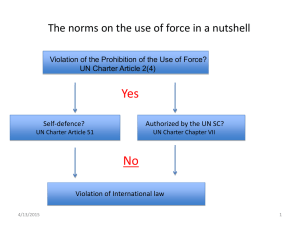

Current Legal Issues: the use of force in international law

advertisement

Anticipatory self-defence Current Legal Issues: the use of force in international law Dr Myra Williamson Kuwait International Law School 2012 Reading The background reading for this class is from Shaw, M International Law 6th ed pp1137 – 1140 • You already have this material – you would have photocopied this at the beginning of the semester • Please read this (and the footnotes, if you can) before class or at least by the end of the lectures on this topic • In addition, please check this summary on wikipedia for further information: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Preemptive_war What is “anticipatory self-defence”? This is a term used in international law which means using force BEFORE an attack has taken place To “anticipate” means to act first, before the event occurs In this context, it means attacking the enemy first, before they attack you (“darbah istibaqia”?) Why would this happen? If a state fears it will be attacked, it uses force first – it’s like “striking first” to prevent the attack from happening For example, if state A is afraid of state B, and thinks state B will attack it in the future (mustakbal), state A might attack first. This would be an example of ‘anticipatory self-defence’ if state A acted to prevent an attack from state B What does the law say? Article 51 states that: Nothing in the UN Charter impairs (damages) a state’s inherent right to use force in self-defence IF an armed attack occurs… What does this mean? It seems to mean that there must be an armed attack BEFORE a response can be made by the state in self-defence The word “if” is like a condition “If” an armed attack occurs, then the state can use force So if an armed attack has not yet occurred, the state cannot use force Art 51, read literally “(harfian”?) seems to say that there is no right of anticipatory self-defence – there must be an armed attack first, states can’t attack first Conflicting views Scholars of international law don’t agree in this area: Some say that Article 51 requires an armed attack to occur first. Therefore, there is no right of anticipatory self-defence at all (see Dinstein, Brownlie) Others say that because of the word “inherent”, we must look at pre-Charter law. Pre-Charter law did allow anticipatory selfdefence and that survived after the UN Charter was enacted What was the pre-Charter rule? Grotius The Caroline case Hugo Grotius on pre-emptive war We looked at Grotius earlier He wrote a famous book – On the Laws of War and Peace in 1623-24 It contains many of the fundamental rules of international law as they were understood in the pre-Charter era On anticipatory or pre-emptive self-defence he wrote that the danger must be imminent: “…The danger…must be immediate and imminent in point of time. But those who accept fear of any sort as justifying anticipatory slaying are themselves greatly deceived…” The Caroline case (again!) Remember the facts about the Caroline? The British set the boat on fire and sent it over Niagra Falls, killing two Americans There was an exchange of diplomatic letters between Webster (US) and Ashburton (UK) There was also a court case The British were trying to prevent future attacks from the Canadian rebels who were using this boat It was agreed that if it is necessary to use force, because the threat is “instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means and no moment for deliberation” then it is allowed to strike first It was held that the UK could have expected further attacks They were entitled to use force, subject to the conditions of necessity and proportionality So, before the Charter it was ok? Yes, most scholars agree that before the UN Charter came along, states had the right under customary international law to use force before an actual attack had occurred Then the question is: what happened to that right after 1945 when the UN Charter was enacted? Did that right continue or did it disappear? This is mainly what scholars argue about in this area What do you think? By using the words “nothing in the charter impairs the inherent right of self-defence….”, did the framers of the Charter want to preserve something that already existed?? “The nature of conflict has changed” argument Some scholars argue that conflict is different these days The UN Charter is from 1945 – when states fought each other states These days, conflict is different: States can’t wait for the attack - existential threats exist (eg nuclear weapons) Terrorists and other non-state actors can strike quickly, without warning The argument is: conflict has changed so the UN Charter should be interpreted to take that change into account. Therefore, anticipatory self-defence should be allowed under either Article 51 or under the customary law right The ICJ – what has it said? The ICJ hasn’t made a clear and definitive statement in whether anticipatory self-defence is permitted under international law In the Nicaragua case, the ICJ didn’t have to make a decision on this issue The ICJ did say that “self-defence would warrant only measures which are proportional to the armed attack and necessary to respond to it, a rule well established in customary international law” - but no ruling on anticipatory self-defence However, Judge Schwebel, in a dissenting opinion, expressed support for it – he said he wouldn’t want Article 51 