Bankruptcy Reorganizations and the Troubling Legacy of

advertisement

Bankruptcy Reorganizations and

the Troubling Legacy of Chrysler

and GM

BY RALPH BRUBAKER & CHARLES J. TABB

2010 U. ILLINOIS L. REVIEW 1375

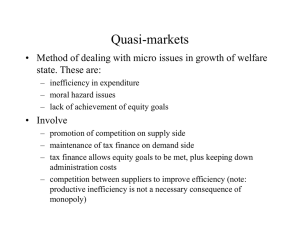

Or, “how scary is the § 363 revolution?”

§ 363

Or, “what is the essence of ‘reorganization’?”

“Reorganization” = ???

Sea change: Plan

363 sale

Chrysler & GM cases are the poster children

highlighting the sea change in recent years from the

traditional Chapter 11 reorganization model of a duly

confirmed “plan” to an all-asset sale under § 363

Plan

363

sale

The cases

Chrysler:

went through bankruptcy in 41 days

$2 billion “sale” from “Old Chrysler” to “New Chrysler” free &

clear of underwater senior secured debt

GM:

went through bankruptcy in 39 days

Credit bid “sale” from “Old GM” to “New GM,” to underwater

secured lenders

Traditional points of controversy re 363 sales

1st: all-asset sale under 363, rather than via plan,

deprives economic stakeholders of procedural &

substantive protections in plan process

2nd: not really a “sale” at all

But a “reorganization” wolf

masquerading in “sale”

sheep’s clothing

“Sub Rosa” plan

Historic “tests” to ferret out the twin concerns

The “sales are suspect” issue:

“good

business reason” (Lionel)

i.e., why can’t we wait for a plan?

The reorganization wolf / sales sheep issue:

No

“sub rosa plans” in a sale (Braniff)

What is not the problem

Neither the “sales are suspect” nor the “wolf/sheep sub

rosa” issue is real concern raised by auto cases

Although the “sub rosa” plan issue, properly understood, is

implicated

Problem: the “plan” / “sale” dichotomy is a false one

almost any sale can be effectuated as a plan, and any plan

can be structured as a sale

So not helpful for a court to seek guidance on whether to approve a

363 sale in a model of a “true” sale or plan – no such thing!

What is the problem

So what is our worry?

Boyd risen from the dead

Boyd

* referring of course to the 1913

Supreme Court ruling in equity receivership case

that any “value” in the debtor had to be distributed

in accordance with distributional entitlements,

notwithstanding a supposed “sale” structure

And yet this is precisely what the auto cases – and

especially GM – appear to allow

Boyd resurrected – and no one noticed

It is bad enough that the reorganization fallacy that

the Supreme Court laid to rest in Boyd was

resurrected in the auto cases

Even more disturbing is that no one seemed to notice

– it happened sub silentio

Which makes it even more likely that reorganization

lawyers will be able to circumvent distributional

entitlements via a 363 “sale”

Without the real issue even being on the table

The central point

“Whether reorganization

value is captured by

“sale” or by “plan” is not the central question, as

long as the means chosen preserves and

upholds chapter 11’s distributional norms”

…

Thus, “courts confronting these issues must keep

their primary focus on the core need to protect the

normative distributional entitlements of

stakeholders, whether the reorganization proceeds

by sale or plan” (p. 1379)

A nod to plans?

Given that central thesis, I might be willing

(probably more willing than my coauthor Ralph?) to

acknowledge that IF distributional issues are

implicated, then a plan may be favored

my basic point is that the plan process makes it easier for the

court to monitor the fairness of, and for affected parties to

have a meaningful say in, the question of “who gets what”

But it COULD be done via a sale as long as court was alert to

need to enforce distributional norms

Our Grades: Chrysler & GM on the real issue

Chrysler:

passed -- did not contravene

stakeholders’ distributional

entitlements

GM:

failed – did violate the rights

of stakeholders to share in

value of entity according to

distributional norms

Acknowledge that our view (esp. on Chrysler) is

controversial (but of course correct!)

