The Case of Moral Hazard

advertisement

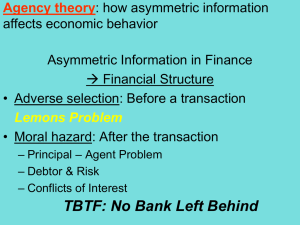

Mainstream Economics and Social Transformation: The Case of Moral Hazard John Latsis, Universities of Reading and Oxford Constantinos Repapis, University of Oxford Structure of the argument i. The role of models in social transformation A gap in the economic ontology literature ii. The role of models in modern mainstream economics iii. Models as representations vs. models as interventions Three epistemic features of models iv. The case of moral hazard One analytical finding, three policy interventions What is an economic model? No widespread agreement: ”… models can be understood as complex objects constructed out of many resources that defy simple description" (Morgan 2008: 1) Yet they define the discipline, the profession and justify imperialism (Fine and Milonakis 2009) How do we explain this tension between centrality and ambiguity of models? Functions of economic models Literature says that models are deductive & mathematical in structure (Lawson, 1997, 2003) However, not all maths is an economic model, so we distinguish them by functional role (Morgan 2008): Fitting theories to the world Theorising As instruments of investigation Representing and intervening "A 'theory' is not a collection of assertions about the behaviour of the actual economy but rather an explicit set of instructions for building a parallel or analogue system - a mechanical, imitation economy. A 'good' model, from this point of view, will not be exactly more 'real' than a poor one, but will provide better imitations." (Lucas 1980: 697) Continued Traditional debates focus on the limitations of models as representations The link to reality is broken, but this does not mean that models are irrelevant: they affect actual social processes We can therefore see models as interventions in the social world Interventions • As they distance themselves from their representative role models have become more detachable from theory and malleable to circumstance • Noticed in HET and Econ Soc, but not approached in a theoretical manner • Our emphasis is on 3 epistemic features of models: specificity, portability, formal precision Defining moral hazard In economic terms, moral hazard is seen as a problem of incentives between a principal and an agent Concept borrowed from insurance Moral hazard vs. morale hazard “… the increase in probability of loss associated which results from evil tendencies in the character of the insured person…” ”…results from the insured person's careless attitude towards the occurrence of losses."(Rowell & Connelly 2012) Applying moral hazard 1 Workers’ compensation schemes (Dembe and Boden 2000) Injuries seen as part of a strategic game between employees (agents) and employers (principals) Reduces worker environment to specific incentive problem Excludes complex relations between agents and environment (social and psychological) Leads to one-sided policy interventions Applying moral hazard 2 The 2008 banking crisis (Dow 2010) The belief that commercial banks are too big to fail led bankers to increase risk and overextend lending, believing that national governments will have to bail them out Reduces relations between client, bank and CB into an incentive problem Denies the role of trust in underpinning the banking system Applying moral hazard 3 Models of moral hazard in a monetary union (Persson & Tabellini 1996) The model assumes that actual institutional arrangements can be reduced to the incentive structures they create for the relevant agents in a moral hazard setting Extended to policy advice in Eurozone sovereign debt crisis (Muellbauer 2012) Conclusions Does the use of MH in these instances display the 3 features discussed earlier? MH was detached from insurance literature and transformed into a incentives problem of determinate form, displaying specificity The combination of the 3 studies show clearly that it is a remarkably portable concept In all three cases the formal precision of the economic approach to MH has crowded out competing explanations from other social science perspectives