interpreted as meaning “if, and only if, an armed attack occurs” So far, the ICJ has never made a clear statement on whether anticipatory self-defence is permitted What about state practice? States have generally rejected anticipatory self-defence. Examples: 1957 Suez crisis UN General Assembly resolution voted (64 votes in favour, 5 against, 6 abstentions) for Israel, UK & France to withdraw their forces 1962 Cuban missile crisis US did not rely on Art 51 – it accepted it could not use Art 51 to justify its naval blockade of Cuba because there had been no armed attack by Cuba 1981 Israeli attack on Iraq’s nuclear reactor (see next slide…) Israel’s attack on Iraq’s nuclear reactor in 1981 (called Operation Opera) On 7 June 1981, the Israeli Air Force attacked an Iraqi nuclear reactor called “Osirak” or Tammuz-I which was still under construction Israel’s attack on Iraq’s nuclear reactor in 1981 Israel reported its actions to the UN Security Council after the attack. Israel relied solely on anticipatory self-defence – there had been no attack on Israel from Iraq The Israeli representative to the UN claimed that Art 51 allowed states to use force in anticipatory self-defence All members of the Security Council rejected this interpretation of Article 51, including the US UNSC Resolution 487 (1981): it strongly condemned Israel’s military attack which was in clear violation of the Charter This resolution is available on my website: please read it This incident showed that most member states rejected the idea that a state can use force BEFORE an actual armed attack has occurred Israel’s attack on Iraq’s nuclear reactor in 1981 This image shows the Osirak reactor after Israel’s attack Recent developments More recently, there seems to have been a change in the position of some states For example, the US: it condemned the Israeli attack on Iraq in 1981….but look at its understanding of ‘self-defence’ in the Bush Administration’s 2002 National Security Strategy: “While the United States will constantly strive to enlist the support of the international community, we will not hesitate to act alone, if necessary, to exercise our right of self-defence by acting pre-emptively against such terrorsits to prevent them from doing harm against our people and our country…” The so-called “Bush doctrine” – named after then US President George E. Bush says that states can use force before an attack occurs, and even before an attack is imminent Aside from the US… In 2002, Australia expressed its support for the Bush doctrine, stating that there should be a new doctrine of pre-emptive action to avert a threat But the UK disagreed – the UK Attorney-General, Lord Goldsmith, said that international law does not permit a state to use force in preemptive self-defence unless the attack is imminent NZ agreed with the UK So, most states did not support expanding the right of self-defence Most states agreed that Article 51 requires an armed attack to have occurred or to be imminent and there be no other way to stop it Weapons of mass destruction Are weapons of mass destruction a special type of threat which justifies using force BEFORE an actual armed attack has occurred? In 2002, the US argued “yes”: The US said that the US must be able to stop “rogue states and terrorists BEFORE they are able to threaten or use weapons of mass destruction against the US, our allies and friends…we cannot let our enemies strike first…” If WMD are an excuse for using force BEFORE and armed attack has happened, wouldn’t that mean that all states which have WMD are legitimate targets for pre-emptive strikes?? What’s the current position in international law? It’s hard to say! Scholars disagree, states disagree, the ICJ hasn’t made a clear statement The prevailing (most popular) interpretation is that states do not have to wait until another state has attacked They can use force if the attack is imminent (ie very close, about to happen, and there are no other ways to prevent the attack) In the Report of the UN High Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change (A/59/565, 2004) the UN said that “a threatened state, according to long-established international law, can take military action as long as the threatened attack is imminent, no other means would deflect it and the action is proportionate” Conclusion This is an evolving area of international law – it is not settled Even if a state breaks the rule in Article 51, what will happen? Israel broke the law in 1981, they were told to pay compensation, they never did. Iraq is still trying to get compensation from Israel. Of course, a state can always seek Security Council approval for using pre-emptive force against another state (noting the problems with the veto powers of the P5 and the political nature of the SC) To the future: What about Iran? Some states are threatening a pre-emptive strike, eg, see Netanyahu’s speech to the UN General Assembly, 67th session, in September 2012, asking when it will be too late to strike Iran Should Article 51 be changed? What would be the consequences? Would states act any differently to they do now? Further reading There is a lot of academic writing in this area For example: Grieg, D. “Self-Defence and the Security Council: What Does Article 51 Require?” 40 [1991] International and Comparative Law Quarterly 366. Mulcahy, J. and Mahony, C., “Anticipatory Self-Defence: A Discussion of the International Law” 2 [2006] Hanse Law Review 231