Chrysler sale

All assets

35% Fiat

[Old]

8% US

$2B + debt assumption

2% Canada

55% equity +

Senior Secured

VEBA ($10B

$4.6B)

(owed $6.9B)

Trade ($5.3B)

Warranty, dealer ($4B)

Pension ($3.5B)

New

Chrsyler

OUT: Jr. secured; Unassumed unsecured; Old equity

GM sale

All assets

[Old]

New GM

Credit bid

+ pref + $6.7 B

60.8% US

11.7% Canada

+ 10% common stock

+ pref + $1.3B

+ debt assumption

[eg, warranty, product liability, non-govt secured]

US & Canada secured (~ $50B)

Unsecured ($117B)

- Bonds ($27B)

- UAW trust ($21B)

10% Old GM + warrants

17.5% VEBA + warrants

+ pref + $6.5B

1st principles of reorganization

Two distinct issues raised in reorganizations, and

implicated in the whole 363 sale debate:

1st: how much?

2nd: to whom?

One of the problems muddying the whole 363 debate is

that the two issues tend to get conflated

the “sub rosa” plan issue gets confused with the

preliminary question of when an all-asset 363 sale should

be permitted at all

All cash

Way to keep the two issues distinct is to posit an all

cash 363 sale

In effect just converting estate assets into a pot of $

Before sale

after sale

1stprinciple: maximize value

One of the core concerns in a bankruptcy

reorganization is to maximize estate value

This is a question simply of how BIG a pot of $ we

can get

It is in everyone’s interests to get a bigger pot of $

Which prefer?

Sale v. plan agnostic on pie size!

This crucial threshold issue of maximizing estate

value is NOT really implicated in the “sale v. plan”

debate

Value max?

No reason can’t get just as big (or bigger!) a pie out of

estate assets in a 363 sale as in a plan

Sending out disclosure statements, voting, etc. does not grow the

value of the estate

Individual stakeholders don’t enjoy unique & special value

maximization insights that can only be captured via the plan direct

democracy process

Indeed, give much deference to firm in business decisions

Only concern should be, is the pot of $ as

big as it can be?

Aggregate vs individual

Note, though, that just because the action proposed

may maximize the AGGREGATE value of the estate

does not always mean that the value to each

INDIVIDUAL stakeholder will be maximized

So do possibly disadvantage some individual stakeholders if

we partially disenfranchise them via a sale process, rather than

giving them a direct vote under a plan

But, is such a “harm” worthy of protection, if may

make the entire pot smaller?

Answer: “no”

Big pot ≠ who gets

The question of, “is this as big was we can make the

pot of $ ?” is totally distinct from the question of

“who gets what out of the pot”

We should worry more if the “who gets what” issue is

decided via a sale

OK sale

not OK sale

Reorganization premise -> capture surplus

The whole point of trying to salvage a firm via a

bankruptcy reorganization – rather than just

liquidating the firm (in or out of bankruptcy) -- is the

belief that extra value (the “going concern surplus”)

can be captured

going concern surplus

liquidate

reorganize

363 Sale may be ok if get surplus

In principle, if our 1st driving concern is to make sure

we capture the “surplus” for the benefit of the

stakeholders of the firm (viewed in the aggregate),

then we should not necessarily object if we can

realize that surplus via a 363 sale

363 sale? If realize ->

then

Judicial test

In theory, then, a 363 sale should be fine if the only

issue is whether that sale allows us to maximize

aggregate estate value

i.e., are we still capturing the surplus?

OR

Judicial test: “good business reason” for 363 sale

Gets at the “getting the surplus?” issue, but indirectly

The “lose-by-waiting” OK for sale

Could just ask directly in any 363 all-asset sale:

“does this maximize the estate value?”

