study. My hope is that some among these ideas might be helpful to scholars and practicing Buddhists in China who are interested in learning about process philosophy and perhaps using it as a framework for research and practice. Where Can I Get this Power Point? This Power Point can be downloaded online and used freely: http://www.worldwideprocess.org/proces s-philosophy-and-buddhism-powerpoint.html Experience Both emphasize experience as that starting point for wisdom Wisdom and Compassion Both believe that wisdom and compassion are complementary virtues that enrich one another. Momentariness Both emphasizes that life unfolds momentby-moment and that moments are the very building blocks of reality. Impermanence Both recognize that, as life unfolds, the subjective immediacy of each present moment passes away and cannot be regained. Karma Both believe that as our lives unfold, the decisions we have made in the past influence us, as do things that have happened in the lives of other people. We are “causally influenced” by the past. No-Self Both recognize that the human self is not a skin-encased ego cut off from the world or an enduring substance, but rather the reality of the present moment, lived from the inside. There is no “substantial” self. Inter-Being Both recognize that each moment of a person’s life is connected with every other moment in the universe. The universe is a vast network of inter-being or interdependence or inter-penetration, in which all entities are present in all other entities. Buddha-Nature (I) Both recognize that there is something like creativity or intrinsic value within each and every living being: human, plant, animal, crystal. Buddha-Nature (II) Both recognize that each and every living being aims at, or seeks, satisfaction in life. Each being has a kind of enlightenment or fulfillment which is the completion of its subjective aim. Suffering (Dukkha) Both recognized that much of life unfolds in a spirit of suffering or dukkha: an absence of ease or peace of mind. This dis-ease comes from suffering and missed potential. Many human activities – religion, art, philosophy – are attempts to deal with, to make something meaningful, of this suffering. Realms of Rebirth Both believe that we live in a multidimensional universe, of which threedimensionality is only one form. Both are open to the possibility that there may be “realms” other than the three dimensional realm and that other kinds of entities can dwell in these realms. Rebirth (I) Both believe that it is possible that the human stream of consciousness continues after death in an ongoing journey until wholeness is realized. Both believe that it is possible that, in the present moment, humans can remember past lives. Rebirth (II) Both believe that, even if there is no life before or after physical death, that this very life is an ongoing process of death and rebirth, moment by moment. An old self dies and a new one takes its place with every breath. Breathing Meditation In both perspectives “breathing meditation” makes sense as a way of calming the mind and taking nourishment from the process of breathing itself, as experienced in the mode of causal efficacy. In these moments the mental pole of our experience subsides and we become our breathing. Many Forms of Meditation Both recognize that “consciousness” is only the tip of the experiential iceberg and that there are multiple states of awareness and feeling into which we can enter, many of which may be related to the activity of seeking wholeness or enlightenment. There are many valuable forms of meditation and “samadhi” in addition to breathing meditation. Bodhisattva Vow Both recognize that there dwells within the human heart an impulse to become the best person one can be, growing in wisdom and helping others, even if the help does not bear fruit. In Whitehead’s philosophy this impulse is called the initial aim. It is an indwelling lure to become a Bodhisattva Guan Yin Mahayana Buddhists and Whitehead recognize that there dwells within the very heart of the universe a loving presence whose outstretched hands reach into the hearts of all living beings, sharing in their sufferings and guiding them toward wholeness. Whitehead calls this God; many Mayahana Buddhists call this Guan Yin. Learning from Body to Mind Both Whitehead and Buddhists recognize that learning unfolds in a person’s life, not simply from mind to body but also from body to mind. We learn by doing. This is an aspect of what Whitehead calls the wisdom of the body. Koans In Whitehead as in Buddhism, the mental pole of experience can become overly rigid, trapped in ideologies that stifle creativity and obstruct compassion. Koans function as roadblocks to the rigidified imagination, opening up new possibilities for wisdom and compassion, understanding and empathy. Enlightenment In a Whiteheadian context the experience of Enlightenment can be understood in two ways: the self-awakening of the universe within a single moment of experience or the awakening of the true self to the fact that there is no self other than the universe. In either case, enlightenment is only the beginning of a journey. It never ceases and there is always more to enlightenment than a person knows. Even the Buddha grew in enlightenment during his lifetime. It is a journey The Eightfold Path Process Philosophy and Buddhism emphasize that we learn, not only by reading and talking and discussing, but also by practicing and by more active forms of doing. Right speech, right livelihood, right association – these are forms of learning Here-and-Now Both Whitehead and Buddhism, especially Ch’an Buddhism, recognize that the hereand-now is the only “time” when subjective immediacy occurs. If we cannot find wisdom and compassion in the here-andnow, we cannot find it at all. The present moment is holy ground. Mindfulness Process philosophy and Buddhism recognize that “consciousness” is a unique form of experience that can, at its best, be relaxed and focussed, in an undistracted way, on what is happening. It is deep listening, with the eyes and heart as well as the ears. It is mindfulness, one of the most important steps in the Eightfold Path. Socially-Engaged Buddhism Thich Nhat Hahn tells us that the wisdom of compassion does not stop with being kind to others in a one-on-one way; instead it is actively engaged in helping make the world a better place through social service. It seeks to help improve pollution of the mind and also pollution in the air. It is socially engaged. Eco-Buddhism The Buddha attained enlightenment under a Bodhi tree. Tradition tells us that, when he was challenged by Mara, the Earth came to his support. These and other traditions in Buddhism invite us to recognize that a healthy Buddhism for the future will be an eco-Buddhism, in which the earth is recognized as the context for our lives, and other beings respected in tenderness and love.