Instead, the Lionel “good business reason” test is

framed on a “would we lose estate value if we waited

for a plan?” and then only approve if answer “yes”:

Sale now =

Wait for plan =

Why require “lose-if-wait” justification?

Query why courts will only approve an immediate 363

all-asset sale if evident would lose $ by waiting?

Deference to the plan process protections (e.g.,

disclosure, voting, etc.)

As contrasted with the more limited process rights in a sale (notice,

opportunity to be heard, etc.)

But do these really matter on the question of how to

maximize estate value?

Plan dissent usually is over the “who gets what” issue, not over the

“what should we do with the assets” question

Could change test

Could change the test to ask only if the sale = max

Even if would not lose anything by waiting

Thus, argue no reason not to approve 363 sale if:

Sale now =

Wait for plan =

it’s going to be the same size pot either way!

Applying the “GBR” test in auto cases

Even with quibble about whether it really makes

sense to use a “good business reason” test for a 363

sale, rather than a “is this really the max” test, was

not much of a hurdle for courts to clear on the facts

in either Chrysler or in GM

Courts in both cases saw the estate value as a

“melting ice cube” – i.e., waiting

likely would cause enormous loss

in aggregate value

Call the government’s bluff?

One of main reasons the proverbial “ice cube” would

melt in the auto cases was the risk that the US and

Canadian governments would walk away

They were putting up all the $, and said “sale now or

forget it”

Some critics say should have called their bluff – but

would it really have been worth it? No other deals

were on the horizon

What DO we need a plan for?

If a 363 sale (rather than a plan) may be just as –

indeed if not more – effective in maximizing

aggregate estate value, then one might ask – what

role does a plan ever serve?

The answer is: determining who gets what, i.e.,

making decisions on how to DISTRIBUTE estate

value to the interested stakeholders

Negotiating over the surplus

Premise of the whole plan democracy process is to

ensure a fair method of allocating the supposed

going concern surplus

Surplus: to whom?

Plan may be required

Liquidation baseline ->

Informed suffrage on “who gets what”

Idea is that the various stakeholders should have the

right to negotiate over, be informed about, and have

a formal say (via a vote) as to which of them gets

what share of the reorganization surplus, all subject

to baseline protective allocation rules

And that is what we call a “plan”

Sale problems

If try to allocate reorganization value under a 363

sale, lose both (i) process and (ii) substantive

protections

Process: disclosure, voting, etc

Cannot really substitute fully for in “sale” under 363. Fatal?

Substantive: best interests, absolute priority, etc.

Court COULD invoke these norms in deciding whether to

approve a 363 sale

When 363 “sale” is not OK?

363 “sale” usually should NOT be approved when

that “sale” directs the distribution of the sale

proceeds among various stakeholders

Group A

50%

Group C

Group B

Or, at least import distributional norms

As 2nd-best option, if otherwise a quick “sale” does

seem necessary (due to exigencies, e.g., auto cases)

the court at the very least should import

distributional norms from the plan confirmation

rules, including:

Best interests test

Fair and equitable

No unfair discrimination

Class treatment

Plan

rules

363

sale

“Sub rosa” plan issue

This “distribution-by-sale” problem parades under

the rubric of “no sub rosa plans in a 363 sale”

We don’t think the use of the “sub rosa” terminology

moves the analytical ball forward –begs questions of

“what is a sub rosa plan, and why is that bad?”

better

And

to focus directly on what the real concern is

that concern is allowing unchecked & unmonitored

distribution to stakeholders contrary to rights

Chrysler distributional attacks

(1) Indiana Pension Funds (a secured Cr) argued sale

was an invalid “sub rosa” plan because it gave

“value to unsecured creditors (i.e., in the form of

the ownership interest in New Chrysler

provided to the union benefit funds) without

paying off secured debt in full.”

(2) Unequal treatment of unsecured creditors ->

through the debt assumption of some unsecured

claims, but not others

Reprise: Chrysler sale

All assets

[Old]

New

Chrsyler

$2B + debt assumption

35% Fiat

8% US

2% Canada

55% equity

Senior Secured

(owed $6.9B)

VEBA ($10B

+ 4.6B)

Trade ($5.3B)

Warranty, dealer ($4B)

Pension ($3.5B)

OUT: Jr. secured; Unassumed unsecured; Old equity

Secured Cr objection? nay

Indiana Pension Funds’ objection to the distribution

to the VEBA was properly rejected by Judge

Gonzalez – no distributional violation in the sale

1st: IPF’s class consented to the give-up

2nd: even if class had not consented, the “fair and

equitable” protection for a secured class is not

through absolute priority rule (i.e., cut out jr classes),

but through sale of collateral with credit bid right

The consent?

One main argument that has been leveled agst the

“consent” point is that secured CR consent was

tainted by conflict of interest, b/c the US govt was

dangling TARP $ out to those banks, and effectively

forced them to “consent” to Chrysler deal as a

condition of getting the TARP $:

just say “yes”

Sale / plan -> no difference re consent

1st problem with the “tainted consent” argument is

that Judge Gonzalez found no factual evidence to

support it

2nd, and more fundamentally – no reason why judge

would have made a different finding on legitimacy of

consent if in a plan context

Would challenge to “designate” in a plan

But same factual decision as in sale setting

Purely a judicial call – parties don’t “vote” on consent!

Protect Secured via Credit Bid

For class of secured claims, a primary “fair and

equitable” distributional protection is the right of

secured class to CREDIT BID their claim on a sale

In Chrysler:

sale price = $2 billion

Secured class had claim of $6.9 billion, secured by all assets

If thought $2 billion not enough, senior secured class could

have “credit bid” up to $6.9 billion and acquired all assets of

Old Chrysler

Did not do so – suggests ok with $2 billion price tag

{bracket caveat: Philly Newspapers!}

Won’t dwell on it here, but of course you all know of

the possible problem wherein secured creditors are

denied the right to credit bid in a chapter 11 sale, see,

e.g., Philly Newspapers and Pacific Lumber

Of course, even there the secured Cr is protected by

an “indubitable equivalent” standard, so could be OK

if bankruptcy judge does her job right

Bigger problem: CR inequality in debt assumption?

Have been considering the distribution-by-sale issue

on premise that have a cash-only sale

And suggest there is usually little to worry about there

But what if the sale instead is not all cash, but is for

cash PLUS assumption of some debts?

risk inequality

The sale purchaser’s assumption of some unsecured

debts, and not others, raises serious risk of improper

distribution-by-sale

Some unsecured creditors (those whose debts are

assumed) do better than others (those whose aren’t)

And occurs as a consequence of the sale itself

The distributional norm implicated

Unsecured creditor equality

Implement in plan context through rules governing:

Classification (substantially similar only)

Same treatment in class

Class voting

No

“unfair discrimination” if in cramdown

Unequal distribution?

What about this all-cash sale? NOT approve

Obviously group B gets more than C, which gets

more than A

100

Unsecured

class A

sale

proceeds

Unsecured

class B

50

Unsecured

class C

Can reach same result via debt assumption

Could restructure sale to reach the same result, with

equal distribution of sale proceeds to the unsecured

classes, but with a differential debt assumption by

the purchaser of the to-be-preferred classes

60

Unsecured

class A

sale

proceeds

+ Assume zero

Unsecured

class B

20

Unsecured

class C

+ Assume 30

+ Assume 10

Economically equivalent

The two structures just described are economically

identical in substance:

Purchaser commits to pay 100

1. All-cash: pay 100

2. Cash + assumption: pay 60, assume 40 = 100

Creditor benefits total 100, differentially; same totals

1. All-cash: pay A 20, B 50, C 30

2. Cash + assumption: pay A 20; pay B 20+ assume 30 = 50; pay C

20 + assume 10 = 30

Is differential debt assumption in sale ok or not?

At first blush, one is tempted to (and indeed

probably should) say “of course it is not okay”

As a form / substance matter, should treat as same

case (viz., unfair discrimination as between same

status unsecured creditors) whether done by all-cash

sale or by cash-plus-assumption structure

In a plan, the classes discriminated against could

vote for plan (assume meet best interests test), but

can’t vote on sale so can’t consent to discrimination

When might be ok …

However, in one factual situation, the (i) all-cash and

the (ii) cash-plus-assumption scenarios are NOT

identical

That is when the Purchaser would not pay more --

even if debt assumption were not allowed

E.g., in the Hypo -> Purchaser still will only pay $60 for the

estate assets, NO MATTER WHAT – whether or not allowed to

assume debts

In article, this is what we call “Scenario One” (p. 1396)

debt assumption $ not available to all creditors?

Necessary factual premise, then, is that the $

represented by the debt assumption (in hypo the

extra $40) is NOT $ that the Purchaser ever would

pay as part of the sale price in an all-cash sale

Stated otherwise – if Purchaser WOULD pay the

extra $ as part of cash sale price (in hypo, pay $100,

not $60) if debt assumption not allowed, then court

should NOT allow the debt assumption

We call this a “Scenario Two” (p. 1396 & ff.)

Evidentiary problem

The theory is easy enough to grasp

The problem for bankruptcy judges is the factual

one of deciding whether a case is a permissible

Scenario One (where Purchaser really, truly, won’t

pay more) or a verböten Scenario Two (where

Purchaser would in fact pay the debt assumption $

as part of the cash purchase price)

Impenetrable inquiry into “WWPD”

A major proof difficulty is the impenetrability of the

factual inquiry into the question of “What Would

Purchaser Do” if debt assumption were not allowed

Self-serving testimony by Purchaser

High risk of collusion

And Purchaser may be completely indifferent to form

Analogous to other preferential give-ups

The sort of problem encountered here is very similar

conceptually to other preferential treatment

situations, such as “critical vendor” payments or

preferential lending terms (such as crosscollateralization)

There I have suggested that only way to be sure is a

OK Scenario One is to never approve a possible

Scenario Two!

i.e., have a flat prohibitory rule

Purchaser could still pay later

If have a flat prohibitory rule against a debt

assumption as part of a 363 sale, does not preclude

the Purchaser from paying off the “critical” parties

AFTER the sale occurs

In Hypo – Purchaser pay $60 in sale, distribute $20

each to classes A, B, and C; then, after sale,

Purchaser can assume $30 of B’s debt and $10 of C’s

debt, if so wishes

But Chrysler still OK

Having said that a flat prohibitory rule has much to

recommend it, we still conclude that the Chrysler

debt assumption = legal Scenario One

As Judge Gonzalez said:

“not one penny of value of the Debtors’ assets is going to

anyone other than the First-Lien Lenders”

“any of the obligations … do not constitute a distribution of

proceeds from the Debtors’ estates”

Why Chrysler OK?

Chrysler is perhaps the one factual situation where

we CAN verify the factual claim that the Purchaser

would not pay more. Why?

Because the First-Lien Lenders had every incentive

to get every additional dime from Purchaser that

Purchaser would pay, b/c it all was going to them

Paid $2 billion, owed $6.9 billion

And could credit bid up to $6.9 if did not like the $2 billion

price tag

Evidence that purchaser really means it

Thus, in Chrysler, the fact the senior lenders went

along with sale structured as $2 billion + debt

assumption is strong evidence that “the entirety of

the debt assumption … was incremental value that

the government was willing to pay only in the form

of debt assumption.” (p. 1399)

* of course, one could resurrect the “coercion” claim re TARP

funds, but that is a distinct factual question

Bottom line Chrysler

Not a prohibited sub rosa plan

“The sale itself does not dictate distribution of sale

proceeds in a manner that set aside the Code’s rules

about priority and distribution”

“Furthermore, the dynamics of the Chrysler sale

were such as to give considerable comfort as to the

verifiability of that central fact, which is almost

equally as important”

GM: ritualistic self-sale = “reorganization”

On the crucial sale-approval issue of whether the sale

dictates distribution in a manner that sets aside the

Code’s rules about priority and distribution (and on

whether that fact is verifiable), we gave Chrysler a

(somewhat surprising) thumbs-up

But GM is, as we say, a “horse of a different color, on

both counts”

the GM “sale” = “reorganization” horse

GM not a cash sale

“Through a credit bid of secured debt, substantially

all of GM’s assets were transferred to a newly formed

acquisition entity whose new capital structure had

already been divvied up amongst GM’s creditors”

“with a much larger allocation … to UAW retirees

than to GM’s other unsecured creditors”

Reprise, GM sale

All assets

[Old]

New GM

Credit bid

+ pref + $6.7 B

60.8% US

11.7% Canada

+ 10% common stock

+ pref + $1.3B

+ debt assumption

[eg, warranty, product liability, non-govt secured]

US & Canada secured (~ $50B)

Unsecured ($117B)

- Bonds ($27B)

- UAW trust ($21B)

10% Old GM + warrants

17.5% VEBA + warrants

+ pref + $6.5B

Time machine: back to equity receiverships

“equity receiverships” developed in 19th century to

save insolvent railroads

Keep the road running

Readjust the debt structure

GM is a “back to the future” resurrection of the form

of equity receiverships – but without

the protective rules designed to

safeguard normative entitlements!

A “real” sale

Hypo: Borrow from Boyd

Assets

{free & clear}

Debtor

1. Mortgagees $157M

2. Unsecured Creditors

(Boyd)

3. Stockholders

Actual sale

$61M cash

Purchaser

The equity receivership structure: “self-sale”

Northern Pac. Ry. Co. v. Boyd, 228U.S. 482 (1913)

Assets

{free & clear}

DR: N. Pac.

Railroad

1. Mortgagees $157M

2. Unsecured Creditors

(Boyd)

3. Stockholders

Judicial sale

$61M bid

Purchaser: N. Pac.

Railway

1. Old Mortgagees

2. Unsecured Creditors

(Boyd)

3. Old Stockholders

Boyd’s beef

Argued that his claim, ranking with the unsecured

creditor class, had to be paid before the stockholders

could retain an interest in the “new” company

Standard fare that debts have to be repaid before equity

The supposed “sale” was just a sham (and thus void) as to

him – old stakeholders transmuted themselves into the

new stakeholders, while squeezing him out, and leaving

intact those classes senior AND junior to him

Thus he should be able to enforce his unsecured claim

against the “purchaser” (Railroad)

The “no value” argument

Justification proffered was that Boyd was out of the

money anyway, since the 1st-lien mortgages were for

$157M and the sale bid price was only $61M:

“It is insisted, however, that … the specific finding in the

Paton Case, established that the property was worth less

than the encumbrances of $157,000,000, and hence that

Boyd is no worse off than if the sale had been made

without the reorganization agreement. In the last analysis,

this means that he cannot complain if worthless stock in

the new company was given for worthless stock in the old.”

228 U.S. at 507.

What’s it to him? It’s irrelevant, right?

In effect, the argument was that since his unsecured

claim against the debtor was worthless anyway, it

was irrelevant as to him what the Purchaser chose to

do in allocating interests in the new enterprise

WRONG! said Supreme Court in Boyd

In one of the most important decisions, and passages, in the history of

bankruptcy reorganization law, the Supreme Court in Boyd flatly

rejected that argument at 228 U.S. at 508:

“If the value of the road justified the issuance of

stock in exchange for old shares, the creditors

were entitled to the benefit of that value, whether

it was present or prospective, for dividends or

only for purposes of control. In either event it was

a right of property out of which the creditors were

entitled to be paid before the stockholders could

retain it for any purpose whatever.”

Value Debtor’s Estate = New Entity

S. Court’s determination in Boyd turns on what

should have been an obvious truism:

the value of the pre-sale Debtor’s estate is exactly

equal to the value of the post-sale “Purchaser”

DR: N. Pac.

Railroad

=

Purchaser: N. Pac.

Railway

No divvying up in self-sale!

The result of Boyd (and similar cases, see p. 1403) is:

“the

‘purchaser,’ acting under the guise

of a ‘sale’ of the debtor’s property to it,

was not free to dole out interests in the

new ‘purchasing’ entity to the debtor’s

creditors and shareholders in whatever

manner the ‘purchaser’ wanted”

Vertical equity required

Boyd involved a problem of vertical equity

Unsecured creditor (Boyd) has HIGHER priority entitlement

against DR’s estate – and thus against a ‘self-sale’ “purchaser”

-- than do shareholders

Can’t give anything in “purchaser” to the junior class

(shareholders) unless pay higher-ranking class (unsecured

creditors) in full

1. Mortgagees $157M

2. Unsecured Creditors

(Boyd)

3. Stockholders

must respect that order

and Horizontal equity required as well

Court’s reorganization protections applied equally to

horizontal equity

Unsecured creditor has SAME priority entitlement against

Debtor’s estate as do other unsecured creditors

Can’t give MORE to one unsecured CR than another, without a

darned good reason – i.e., no “UNFAIR DISCRIMINATION”

Debtor

Reorganized “Purchaser”

secured

Unsecured A

Unsecured B

equity

secured

Unsecured C

Unsecured B

Unfair discrimination protection

In diagram on preceding slide, Unsecured A and

Unsecured C could rightly complain about fact that

Unsecured B got a stake in the reorganized

purchaser, and they did not

Yet that is precisely what happened in GM: the UAW

retirees – who just had an unsecured claim like many

others -- got a much larger share of “New GM” than

did the other unsecured creditors

{in diagram, then, UAW retirees are Unsecured B}

Not an absolute bar, but …

Note that the “no unfair discrimination” does not

mean that there can never be any “discrimination”

between unsecureds – just that it can’t be “unfair”

So can be justified if PROVE the added value to the

reorganization effort provided by the favored class

And indeed the need to procure the good will of a key union

could be just such a justification

But the plan proponent has to prove it

GM/Chrysler sub silentio “repeal” of Boyd

Now (in the 78th slide), we come – at long, long last – to

the “troubling legacy” of GM & Chrysler, which stems

from those courts’ statement that:

“The allocation of ownership interests in the

new enterprise is irrelevant to the estate’s

economic interests”

And other similar statements, including:

“the purchaser was free to provide ownership

interests in the new entity as it saw fit”

Contradicts Boyd

As showed earlier, in a “self-sale” setting, that exact

argument was directly rejected by the Supreme Court

in Boyd

Immunizes sale allocation of value from scrutiny

If followed, the disturbing consequence of the

GM/Chrysler theory is that ANYTHING GOES in

terms of allocating value in the “new” entity

The allocation of value in the new entity will be

totally immunized from any judicial scrutiny

whatsoever

And the excluded parties don’t even get a vote!

Our take

(p. 1404):

“There are no limits; the § 363 sale

assumes irrefutable and

uncontestable omnipotence.”

And can do it for a “good business reason”!

2nd Circuit in Chrysler misguidedly collapsed and

conflated sub rosa plan distributional concerns into

the more general preliminary inquiry as to whether

can do a 363 sale at all, viz.,

All proponent need show is a “good business reason”

So if debtor has a “melting ice cube” – apparently

cannot only do an all-asset sale now to maximize

value – but can distribute that value among

creditors and stakeholders without any restriction!

Goodbye Boyd!